download the book for free!

Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada

Publisher: Coach House Books, 2nd edition (Dec 16, 2001)

270 pages

Everybody loves the movies. But a movie about the colour blue, or an isolated mountain range, or a man grown so thin the world floats through his perfect transparency? ‘You know what would be really great – to make a two-hour movie about Taylor Mead’s ass,’ remarked Andy Warhol, the most notorious fringe filmer of them all. Welcome to the strange and wonderful universe of fringe cinema, where the only rules left unbroken are the ones that have been forgotten. Twenty-three interviews with Canada’s finest underdogs lay it all down like a road, ready to take you through the vanishing point of personality.

This new edition includes a foreword by Atom Egoyan, and features never-before-heard raps from Ellie Epp, David Rimmer, Ann Marie Fleming, Anna Gronau, John Kneller, Rick Hancox and Kika Thorne, joining fellow fringers like Mike Snow, Carl Brown, Patricia Gruben, Penelope Buitenhuis, Fumiko Kiyooka, Wrik Mead, Annette Mangaard, Gariné Torossian, Richard Kerr and Mike Cartmell.

Michael Snow: Machines of Cinema

Carl Brown: Painting the Light Fantastic

Patricia Gruben: Sifted Evidence

Barbara Sternberg: Transitions

Al Razutis: Three Decades of Rage

Penelope Buitenhuis: Guns, Girls and Guerillas

Fumiko Kiyooka: The Place with Many Rooms is the Body

Peter Lipskis: I Was a Teenage Personality Crisis!

Wrik Mead: Out of the Closet

Annette Mangaard: Her Soil is Gold

Steve Sanguedolce: Sex, Madness and the Church

Gary Popovich: Lies My Father Told Me

Philip Hoffman: Pictures of Home

Garine Torossian: Girl from Moush

Richard Kerr: Last Days of Living

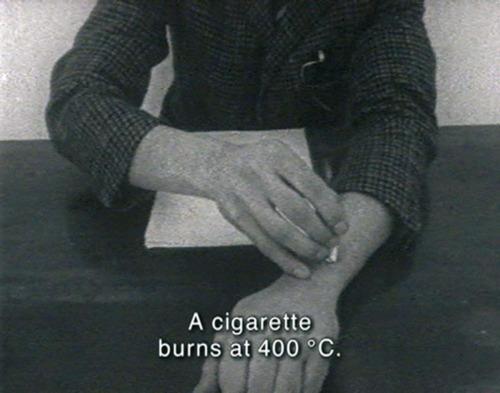

Mike Cartmell: Watching Death at Work

Rick Hancox: There’s a Future in Our Past

Deirdre Logue: Transformer Toy

Ann Marie Fleming: Queen of Disaster

Chris Gallagher: Terminal City

David Rimmer: Fringe Loyalty

Ellie Epp: Notes In Origin

John Kneller: The Church of Film

Anna Gronau: The Dead Are Not Powerless

Kika Thorne: What Is To Be Done?

“In some ways I can’t understand why experimental film continues to have such a small audience,” says celebrated artist and filmmaker Michael Snow in Inside the Pleasure Dome. Perhaps this book by Mike Hoolboom, a veteran of Toronto’s underground film scene, will help rectify matters. In any event, it does much to aid in understanding this underappreciated area of filmmaking, which has an especially rich and vital history in Canada. First published in 1997, Inside the Pleasure Dome is now available in a new and much-expanded edition. As before, the chapters are devoted to long interviews with a wide assortment of filmmakers, all with varied backgrounds, methodologies, and philosophies. Profiles of elder statesmen like Snow (whose ’60s works Wavelength and New York Eye and Ear Control have been massively influential) and Philip Hoffman sit alongside pieces on super-8 maverick Penelope Buitenhuis and idiosyncratic animator Garine Torossian. In his questions, Hoolboom quizzes the filmmakers on technical issues as well as thematic ones—how the work is made is often as important as why. Handcrafted from intentionally weathered scraps of original film and found footage, John Kneller’s stunning films are a case in point. Yet his work is still deemed inaccessible by many and seldom seen. As he ruefully notes to Hoolboom, “It’s funny, people will wait at a bus stop or laundromat but can’t sit through a five-minute experimental film. Sometimes they get so angry.” Regardless of whether it helps decrease hostility toward these filmmakers’ unorthodox visions, Inside the Pleasure Dome provides invaluable insights to the form. –Jason Anderson

