Talk delivered at Curtocircuito Festival, Santiago de Compostela, October 9, 2014

Question

When I was a young person, like you, I was driven by the need to find the answers. Perhaps it was the taste of an answer, the delicious sweet taste of an answer as it rolled off my lips. I craved this sensation, I needed to feel it over and over. But as I grew older, my taste buds changed, and what I longed for was not an answer, but a question that I could savour. Because when I have an answer, when I’m certain of who you are, then I already know what you’re going to say, then I already know all of the possibilities you hold within your face. When I have the answer I stop seeing you, I only see the answer, in other words I am living in a bubble of me, my truth, my certainty.

In order for us to begin together, I mean, to take the first step, to have a real encounter, in order to take the first shot of my first movie, for instance, a movie of your face, if I want to make a movie of your face, what I need to do before I pick up the camera, is that I have to put down my answers. I need to put down my heavy answers, and instead, become a question. Who are you? Who are we together here today in this moment?

Koans

I find a great comfort in questions. Imagine my surprise when I discovered a storytelling tradition that is also interested in just these kinds of questions. It comes from Japan, where the contact between Buddhism and Japanese culture created what became known as Zen, Zen Buddhism. In Zen culture there are a set of stories that are studied very carefully, with a lot of seriousness and humour. These stories are called koans, and they are part of a koan curriculum. Students work through these stories or koans in sequence, one after another, the same way we might take up a series of great books, or a series of math problems. Sometimes students spend their entire life reading a single story.

I’d like to share with you this very short story, it is part of a collection of koans called the Gateless Gate. There have been hundreds of people, thousands of people, who have dedicated their entire lives to reading and studying this little story. It goes like this.

Wuzu Fayan said, “It is like a water buffalo (an ox) that passes through a window. Its head, horns, and four legs all pass through. Why can’t the tail pass through?”

Each student needs to find their own answer for each koan. Every answer is entirely singular, and it’s not a matter of being clever, or understanding a system and breaking it down, like math. You become the answer with your whole body-mind or you don’t. And after you do, the tradition invites you to write a poem to show your new understanding of the koan.

The 48 stories of the Gateless Gate were gathered up by a guy named Wumen Huikai in twelfth century China. Would you like to hear his poem about this little story? It’s very beautiful. Here is the zen maestro, offering a commentary on Why Can’t the Tail Pass Through? As I read it, I hope you understand that all I am talking about is my practice. All I am talking about, is the way I make films.

If it passes through, it will fall into a ditch;

If it turns back, it will be destroyed.

This tiny little tail –

What a strange and marvelous thing it is!

Attention

I am interested in that part of movies often called fringe or experimental or avant-garde. Watching these sometimes very difficult movies, is another way for me of asking this question: why can’t the tail pass through? For me, the project of fringe movies has to do with attention. How do we pay attention? All those movies, all those hopes and dreams, all those inventions and strategies and wonders, I think it can all be summarized in this single word: attention. In a normal movie if you notice that you’re watching something, it’s failed, because you got off the rollercoaster. But fringe movies are a demonstration of attention. You’re supposed to notice that you’re on a roller coaster. How do we pay attention? How do we notice something?

Operation Cast Lead

On December 27, 2008 the Israeli government began Operation Cast Lead which killed 1800 Palestinians in the Gaza Strip. Sometimes someone so close to you feels far away. And sometimes someone so far away, feels so close, as if they were the real life, and you were the shadow. It was like they were firing on my home and killing my family. So I started making a movie called Lacan Palestine. Lacan is the great French psychoanalytic theorist, and Palestine is the country that isn’t a country. I don’t know how it is here in Spain, but where I’m from, in Canada, it’s very difficult for anyone in the corporate media to write or talk about Palestinians. It’s as if there were an invisible wall of bricks, and glass and hasbara and words, so that when Canadian reporters look in the direction of a Palestinian, their eyes jog right around them. Just a few months ago, I remember the day when a single Israeli man died, and I’m very sorry that he died, and 350 Palestinians were dead. The Canadian reporter announced, 350 Palestinians died, and this man, and they gave his name, and they told us he was giving lunch to the Israeli troops, and that he had a wife and children, they told us where he lived. This was the news. I’m giving you the news. This man was a person while the Palestinians were simply dead. They didn’t have names, they never fell in love, they never wanted to read a book, or hold your hand, or look at your face with longing. They were not quite human.

