Saul: I went to the Ontario College of Art and graduated in 1976. I specialized in experimental art, video and electronics, though there wasn’t a specific electronics program, I was largely self-taught. There weren’t a lot of people who knew about video, which was a very technical world back then. You had to know the inner workings. I was one of the few people who came out of the art college with that kind of understanding, and CEAC (Centre for Experimental Arts and Communication) was anxious to get me to help run their video facility.

Mike: How did you meet up with the folks at CEAC?

Saul: I don’t remember exactly, they were in the neighbourhood. CEAC was a venue for showing some of the work I was making at the time. I showed videos at the John Street location, there weren’t many places to show then. I managed to broadcast some of my work on TVOntario. Some of my electronics work was exhibited in The Electric Gallery. I went on to run the video facility at CEAC’s Duncan Street location and began applying for grants.

Amerigo Marras was nominally in charge at CEAC, his partner was Suber Corley and he was the one who had a real job. He worked as a high school teacher from the days of the Kensington Arts Association, their first foray into artist-run culture, and saved up enough money to put a down payment on the building at 15 Duncan Street with a matching Wintario grant . Because of the Wintario money, they were committed from then on to having the money invested in art world real estate.

At the Duncan Street building CEAC operated the basement and the fourth floor. We had two long term tenants: an organization called Presentation Services that produced corporate slide shows, and the Liberal Party of Ontario. Both had long term leases so they weren’t covering a high percentage of the operating costs, it was a bit of an economic problem. But with the funding we had from various levels of government we managed to keep things flowing quite nicely. We were there from July 1976 – July 1978. Originally, when we had a very small video facility, we moved it into the basement. When we started to get more equipment we moved it to the top floor, that was well before the punk club or the Funnel began operations in the basement. On the fourth (top) floor there was a large hardwood performance space in the centre, with offices, the library and video studio situated on the periphery of that central space.

I set up the video studio at Duncan Street and oversaw its different incarnations. At the beginning there was a collection of so-called industrial video equipment, there were some black and white video cameras, some portapacks and playback equipment. It was all ½” black and white. Amerigo wanted to put together a facility so that we could show and exchange videos with artists in Europe. Back then the wall that divided our worlds were the different formats. No one had the ability to play back European video anywhere in Canada. In Europe you could buy a machine that could play back all of the formats, whereas in North America the only gear that was available played back only North American NTSC standard format videotapes. CEAC wound up buying a playback deck and monitor from Europe.

We went to Ottawa to meet with the video officer at the Canada Council and lobby him about the necessity of international exchange and multiple format playback. Amerigo, Suber and myself took the overnight train, when we arrived at five in the morning we got in a cab and went downtown to the Canada Council office and waited until they opened. Our meeting lasted about half an hour. What did he say? “I hope you didn’t come all the way from Toronto just to meet with me.” We knew then we were on the wrong side of the grant application for that one.

We also wanted to make video transfers and there were two ways that could be done. European tapes could be digitally transferred to the North American standard, though it was horrendously expensive. The second method was telecine. We would get a film camera and stick it in front of a monitor, record the tape onto film, and then transfer the film back to tape. We never really got to that stage, we were only able to play back international tapes. Though we had a deck that offered colour playback which was a big deal back then.

Then we inherited a collection of video equipment from a group called Video Ring. It was an organization put together by Robert Arn and Michael Haydon. They ran a portable studio out of their van that consisted of one huge broadcast quality colour camera, a collection of black and white cameras, monitors, switching equipment, and special effects generators. We transferred that gear to our studio on Duncan Street. We eventually got enough money to get a video editing system, which was rare and expensive. We spent about $20,000 for a system that would allow you to make very poor quality edits of ¾” inch cassettes. I put together that studio with the help of Amerigo and Suber and a couple of others. Physically setting up the studio was a big deal. We were close to the CN Tower which was a major source of radio interference, we wound up shielding the entire control room with aluminum foil, and grounded it all, and it all worked. Back then the equipment was so sensitive you would get interference through the audio lines, there was a 60 cycle hum through everything. That was when the purpose of the CN Tower was to transmit television signals, which seems funny to think of today.

We taught courses to make sure people knew how to use the equipment. Anyone could take the courses, and anyone was allowed to take the equipment out, provided they had taken a course. There was no formal membership like there was at other artist-run equipment access centres.

The portable equipment was pretty rudimentary, black and white ½” reel to reel videotape. The most interesting piece of gear was the great big colour camera, nobody had anything like that. A lot of editing happened in the studio, there were a couple of other facilities that had portable colour portapacks, but many people came to CEAC to edit their work. If they didn’t know how to edit, I would end up sitting in and pushing the buttons for them. I worked with a lot of very interesting people back then. I edited tapes for a National Film Board workshop run by Doug Leiterman, an independent producer who was doing a series of acting workshops that were shot on ¾” video.

