Mike Hoolboom: How did you get involved with CEAC?

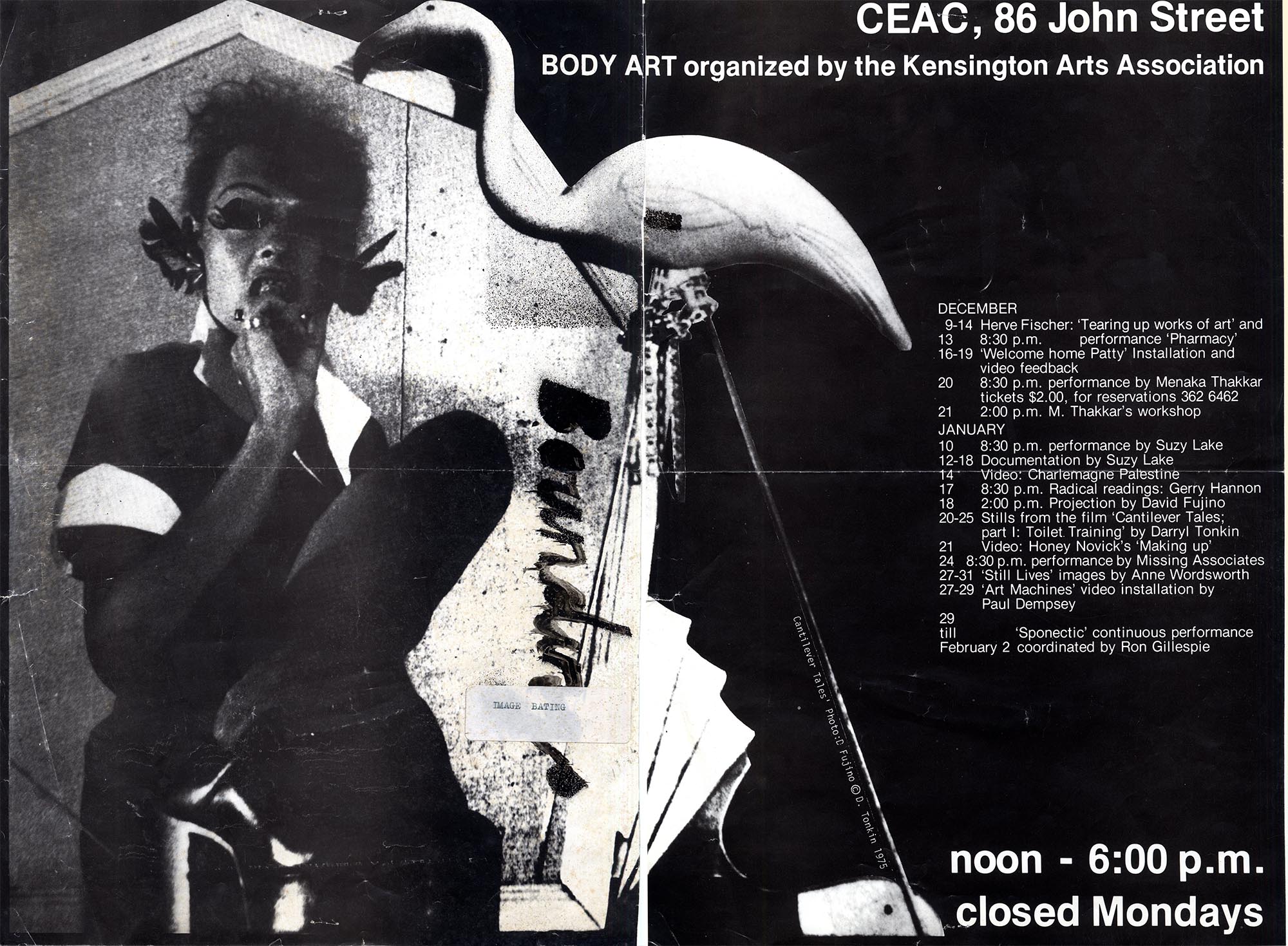

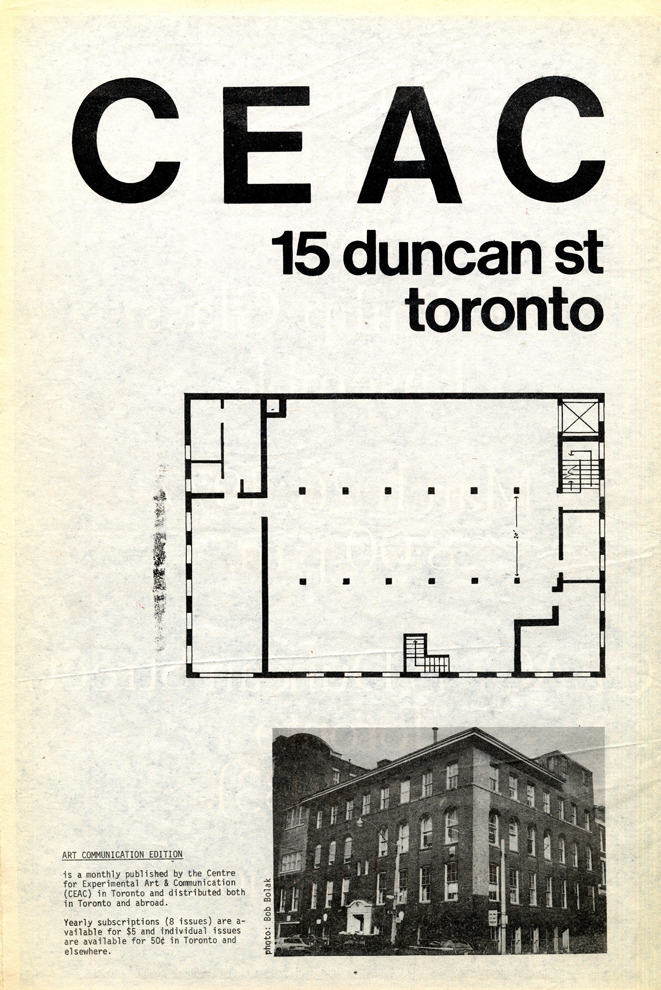

Bruce Eves: For me that period in the late seventies was the last gasp of true artistic freedom. I initially got involved with the precursor to the CEAC, the Kensington Arts Association, right after school in 1975, because there was an involvement with the gay liberation movement and they seemed to be interested in things other than just slapping paintings on the wall, and frankly the space wasn’t as intimidating as the white cube galleries. CEAC evolved out of that house, first in a rented building on John Street in 1976 and a few months later in its final incarnation on Duncan Street.

There were never any exhibitions in the traditional sense at either the John Street or Duncan Street locations. As an art student, I was very interested in conceptual art and the KAA was very much on the same wavelength, so it seemed a natural fit. It’s hard to imagine today, but there was very little activity in the art world at the time. Discounting commercial galleries in and around Yorkville, there was only the Isaacs and Lamanna galleries. Alternative artist-run spaces were only beginning to pop up — KAA and A Space opened in the very early ’70s, Art Metropole around 1975. When the KAA evolved into CEAC and got hold of substantial floor space much of the activity involved performance art and later conferences and tours. Looking back the amount of activity was really rather breath-taking.

Mike: Did the Kensington Arts Association start in Amerigo Marras’s living room? I’m wondering if you could describe the space itself, and what kinds of things you might have seen there. And I’m also wondering if you could elaborate on “gay liberation.” What did that mean exactly in 1975, what kinds of oppression were you feeling, and how was art going to mobilize to deal with that?

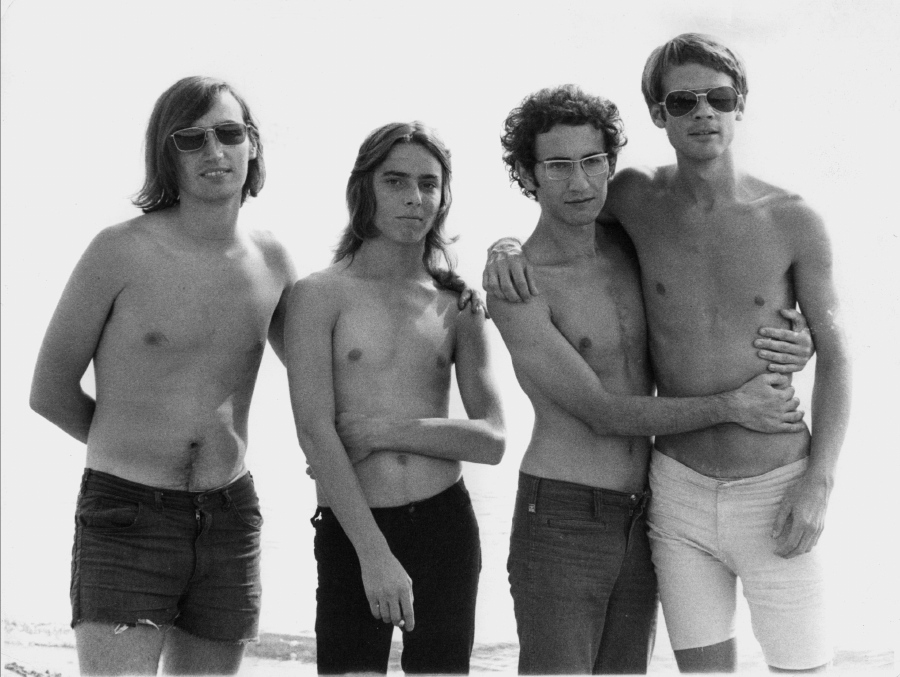

Bruce: In 1970 a loose grouping of people (read commune) living in a vernacular Toronto house at 4 Kensington Avenue formed what would become by 1973, The Body Politic newspaper (the forerunner of Xtra) and the Glad Day Bookstore, which would have been the beginning of the second wave of the gay liberation movement in Toronto. This was spearheaded by Suber Corley, his partner Amerigo Marras, and Jearld Moldenhauer. The Kensington Arts Association was incorporated in 1973 and began its life as an arts space following many of the deconstructivist ideas surrounding conceptual art at the time — neo-Marxism, the relationships between language, art and social practice.

