A series of talks by Michael Stone about chapter 3 of The Yoga Sutra a text written by mysterious author(s) often named Patanjali in the second century. Notes by MH include reveries and imaginings. Centre of Gravity Fall 2011. www.centreofgravity.org

Barbara

I wanted to start out today by introducing you to an extraordinary women, her name is Barbara Smuts. For 25 years she worked as a scientist in Kenya and Tanzania, getting to know a troop of baboons. “For 2 years, I joined the baboons at dawn and travelled with them until they reached some sleeping cliffs at dusk, 12 hours later. With occasional days off, I repeated this routine seven days a week. For several months, I lived alone and went for days without seeing another human.”

“After doing much of what they did for some times, I felt like I was turning into a baboon. A simple example involves my reactions to the weather. On the savanna during the rainy season, we could see storms approaching from a great distance. The baboons became restless, anticipating a heavy downpour. At the same time, because they wanted to keep eating, they preferred to stay out in the open as long as possible. The baboons had perfected the art of balancing hunger with the need for shelter. Just when it seemed inevitable to me that we would all get drenched, the troop would rise as one and race for the cliffs, reaching protection exactly as big drops began to fall. For many months, I wanted to run well before they did. Then something shifted, and I knew without thinking when it was time to move. I could not attribute this awareness to anything I saw, or heard or smelled; I just knew. Surely it was the same for the baboons. To me, this was a small but significant triumph. I had gone from thinking about the world analytically to experiencing the world directly and intuitively. It was then that something long slumbering awoke inside me, a yearning to be in the world as my ancestors had done, as all creatures were designed to do by aeons of evolution. Lucky me, I was surrounded by experts who could show the way.”

Barbara is a scientist, who writes complicated scientific papers for referereed journals, who speaks at conferences around the world, and publishes books. A professor who has been lauded and won awards, hugely respected. And she uses this word to describe the non-human animals that are around her. She calls them “experts.” What I hear in this word – you must be experts – is the beginning of sangha, is the beginning of us. She doesn’t step up, she steps down, this is your land, this is the place that you belong in. How can I be here with you, how can I make it OK to be here with you? She approaches the baboons very slowly, over a period of months. She is counseled by her wiser advisors, that she shouldn’t have any interactions, she shouldn’t acknowledge them in any overt way, she should be, you know, like a scientist, neutral. As if scientists were neutral. But she found that neutral actually meant negative and aggressive. Imagine someone showing up in your apartment, and just hanging out there, and never talking to you, never looking at you directly, never engaging with you. What could you think? What could you possibly make of that? So while she didn’t make a thing of frolicking with the young baboons who were forever wanting to play, she met the gaze, slightly downturned, of those who approached her, she grunted just as they might grunt, and slowly they understood and she understood that they were not going to be a threat to one another. That despite their obvious differences, these were two kinds of animals who could get along. And more than that, the experts could teach Dr. Smuts, the esteemed, world renowned anthropologist, graduate from Harvard and Stanford, how to sense when the rain was coming, and this is a shared sense, it’s a sense that runs through everyone there, all the animals there, even the human animal, it’s something concrete and embodied, and it’s something that everyone participates in. It’s going to rain, I know it’s going to rain, and I know exactly how long it’s going to take me to get to that shelter over there, right over there, from the place I’m at right now, before it starts raining, so I won’t even get a drop of rain on me. I know time, I know this time, the way I know gravity.

“Another time when I had a bad cold, I fell asleep in the middle of the day, while baboons fed all around me. When I awoke at least an hour later, the troop had disappeared, all but one adolescent male who had decided to take a nap next to me. Plato (we gave the baboons Greek names) stirred when I sat up, and we blinked at each other in the bright light. I greeted him and asked him if he knew where the others were. He headed off in a confident manner and I walked by his side. This was the first time I had ever been alone with one of the baboons, and his comfort with my presence touched me. I felt as if we were friends, out together for an afternoon stroll. He took me right to the other baboons, over a mile away. After that, I always felt a special affinity for Plato.