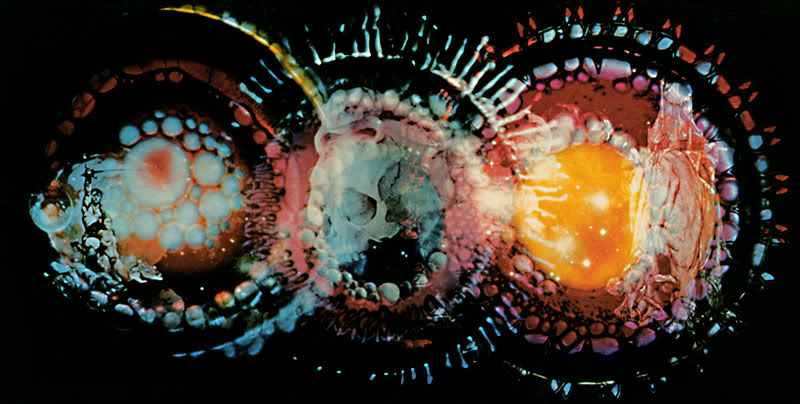

I worked with Joan Chase and John Harham who were The Heavy Water Light Show. They had done lightshows for The Grateful Dead and The Jefferson Airplane. They went on to produce planetarium light shows, mixed media productions that projected films, video and slide projections on the ceiling. They would come into town and do a gig at the ROM for six months, and then move onto another planetarium. They lived on and off in Toronto for a number of years and we became good friends. They brought in footage from multiple formats and relied on CEAC’s editing facilities.

We sometimes used the equipment in-house to document events. There was a group from Sweden called Etoile du Nord, and we helped produce a video of their performance. There were some dance groups that we would occasionally videotape.

Mike: Did you ever attend one of the Funnel’s open film screenings in the CEAC basement?

Saul: No, although I knew Ross McLaren who ran the open screenings because we were both students at the art college at the same time. It had all started with the Kensington Arts Association that begat CEAC that begat the Funnel and the Crash ‘n’ Burn. Each organization seemed to draw from different worlds. Ross might have had more interaction with the Crash ‘n’ Burn than the video and library and performance components.

Mike: In May/June 1978 CEAC delivered performances and lectures in England, France, Belgium, Netherlands, Poland and Italy.

Saul: It was a big deal to get a visa to go to Poland and visit the communist world. Poland was on the periphery of what was going on in Russia, and there was a lot of experimentation in the art world then. I remember Suber and Amerigo saying that they had to convert a certain amount of dollars into Polish zlotys and then couldn’t spend it all because everything was so inexpensive. They would take everyone out to restaurants, beer, food and entertainment were all ridiculously cheap.

I managed to get in on a couple of tours. Amerigo, myself, Lisa Burroughs and a guy from Guelph were invited to the IX International Video Encounter at the University of Mexico in December 1977. Nam June Paik, John Baldessari, and Shigeko Kubota (Nam June’s girlfriend at the time) had also been invited. We were so in awe of the artists that we were grouped together with. We were there for four or five days and it was such an amazing experience for a young artist to be thrown into an international context for the emerging art form of video. We had a gallery exhibition of our work, and there were lectures with simultaneous translation.

December 1977 Amerigo Marras, Nam June Paik and John Baldessari at the IX International Video Encounter at the University of Mexico. Photo by Saul Goldman

Mike: In May 1978 the Toronto Sun published a series of articles/editorials accusing the Canadian government of supporting terrorism because it was funding CEAC, who had been featuring the Red Brigades prominently in their in-house magazine, Strike. This led to debates in the House of Commons and a unilateral funding withdrawal from the arts councils.

Saul: I think we were more surprised than anybody else. Everybody was busy pushing limits on all fronts. Amerigo and Bruce and Ron and all of those people were very interested in the intellectual aspects of revolution. I guess we didn’t realize how dangerous the idea was until the mainstream media decided to pick up on some of the articles that were in Strike (the Magazine). The Toronto Sun/CITY TV broke the news that there was an article in Strike – I don’t know that I actually read the article but knew what the general gist of it was – that argued there were some aspects of what the Red Brigades were doing in Italy that had some justification. The media picked up on it and decided that it wasn’t right for the government to fund an organization that had potentially favourable impressions of what so-called terrorists were doing in Italy. That led to the pulling of the plug by the Canada Council, Ontario Arts Council and Toronto Arts Council, money that we had depended on to keep things going. I remember the media running around the Duncan Street building, one day a cameraman from the Toronto Sun came to get the scoop on this revolutionary terrorist organization that the Canada Council was funding. The reality was that we were just a bunch of artists, no one owned a gun, nobody was interested in doing anything except discussing the philosophies behind what was going on in these various organizations all over the world that were talking about revolution at that time. Within a week the shit hit the fan and things changed, the plugs were pulled. That’s the problem, when you’re depending on political organizations to fund you, support can be easily withdrawn.