from left: Jearld Moldenhauer, Joey, Amerigo Marras, Donald Suber Corley. Aug. 20, 1972. First Gay Picnic, Hanlan’s Point. Picture by Charlie Dobie

The space itself was the ground floor of the house (with, as I recall, a rather ratty garden) and was decorated with burlap walls (in true late-hippie fashion). After a falling out with Moldenhauer (and having known him somewhat this is not surprising), Glad Day and The Body Politic relocated. The Glad Day bookstore still exists on Yonge Street, south of Wellesley, and is today the longest surviving gay bookstore in North America. There was always an interest in gay issues, but they took a back seat once the KAA got going. At the time I was still a starry-eyed art student so this was a little before my time, but gay issues were much more central to my art practice from that time onward. What did that mean exactly in 1975? Even as late as the mid-70s, society was very harsh in dealing with gay people — there was a lack of job protection, the relationship with the police was always fraught, but more interestingly in this context, the art world was notoriously homophobic (I’d venture to say it still is) — so for anyone to make gay issues a central part of their art practice was quite radical at the time. The issues today are different, and in a way more challenging because with tolerance comes blandness.

Mike: When I interviewed Lisa Steele (Vtape co-founder, maybe you know her?) she said that her entire Kansas City hippie commune was reconvened in Toronto after the boys were drafted for the Vietnam War. Was KAA part of this broad trajectory – young, politically hip draft dodgers coming into the city and making changes? Did you feel that there was a necessary connection between how we live and how we make art and how we make politics?

Bruce: I think what was happening at the time (maybe proving that hindsight has 20/20 vision) was the convergence of a lot of seemingly unrelated social movements: hippies/draft-dodgers, conceptual artists, gay rights activists, artist-run/non-commercial spaces, (and slightly later, but part of the continuum) punk rock. Suber Corley was a draft-dodger from Boston and the KAA began as the host and/or originator of gay activist activities before the art activities took precedence. As well as Lisa Steele and Kensington Arts, General Idea also grew out of a commune (I believe based on Gerard Street). Evidently Amerigo and AA Bronson had a falling out when General Idea refused to participate in the first Gay Pride events because it would hurt their art career.

The involvement with gay liberation issues was definitely over by 1973, and by October of that year the space had been renovated into an art gallery beginning with an exhibition on theoretical/experimental/activist architecture by the French architect Yona Friedman. After this and well into 1975 it was rather a stormy time for artists only interested in producing static objects rather than honouring “the showing of… propositions for non-marketable environments, demountable or temporary objects, illustrated ideas, programmes, and manifestos.” (Amerigo Marras, “Notes and Statements of Activity, Toronto,” Europe, Art Contemporary 3:1 (1977) According to my own CV, I did a performance piece in 1974 and took part in a group exhibition the following year. At this point it is impossible to provide further details (I’d love to know myself!) In 1975 I performed in “Cantilever Tales,” a film shot at 4 Kensington by Darryl Tonkin with themes of black humour and sado-masochism and was screened the next year at the John Street location as part of the Body Art series of performances.

With the move to the John Street location in 1976 the emphasis was on performance art by people/groups such as Missing Associates, Ron Gillespie/Shit Bandit (now Ron Giii), and yours truly. I become much more directly involved, and that space was needed because the programming required it. 4 Kensington was merely the narrow ground floor of a not very large house. John Street, by comparison, was two floors of quasi-industrial space that could easily accommodate large events and elaborate programming. As you can see in the attached photo the floor space was substantial. The third floor mansard roof was added during the building’s later conversion to the Duke of Argyle pub. At that point I was a volunteer pitching in with the renovations of the building; it wouldn’t be until Duncan Street that I was on staff and had official capacities. The John Street building itself was pretty much of a blank slate so the renovations weren’t all that involved and the job was pretty hard-scrabble. The crew was pretty much just Suber Corley, Ron Gillespie and I (believe me, if I was involved with the results were definitely not fancy.)

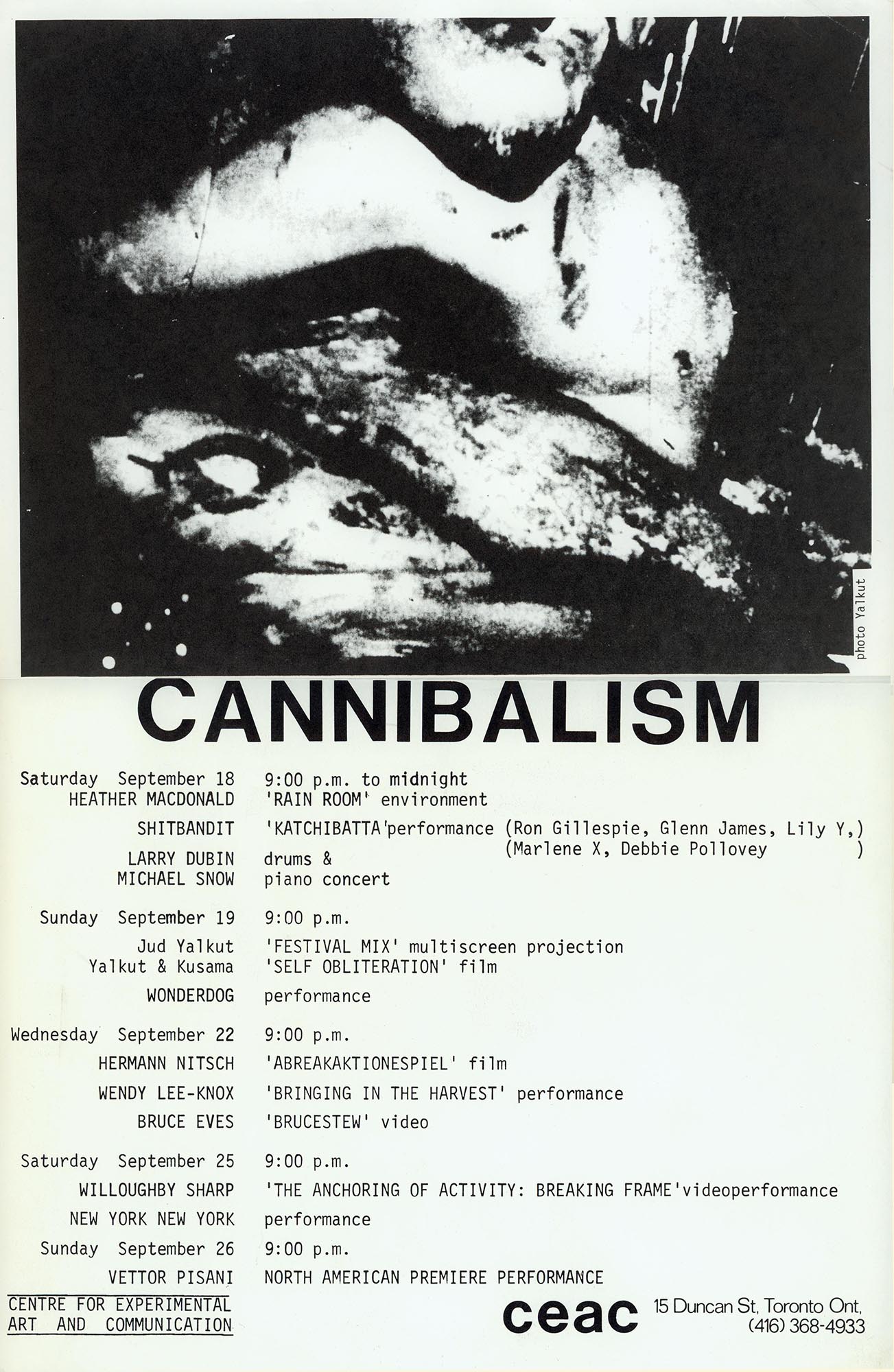

I’m unsure of when the move exactly happened, but I surmise that it was in late 1975 because in January of 1976 an exhibition of body art opened and in April I curated a performance series dealing with S/M that featured Andy Fabo, Wendy Knox-Leet, Paul Dempsey and Ron Gillespie. It’s the only time in memory that I’d seen an audience of leathermen in full regalia (outside of the opera). The space was large enough for Missing Associates to film one of their VERY athletic performance pieces. (They would combine athletics, kung fu, running and jumping in their innovative experimental choreography. Missing Associates was a two person collaboration between Peter Dudar and Lily Eng; sometimes they would bring in others on an ad hoc basis like Diane Boadway, Linda Eng, Henry Kronowetter and myself.) Ron Gillespie’s performance work was heavily influenced by the Vienna school (Herman Nitsch, Arnulf Rainer) and Shitbandit was a loose umbrella of (mostly art students) artists wanting to push the margins of what was deemed acceptable.