“In his latest endeavor filmmaker and critic Mike Hoolboom takes the reader on a splendid tour of “five generations of fringe film in Canada,” i.e.. primarily Toronto and Vancouver. Hoolboom interviews many artists, from Michael Snow as Ur-conceptualist to the anarchistic Penelope Buitenhuis to the process-centered Carl Brown to Wrik Mead with his pixillated gay wit. Barbara Sternberg, Fumiko Kiyooka and Gariné Torossian individually nuance themes of cultural displacement and more. The varied modes of practice that each filmmaker represents are discussed with a surprising, welcomed degree of frankness and articulation… Essential to the cultural surfer for whom moving images should make sense.” (Ger Zielinski, Parachute, Spring 1998)

On Words And Images by Kathleen Pirrie Adams (POV Magazine, Spring/Summer 1998)

“…Fringe Film in Canada is an excellent survey of the issues surrounding the making of experimental film. It provides a sampling of the styles of thought and the creative habits of a handful of artists who represent a cross-section of generations, aesthetic styles and art-making methods. Like any anthology, this one is burdened by the weight of what is missing. What it offers instead of comprehensiveness is the celebration of uniqueness of each approach, each filmwork, each artist. Hoolboom’s quiet assumption that the anecdotal can justify his subject proves good, as the reader becomes immersed in a foraging expedition that uncovers gems like: Carl Brown’s artist as cockroach theory; Gary Popovich’s candid disclosures about how his interest in feminist film theory carried with it a desire for friendship, connection, intimacy; Michael Snow’s story about how in the 1960s the Filmmakers Co-op in New York rented films from their collection to ad agencies wanting to keep up with, and appropriate, the most current stylistic innovations coming up from the underground; or the story about how Man Ray’s sabbatier-style was the result of an assistant flicking the lights of the darkroom on and then off because they were frightened by a mouse.

Part of what makes Hoolboom’s interviews so interesting is their ability to call forth background details that situate and illuminate the films under discussion. The interviews fascinate also because they reveal the very personal investment these artists make, not just in the images they create, but in all aspects of the filmmaking process and the lifestyle of constant experimentation…. Fringe Film in Canada is a collection of conversations concerned with the way the talk that surrounds a film affects it. In the book the world of words and the world of images mesh under a more general rubric: ideas. As Hoolboom says in reference to Patricia Gruben “…a change in ideas might hinge on a change in prose.” It is a book that understands the anti-authoritarian (other) side of the language virus that writers like William Burroughs laboured to confound.”

Sentimental Illness by Hal Niedzviecki (This Magazine Jan/Feb 2002)

“…Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada (Coach House Books) by Mike Hoolboom, recently expanded and re-issued is another largely interview-based oral history of a very specific genre. Though organization here is by artist, the effect is similar. Culture is imbued with history, but not at the expense of its present-day possibilities. I stop to read about how Maritime filmmaker Barbara Sternberg came to make her first film. In one brief section, we get a vision of life in Sackville, New Brunswick in the late 1970s, a sense of an industrial age already drawing to a close, and insight into the mind of a budding filmmaker who would go on to quietly make ten short experimental films over the next twenty years.