Mike: Were you surprised that there wasn’t more support from the arts community?

Saul: In some ways it’s not very surprising. CEAC and the Funnel don’t appear often in the historical records, part of it was because we didn’t have a permanent collection, but a lot of it was because of the fragmentation of the arts community at that time. Every organization depended on grants, so if you got a grant it meant that they didn’t get one. There were both organizations and artists that weren’t disappointed that there was one less mouth to feed.

At the time I was bridging the worlds between business and art and I started to see how small-minded the art scene was. I don’t know if it’s changed dramatically now. I felt that the business world offered more straightforward relationships. When I went on to do retail there was a much more direct interaction with the audience. You show somebody something, it solves a problem, they like it, they give you money, they thank you, and you maintain a relationship for years. In the art world you make a presentation — at the time we were all trying to get big commissions from banks or other organizations that might be interested. They like your work, they spend a lot of time investigating what you’re doing, they’re very impressed, but the project doesn’t go ahead. It’s just such a complicated process. The retail business world was much more direct, people buy it or they don’t, it was a much more pleasant environment to work in.

Mike: Amerigo and Suber left the country after CEAC’s funding was withdrawn in 1978. Did you have discussions with them about their leaving?

Saul: There weren’t a lot of discussions that I was privy to. They moved to New York, and all of us visited them there over the next few years. We brought our kids. They were great people, I enjoyed their company. They had a bad taste about what had gone down in Toronto, particularly the lack of art world support. That disappointment fueled their leaving. Suber hadn’t been able to go back to the United States because he was a draft dodger until US president Jimmy Carter granted unconditional amnesty on January 21, 1977. They bought a building in New York and created another space dedicated to architecture, publishing and performance. I don’t know if it had a name, it was pretty informal. They tried to make a go of it, but the climate for funding was non-existent.

The space became an incredible experiment in architecture, it was in the bowery in Manhattan, on Allen Street. They bought two building disasters on public auction, one was completely uninhabitable, there was no back wall, part of a row of buildings. The other building was filled with squatters. So they had to evict the squatters and then gutted the building and built these incredible Escher-like wooden stairways inside the building. They were still in the process of closing the back wall of the other space and then I don’t know whether they ran out of money or interest or if there were interpersonal conflicts, but the last time we visited in 1985 they had split up. Suber had bought a boat that Amerigo used as an apartment in Manhattan’s Boat Basin while Suber had an apartment near Washington Square. They had lost or sold the buildings already. When they moved to the States, Suber started to get some serious jobs. He worked for Citibank, and did some really interesting computer design programming projects at a fairly high level. He was designing systems for monitoring purchases of customers in supermarkets, when people got an Affinity card that became the ticket for retailers to monitor buying habits. He designed programs that could analyze huge amounts of data. He did that for quite a while when they were in New York.

Back at CEAC, Suber wound up becoming a largely self-taught computer programmer. He worked for a company in Hamilton or Burlington, and would take a GO train every morning and then come back to CEAC in the evening. If we didn’t have enough funding for an event, to pay for Philip Glass or Steve Reich or any of the amazing events they staged, he would basically foot the bill. He was also a great critic. Wonderful performers or artists would show their work at CEAC and I would always ask Suber: so what was it like? His reaction was a pretty typical one: boooring. The vast majority of art was not particularly exciting. But he was a believer in the project and a believer in Amerigo. If Amerigo felt strongly about it, he would go along with it. Though he had pretty definite ideas about what art he liked to get involved in.

Roy Pelletier was an architect friend of Amerigo, he had been part of the Strike collective. Roy and Amerigo bought an old medieval stone tower in Corsica. That became a summer project for the two of them. Originally Amerigo’s background was in architecture. They had a falling out shortly before Amerigo died. Roy had found out from their neighbor in France that Amerigo was in the hospital dying, and they managed to sort things out just before he died of a brain aneurysm. As far as I know Roy still has that property.