The move to John Street also brought the beginning of the international exchanges. Robin Winters, a New York-based performance artist was in residence; and the first European performance art tour happened in the summer of 1976 with Amerigo Marras, Missing Associates, Ron Gillespie, and dancer John Faichney touring a handful of countries from Sweden to Italy. The John Street space only operated until September 1976 when the Duncan Street location officially opened and the CEAC was born. The move from 4 Kensington to John Street to Duncan Street seems very quick — less that twelve months; but given the slow pace of grant approval and the often lengthy time to close a real estate transaction, clearly the end destination was planned and executed at 4 Kensington. The move to Duncan Street was a ground-breaking event — it was the first time in history that an artist-run centre in Canada purchased a permanent home thanks to a $55,000 grant from Wintario. (Today that’s about the cost of a down payment on a shoebox sized condo, but then it was a fortune.)

CEAC, October 1976, first Canadian performance art tour in Europe. Lily Eng, Amerigo Marras, John Faichney, Ron Gillespie (behind John), Peter Dudar.

Mike: When did the name CEAC arrive? Did you feel that the work you were doing (both your performances and curating) were part of the gay lib discussions at 4 Kensington?

Bruce: The CEAC name only entered the vocabulary with the launch of the Duncan Street flagship in September of 1976. Before that the incorporation name was used: Kensington Arts Association. Like I said before, the gay liberation activity in 1973 was very much on the back burner, and I was the only one who picked up the gauntlet and began exploring the signs and signifiers of the gay (male) underground. Aside from the one-off curatorial look into the realm of S/M. There certainly was a continuity of gay issues (if in the background) with the Body Art show in 1976 and its investigation into the body’s political, sexual, and social dimensions — which included Peter Dudar and Lily Eng’s structural dance performances, a screening of the film Cantilever Tales which was my acting debut (a very short-lived ‘career’), as well as the photo manipulations of Suzi Lake. I had an encounter with Mapplethorpe years later and he was very single-minded and a seriously not very nice man; so it’s doubtful he would have participated had he been asked — we just weren’t commercial enough. Had he shown the work he was doing at the time one could guarantee the police would have been involved. The art I was doing was certainly encouraged, and in truth there were limited venues then that would have welcomed unabashedly gay-themed work. There never are for works that are truly avant-garde.

General Idea was dancing around the edges and being euphemistic about being gay (for commercial careerist reasons), and while it’s nostalgic today to talk about “liberation” when being gay is about as controversial as being a blond, at that time, in the early to mid-70s, there were currents of activities working parallel to conceptual artists. I’m thinking of the Cockettes, John Waters, Gilbert and George, Charles Ludlam, General Idea (and me). We were Warhol plus gay liberation. Jack Smith plus gay liberation.

Mike: Did Suber, Amerigo and you live in the John Street location? What was your art practice like, were you more of a writer/thinker/programmer at this moment? Andy Fabo was included in your S/M performance series, why didn’t he become part of the collective? How would you get the word out about events (only posters? I’m guessing there were limited ad funds)?

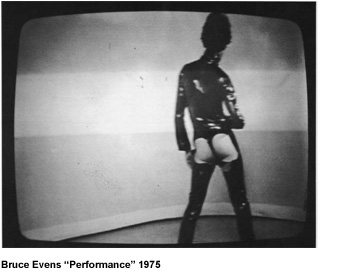

Bruce: Suber and Amerigo lived in a small apartment near Grange Park during the John Street period, and after the final move to Duncan Street the apartment was maintained as a crash pad for visiting artists. Ron Gillespie lived there sometimes, and I used it on occasion. At some point Suber and Amerigo moved into Duncan Street and I lived there as well, and the apartment was eventually given up. This was a time of immense flux for me. I was in the process of finding my voice, both as an artist and as a gay man, and because of shaky financials I spent a lot of my time throughout 1976 at my parent’s place in Newmarket. My involvement with KAA and later CEAC was gradually increasing over the course of 1976 (but crimped severely by being stuck in the burbs). At the time I was making drawings of a proposed series of theoretical, and frankly unrealizable, installations involving bodily fluids (shit walls, cum floors…) and participated in a project with Ryerson to produce a series of multi-camera, broadcast quality videos. My project was intended to be an S/M fashion show but the camera crew stormed out in protest at the appearance on camera of a man naked except for boots, vest, and chaps. The screen grab attached here is from the couple of minutes that was taped, now in the CEAC archives at York University.

My guess as to why Andy Fabo didn’t do anything more than the one-off performance for the series I curated was because his primary involvement was with painting. As far as the types of movies shown, Diane Boadway would be a better bet to describe the goings on. There was no money, so advertising was out of the question and it wasn’t until the fall of that year and the launching of CEAC that there were any publishing ventures to promote the programming. Everything really coalesced for me once the operation moved to Duncan Street and the CEAC appeared. There was at that time the beginning of a core group and we shared roughly the same aesthetic interests. Interestingly, while Peter and Lily are strongly identified with KAA/CEAC, the lion’s share of their work was performed at A Space. What we had in common was a visceral take on traditional media and forms. For example, Lily Eng was trained in classical ballet, but used kung fu as a jumping off point to redefine the limited spheres of dance. Ron Gillespie combined his encyclopedic knowledge of philosophy with a deeply felt influence of the Vienna school and mental health issues to produce performance works the likes of which had never been seen in Canada before. For my part, my body of work has from its beginnings delved into the question of the “gay sensibility.” Forgive me if I cannibalize my own writing, ”but rather than take the standard trip down memory lane into the suck-and-fuck paradigm, I began cherry-picking at will from mutually exclusive sources — the morning headlines, the official record of twentieth century art, the signs and signifiers of the gay male underground — which allowed me to explore the spaces between these charged relationships.” (Artist Statement by Bruce Eves, The Bruce Eves Museum, April 9, 2012, http://bruceevesmuseum.blogspot.ca) If there is any theme within my body of work it concentrates on representative gestures of maleness and explores the demilitarized zone between desire and despair.

“Influenced by the theoretical issues raised by performance and conceptual art, the proposition explored in much of my work is that it should be possible to be simultaneously hot and sweaty and critical and detached…” (Artist Statement by Bruce Eves, The Bruce Eves Museum, April 9, 2012, http://bruceevesmuseum.blogspot.ca) This last statement is, in varying degrees, what we all seemed to share. I liked to think of myself as an amalgam of Aubrey Beardsley and Johnny Rotten. At its core, the discussions were always a neo-Marxist analysis that linked art with the politicization of culture, language, behaviour, and technology. Thus the overriding emphasis on performance art and then later also with video production. Interestingly, none of us are involved with performance art any longer. I do photo-based work, Peter Dudar makes videos, Ron makes sweetly subversive works on paper.

Mike: The Kensington Arts Association is rebranded as CEAC when it moves into the Duncan Street space. Can you talk about the move, the renaming, and your newly central place in organizing events?

Bruce: 15 Duncan Street was built in 1903, among several buildings in the neighbourhood designed by the architect William Rufus Gregg, and remains largely unchanged to this day, unlike John Street (or 4 Kensington for that matter) which have become completely and unrecognizably ugly. According to the City Places column in the Oct 2, 2012 issue of The Grid online, “A new sign recently appeared above the front door of 15 Duncan Street. After over thirty years bearing the nameplate Pope & Company, the entranceway now welcomes clients to Northern Lights Direct. While a direct response advertising agency fits with the building’s recent history as a dignified-looking office building, the experimental artists and punks who hung out there during the 1970s would have satirized its work in a second.”