Mike

So I wanted to make a movie, and as usual, because this is the fringe, this is an experimentalist movie, I would take this very long detour. There’s the straightforward road, and then there’s the wandering journey, where you have to stop along the way and look at: oh the light coming onto that plate of apples in the morning. Incredible. I need these detours, these obstacles, to make my work, they’re the most important thing, without an obstacle, I don’t know how to begin the work of attention. I needed to find a way to make the Palestinians visible again, and in order to do this I needed an obstacle, and the obstacle was my friend Mike. He is a genius, he could recite long passages of James Joyce and Herman Melville and the bible by heart, and he knew everything about Jacques Lacan, to me, he was Jacques Lacan. So I would get him to explain Lacan to me, even though I knew I would never really be able to understand him, and going through this obstacle of my friend, I would find my way to Palestine, Jacques Lacan would take my hand and lead me into Palestine.

One of the most important discoveries I made during this film was about Mike’s face. He has so many faces in his face. He was telling me about his father, and how his father had a heart attack and nearly died, this happened when he was a young boy, only seven or eight, and the doctors tell him that if he behaves badly, if he upsets his father ever again, his dad is going to have a heart attack and die. Wow. Heavy thing to tell a young kid, right? But when Mike tells this story, the words are a description of what happened, but his face is a documentary. The words are a kind of true fiction, but his face shows me what he looked like at that moment when he was seven years old talking to the doctor. The words are a trigger, they become a trap door and Mike steps into them, and voila, he is once again that little boy of seven years old. But only for an instant. For less than a second.

Archive

One of the great pleasures and great difficulties of making movies, is that you always work with an archive. Everyone knows about this today, because our computers have turned all of us into archivists. All of my favourite songs, my texts, my emails, my pictures, they’re all archived on my computer, they’re all dated and labeled. The frantic organization of the archive signals to me that this culture, is a culture that is deeply afraid of losing something, otherwise we wouldn’t have collected an entire culture around this machine that obsessively puts everything in a place where we can find it.

As a movie maker, I have footage, a certain amount of footage, and that is an archive, and I pull moments from this archive and set them into relationship with each other, and always I am looking to see how they can further this project of attention. How can this archive help me, and help the viewers of this movie, pay attention? So I’m watching Mike tell this story about his father, and I’m watching his face, I’m reviewing this small archive of his face, and I notice something, so I plunge into his face, I watch it one frame at a time, there are thirty frames in one second, and then I enter into a subterranean world, an underground world that is in plain sight of everyone here, but nobody sees it. His face becomes everything that he is talking about. His face becomes the past, it is travelling in time, there are so many versions of Mike he is holding inside a single face, and I can extract these faces, so that I can share them with you, by using a series of freeze frames to show the documentary truth of this moment between the two of us. It might look stylized, the pictures no longer flow in real time, instead they are interrupted, they appear epileptic: frozen, moving, frozen, frozen again, frozen again, moving, but there is a truth in that rhythm that is Mike’s truth. If you knew him the way his friends knew him, this wouldn’t be necessary. Because when you’re deeply paying attention to someone, particularly if you can practice the art of not–knowing, then you can be tuned into the most important part of what happens between two people, and that is the art of the invisible. This is what we are practicing with each other all the time. The art of the invisible. The most perfect movies for me, are only about the invisible world. In other words: the tail of the ox. Why can’t the tail pass through? By showing these moments of Mike’s long ago face, I am hoping to share moments of his invisible past that is rising up to the surface for an instant, 1/30th of a second, before it is swallowed up again in the restless flow of the present, where we are busy forgetting everything.

Gift

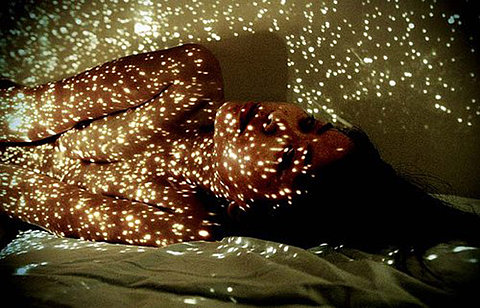

One day my friend Lauren said to me: The greatest gift you can give me, is the gift of your attention. Is that true for you? Can you imagine lying down sick when you’re very old and very close to death. At this moment, your house, your possessions, your awards and achivements, all the things in your life just melt away. They don’t mean much. What is important in this moment, when you can taste the end of everything you’ve ever known, when you can feel down to the end of the exhale? It’s this quality of attention that you can give to someone else. The only thing that is really important, is relationships.

I think that we live in a culture that keeps celebrating people who are a little bit unwell, who feel that they are lacking something, there’s a hole they need to fill, and they’re go to fill that hole by getting attention. We’ve all met people like this, they’re the person at the dinner party who never stops talking. and they can only talk about themselves. When I wait in line at the grocery store I see these shiny magazines with movie stars on the covers, and they’re all busy needing so much attention. These are people who are always taking.