After the demise of CEAC there were three of us: Brian Blair, Paul Doucette and myself. We moved from 15 Duncan Street to a small space at 144 Front Street. It was right at the corner of Front and York, at the time there was a Whaler’s Wharf restaurant, so we referred to it as the Whaler’s Wharf building. We rented studio space for a little under a year, it was a transitional space. The problem at that point was that we had abruptly and dramatically lost all of our funding. Traditionally we would go to the bank with a letter from the Canada Council and other funding organizations and say this is our funding for the next year. The bank always loaned us money on the basis of those letters. When the arts councils withdrew their funding the Duncan Street building had to be sold, but we still had equipment and a mandate to run the organization. So we moved into a temporary location on Front Street until we could find another building to re-invest the monies that we had made from the Duncan Street sale. Part of the Duncan Street purchase was privately funded through Suber Corley, the rest was funded via a Wintario grant. We had to reinvest that money in a comparable property and it took us a while to find something.

As a way of funding the Front Street studio we tried to turn CEAC into a semi-commercial video operation, which was a really tough thing to do in those days. We talked to rock bands about video but most weren’t interested, they felt it had little to do with their music or image. There were certainly a lot of musicians who had been around CEAC that we could have worked with but we were just a little too far ahead of the curve. We hired Paul Doucette as our marketing guy and he made cold calls to ad agencies, engineering firms and architects trying to sell our services. We did have moderate success doing educational, promotional and test commercials. John Faichney made a very nice brochure with a price list and we managed to do a lot of very interesting work, unfortunately it didn’t generate enough dollars to keep the wolf from the door. Our lives were economically tenuous.

Brian, Paul and I were at Front Street from 1979-80 and then in 1980 we moved to an old Salvation Army building on Lisgar Street where we stayed for a year. CEAC bought the building. It was essentially a church, an old complicated building that had been added to over the years. There was a main chapel space with a stage that we occasionally used for performances, and added to it was a gymnasium where we housed the video studio. We painted the walls chromakey blue. It had tremendous potential but there was a very old furnace and we had little sustaining funding other that what we could generate through our video productions. We occasionally rented equipment to supplement our needs and worked for ad agencies like Ogilvy & Mather and Benton & Bowles. We made test commercials for them which they would bring to clients to try and sell in order to make a real production. We made a spot for the Royal Canadian Mint, for example. We did a really interesting production for Shoppers Drug Mart. They did a beauty cosmetics fair and we recorded a fashion show for them and then set up a playback at the consumer show they ran.

We did some educational stuff, in fact, Brian went on with one of the clients that we had found back then and developed it into a real business that he recently sold to Saatchi & Saatchi. He was making training videos for Toyota Canada, and then went on to event production at their product launches. They did launches in Hawaii or Las Vegas and he would actually design their product presentation which isn’t quite the scale of the Olympic Opening Ceremonies but not that far off. All that started at CEAC, though he turned it into something different and more substantial. But back at CEAC we just weren’t making enough money to pay the bills, so we were forced to close.

In 1981 I started a company called Computer Sign Systems with Sam and Jack Markle. They owned The Electric Gallery and a sign company that’s still called the Brothers Markle. We began to develop some of the electronic gadgets that I invented. We built electronic control systems for signs, for instance, the 22,000 light bulbs at the Honest Ed’s store were controlled by one of the computers that I built. The Sony sign on the Gardiner Expressway was a computer sign that I had developed. I had built a character generator for doing titles out of a circuit board and a keyboard. I did some interesting artistic commissions, and was teaching part time at the Ontario College of Art which I did for about ten years. After six years of running Computer Sign Systems, we’d done some really interesting work but weren’t making much money. I decided that I enjoyed cycling to work more than the work, it was about a 25K trip each way, so my wife and I opened up a bike shop named Velotique, and ran that for 27 years, until we retired last September 2013.

John Faichney wrote me recently and asked: what happened to the video equipment? I don’t really recall. I thought it went, maybe to Trinity Square Video. What about our permanent collection? I don’t know that there was a large collection to offer. I would sum it up in one story. We once applied to the National Museums of Canada for funding. They sent someone over to check us out. It was the same person who went to the Art Gallery of Ontario, and the Royal Ontario Museum and various other museums across the country. He asked John Faichney, the CEAC librarian: if there was a fire, which three pieces would you save from your permanent collection? John said the stuff was all ephemeral, so ranking was irrelevant. Of course that was the wrong answer, but the reality of the collection we had, and our philosophy, was that the stuff wasn’t really that important by itself. That’s how we thought of it at the time, maybe it’s a short term way of looking at it. In retrospect there are amazing works of art that we lost track of. But we were interested in the process of making, it was about people and relationships. Amerigo was once interviewed by Warren Davis on the CBC who asked him: what is CEAC all about? Amerigo said: it’s the centre for the production and consumption of culture. The storage and archiving of art work was not an important issue at the time. We just didn’t feel that stuff was important, we could always make more of it.