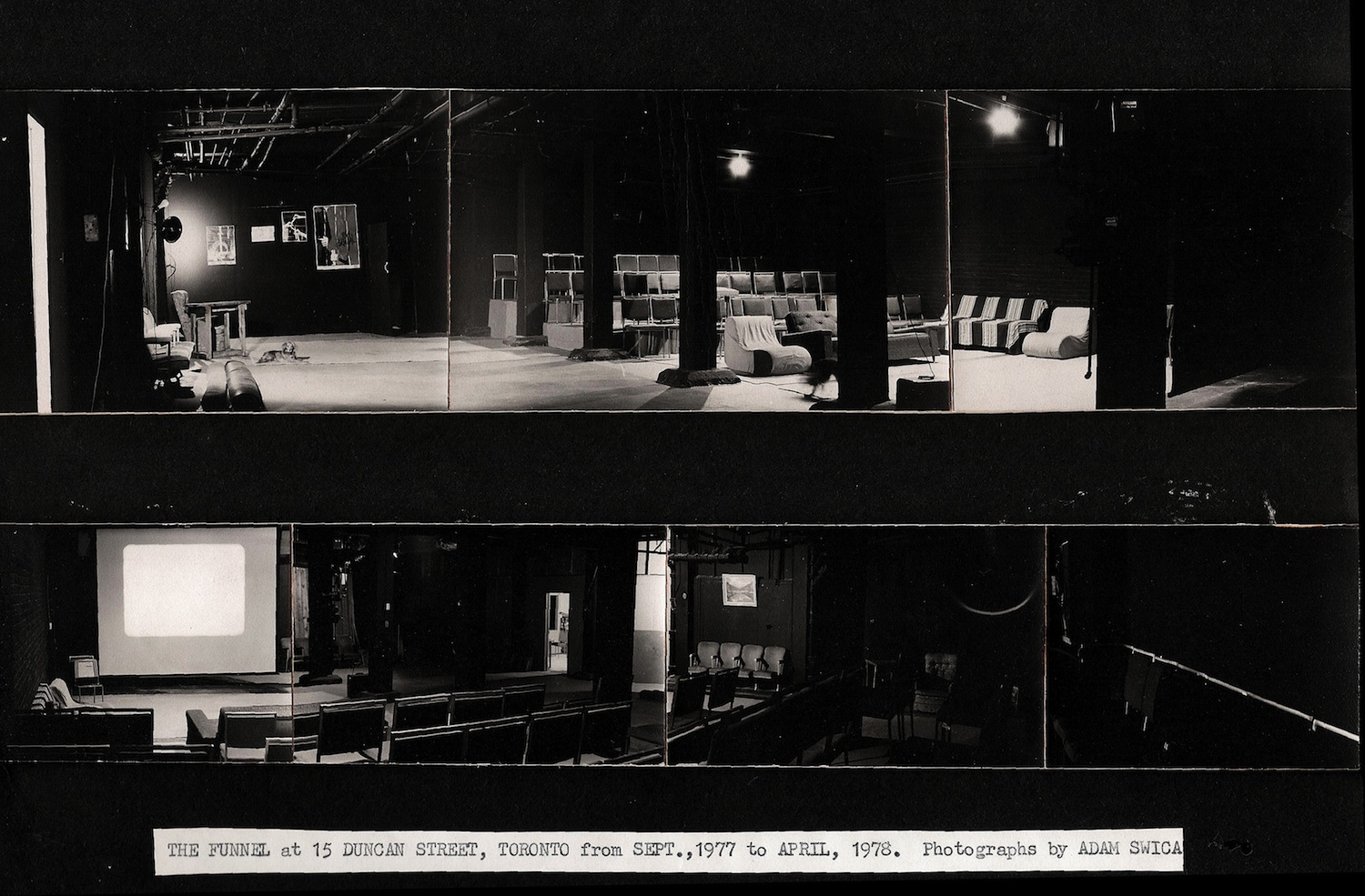

As you can see in the attached photo, the building is a substantial one indeed, and the CEAC occupied the top and bottom floors with the ground and first floors being occupied with pre-existing tenants. I don’t recall the company occupying the first floor but the ground floor was rented by the Liberal Party of Ontario, and both operated standard business hours. Because much of the site had functioned as factories of various sorts since it was built, the spaces were wide open (if broken up by several structural columns) and needing very little in the way of renovation. The southwest corner of the top floor had two small rooms that functioned as offices and the full length of the north part of the building was a separate wing (it seemed to be an addition to the original structure) which housed the library and secure storage. The main performance space was in the middle and was easily the largest gallery space (aside from the museums) in the city. The basement was accessed from Pearl Street and was also an open space similar in format to the top floor. This was the area that would eventually house both the Crash ‘n’ Burn and The Funnel.

Under the rubric of “Cannibalism,” the space officially opened in September of 1976 with a celebratory concert by Michael Snow and Larry Dubin followed by a performance piece by Ron Gillespie titled Katchabatta. Dot Tuer described the piece as “enacting ritual definitions of territory.” (Dot Tuer, “‘The CEAC was banned in Canada’: Program Notes for a Tragicomic Opera in Three Acts,” in Mining the Media Archive: Essays on Art, Technology, and Cultural Resistance (Toronto: YYZ Books, 2005) I would use more caustic (in the good way) language to describe this ground-breaking work. It was the spawn of Pasolini’s Salo and Lord of the Flies performed by the inmates of some discretely high-brow lunatic asylum. There was antagonism toward the audience and it was returned in equal measure. While much of the audience had left after the Michael Snow/Larry Dubin concert, those who remained for Ron Gillespie’s performance witnessed a work that involved both male and female nudity, bondage, raw meat, ritualized dominance/submission, and lit matches thrown at the audience; this was answered with a hail of beer bottles and the performance was ended prematurely in the face of viewer outrage. Evidently the piece was filmed by Ross McLaren.

The only people that eventually lived in the Duncan Street building were Amerigo and Suber (I lived there during the Crash ‘n’ Burn period which was close to a year later) but at the beginning there were issues with the heat which precluded twenty-four hour usage of the building. I remember over the course of that first winter, during a lecture/visit, New Yorkers Liza Béar and Willoughby Sharp from Avalanche magazine insisting, pretentiously and short-sightedly, that staying overnight in anything less than a loft space was simply out of the question — in the morning they were shivering and humbled. At the very, very beginning of the Kensington period it was somewhat commune-like, but by Duncan Street it was much more business-like; the space was used as a living space, clandestinely and roughly, purely for financial reasons, and it was some time before even a shower was installed.

I don’t know what feeling queer actually means but the place was definitely NOT a cruising pick-up place, it was there to do business. However, not being a cloistered monk, I did snag myself a boyfriend from the floor of the Crash ‘n’ Burn and had used the dumpy little apartment on Sullivan Street for the occasional tryst. I was the only one with an active interest in the gay world and would drop by The Body Politic on occasion as they had the top floor of the building on the north-west corner of Adelaide Street, less than a block away. They’d published an interview I’d done with one of the leading gay activists in Italy while on a performance tour stop in Bologna in 1977.

Ross McLaren was always pretty aloof and was around only when his work was shown, beginning with the screenings at John Street. He was evidently approached by Diane Boadway and Amerigo to take charge of weekly open screenings at the Duncan Street building. This eventually evolved into The Funnel. He filmed Ron’s performance at the opening of the building and shot footage at the Crash ‘n’ Burn but he was too remote to be considered a part of the core group (in my opinion). I wouldn’t say that he had a particular project (except for self-promotion) and, personally, I found him to be rather unpleasant. The Funnel’s open screenings at Duncan Street began soon after the opening of CEAC and were documented in Art Communication Edition. One thing I find rather peculiar is that Dot Tuer makes almost no mention of The Funnel in her writing about the CEAC. Because her research was based entirely on the archive at York University, an absence of discussion implies that there was indeed a strict division between the upstairs and downstairs and that the programming and publicity were entirely separate.

My role within CEAC was everything from mopping the floor to doing all the layouts of publications and posters. It was only later that I carried the official sounding title of assistant programming director. Suber was, for lack of a better term, the business manager; and all of the programming was pretty casual in structure. We were all pretty well informed about what was going on anyway, but the trips abroad added to the mix. This began with Amerigo attending an international video symposium in Buenos Aires in 1975 and the first European tour was launched from John Street. One giant ball that was dropped at John Street was not following up on Diane Boadway and Peter Dudar’s suggestion that maybe we should bring up this unknown, but pretty good band called the Talking Heads.

The tours really got rolling in 1977 and that’s where a lot of the cultural exchanges were initiated. It was on my first tour that I did a series of six performance works — they were all site specific, collaborative pieces designed around the limitations of the exhibition spaces and performed by Amerigo, Suber, Diane and myself. Generally speaking, I designed the layout of the pieces and Amerigo wrote the words. Many of the texts proposed antithetical rather than alternative modes of expression in relation to a dominant ideology. Within this was the ironic acknowledgement that such a stance within the context of performance art would lead to failure while speaking from a privileged position within an art world context. I’d taken the position that performance works were to be both situational and site-specific and could be performed only once, otherwise they moved into the realm of theatre (and thus fiction). Employing a hot/cool dichotomy, for the most part the pieces were all rather austere, except for the ones in the Palazzo dei Diamante in Ferrara, Italy and the Galleria Labirynt in Lublin, Poland.

For example, in Amsterdam’s De Appel Gallery the four performers positioned themselves in the corners of the square room with the audience in the center being assaulted by a photographer taking up-close candid shots, while the performers spouted lines in rotation like “Performance art has not yet left the wall.” “The performer and the audience are autonomous.” “Performance art creates no interchange.” Diane Boadway designed the De Appel performance, and was wise enough to keep a diary of the European excursion. She described the tumult in response to the question “Does a repressive society reproduce repressive social models?” during the Ferrara piece. She wrote: “Some students get up on stage and mimic us… then try to hit [a beetle] with a sledge hammer. More students join in, and they rip the paper with the statements and the questions off the wall and take it into the courtyard and burn it in a ritual.” There was much yelling and cursing in Italian.”

The gallery in Lublin occupied the site of a 16th century subterranean brothel with filthy (and I mean filthy!) frescoes decorating the walls and involved both the performers and the audience prowling around a labyrinthine space in the dark with flashlights. Needless to say, language barriers tended to dictate the content and whether or not anything would be spoken. Amerigo spoke Italian, and by that point many countries, though not all, had populations fluent in English. Prior to the second European tour, on a brief foray to New York, I’d created an action for Pier 52 as well as a collaborative work done at Franklin Furnace. The one for the piers was a behavioural event intended to challenge and contextualize the act of cruising. Pier 52 was at that point abandoned and sinking into the Hudson River, with the exception of an intervention by Gordon Matta-Clark (who had cut moon-shaped holes into the walls, causing the city to sue for damages!), and had been clandestinely repurposed by leathermen as a riverside pick-up spot. The participants were Amerigo, Ron Gillespie, Marsha Lore (an artist from Montreal), Dirk Larsen and Tom Puckey of Reindeer Werk (an English performance duo) and myself. Amerigo, Ron and I went into the pier while the others remained in the car with the headlights providing illumination through a hole in the wall (besides, they were afraid to enter the rotten space) to reveal a series of choreographed rituals evoking cruising and anonymous oral sex and implied violence.