But I think the real heroes of this culture are the ones who know how to listen. This is what I want to see on the covers of those shiny magazines. A picture of someone who is listening. A picture of someone who is able to drop deeply into a place of not-knowing so that they can bear witness to the world as it is. Not to the world as they would prefer it to be, not to a version of the world, but to things as they actually are. To give your attention to this moment, which is the only moment when we can do the work of the cinema, this moment is the only moment when the cinema can appear, and it does so, I believe, whenever we are able to see clearly, without all of our ideas, when we can drop our ideas and appear naked in this moment together and to take the terrible risk of seeing something you can’t understand, that you can’t explain, that you can’t put into words. That you can’t answer. Because as soon as you have the answer, you throw it away, it’s gone. How could you possibly answer, how could you possibly explain a face, a face that you’ve fallen in love with?

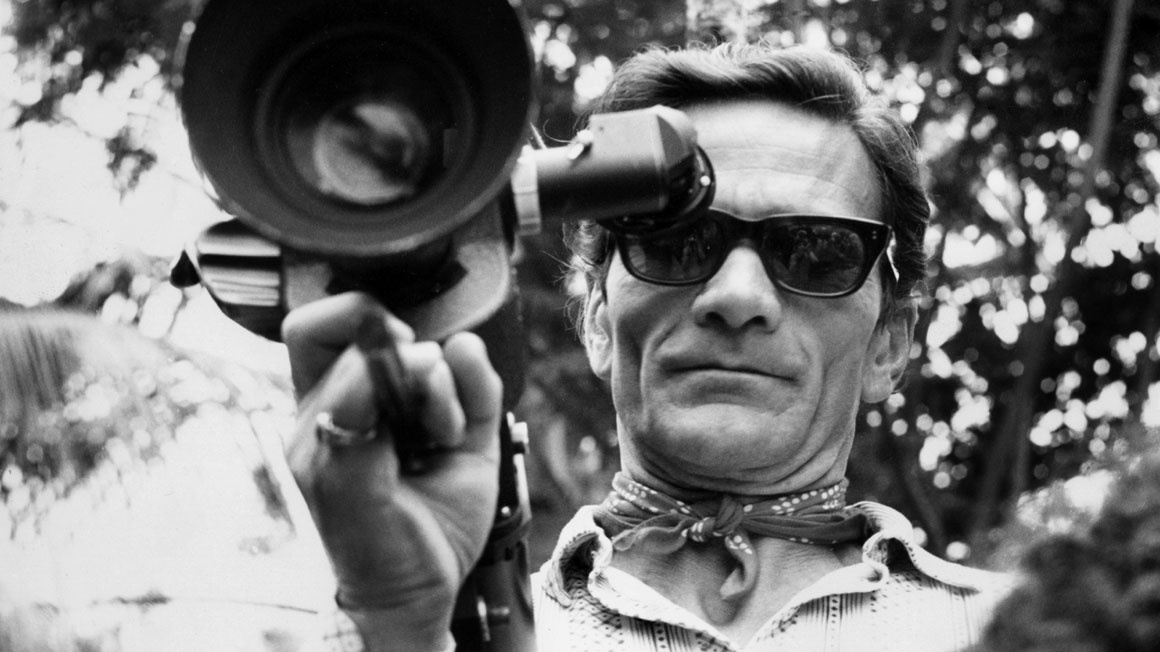

Pasolini

I’d like to share with you some words by Pier Paolo Pasolini, the great Italian poet and filmmaker. Here is a short poem.

I force myself to understand everything

(What is it you need to understand? Oh, everything)

ignorant as I am of any life that isn’t

mine, till, desperate in my nostalgia…

I think he’s telling us: I’m ignorant of any life that isn’t mine, in other words, I’m stuck in my old patterns of seeing and thinking, this is what he calls “my nostalgia” – “desperate in my nostalgia.” Why is he desperate? Because he can feel the bars of his cage. He can feel his restrictions, the restrictions of the old familiar ways, the old comfortable ways that he uses to describe his world. Can you feel your restrictions (I think this is the invitation of this poem)? Can you feel the places in your body where you are tight, gripped, holding on, places in the life of your body, in the life of your city, that you can’t feel? Pasolini says: I need to begin with everything. I have to make sure that I don’t leave anything out. This is how we’re going to begin. This is the first line, this is the first step. And how do I reach this open myself, how do I open the door to let everything come in? I let go, knowing more means knowing less, I let go of my ideas, of my usual patterns, my old certainties. I get lighter. And then he writes about what happens when he looks from this new place of not-knowing.

I realize the full experience

of another life; I’m all compassion

but I wish the road of my love for

this reality would be different, that I

then would love individuals, one by one.

All of a sudden I’m here, and you’re here, and with a camera, with a necessary third element – we have theis-antithesis-synthesis – as Hegel would say it, and that is the cinema. The beginnings of the cinema.