One experience I especially treasure. The Gombe baboons were traveling to their sleeping trees late in the day, moving slowly down a stream with many small, still pools, a route they often traversed. Without any signal perceptible to me…” Can you hear in this phrase an echo of the moment that each member of the troop feels as the rain begins to gather? It is a shared understanding, an understanding that in the instance of the impending rain, they share not only with each other, they are interdependent not only with each other, they are experiencing a kind of samadhi not only with each other, but they are experiencing interdependence with the sky, with the clouds, with the rain. This is what I think Barbara Smuts means when she names them “experts.” They are “experts” at exactly this form of samadhi, all of them moving as one form, one body, to seek shelter from the rain that has not quite arrived, but they feel the rain, they feel the space before the rain arrives with such precision, with such a certain touch, as if it was already raining, as if the space before the rain was as full, as clear, as filled with touch, as the rain itself. They are samadhi in this moment, and move as one body from the place of feeding to the place of shelter. What lineage are you from? Who was your samadhi teacher? The gombe baboons in Kenya, just before the rainfall.

Let’s continue with Barbara: “Without any signal perceptible to me each baboon sat at the edge of a pool on one of the many smooth rocks that lined the edges of the stream. They sat alone or in small clusters, completely quiet, gazing at the water. Even the perpetually noisy juveniles fell into silent contemplation. I joined them. Half an hour later, again with no perceptible signal, they resumed their journey…” “No perceptible signal” to her, just like for many years Barbara felt no perceptible signal that the rain was coming exactly now. She describes this state as thinking, as analyzing, in other words, she is living in her description of the world, not the world as it is, but she is laying on top of her experience her descriptions of the world, and this description has to be dropped, this is what she is really talking about isn’t she? – how she drops her description of the world, so that she can feel what is actually happening in this moment, the fullness of this moment, and before rainfall she feels it at the same time as the experts, the baboon experts feel it. And then again when the baboons gather by the pool they are similarly led by signals, only Barbara can’t hear them, and so we might surmise that she is back in her analytic mind, she is still living in her description of the world. Why? Because the experts all act the same way, they all take their place, at the same time, by the same pool, they are all quiet, even the young ones, the ones that are never quiet. Even the youngest baboons are experiencing samadhi, integration, interdependence, the youngest baboon experiences this, or so we might imagine, we lesser apes, the human animal, the non-expert.

Here is how Barbara concludes: “Half an hour later, again with no perceptible signal, they resumed their journey in what felt like an almost sacramental procession. I was stunned by this mysterious expression of what I have to think of as baboon sangha. Although I’ve spent years with baboons, I witnessed this only twice, both times at Gombe. I have never heard another primatologist recount such an experience. I sometimes wonder if, on those two occasions, I was granted a glimpse of a dimension of baboon life they do not normally expose to people. These moments reminded me of how little we really know about the “more-than-human world.”

A sacramental procession. Is this how we might describe time itself, sometimes, especially when we’re in time, not aware of time passing, caught in a moment, swept away in a sacramental procession? Can you imagine experiencing the frame of this room from the room’s point of view. Breathing through the floorboards. Admitting this flow of yoga, it’s as if the room is breathing in all of us who are sitting here tonight, and breathing all of us out again. Can you feel yourself just for a moment, not centered in the space of I’m alone over here, looking out from the isolation, the defenses of my sense doors, but as if you were part of the flow, the rhythm of this room, as if you were part of the breath of this room, part of the samadhi of this room. And if you could feel yourself as part of this flow, part of this coming and going, arising and passing away, part of the breath of this room, perhaps we might enter what Barbara Smuts describes, as a sacred procession. The sacred procession of time. Of this moment. And then this moment.

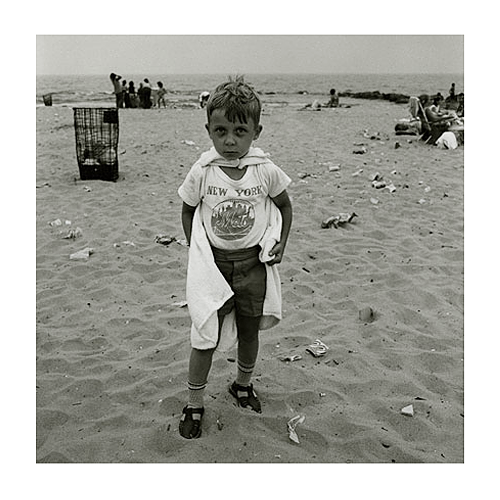

It’s an extraordinary instant that she is describing, brought to her by the experts, but when I read it I can’t help thinking about other experts, I can’t help feeling that this description extends to me an invitation. Can you see what’s happening around you? Can you notice what’s actually going on, to be mindful, as they say in the trade. Are there other sacred gatherings that might appear mysterious, or perhaps not mysterious enough, that are simply overlooked, because we are too busy naming them to notice? Are there people in my life that I could turn to as experts, who could show me how to perform samadhi, how to be fully in my life, in this moment? The way a tree offers its cooling shade, the way a child staggers out onto a lawn, as if they were seeing the infinite colours, the vast spectrum of chroma that we shrink to a single word, green, before flicking it away, without noticing.

Ice

Allow me please another moment of reading, another excerpt, this time from Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s novel One Hundred Years of Solitude. It’s the end of the first chapter, the circus has come to town, and dad and his two kids are standing in front of a gypsy that’s come from a long, long way away, to the small speck of a town called Macondo. Dad is led to the centre of the tent where a giant with a hairy torso and a shaved head waits, standing watch over a pirate chest. Marquez writes, “When it was opened by the giant, the chest gave off a glacial exhalation. Inside there was only an enormous, transparent block with infinite internal needles in which the light of the sunset was broken up into coloured stars. Disconcerted, knowing that the children were waiting for an immediate explanation, Jose Arcadio Buendia ventured a murmur:

“It’s the largest diamond in the world.”

“No,” the gypsy countered. “It’s ice.”

Jose Arcadio Buendia, without understanding, stretched his hand toward the cake, but the giant moved it away. “Five reales more to touch it,” he said. Jose Arcadio Buendia paid them and put his hand on the ice and held it there for several minutes as his heart filled with fear and jubilation at the contact with mystery. Without knowing what to say, he paid ten reales more so that his sons could have that prodigious experience. Little Jose Arcadio refused to touch it. Aureliano, on the other hand, took a step forward and put his hand on it, withdrawing it immediately. “It’s boiling,” he exclaimed, startled. But his father paid no attention to him. Intoxicated by the evidence of the miracle, he forgot at that moment about the frustration of his delirious undertakings and Melquiades’ body, abandoned to the appetite of the squids. He paid another five reales and with his hand on the cake, as if giving testimony on the holy scriptures, he exclaimed:

“This is the great invention of our time.”

Sometimes the experts are a troop of baboons, and sometimes the expert is a block of ice. You know the great invention of our time, the one I’m so busy stuffing into my drink that I don’t notice. I don’t have the time, the inclination, the proclivity, the attitude to feel that feeling, that… how did Barbara put it? That sacramental procession of moment after moment, as the ice drops into your glass, and there you are, face to face with the great invention of our time.

Coffee

Being absorbed, integrated, becoming part of something. Do you remember that scene in Two or Three Things I Know About Her? It’s 1967, it’s Paris, and you’re making a movie so you go the café. The revolution, the revolution of my inner life, the revolution of my city, it’s all going to happen here, in the café. And there’s a couple that aren’t a couple yet, and he’s looking at her as if he’s never been there before, and she’s saying the words, the first words, the words they invented language for, so we could share the music, so we could become together the music of these words. They haven’t got there yet, they haven’t dissolved into the samadhi of the two of them, but they’re on the way, and the way arrives in these unexpected words. And without breaking the flow she tips her creamer into the coffee and the camera runs in close for a look and you see this enormous screen filled with a coffee cup and when the milk enters it’s the whole galaxy, every faraway star is here.

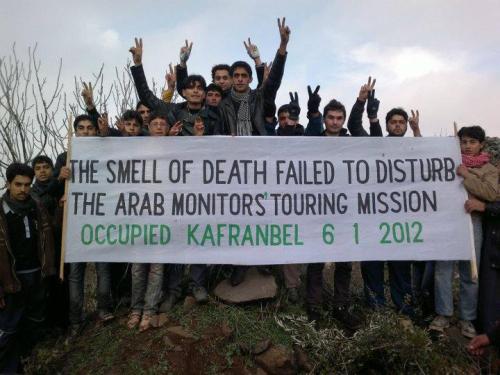

Each morning when I get out of bed I think of the Syrians. I think of the Egyptians. Each morning they get up and they go to the public square. Maybe their best friend is lying half dead in the overcrowded hospital. Maybe their father, their uncle, their grandmother was shot by one of the soldiers who is waiting for them. But still they get out of bed and they go to the square. And their hands are empty. Or perhaps they are carrying some flat bread for their neighbours who will join them, or perhaps they are bringing some water for strangers they’ll meet along the way. All across the country, in every village, in every town, in every city, they are getting out of bed and going to the square. And they are being shot, shot in the eyes now, the soldiers are aiming for their eyes now, but still they are coming. They’re so far away but they feel so close to me. And on the other hand, when my friend Mark died, I couldn’t understand, none of his friends could understand how someone who seemed so close, turned out to be so far away. Why did he have to die before I realized how bad he was feeling? “Focusing with perfect discipline on the moon yields insight about the stars’ position.” Where is my moon? What is my position? How can I bring the people who are close to me, closer? How can I bring the animals, the non-human and animal animals who are far away from me, closer? When I stopped eating meat my friend Lauren said: It’s good that you don’t put all that suffering in your mouth. She said it like eating meat was a kind of reverse eucharist. Take. Eat. This is a body that shows me the limit of what I can love.

Lauren

It was Lauren who introduced me to Barbara Smuts. The great post-human scholar. Lauren is the Canada’s first full time animal studies prof. Crazily smart, the words, the ideas, they just come rushing out of her one after another. And like every really fine talker, she’s an excellent listener. So she’s dishing a class, what is it exactly – Animals and the Law? Animals in Cross-Cultural Perspective, maybe, and somewhere in the class they take a hard look at zoos, which turn out, surprise, surprise, to function more or less like the old slave trade. You know the white imperialists show up in your village and they kidnap you from your family, and maybe some of you get shot along the way, and there’s a long voyage where many of you die, and then you’re stuck in a horrible and faraway place for the rest of your life. And maybe you’re a dolphin, and you keep wondering why they put so much fucking chlorine in the water, because it’s just shredding your skin, your skin is literally falling off. Imagine having to live the rest of your life in a small tank full of mustard gas, or some other chemical weapon that is being released night and day.

So the class looks at pictures, they study the reports, they crunch the numbers, and when the course is over one of Lauren’s students writes her, “I can’t argue with any of the facts but I just like going to zoos.” And Lauren writes her back, “How bad does it have get?” How bad does it have to get exactly before someone, before everyone finally says OK, that’s enough? In other words, how do you make the far away place, into something close. How do you bring the pole star, the moon, here, and feel it as part of your own life?

When I recounted Lauren’s frustration to the great Canadian philosopher Andrea deKeizer she laid down these three sentences that were so perfect they felt like the law, the unnaturally natural order of things. She told me:

We only protect what we love.

We only love what we feel.

This student who is writing my friend understood the problems of zoos intellectually, but she hadn’t felt it in her body, the whole body at once the teacher. When the Buddha says to Ananda, “Be your own authority,” I think he is inviting Ananda to plunge into his own body, to understand the world using the frame of his own body, his own body-mind. This is what we can know for sure. This. This surface, these depths, these sensations passing into and out of awareness. Arising and passing away. Arising and passing away. In the frame of the body. I think what the Buddha is telling Ananda, I think what the great philosopher Andrea is telling me is: Come to your senses.

We only protect what we love.

We only love what we feel.

And then Andrea said, “And we feel so little. How many forgotten animals do we have inside us? Do we have all around us? We’re not protecting what we need to protect because our feeling is so small. We need to bear witness, this is what she was telling me, we need to experience it for ourselves. In our own senses. This is why climate change is so difficult. Everyone knows the statistics, everyone’s heard the warnings. But it’s not real on an experiential level. It’s not real here, here, on the surface of the skin, on the side of my face.

How can I come to my senses around climate change when I can’t see the ice in my glass? When I can’t see that the milk in my coffee cup is the whole universe?

Dad

Last week I went home to Burlington to see my folks. My dad looks like he’s gone 12 rounds with The Crusher. The doctor’s burned all the skin cancer off the left side of his face but complications have left him with a pair of black eyes and his cheeks are the colour of bruised turnips. Now that he has Alzheimer’s he doesn’t talk all that much, days go by with hardly a yes or a no, but because I’m visiting he makes a special effort, and mom’s laid down the dos and don’ts in the daily list he gets before breakfast. “Take a shower. Take your pills. Take a crap in the toilet before you leave the house. No TV when Mike’s here. Talk to your son.” He tries, and then he can’t. And mom and I do all the talking until the phone rings and she leaves. He hasn’t said a word in a few hours now, it’s nothing unusual. In fact, nothing more could be more usual. But then he leans forward in his uneasy chair, and he says, “You know, at night when you’re drinking with friends…” and I look at him once and twice because he doesn’t have friends, and he doesn’t go drinking. And besides usually the small oasis of language that is left to him is right out of the playbook, there are stock phrases he’s learned to repeat. “What would you like a drink sir?” “Ice tea please,” he says. Or: Would you like dessert? And even though he thinks, “Hell yes! I only want dessert.” He’s learned to say, “No, thank you.” As if he ever meant a word he said.

There’s a thing he does with his shoulders, he pulls them together and lifts his hands and smiles as if it to say, “What can you do?” A reminder of easier, older days, perhaps, when his genial demeanour was matched by a rare ability for endlessly witty, post-emotional chit chattery. So I am trying to keep my mouth from falling to the floor because the silent one, the one that’s barely managed a few words in several days now, is launching into something like a story, and not only that, but a story no one has ever heard before. A story about friends and beer apparently, two things he knows absolutely nothing about. He’s on a weekend pass from the prison house of language so he can offer me the edicts of a personal science fiction. “You know at night when you’re drinking with friends, and you’ve had one beer and then two… you’ve had enough beer so that you can start telling the truth. That’s when you can admit that you took a wrong turn. That’s when you can tell your friends that looking back at it all now, you can see how you made a wrong decision.” He slumps back, visibly fatigued with the effort of speaking.

The truth is, he really can’t talk at all, but he’s playing a role, the role of my father, some old synapse is still firing and he’s got his dad voice on now, like he’s offering advice or something, and this allows him to do what is impossible to do, what he hasn’t been able to do for years now. He invents language. He is saying this thing, this terrible beautiful thing, for the first time. He repeats what he just said, he riffs it out again in a variation, and then I ask him, “When you look back, is there always regret dad? Do you always make the wrong decision?” And he does that thing with his shoulders and his hands. That’s the way it is, his body tells me, though he’s smiling as he doesn’t say it. “Sounds pessimistic dad.” “Realistic,” he shoots back, though that’s a shtick. He’s pulled that one right out of the playbook. And then mom comes back into the room and our conversation is finished. He won’t talk again until several hours later when he will announce brightly to the waitress, “Ice tea please!”

What I think my father was trying to tell me was that he made a wrong turn somewhere. Was it his job, marrying my mother, moving to Canada, leaving Indonesia? He’s reaching out of his sadness, and the new loneliness he has now that all of his four languages are unavailable, and he’s telling me that things haven’t worked out the way they were supposed to. That’s he’s lonely and afraid and tired. And that I am his friend, and that he can share that with me too. Beer or no beer. And the only reason he can tell me any of this is because he’s pretending to be my father, he’s stepping up to put the dad suit on one more time, and that allows him to say what he can’t say. It’s just a moment, a small, fleeting moment, in a small fleeting living room. But in that moment, he refuses the habit momentum of his own life, he stops deciding that he already knows, that he already knows he’s someone who can’t speak for instance. And so he begins to invent, in the radical contingency of this moment. And in this moment of invention he breaks the insufferable place of his own solitude, he lets go, and he is freedom.

In my father’s speaking I can feel the fundamental point, the very beginning, the very root of where creativity begins, because he moves outside of his habit patterns, and so at last he is able to make a real choice. And one of those choices, the rarest of all choices, is to invent. And what is his invention? He speaks of his missing inner life. He turns his eldest son into his best friend. Not a king and his kingdom, but a fraternity of equals, where even the most difficult truths can be shared. Where even the most difficult truths can be the path that opens our hearts. He brings us the discovery of ice, the universe of coffee, the baboons rushing to avoid rain.

And then it’s gone, and we’re both ordinary. We take off our superhero tights and capes, we step back into our old shoes. But somewhere in that old familiar place, that dusty place of home, there is a shimmering, call it a glimmer in his eye, a new kind of hope perhaps, because we had lived outside of everything we had ever known, we had breathed in the revolution of the two of us. One word, one moment, at a time. We had come to our senses in order to arrive at this, this moment here, as if we didn’t know what was going to happen. As if we didn’t need to hang onto anything. Not even each other.

A new world is possible. I know because I lived there for a moment with my new best friend. A Buddha and a Buddha had come to occupy our family. Thanks for the offering dad.