Back at home base on Duncan Street, I attempted to execute a couple of the impossible installation designs I’d talked about earlier, and document them with stop motion on super 8 but they were a bit of a fiasco (if I may be blunt). Otherwise, I was mostly involved with the day-to-day operations around the centre. When CEAC moved to Duncan Street, international performers were brought in such as the Philip Glass Ensemble, Reindeerwerk, the Polish contextualists, as well as the Crash ‘n’ Burn. I can think of three occasions off the top of my head when we took bands on the road to collaborate in performance pieces or were part of the bill.

While CEAC’s non-commercial stance was well established by 1975 with the “Language and Structure in North America” show, the conferences and workshops didn’t really get going until the following year (and not all of them happened in Toronto). The first foray into both the conference format and operating internationally would have been Amerigo’s participation in an international video symposium in Buenos Aires late that same year. Attendance at this event enabled him to both connect directly with like-minded artists as well as reinforce the desire to utilize video as an alternative information system. By the Duncan Street period there was an active program of not only collecting work made utilizing video technology but documenting the events happening within the building.

On the first European tours in the summer and fall of 1976 we held discussions in Paris with the Collectif d’Art Sociologique and with the Contextual Art group in Warsaw. Most significantly, we stumbled upon the English translation of a proposition by the Polish artist and theorist Jan Świdziński that intended to overthrow conceptual art as the dominant mode of avant-garde practice. In the early 1970s Świdziński wrote manifestos and produced art works based on radical ideas about the importance of working within a specific socio-political context. His “Sixteen Points of the Contextual Art Manifesto” articulated in one document what Dot Tuer would describe as a “synthesis of KAA’s programming strategy to date… as the paradigm by which didactic, interrogative, and situational performance art realized an ‘object’ of social practice through the dialectic of meaning created between the audience and the performers.” (Dot Tuer, “‘The CEAC was banned in Canada’: Program Notes for a Tragicomic Opera in Three Acts,” in Mining the Media Archive: Essays on Art, Technology, and Cultural Resistance (Toronto: YYZ Books, 2005) Armed with this synthesis, it was the opening of the Duncan Street building and the launch of CEAC that the place began firing on all cylinders.

Perhaps the most high profile and most contentious event that fall was the “Contextual Art Conference” of November 1976. Along with Świdziński and Anna Kutera from the Contextual Art movement in Poland, invited participants included Joseph Kosuth, Sarah Charlesworth, and Anthony McCall from New York, Hervé Fisher from the Collectif d’Art Sociologique in Paris and Jo-Anne Birney-Danzker from Flash Art magazine and local luminaries Karl Beveridge and Carol Condé, A.A. Bronson, Ron Gillespie, John Faichney, and others. The conference was chaired by Amerigo Marras and featured two days of posturing and defensiveness, personal invective and dismissive hostility. Świdziński viewed conceptual art as merely an extension of formalism and believed that after conceptualism, art defined as an institution became a separate, evolving language with its own history but also its own trends and fashions that was known solely to a closed circle of people. As Łukasz Ronduda stated in Art Margins, “Art became a nominalist phenomenon, a discourse that exists only for specialists. According to Świdziński, the sustaining significance of the discourse in the broader cultural context depended on the intellectual and moral prowess of these specialists.” The New Yorkers — Kosuth et al — would have none of it, condemning the conference and, in Dot’s words “revealed the arrogance of artists producing at the [then] cultural centre who felt no obligation… with a clear understanding of their aims.” (Dot Tuer, “‘The CEAC was banned in Canada’: Program Notes for a Tragicomic Opera in Three Acts,” in Mining the Media Archive: Essays on Art, Technology, and Cultural Resistance (Toronto: YYZ Books, 2005)

Given that to today’s ears the language and jargon tossed around seems dated and obtuse; this was perhaps the first time that politically engaged art was, within the context of the 1970s, given the attention that it deserved. I think it is not without irony that just a few weeks later conceptual art would be utterly denounced by Lucy Lippard, the movement’s godmother and chief propagandist. “Conceptual Art’s democratizing efforts and physical vehicles were canceled out by its neutral elitist content and its patronizing approach. From around 1967 to 1971, many of us involved in Conceptual Art saw that content as pretty revolutionary and thought of ourselves as rebels against the cool, hostile artifacts of the prevailing formalist and minimalist art. But we were so totally enveloped in the middle class approach to everything we did and saw, we couldn’t perceive how that pseudo-academic narrative piece or that art-world oriented action in the street were deprived of any revolutionary content by the fact that it was usually incomprehensible and alienating to the people ‘out there,’ no matter how fashionably downwardly mobile it might be in the art world.” (The Pink Glass Swan: Upward and Downward Mobility in the Art World by Lucy Lippard, Heresies #1 Feminism Art Politics, 1977)

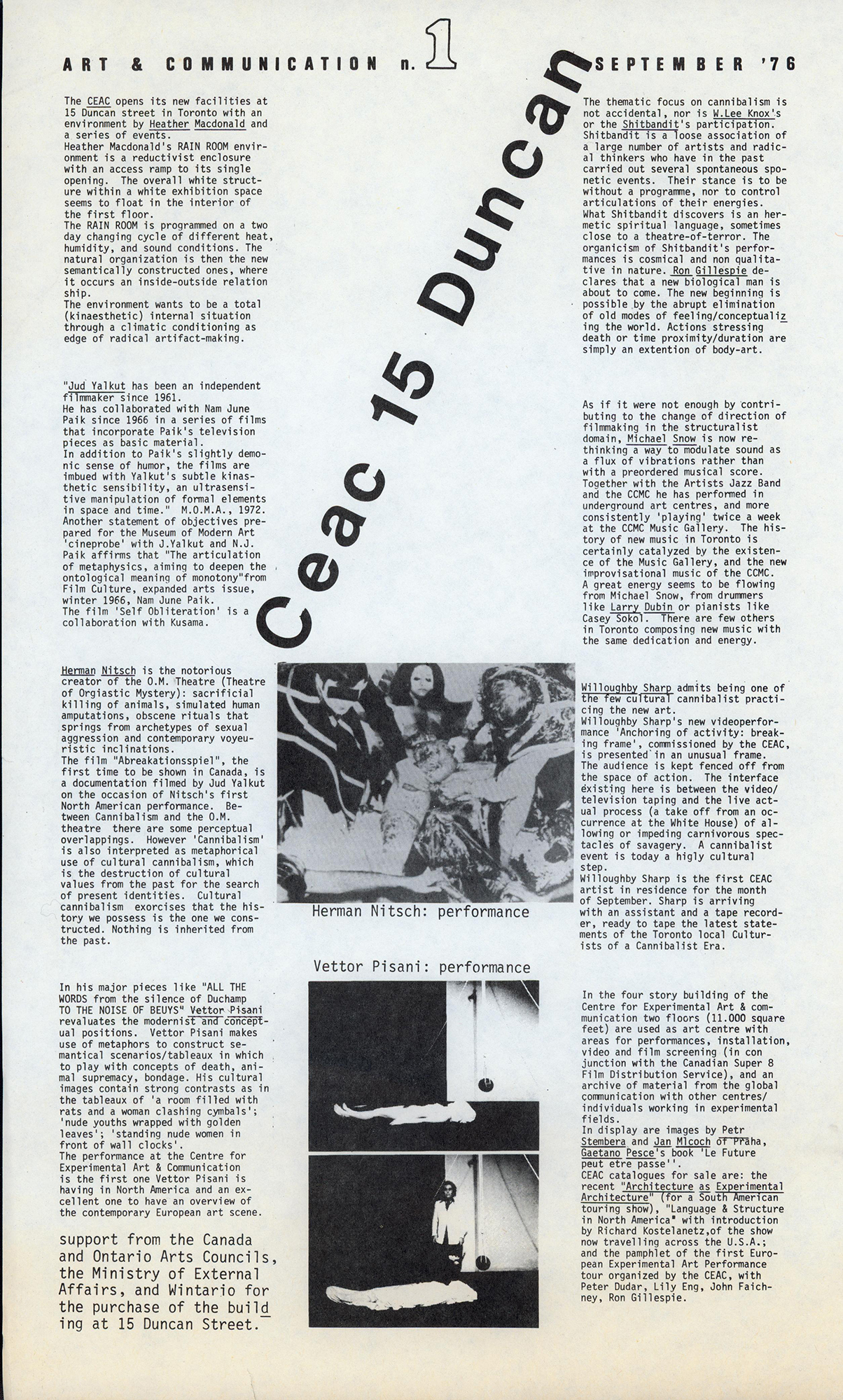

One thing I failed to mention, or to explain more clearly, was the importance of creating an alternate voice to the mainstream media. It seems quaint to talk about utilizing video to formulate an alternative information system in a time of immediate communication and literally thousands of competing voices worldwide in the form of blogs and websites. But in the late ‘70s it was an issue given serious thought. Also, I’ve failed the emphasize the importance of Art Communication Edition, the monthly broadsheet that advertised both future events and chronicled and archived their results. It also provided a publishing platform for the writings of the artists and theorists that haunted the halls of Duncan Street.