Tail

Wuzu Fayan said, “It is like a water buffalo (an ox) that passes through a window. Its head, horns, and four legs all pass through. Why can’t the tail pass through?”

Common

A water buffalo is a common site in China or India, it’s like a bicycle in Santiago de Compostela or a pick up truck in Madrid. Without a water buffalo you can’t get water, you can’t get around. Perhaps it stands for the utility of the mind. It’s always nearby, always ready to serve if it’s asked in the right way. The water buffalo, like your mind, can be trained in certain ways. Though at some fundamental level it’s unknowable. Sometimes I look at the person who is sleeping beside me and I wonder: what do I really know about you?

In the koan the water buffalo is coming through a window. The large parts make it through — the body and legs — but some small part doesn’t make it. That small part might be called awakening. Waking up to the thing that you’ve spend your entire life avoiding, that you’ve built your entire life trying to avoid. It means having trouble but without defensiveness or inhibition or apathy.

The tail is the one thing we haven’t been able to work with. It’s that little bit of anxiety, the addiction that we can’t turn off or the ideal we can’t embody. We like the idea but maybe we’re not living it.

Thumb

Perhaps the door to this room, is like the window in our story, and perhaps you are the water buffalo. Is there something you’ve left behind when you came in here? One of the newly common features of public life is to do very focused exercises with your thumb. It’s become the most important part of the body. You see people with their thumb exercising machines and they do this: (mime thumbing through a smart phone). Our telephones are one way of not being here, here, in this moment. They’re like a time travel machine, it takes me away so I’m never all here. The smartphone is like the tail of the water buffalo, and it suggests to me something about fear. Why is it so hard to be here? I don’t know about you, but for me it’s because I’m afraid. I’m afraid to tell you what I really think. I’m afraid to show you my real face, my unguarded face. So I’ve brought along my first line of defense, my telephone, and that makes things a little easier.

Fears

Maybe the tail is also our young life, the life that we used to have, that is haunting us. You see this a lot with old bands who are forced to play their old hit songs they wrote when they were twenty years old, and even though they’re written ten songs, a hundred songs since then, we want to hear only the old favourites, the hits. The bands are haunted by their young selves, they live in the shadow of the people they used to be.

M Stone: “Psychologists tell us that our adult life has been sculpted/shaped by our childhood. Freud said that our greatest fear was the fear of dying, and that we repress the fear of death. Adler, who split from Freud, said that what we repress most is power. Jung, who also split with Freud, said that the quality we most repress is a desire to connect with something bigger than oneself. Is that why you come to the cinema? Because you grew tired of the old god and you wanted to reinvent him here, to connect with something larger than yourself? Ernest Jones, another psychologist, said that the thing we most repress is the fear that we won’t have desire, that we won’t allow ourselves to want. Our greatest fear is to love our desire and our passion. Would it be too dangerous, too awful, if you got what you wanted? If you could tell you admit to yourself what you really wanted? Perhaps each of these psychologists with their fear of death, the fear of connecting with something larger, the fear of what we want, they might all be projecting the results of a deep inner searching.”

Against Yourself

You think you’ve got through the window, you think you’ve walked through the door, but then someone offers you a new challenge, something that has been left behind. What happens to hatred if you can’t get it through the window? Perhaps you turn it against yourself. The tail, the part of you that you can’t see, comes back in another form. As self hatred, or self punishment perhaps. Or something you can’t see.

M Stone: “The Dalai Lama first visited the United States in the 1980s. At the end of his teaching period, the young psychologist Jack Kornfield asked him, ‘Is there anything you notice that is unique in the United States?’ The Dalai Lama conferred with his translator and answered, ‘Self judgment – I’ve never encountered this before.’ How can a society that loves the self, that celebrates the self everywhere, hate the self so much? (The second most popular hashtag on Twitter is: me. The first is love.) The tail, the small part of you that can’t get through the door, the tail that holds you back might be self judgment and inadequacy: oh, here’s another reason why I’m not good enough.”

Class War

We’re in the midst of the largest liberation movement in history, which is the liberation of every constraint on the very richest people on earth from making money. We’re creating tremendous inequality because everything can be turned into money. Water can be sold, the earth cracked open and fracked, forests leveled. We are witnessing a class war of rich against poor. The rich have repackaged the liberation movements of blacks, women, animals, queers, in order to free their greed and the flow of capital. We can have free trade but not free people. We are creating a permanent underclass. This feels to me one of the most urgent questions of cinema today, particularly the experimentalist, fringe cinema, or what I like to call: the cinema of attention. How can we use the quality of attention in the service of resistance? How can we open to see each other, how can we share our pictures without turning us into logos and brands, something else that can be bought and sold? How can we practice until we’re not afraid of ourselves any longer? To look at the tail and see your unlived life and not be afraid of it.