Since these texts consist largely of interviews with those who were—and remain—on hand, a living, breathing culture id depicted with all its warts, glories and on-going challenges. They speak of other eras-even idealize them—but in a way that both recognizes the primacy of our current struggles. They are the antithesis of nostalgia, which slaps a beige coating of caricature and conformity over a cultural event—whether the moment ends in a splash of blood or a happily-ever-after-rainbow. Located somewhere between cold hard facts and the soft focus, perpetually re-released hard sell, we find a valid nostalgia that acknowledges the messiness of lived experience without devaluing the lessons—and legends—we might find if we look to the past.”

New Books by Arthur Cantrill (Cantrills Filmnotes, 1989)

Faced with the perennial problem of finding a name for non-mainstream film art, Mike Hoolboom opts for “fringe film,” a gesture I read as deploring its systematic marginalization. Because, as Atom Egoyan puts it in his foreword to this important book: “To treat these films as marginal is to marginalize some integral part of ourselves.” The author sees this book on Canadian work as ‘the child of The Independent Eye,’ a magazine on film art which he brilliantly edited while working at the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre in the late eighties. Both publications were motivated by “the belief that artists should be seen and heard, that they have constructed universes in miniature whose patterns of development possess an exquisite rigour,” and this deserves to be discussed and understood, in the hope of enlarging the public for such work. As a filmmaker and a writer on film, Hoolboom is well acquainted with the problems associated with this project.

The book begins with Michael Snow—who else?—that ‘blue-chip conceptualist’ whose work over so many art media has been impressive. As with other entries in the book, it takes the form of a short introduction, followed by a probing and expansive interview conducted by the author… Perhaps the last interview in the book, Watching Death at Work with Mike Cartmell, goes furthest in mapping out the problems and future of avant-garde film practice. He considers himself to have stopped filmmaking after three films done in the eighties (he has much uncut footage which may or may not form new work), the discussion to do with the future of film seems to be ending in the most pessimistic way, when Cartmell suddenly says, “…it’s astonishing how things change. A stupid invention in someone’s garage can completely change the way everybody things. And there are garages in which the lights are burning all night.”

Filmmaking without narrative by Gale Singer (Globe and Mail)

In an articulate conversation overheard at a café on Toronto’s fashionable College Street, a woman in black mentioned a film she had seen earlier that day. She said, “I loved the riddle of it. I loved not knowing what it (the film) could possibly have meant.” The film she was referring to could only have been an experimental film. Experimental filmmakers seem to throw all caution to the wind. They are able to retain a child-like curiosity about objects, events and processes, which allows them to investigate these without the usual conventions of film construction. They are working without a narrative net. They perceive as legitimate in cinema the kind of exploration many people mistakenly abandon at the end of formal schooling.

I’ve never detected any particular eagerness on the part of experimental filmmakers to clarify what it is they are trying to do, with a couple of notable exceptions. Mike Hoolboom has included these two exceptional filmmakers in this collection of wonderful interviews. Both Philip Hoffman and Patricia Gruben have rendered their exquisite work more meaningful and relevant by constantly engaging in non-obscurantist dialogue about it. Hoffman is a kind of experimental film proselytizer; he seeks out audiences and addresses them in accessible language. Hoolboom has taken his cue from Hoffman, and enriched the potential for understanding this medium—in particular the work of these artists—by engaging in conversations with them that sound as if they were lifted out of the notebook of a wise psychoanalyst. The interviewer asks intelligent questions, but doesn’t impose himself on the subject. There is an implicit trust and freedom between author and interviewee, which releases the words and ideas off the page and into the reader’s imagination.

There may be more experimental filmmakers in Canada than there are people who have ever deliberately seen an experimental film. Most people think that experimental film is Norman MacLaren, and vice-versa. Without quite saying so, it appears that Hoolboom understands this very well. Of experimental filmmakers he says: “I was struck by their incredible perseverance as well as by their willingness to expose themselves to personal risk, ridicule, financial ruin.” He should know. Hoolboom has been part of this avant-garde world for nearly 20 years, as a practitioner and as a kind of dramaturge at the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre, and then as the force behind the now defunct magazine, the Independent Eye.