There were nine issue of Art Communication Edition in total that were published monthly from 1976-77 after the move to Duncan Street. It was the standard tabloid newsprint format, 11”x17” page size, black and white, and between 32-36 pages per issue. It was edited by Amerigo. I did all the layouts and distribution (which amounted to dropping off piles at art galleries and art gallery friendly bookstores, exactly in the same way that art things get distributed today). Described in Artists’ Magazine: An Alternative Space for Art, 2011; MIT Press, as “a monthly tabloid that sought to be a forum for neglected aspects of contemporary art activity,” Art Communication Edition was both an advertising vehicle for upcoming events at Duncan Street and a forum for theoretical writing about art. For example, the contents of issue # 9 included Peter Byrne’s The Art of Madness; Francesco Saverio Dodaro’s The Re-Appropriation of Power; Analogical Aesthetics by Lew Thomas; Creative Accessibility By Default: The Potential of Super 8 by Roy Pelletier; Alan Sondheim’s Note on Time-Lapse Photography; Blueprint of a Gallery Space by Harley W. Lond; and Alternative Work Process by Amerigo Marras. During the Crash ‘n’ Burn period a couple of pages per issue were devoted to promoting the bands playing downstairs, as well as the two performance events where we travelled with bands in tow, first as an artist/band collaboration at the London Art Gallery and later at Alternative Space in Detroit as part of a twenty-four hour performance marathon called “No Entropy.”

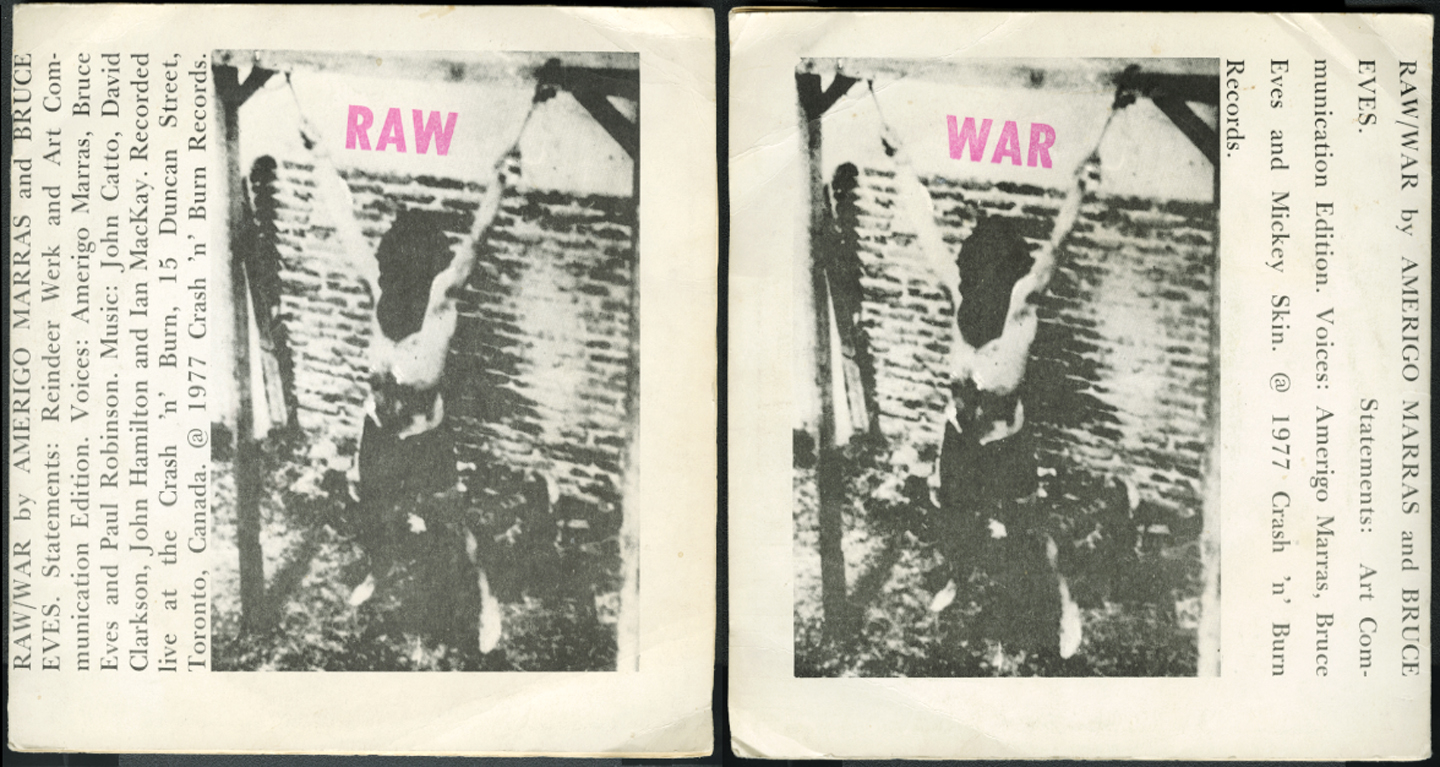

Issue #8 was a 45 rpm record titled “Raw/War” and was a collaboration between Amerigo, myself, The Diodes, and Mickey Skin from The Curse. (This recording is evidently the rarest artifact of Toronto punk).

Issue #7 summarized the Violence and Behaviour Workshop at the Free International University for Creative and Interdisciplinary Research at Documenta 6. Every year during Documenta, a survey of the best in cutting-edge art that happens roughly every five years, Joseph Beuys would install himself in the Fridericianum (a lavish 18th century palace that remains one of the oldest museums in Europe) for 100 days and become Headmaster of Free International University. As described by David Adams in On Joseph Beuys and Anthroposophy “the Free International University program at Documenta 6 dealt with a range of contemporary social themes and issues where radical and creative new thinking was needed to overcome existing problems, including human rights, urban decay, nuclear energy, migrancy, the Third World, violence, Northern Ireland, manipulation by mass communications media, and unemployment. These topics were discussed in an interdisciplinary way by a changing stream of international politicians, lawyers, economists, trade unionists, journalists, community workers, sociologists, actors, musicians, and artists.” (On Joseph Beuys and Anthroposophy by David Adams, Penn Valley, California, 1998)

Fridericianum, where Joseph Beuys acted as the head of his free university for 100 days during the Venice Biennale in 1977

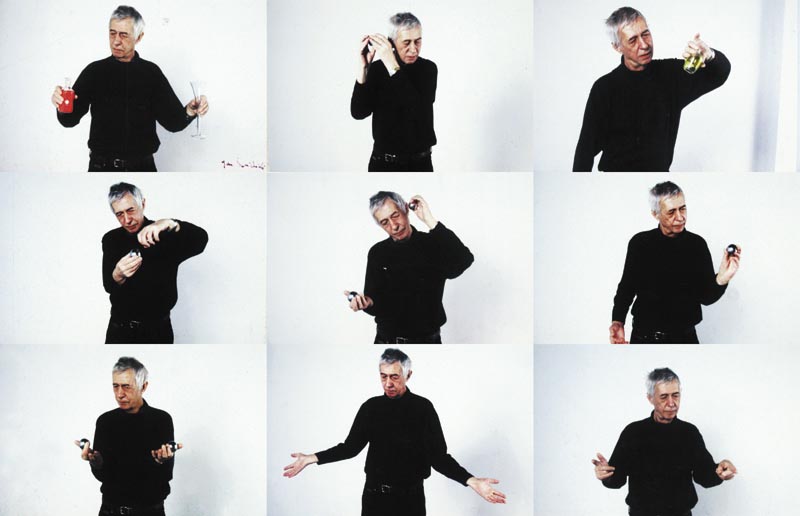

The participants invited to participate in Beuys’s “Violence and Behaviour” workshop included a contingent from the CEAC; a group from South Africa, Reindeer Werk; and a contingent of the Polish Contextualists. I have read that we represented Canada at Documenta 6 — this implies government involvement and this is incorrect — we were invited by Beuys and represented only ourselves. While Beuys was installed in the museum for the entire run of the exhibition, the “Violence and Behaviour workshop” was only a small part of his program and lasted at most a week to ten days. In the attached composite photo, I am next to Beuys at the far right, videotaping one of the performances. (I’m assuming I was taping Lily Eng because she has footage of herself from the events in Kassel.) Amerigo is the figure standing in profile in the center left of the photo. Lily and Ron both presented heart-stopping work and my lecture on homoeroticism and the simulacra of violence in punk and BDSM, while praised afterwards, aroused much hostility from the audience in attendance. At the after-party, when the worship had finished, Beuys launched into a series of demeaning and contemptuous impersonations of his invited guests and ended his thanks by sticking his tongue down my throat. Beuys thought of us as his students; we came to think of ourselves as props. He was a HORRIBLE man, and when he died in 1986 I didn’t shed a tear (crocodile or otherwise).

Joseph Beuys (standing near ladder with hat), Bruce Eves (videotaping), Amerigo Marras (standing, centre left), Lily Eng (subject of taping, offscreen)

By the time of the Crash ‘n’ Burn there were events happening literally every day – it almost had the intensity of a latter-day Warhol’s Factory (but minus the drugs). It was however, in retrospect, the beginning of the end. At this point the contradictions between theory and practice could no longer be kept under wraps – we were cavorting with art stars and using up frequent flyer miles while at the same time blabbing on endlessly about bourgeois individualism and dominant culture.

I think there was never a question of how large an audience was, or whether it was the right or wrong one, and the situation is similar today; in fact it’s my contention that if all the art spaces closed down tomorrow almost no one would notice. Walking through 401 Richmond Street (home to many galleries, media art distributors, festivals, art magazines) any day of the week leaves one with the feeling of loneliness so extreme that it approaches existential angst and alienation.

CEAC was busy but it was never a hangout place. Earlier when I made a (half-facetious) comparison with Warhol’s Factory it was to highlight the amount of activity, but there was none of the drugs, sex, crashing (or beer) – it was actually quite business-like, in a mid-70s sort of way. There were the marquee events like the Contextual Art Conference; the Philip Glass Ensemble performing the music from “Einstein on the Beach”; the series of seminars under the umbrella title of “Five Polemics to the Notion of Anthropology”; plus the Crash ‘n’ Burn and the performance tours. The space was so large and accommodating that it begged to be used to document performance works – Missing Associates filmed “Crash Points 2” there and Lawrence Weiner recorded an audio work titled “Strike While The Iron Is Hot.” There was much discussion between Amerigo and myself about the potential perils of inviting Philip Glass after the Steve Reich debacle; but Glass was Reich’s opposite in every way. The concert was a triumph; and I remember a giant after-party banquet in Chinatown with the whole ensemble. Not everything that was put on was well attended, but many of the events were smashing successes; and of course there were always dunderheaded artists complaining about the fact that there were never any exhibition (in the old sense of the word) opportunities. That’s not something I think we ever needed to apologize for. A rift did develop among a couple of people involved with the Funnel over this very issue, but the door was firmly locked against exhibitions of traditional media. Frustratingly it was rehashing a battle from the early days of KAA on Kensington Avenue as the mandate had changed little up to that point to foster “the showing of . . . propositions for non-marketable environments, demountable or temporary objects, illustrated ideas, programmes, and manifestos.” (Amerigo Marras, “Notes and Statements of Activity, Toronto,” Europe, Art Contemporary 3:1 (1977)”

Dot Tuer lists a dizzying series of workshops on offer at CEAC: “Ron Gillespie and Veronica Lornager’s Introductory Seminar on Evolution; Harry Pasternak’s Kindergarten and Inflato-Art; Saul Goldman’s Video Cassette Editing, Amerigo Marras’s Art and Revolution; and Lilly Chiro’s Buddha Maitrey Anne Wears a Purple Taffeta Dress.” (Dot Tuer, “‘The CEAC was banned in Canada’: Program Notes for a Tragicomic Opera in Three Acts,” in Mining the Media Archive: Essays on Art, Technology, and Cultural Resistance (Toronto: YYZ Books, 2005) My participation in the workshops was only an involvement with the planning phase, and with the exception of a series named “Five Polemics to the Notion of Anthropology” the other courses gathered under the general, if overblown, heading of CEAC School were a bit of a flop. I remember the workshops as being either ill-attended and ill-conceived little vanity projects or a glorified day care centre. This idea was a direct outgrowth of the participation in Documenta and Beuys’ Free International University and didn’t last long. The plans for the ‘Anthropology’ series on the other hand were far more ambitious in scope and star power and approached the Contextual Art Conference in intensity and importance.

The Ontario College of Art’s radical president Roy Ascott (1971-73) had introduced a multi-disciplinary approach to art education, and I remember the college advertising for “magpies” when looking for the new, mostly non-art staff that would make it a reality. As a reflection of these au courant rethinkings, CEAC brought in non-art specialists to work in an art environment. The series of seminars under the umbrella title of “Five Polemics to the Notion of Anthropology” brought in Bernard-Henri Levy, the nouveau philosophe from Paris, Bruno Raminez of Montréal from Zerowork, amongst others. It’s been written that Marina Abramovic was a participating artist but this is incorrect, we’d met her and her partner Ulay at Documenta and I’m sure she would have been invited to perform in Toronto, but she did not attend. There were also plans to create a “Toronto campus” (for lack of better words) of Joseph Beuys’ Free International University.

One name that has gone unmentioned in this account is Heather Macdonald. She was an environmental artist with supreme talent, and was in some ways on the margins of KAA/CEAC until her despair over lack of funding and the precariousness of artists’ housing and workspace led to her suicide in the fall of 1976. Her plight cast a shadow over the place and honed our outrage over the flippant and condescending attitudes of cultural institutions toward the daily struggles faced by the artists they claimed to support. When the Duncan Street space opened, Heather’s “Rain Room” was installed in the basement level. Quoting Eileen Thalenberg’s review in Artscanada: “The environmental structure is an eight foot cubic white room with a ramp leading up to a door in the centre of one wall. Inside, the floor is covered with white stones and on the ceiling there are a grid of copper piping, six heat lamps, and two loud-speakers. The copper piping is perforated at regular intervals and when the water is turned on the rain creates a vertical grid. When the rain stops, the heat lamps suffuse the room with a soft rose glow, causing the water to evaporate. The warm air becomes humid and the final stage of the cycle is hot and arid. The speakers counterpoint the climatic changes with opposing sounds… Rain Room, an elegant, well-constructed piece, has an eerie stillness about it which lies somewhere between a sauna and a gas chamber. It is visually hard-edge, with its romantic content lending a softness. Its only major flaw is that it rests between two modes: environmental and Conceptual. The structure of the environment is physical; the experience within it is Conceptual. The delight in the work lies in the idea rather than in the experience: how many viewers have actually sat in that room for the duration of the six-day cycle? Most of us just open the door, look in, and read about the rest in the explanatory notes. We become cursory samplers of the process rather than active participants, and we experience intellectually rather than physically.” (Review by Eileen Thalenberg, ArtsCanada, December 1976/January 1977)

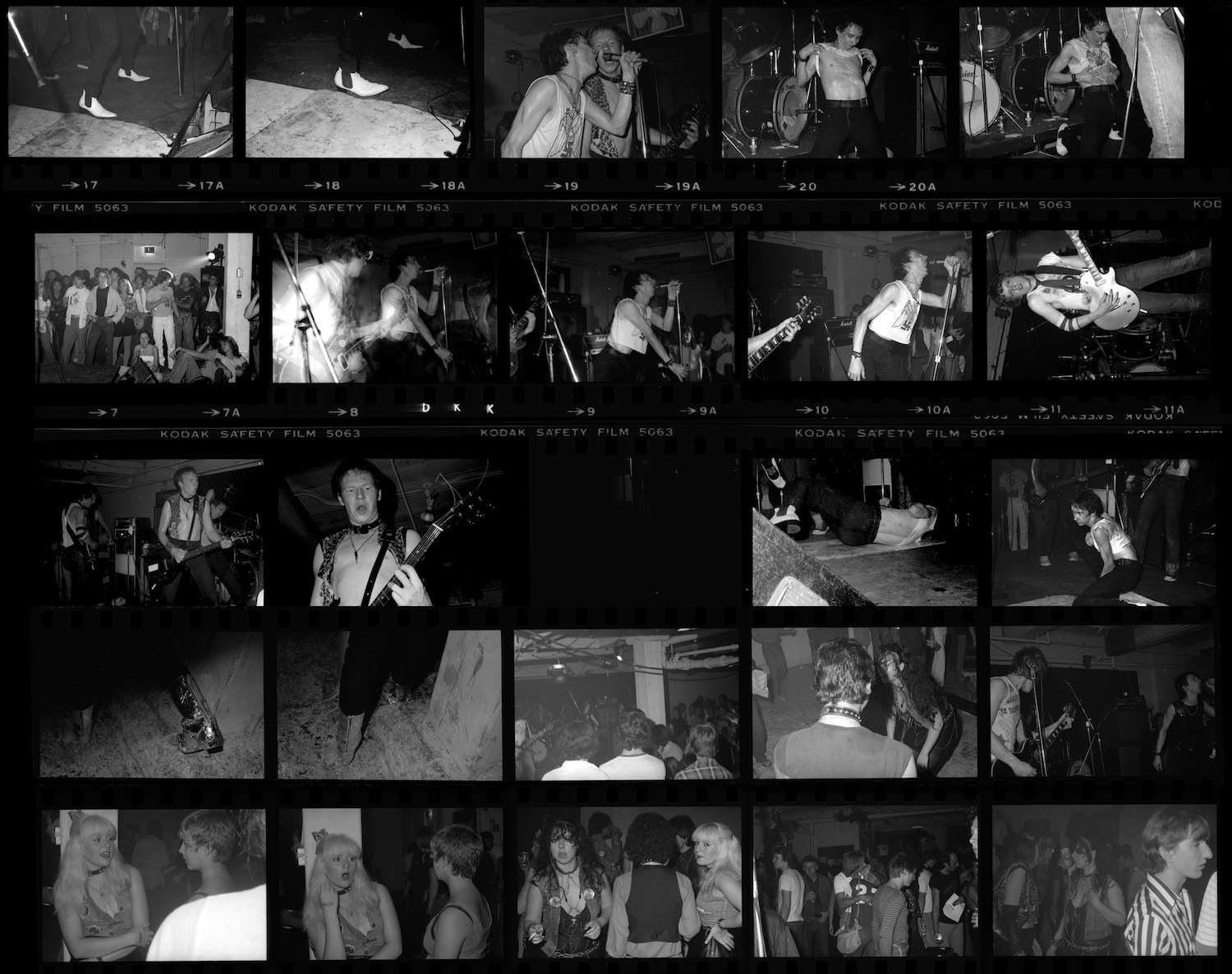

After the Talking Heads (finally) made it to Toronto with a packed performance in the auditorium of the Ontario College of Art, the punk rock buzz was in the air, but lacked a venue. The angry persona and alienated stance of punk rock complimented what was happening upstairs at the CEAC, so when we were approached by Ralph Alfonzo, the manager of the Diodes, in the spring of 1977, about the possibility of using the basement level of the Duncan Street building as a weekly music venue, the idea was given the go-ahead. The Diodes booked the bands and did all the (legal) legwork – ensuring that each weekend there was a party permit in place from the city so beer could be sold. It’s been said that Ralph owned the club; rented the club; that it closed because it lost its liquor license; that it was the scene of ongoing mayhem… all rubbish. The club operated independently from the programming two floors above, but it existed under the umbrella of the CEAC and its corporate parent the KAA. We paid the hydro bills and through Art Communication Edition, promoted the bookings.

As I said earlier, there were at least three collaborations between a couple of the bands and performance pieces we did on the road, including a recording. While the recording was in actuality issue # 8 of Art Communication Edition, the label said Crash ‘n’ Burn Records, so there was a plan to produce future recordings; but that never panned out for some reason. The club was only open one evening per week; either Friday or Saturday night, I don’t recall which. I’d never performed there (although I wanted to start a band that played only the most obnoxious sounding instruments possible). I did, however, shoot a video down there that was screened at The Funnel in December 1978 as part of a New Wave On Film/Video programme. But I’ve never seen it and haven’t a clue where the tape ended up. When Kire Paputts interviewed me for his film The Last Pogo Jumps Again (2013), I sent him to the CEAC Archives at York University and gave him permission to use anything he found by me relating to the Crash ‘n Burn… so if it still exists, it’s there.

Crash ‘n’ Burn, Toronto’s first punk club, was located in the basement of the CEAC and ran from July-August 1977, 15 Duncan Street. Photo by Adam Swica

Now to the $64,000 question: why was it closed down? I think there were two of three factors that led Amerigo to a stupid decision. Freshly back from Kassel, he found himself in the position of becoming what he once had detested, and no amount of rhetoric would change the fact that he had begun his entry into art stardom. (I was hardly as doctrinaire nor as partisan — I liked hanging out with art stars and saw the irony of the situation.) All the nihilist posturing aside, the bands were in search of record deals, and for Amerigo this led to disillusionment. According to Diane Boadway, he thought the bands simply weren’t radical enough. (It’s beyond me how there is any difference between lusting after a record contract or a government grant.) Ultimately, at the end of the day, maybe the decision came down to simple jealousy. It would have been impossible to predict the rapid changes that were to occur within both the funding vehicles and the art world; it would have been prudent in my mind to take the long view and renegotiate the use of the space and transform it into a permanent, and highly profitable, commercial venture. Renovations would have been needed to meet health, fire, and safety codes; but I think the transition would have been fairly smooth. The Royal Alexandra Theatre aside, the building was located in a semi-industrial neighbourhood so noise violations would have been moot. The one problem that would have caused trouble would have been drugs. The Crash ‘n’ Burn was a beer-only venue — there wasn’t even pot (!) — but hard drugs were gradually worming their way into the scene. But whatever would have happened, I think it was a short-sighted mistake. The decision to kill the club was not an isolated stupid decision, but the first in a series of stupid decisions that grew increasingly reckless and destructive. With the challenge to his ego out of the way, he embarked on a course of self-sabotage that not only destroyed the careers of the artists he associated with but killed the centre itself.

There’s one thing I forgot to say about the Crash ‘n’ Burn, and in a funny way gives an idea of the vibe of the place. Mysteriously, at some point over the course of the life of the club, a really bad painting had invited itself to grace the north wall. After the place closed it was found that every single square inch of wall space had been tagged with graffiti — yet this anonymously donated, really bad painting, had remained untouched.

As for my role, this was actually a very difficult and emotional period in my life. I was in a relationship that was imploding and the direction of the Centre was becoming increasingly doctrinaire and reckless. I had made a few super-8 films but felt they weren’t up to snuff enough to screen publicly, with the exception of the documentation of one European performance piece (which I think was shown upstairs) and the video I shot at the Crash ‘n’ Burn. I wasn’t living in the country by that point and so didn’t attend the screening.

Mike: The Canadian Super 8 Distribution Centre found a home at CEAC for a moment, before its dissolution.

Bruce: The Toronto Super 8 Festival ran from 1976-83, and its success led naturally enough to the question of distribution. How could this work be seen and shared? The Canadian Super 8 Distribution Centre was housed at CEAC in 1976. According to its statement of intent the objectives were: “1) Publication of a directory listing both Super 8 filmmakers and Videographers currently working in Canada. 2) To provide the local Toronto Community with regular Screenings of works produced by Independent Super 8 Filmmakers and Videographers. 3) To develop a policy for the practical operation of a Super 8 and Video Distribution Centre. Because of the mutual suitability of Super 8 with Video, we see the Centre offering equal distribution and viewing facilities for both media. Contact will be made with as many Filmmakers and Videographers as possible, asking them for statements about their works and documentation, if possible. The publication of the Directory will enlarge the possibilities of future granting for Super 8 Filmmakers from Government Granting Institutions. Supportive documentation is needed for Individual Granting Programmes to be initiated for Super 8 Filmmakers, (who do not yet qualify for project grants with Canadian institutions supporting the Arts). The Canadian Super 8 Distribution Centre is working toward this aim to improve the situation for Super 8 Filmmakers as well as represent the interests of Videographers. The Directory will exist as major documentation of the growing interest, respect and enthusiasm for Super 8 Film among both Artists and Independent Filmmakers.”(Canadian Super 8 Distribution Catalogue, 1976)

The directors were Janet Sadel, Jennifer Gould, Peter Chapman, Darryl Tonkin, and Ed Radford. For some reason, the distribution center was very short-lived. There had been (I believe) an unrelated falling out between Amerigo and Darryl Tonkin, and I remember an incident involving Janet Sadel, who I believe briefly sat on the board, which amounted to an aborted power grab. (The other names listed here don’t ring a bell.)

Mike: How did CEAC function within the ecology of Toronto’s art community?

Bruce: From the outside one might surmise the existence of an art “community” in Toronto in the late ‘70s, but that was just so much fiction. The environment within which we all operated was one of intense competition, and by 1978 there were KAA, Art Metropole, A Space, Trinity Square Video, and Gallery TPW all vying for the same limited number of government handouts leading to the expected friction. These competitive divisions could be interpreted in any number of ways; from the widely known fact that General Idea lusted after the Duncan Street building, to the downright silly thinking on the part of a Canada Council officer that CEAC’s dislike for A Space sprang from homophobic animus. (I remember being asked by Brenda Wallace, our Canada Council officer, why there was so much hostility between A Space and CEAC. “Is it because they’re gay?” What could I say? “Uh yeah Brenda, you’re so observant, I hate fags.”)

Mike: It is difficult to imagine now that video equipment could be rare or expensive, but in the 1970s it was hard for artists to access. Could you talk about the video equipment at CEAC, and if use restrictions caused community frictions?

Bruce: The Canada Council did receive complaints about “censorship” in relation to the video facilities, but given that the complaints were anonymous not much sleep was lost. According to Dot Tuer’s article, early in 1976 “ [KAA] began the ambitious construction of a video-production studio emphasizing broadcast quality and colour technology.” (Dot Tuer, “‘The CEAC was banned in Canada’: Program Notes for a Tragicomic Opera in Three Acts,” in Mining the Media Archive: Essays on Art, Technology, and Cultural Resistance (Toronto: YYZ Books, 2005) This is incorrect. Up until late 1977 or early 1978, the top floor of Duncan Street was a wide open performance area — easily the largest gallery space in the city. It was a room with two rows of columns running the length of the space and a row of large windows facing west. It wasn’t until after the Crash ‘n’ Burn closed that construction began on building the video production studio using the westerly row of columns as a guide to build a partition wall, with the long narrow space by the windows fitted up as the new office. Prior to that video portapaks were used for documentary production; I don’t remember how many there were (not many I suspect) but they were never lent out.

The Free University-inspired seminars were becoming increasingly esoteric and removed from life on the ground, and after Saul Goldman was brought in to take charge of the new production facility – which gobbled up most of the space — I think the performance artists were elbowed out of the way. Saul Goldman was brought in when CEAC got the broadcast quality video equipment and it’s my guess that the funding bodies made it a requirement for receiving the stuff that there be someone on staff who knew how to properly maintain it. Makes perfectly logical sense. Saul was this really straight guy, in every sense of the word, and was not from the arts community and was not an artist. He was the tech guy and taught a workshop in video editing. I’m speaking for myself here, but would include everyone else in saying that our technical ability was pretty near zero. Diane Boadway recently commented to me “I was just thinking about the video studio and remembered that there was some jealousy from other art groups in town when CEAC scored the equipment. You probably would have remembered that.”

As far as the video studio is concerned, I had dinner with Diane Boadway and Peter Dudar last night and they seemed to agree that the equipment was there for anyone to use. (Diane made, in her words, a sex change tape; and Peter was working with film at the time and used the studio but not the equipment.) We all agreed that it would be good to touch base with Saul Goldman again (assuming he would welcome the contact) to find out what he remembers. After the fall the video equipment moved to a rented space on Front Street and operated as a commercial studio and editing facility, and then into a building on 124 Lisgar Street that was a former Salvation Army church. This building had been purchased in 1980 (with what money is the big mystery) but it was too large, and really was the end of the line. All of this I know only second hand, because I had left the country in October of 1978. As far as the idea of CEAC TV is concerned, I know of no concrete plans, but like the appearance of “Crash ‘n’ Burn Records” (a one-off that implied an active record label), one could extrapolate that such an idea was percolating somewhere in the background. