Why don’t we start with fear? I’m scared to stand up here today and talk about something that I don’t know enough about. And I’m even more scared not to try and say something, even though I know it won’t be enough, even though I should be sitting where you’re sitting, so I can absorb the lessons that keep getting erased whenever I forget that being white, that my whiteness, is a colour.

Where do we begin when we can’t find the beginning? I’ve been looking for it ever since Officer Darren Wilson took his best shot, I’ve been trying to find a place to begin but I find that I can’t. But after my birthday (oh wait, is this turning into another story about the thing I call myself?), exactly one week later Michael Brown and Dorian Johnson are walking down the middle of the road in Ferguson, Missouri, a suburb of St. Louis. One day you wake up and you get a geography lesson. Does this happen to you? You wake up in the morning and entire parts of the globe that have been absolutely invisible to you are now staring back from the windows, I used to be able to walk the whole Vietnam coastline blindfolded until the Americans turned the killing machine off and left.

You wake up and you’re in Ho Chi Minh City only you’re not. And one day the killing machine turns up in Ferguson, Missouri after the shot… could we call Officer Wilson’s state issue a starting pistol? After starting at the shot from the pistol I’ve been finding myself waking up every day in a city that looks like Ferguson, Missouri.

This is what we know for sure. Michael Brown steals $50 worth of cigarillos and roughs up a minimum-waged, convenience store clerk with his pal. Ten minutes later officer shows up, and their meeting lasts ninety seconds. Pull the car up in front, grab the suspect and pull him into the car window, shoot him, he gets free and starts running so better shoot him again. He turns around with his arms up in the air and bang bang bang until he’s dead.

The shooter and Michael Brown are both 6’4” but that’s not the important fact. The important fact is that the shooter is white, and that Brown is black. They leave Michael lying on the street for four hours, and the reaction shot begins, what they call in gun lingo, the recoil. We are living in the recoil. We are somehow – can you feel that some mornings, the bad taste in your mouth, the way your stomach knots up and you can’t figure why – it means you’ve stepped back into the recoil.

I know I’m supposed to talk about my method up here, and I wrote up a tidy little time-sensitive chitchat about all that, but I wanted instead to talk about something that I don’t want to talk about, because sometimes that’s the only thing worth talking about. I’m a white person and I have the privilege of being able to walk out of this building after our confab is over knowing that the police aren’t going to pull me over for no reason at all, by which I mean I don’t have to keep a squad car up inside my brain where they keep pulling me over and over and over. And that leaves room for so many things, so many extras, you know? It gives me so much space. Or maybe, or maybe you don’t know, what having all that extra space feels like.

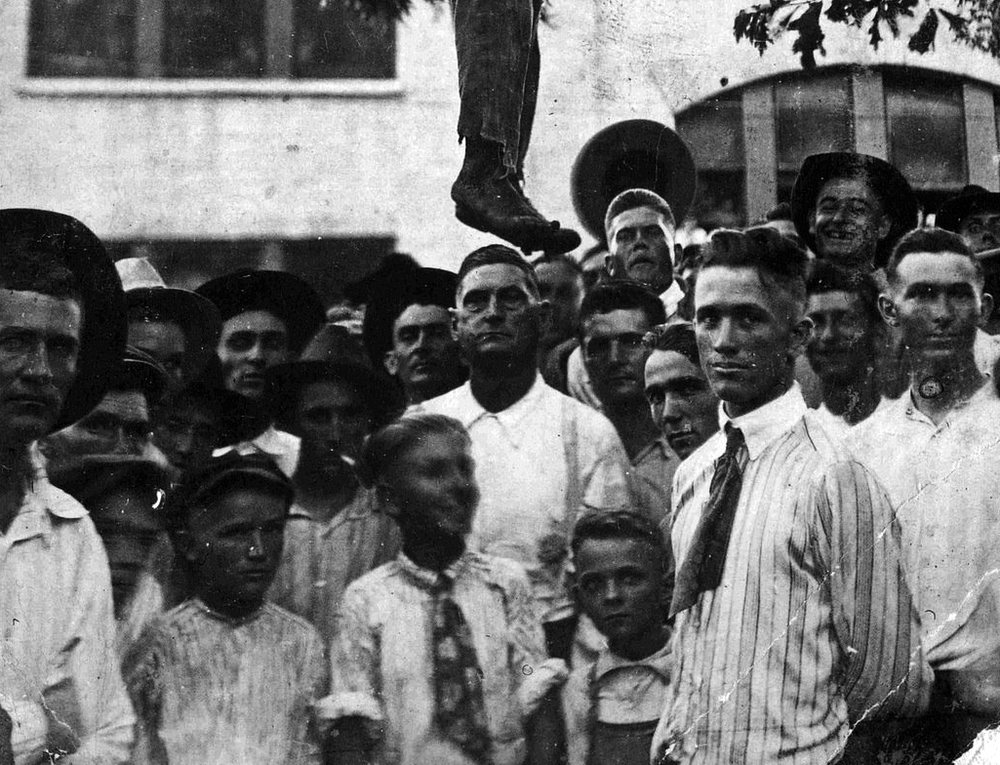

We’ve all seen the pictures of Ferguson burning, the tear gas, the troops looking like Star Wars outtakes. Why are all those white people pointing their big guns at American citizens night after night? And why is it that most of the citizens I see, are black?

Here is Vince Warren, executive director of the Center for Constitutional Rights “Let’s not think about this as these people are burning things here or these people are throwing rocks here, that entire picture that you’re looking at… is the state, the representation of the state of our democracy for black folks in America. (This is what democracy looks like.) It is messy, can be ugly, it’s full of passion but people should not turn away from it. People should not try to tamper down and control it. People should begin to understand that if that is what we are dealing with, if that is where we are as a society, we need to think about structural changes to the status quo… We should be thinking about the folks in Ferguson as pro-democracy protesters, as anti-structural racism protesters.”

I think he’s saying that the people who are living on the streets of Ferguson are voting for democracy. And that voting for democracy, and trying to talk about racism, isn’t always nice or tidy or fine looking. Can we be OK with that? Or is that not OK? And if there were crowds of white people gathering, would the media still be saying it was a “riot,” or is that a word that gets thrown around whenever a few black bodies get together? And why are all those national guard and police, most of them white, why are they posted in Clayton and Kirkwood and South Florissant which are the white areas, but if you go to West Florissant, which is the black area, the police are just letting it all burn.

I’m a filmmaker, and I haul my gear all over town, and I can do that knowing the police aren’t going to assume I’ve stolen it. And if I walk into one of the convenient stores down the block no one’s going to be keeping an extra hairy eyeball on me wondering if I’ve come in there to rip them off. When I talk to my black friends they tell me, everyone of them tells me, about the time, the so many times, they got pulled over by the cops. About the time they were standing talking to a friend and the next minute they’re getting into the back of a squad car while the white friend is wondering what just happened. The time they were told to put their hands up and got patted down while everybody else in the party looks on. These are middle-class folks, we’re talking professors and TV directors, and when I talk to my white pals none of them are telling me the same story.

Vince Warren says: this is what democracy looks like in Ferguson. It makes me wonder: what does democracy look like here, in this city, in this room?

Some mornings I wake up in Ferguson, and I don’t understand the customs of this place, I don’t recognize the codes. What I need is the news that lies behind the news, and that can only be delivered through poetry. And the poet is Claudia Rankine, whose new and important book Citizen is not trying to hide the necessary questions with a lot of answers. That’s why she writes sentences like this:

“In line at the drugstore it’s finally your turn, and then it’s not as he walks in front of you and puts his things on the counter. The cashier says, Sir, she was next. When he turns to you he is truly surprised.

Oh my God, I didn’t see you.

You must be in a hurry, you offer.

No, no, no, I really didn’t see you.”

Rankin’s words make me wonder: what does democracy look like here, in this place, in this room? In other words: who is visible, and who is invisible?

On University Avenue on Tuesday night there was a gathering of folks in front of the American Embassy who were protesting the decision of the grand jury not to prosecute Michael Brown’s killer. Some of the local papers concentrated on the fact that on the event’s Facebook page there was a request that white folks please take a back seat on this one, let the black faces stand up front. And the papers turned that into the story, quoting people about how this was segregation. That’s an awfully big word. It really made me sad. Because it feels like people of colour have to experience racism every single day, but as soon as the issue of race is raised white people and the white press is right there to stand up with them, start shrieking about segregation. In other words, any discussion of how this city, or this room, might be a place where racism exists, all that gets hijacked so that we can keep talking about white people. Keep your eyes on me at all times. Keep your eyes on the white prize and keep them locked in there.

How do you start a discussion that’s never stopped? How can I say out loud the words that I don’t want to say, to hear the stories I can’t listen to because they don’t exist on my personal emotional radio dial? Oh, I didn’t notice you. I didn’t notice that I’m standing in your place, taking up the space you should be in. Projecting my white privilege, that I try to write with white ink on white paper, so no one notices.

There was many pictures posted of the Tuesday evening vigil, and one of them showed a young woman holding a sign that read: Toronto Stands With Ferguson. Before I came here today I made a promise that I would offer this room a question. And it couldn’t be one of the old fashioned kind of questions, like a math question that makes you feel good because you know the answer. It needed to be a question that couldn’t be answered, or that could only be answered again and again.

I remember a moment in Mexico when she stroked my arm in wonder. That long white arm, it had never seemed so white as when she put her coloured arm across it. It was as if she was touching the gold standard, finding the grail, and it made me sick. Stop it. Can’t you stop it? But when I looked into her face I knew that she couldn’t stop it, and I couldn’t stop it. She should have been living in California or what they call without a trace of irony New Mexico, only the Americans stole all that land for white people. First we take what you have, and then we make new standards of beauty so instead of killing us, you’ll want to touch the arm of someone just like me.

This building used to be a school, and like many schools, like most schools, there’s a place in the room that is reserved for the person who is visible, and there’s a place in the room for people who are not so visible. As I stand up here today I feel like a Russian doll, you know those dolls that you open up and then there’s another little doll inside that looks just the same, well that’s me. If you opened me up you’ll find another white guy inside armed and ready to shoot. All those Russian dolls, all the men who have stood right here, right in this place, at the front of this room, they’ve made it possible for me to speak, and they’re making it less possible for someone else to speak. What are they saying? They are saying, “I shot Michael Brown,” or “I covered up the shooting of Michael Brown” or “I’m willing to let an entire part of this city, and many other cities burn to the ground, before I’d give you one of my tribe.”

Here is Claudia Rankine again, from her magnificent book Citizen. The whole thing is written in the second person, instead of saying “I” she says “you,” so there’s no escape. There’s a car, but it’s never the getaway car, because you can never go far enough to get away.

“You are in the dark, in the car, watching the black-tarred street being swallowed by speed; he tells you his dean is making him hire a person of colour when there are so many great writers out there.

You think maybe this is an experiment and you are being tested or retroactively insulted or you have done something that communicates this is an okay conversation to be having…

Why do you feel comfortable saying this to me?…

As usual you drive straight through the moment with the expected backing off of what was previously said. It is not only that confrontation is headache-producing; it is also that you have a destination that doesn’t include acting like this moment isn’t inhabitable, hasn’t happened before, and the before isn’t part of the now as the night darkens and the time shortens between where we are and where we are going.

When you arrive in your driveway and turn off the car, you remain behind the wheel another ten minutes. You fear the night is being locked in and coded on a cellular level and want time to function as a power wash. Sitting there staring at the closed garage door you are reminded that a friend once told you there exists a medical term – John Henryism – for people exposed to stresses stemming from racism. They achieve themselves to death trying to dodge the buildup of erasure. Sherman Jones, the researcher who came up with the term, claimed the physiological costs were high. You hope by sitting in silence you are bucking the trend.”

The young woman at the demo is holding up a sign that reads: Toronto Stands With Ferguson. I promised to come here and offer you a question. Her sign is my question. How does Toronto stand with Ferguson? What does that mean, or what could that mean? Have you had people stand for you, in your life, were there places you couldn’t stand and others stood up with you, even stood up for you? How could we begin to stand up for each other, and tell the awful stories of our difficult encounters, our unwanted encounters with race?