The first interview is with Michael Snow, probably the person most mentioned by other experimental filmmakers. Experimental film is even more self-referential than other film categories, but if the viewer, or in this case reader, isn’t familiar with Stan Brakhage or Hollis Frampton, these references leave you pretty much in the dark. But Snow is not interested in merely leaving behind a dance card full of names, he has used experimental film to explore or elaborate upon his painting and sculpture. “I got the idea to make a film using Walking Woman … it starts with the figure as an abstract blank, either white or black. It’s a hole in the image in some sense, which later develops to include life through the negative space; that is, real women stood behind the cut-out, and from there it went to these black and white images—it’s a black and white film of black and white people… The end of the film shows a black and white couple in bed.”

In so many of these interviews there is a stream-of-consciousness quality, much like that in certain experimental films. But woven through these dreamy verbal brushstrokes are glimpses of remarkable insight. Patricia Gruben speaks about her film Sifted Evidence , in response to one Hoolboom’s amazing observations. Hoolboom: “He tells her the exact moment he falls in love with her—like the narratives of Christian conversion that obsessively detail the precise moment their life changes forever.” Gruben: “The cliché… maps our sense of ourselves onto our surroundings. But what happens when this sense comes from outside, from a culture that assigns women tools of understanding that don’t necessarily fit with our experience? The woman in Sifted Evidence is caught inside these images; her passivity stems from not being able to work out these contradictions.”

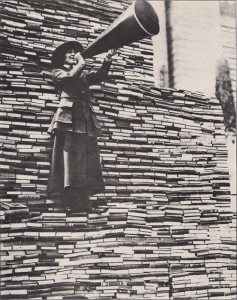

Hoolboom’s intelligence and experience flourish on these pages. The large-format book is rich with photos. There is no index, but each filmmaker’s filmography is included. This is a fine handbook for the interested or uninitiated and the devotee of experimental film alike.

Further Inside the Pleasure Dome by Shannon Brownlee (LIFT Newsletter, July/Aug 2002)

The second edition of Inside the Pleasure Dome takes the reader through the wonderful and curious shutters and gates of the Chinese box that is Canadian experimental film. The collection of interviews, conducted over the course of several years by filmmaker Mike Hoolboom, is by turns personal, theoretical, concrete, aesthetic, psychological and historical. The first edition featured such filmmakers as Michael Snow, Wrik Mead, Steve Sanguedolce, Barbara Sternberg and Philip Hoffman; in the second they are joined by the diverse voices of Rick Hancox, Deirdre Logue, Ann Marie Fleming, Chris Gallagher, David Rimmer, Ellie Epp, John Kneller, Anna Gronau and Kika Thorne.

The book does anything but establish a canon of Canadian experimental filmmakers. As Hoolboom writes in the introduction, those who appear in the book were chosen because their work touched him, and perhaps this is the most meaningful criterion for a collection of thoughts on works that often speak so clearly to the unconscious. It spans the space between the sometimes strange and usually marginal personal experience of making and watching these films, and the community in which they have arisen. Recurring references to such organizations as LIFT, the CFMDC, the NFB and the Canada Council build a sense of shared history. However, these bodies’ histories are always told from the perspective of individuals on the fringe.

Anna Gronau sheds light on diverse moments in the history of Toronto’s avant-garde film community, discussing everything from legal battles over censorship to the difficulties of buying and housing equipment. For today’s community, Kika Thorne’s thoughts on the current political and economic climate contextualize these struggles. The fringe filmmaking community seems to align itself naturally with the left on at least one count: even the most technical or meditatively personal interviews are punctuated by questions of funding and the desire for more general access to equipment.

Of course, the films have not been diminished by the modest means of their creation. On the contrary, the practical limitations have long gone hand in hand with unlimited ingenuity, humour, attention to detail, and both technical and aesthetic mastery. The second edition of Inside the Pleasure Dome sheds new brilliance on that contradiction. Hancox’s commentary of his life and films reads like a wry documentary, and Deirdre Logue’s imaginative and deconstructive self-knowledge casts a direct, intense light on the work. Chris Gallagher, David Rimmer and John Kneller all describe their techniques in such concrete detail that the reader has a sense of being led, frame by frame, through a privileged and uniquely layered screening. Finally, while Ellie Epp speaks powerfully for herself, she also speaks for a way of working on the fringe when she says, “It is amazing to have been able to choose the margins.”

Is this book a set of personal portraits? The interviews are jagged, like sketches of people in action, with none of the false stasis of portraiture. Although at times quite cinematic, the interviews also speak with a personal, experimental art of their own that can only enrich the films and that amorphous, brilliant, seething mass we call experimental cinema.

Diaries of Light: Cara Morton takes you ‘Inside the Pleasure Dome’ (Originally published in LIFT Newsletter, 2001)

“Mike Hoolboom’s book Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada, is a record of unique living moments. Moments through which the filmmakers, as individuals, strive to learn and to explore and to push the boundaries of self and the expression of that self… It’s hard to know whether to be more excited about the book or the work it celebrates. Books and films are so different, yet here in this book, this diary of living moments, we are allowed insight into the very personal nature of filmmaking. The artists collected in this treasury are unique, yet united by the desire to push, to create shifts in perception. They use the medium as a personal tool, to go beyond telling universal stories, to explore the boundaries between the individual, the medium and the audience. Like the films behind the book, the interviews gathered here push beyond the celluloid surface of facts, scripts, stocks, tools, weaving language and personal vision into an inspiring form.

Perhaps the greatest thing about this book is that it provides keys to the mysterious and difficult questions artists are facing today. In the face of cutbacks and financial struggles and a general denial of the connection between art and life, we need places to go when we forget why. We need places where dialogue occurs, where questions are asked, answers sought without expectation of finding them, but there is no giving up. For me, this book has a home beside my diaries. It is a record written in that mysterious yet accessible language of life, providing evidence of those moments when shifts occur. These moments are the history, the life-blood of experimental film, and there they are, dotted like landmarks over the page, for all to experience in their own personal way.”

Inside the Pleasure Dome by William Wees (Canadian Journal of Film Studies Fall 1998)

This large format, well-illustrated collection of interviews with sixteen non-commercial, independent filmmakers offers a revealing cross section of Canadian experimental/avant-garde/fringe film (the filmmakers themselves are far from unanimous as to what label—if any—belongs on their work). Not only do we learn about the lives, opinion and films of the filmmakers interviewed, but we also enter a collective discourse on what it’s like to work on the fringes of critical recognition, public approval and financial rewards.

As a writer and polemicist as well as a filmmaker, Hoolboom has been part of—indeed, has helped shape—that discourse for many years. Someone should have interviewed him for this volume, but at least his questions and occasional comments convey some of his thoughts on the subject of Canadian fringe film. Hoolboom knows the work of each filmmaker well, which not only indicates respect for their accomplishments, but enables him to use his own analysis and interpretation as a way of prompting filmmakers to discuss their films in greater detail. At other times, he simply says, “Tell me about…” (naming a particular film), and lets the filmmaker take it from there. All the filmmakers talk about when and how they got into filmmaking (nearly all of them studied film, to a greater or lesser degree, in college or university—five went to Sheridan College) and Hoolboom leads them through a discussion of their films in chronological order. Consequently, the interviews yield a great deal of useful information about the films and their makers. The result is both an introduction to, and a source for research on, the filmmakers Hoolboom includes in his book.

While comparable in many ways to Scott MacDonald’s A Critical Cinema: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers (three volumes of which have appeared to date), Hoolboom’s Inside the Pleasure Dome is distinguished by its Canadian content and, consequently, by a sense of film “community” working under common constraints and sharing similar concerns. His book, Hoolboom says in his introduction, “takes aim at a single national expression—Canada’s—and provides a sampling of its artists’ voices.” It must be added, however, that Hoolboom’s “Canada” is Toronto and a few points west. More than half the filmmakers live in Toronto (as does Hoolboom) and he includes no representatives of fringe film from the Maritimes.

Nevertheless, there is considerable variety among the filmmakers interviewed. Their inclusion, Hoolboom insists, does not imply that they are the “greatest or grandest of them all.” They were chosen “according to the criteria of individual interest and aesthetic difference,” and they represent, by Hoolboom’s reckoning, “Canada’s five ‘generations’ of film artists.”.. This mix of older, better-known and younger, less well-known film artists implicitly affirms a continuity and renewal within the perpetually endangered species of Canadian experimental film.

One thread running through the interviews is the notion that experimental film is, indeed, endangered, and that the film medium itself is on the verge of extinction. Snow: “It’s going to die. Part of my life’s work is not only decaying, but soon there won’t be any way to show it.” Torossian: “(Film) seems primitive. It’s so old. I’d like to explore other mediums.” Kerr: “Maybe all this modernist stuff is a cry that film is near the end… Hoolboom: “It’s finished All we can do is talk about what was.” And yet… “On the other hand,” Snow says, “it’s surprising that (experimental film) still exists, that there are young people coming to it. The medium itself still seems inviting and there’s still a lot to be done with it.” Sternberg: “There’s lots of work and what’s good will stay around somehow. And if not, so what?” Brown: “The artist is like a cockroach—we have to be able to eat anything in order to survive. You try to kill us but we keep coming back.” The book’s final words are Cartmell’s: “Certainly I don’t think there’s any reason to be optimistic. But it’s astonishing how things change. A stupid invention in someone’s garage can completely change the way everybody thinks. And there are garages in which the lights are burning all night.”

A related thread is summarized by Snow: “In some ways I can’t understand why experimental film continues to have such a small audience.. I just don’t understand (the) resistance.” Brown observes caustically, “You hardly get any recognition. Avant-garde film is like a pariah, like having leprosy.” More thoughtfully, Kiyooka remarks, “The problem with the reception of marginal art is that the public doesn’t accept it because of where they find it. The context destroys it even before it’s begun.” Issues involving exhibition and reception are staples of the discourse of fringe filmmakers—from “getting screenings” and “the politics of exhibition” (both phrases are Sternberg’s) to self-doubts about one’s own work: “I really liked the films but didn’t expect others would enjoy watching them,” Mead says about the super-8 films he made in film school. When Hoolboom asks Sternberg, “Do we need an audience for this work—do numbers matters? Is there a certain point where public attention wanes so completely that you have to say, okay, let’s pull the plug on this. What if no one comes?” Her reply is, “That’s fine. Then I’ll make it for myself.” Lipskis: “The bottom line for me is to keep making work I think is interesting. I don’t lose sleep over audiences.” Popovich: “Audiences don’t matter… For me the communication isn’t with my audience, it’s with my tools, my medium.” Buitenhuis, on the other hand, says, “I just take my films around…” and not only does she find audiences, but she has discovered that “most insight comes out of discussion rather than in direct response to the work… Response comes when we start talking.”

Buitenhuis’s efforts to “reach other kinds of audiences” and “not preach to the converted” are related to a broader issue addressed, in one way or another, by most of the filmmakers in the book, and it goes to the very heart of what experimental/avant-garde film is, or was, or might be. “Is there an avant-garde today?” Hoolboom asks Brown. “Sure,” he replies, mentioning Hoffman, Sternberg and Chris Gallagher as examples. “Avant-garde means a cutting edge,” Brown continues, “It means taking yourself over the precipice and looking into an abyss and pulling something out of it.” When Hoolboom adds, “Some people would insist that any notion of ‘avant-garde’ includes a political dimension,” Brown fires back, “That’s bullshit. Theory and politics are as fashionable as changing your underwear. The work will last, not the politics… Art is about the politics of seeing and feeling.” Comparable opinions are voiced by Kiyooka: “I don’t make political activist-type films… I think the personal is political,” and Hoffman: “Personal work wasn’t thought of as political back then (the late Seventies) but to my mind it’s the most political.”

For Razutis, “avant-garde” includes “the political, the transformational, the artistic, and those (films) historically linked to other avant-gardes.” Moreover: “I don’t believe it is ‘dead’ or has outlived its usefulness in shaking up the status quo.” Kerr, however, thinks of the avant-garde in historical terms: “(It’s) not something I’m a part of.. When Snow was making Wavelength in New York, that was an avant-garde period. Popovich says much the same thing: “I’m not part of an avant-garde. That was an important term when we were starting out. I don’t see what value it has any more.” Sanguedolce, noting the appropriation of avant-garde techniques in music videos and advertising asks, “Where is the possibility of opposition in all this?” And Cartmell: “There’s an avant-garde that erupts at a certain time, that’s radical and distinct, but eventually it is recuperated and becomes part of a canon and a tradition.” Razutis makes the same point about “underground” film of the Sixties blaming Annette Michelson, P. Adams Sitney and Gene Youngblood for “making schools and movements, which was the beginning of the end: its professionalization, anthologization, academicization. Underground film became art, and that was the demise of the form.”

The creation of “a canon and a tradition,” and the identification of “schools and movements” can be perceived as privileging a-political, formalist work that only a small circle of cognoscenti appreciate. “At what point,” Hoolboom asks Lipskis, “does the practice become elitist and self-serving?” “When the artist becomes arrogant,” Lipskis replies. A somewhat different take on the situation comes from Mangaard, who says that although she doesn’t like to call her work “experimental,” “It gets put into that very male-dominated category.” Calling the experimental film community in Toronto “a boy’s club” and “a closed community,” Mangaard says it is dominated by “attitudes (that) have emerged from the work’s academic base, its masculine history of division.” Hoolboom pushes this argument farther in his interview with Cartmell: “What about the argument that avant-garde film is now, and has traditionally been, a white, male and middle-class preserve. That it’s racist and sexist by exclusion.” And in the bleakest and most condemning characterization of what is, after all, the central subject of his book, Hoolboom asks rhetorically, “Is there any point in making avant-garde films now given its marginality, its inability to see beyond its own formalist history or respond to newer agendas of race, representation and the media? Given the preponderance of white male hegemony, the absence of critical discourse, the lack of exhibition outlets?” It is appropriate that these questions appear in the interview with Cartmell, who has not completed a film in ten years. “I don’t do anything at all,” Cartmell says. “It may be the highest mode of non-compromise. Silence.”

Luckily, neither silence nor abstention from filmmaking has been the collective response of Canadian fringe filmmakers. Nevertheless, it is to Hoolboom’s credit that he poses these difficult questions even if no definitive answers are possible. In effect, he shows the fringe to be contested terrain, not the “closed community” some perceive it to be. Moreover, as Atom Egoyan says in a brief forward to the book, “To treat these films as marginal is to marginalize some integral part of ourselves.” While Hoolboom’s book will not eliminate this marginality, it should at least help to illuminate it.

Introduction by Mike Hoolboom

This volume is a machine for turning pictures into words. This machine is marked, like any, by celebration and sadness. Its appearance is a joy and a puzzle, not because like Groucho Marx I could never join any club that would accept people like me, but because most of my efforts, most of the work of my friends and community, are invisible. And as strange as it is to say, this invisibility is something that brings us happiness. The terrific thing about being an artist who works in film is that movies are important to everyone; they are the stories we tell each other or the stories we ourselves are living. In our best moments and our worst, they are the way we imagine ourselves. The worst thing about being an artist who works in film is that movies are important to everyone. For most of us, “I know what I like” means “I like what I know.” But alongside the great march of television and movies that most of us are on, there are those who have decided to go down the road not taken. They are, we are, the minor literature of cinema, the poetry, the fringe, the underground. We are every dream a company will never have, every longing that does not lead to success. We are everything without a bar code or a corporate sponsor. The work is too long, too short, too disgusting, too beautiful, too boring, or too self-indulgent to fit in. To belong. To be a part of it all. Unlike their mainstream cousins, no two fringe films are alike. There are no series, no reruns, and no commercial breaks. Each is unique, as individual and eccentric as one of your friends. This book, like so many of the films described within it, the venues dedicated to showing it, and the distributors who make this work available, have been made possible by the arts councils in this country. While others are searching for a national culture, they are busy funding it. The list presented here is hardly definitive, nor are these filmers to be taken as the largest, greatest, or grandest of them all. Something in their work touched me, showed me there was another way to fall in love, to speak with a friend, to touch. All of them, or so I’d like to imagine, have moved towards everything that gives them pleasure, and turned that embrace into a shared flicker of light. All have staged the small hole of personality that admits the world, insistently presenting not just what they’re seeing but the act of seeing itself. They are gathered between these covers to speak about the feuds and deaths and marriages and happinesses that have made this seeing possible. Here in the underground, new kinds of lives have made new kinds of pictures possible. Here are their stories. One day they may be yours.

Foreword by Atom Egoyan

Why am I writing the foreword to this book? What does my sensibility and creative orientation have to do with the work discussed here? Where does my world (commercially conceived and distributed feature films) meet the visions and ideas of the experimental filmmakers discussed in this collection? The answer might be in the imaginary audience we both share. I’ve been deeply inspired by artists like Michael Snow, David Rimmer, Phil Hoffman, Peter Mettler, Michael Hoolboom, Barbara Sternberg, and Bruce Elder — not simply because of the extraordinary quality of their work, but also, and perhaps more profoundly, because of the ceaselessly curious and completely trusting nature of the audience they’ve had to imagine for their creative efforts. These filmmakers taught me that there is nothing more exhilarating than to feel self-conscious in front of a screen. The viewer did not have to lose themselves into an image, but could actually observe it, and create a dialogue about that process. This dialogue could be meditative, amusing, and provocative. By watching these films, I learned how to respect and indulge the intelligence of my audience. We dream in moving pictures. Every night, images are conjured in our minds, induced by mysterious and primal needs for sub-conscious expression. I’ve always found it fascinating that the serious attempt to articulate and find meaning to these dreams paralleled the discovery and development of cinema. It’s also fascinating that the essential grammar of mainstream cinema has remained relatively unchanged since the art form’s inception. From the first films, it became evident that there were certain places you could put a camera, and certain places where you couldn’t. No other art form has been so immediately and comprehensively bound by such an orthodox and rigid system. Why did this happen? Was it because of a latent terror that seized us when we discovered a medium so close to our dreams? Or, more to the point, is the traditional grammar of cinema a direct expression of how we dream? Do we dream in multi-angle coverage, with static masters, close-ups, tracking shots, and pans? Do we never cross the magical axis, except when we wake out of our sleep in terror? Is this why the language of early cinema came so quickly — because we’ve been playing it inside our heads forever? I ask these questions because the films discussed in this book come from a different perspective. They are truly revolutionary; not simply because they defy conventional rules of industrial cinema, but because they confront the very nature of what we need to see. We are driven as much by narrative as by impulse, yet mainstream cinema is almost completely concerned with giving expression to ego-based storytelling. Fringe films are id-based. They address, liberated from the moderating influence of narrative, our purest sense of impulse — the way we see. To treat these films as marginal is to marginalize some integral part of ourselves.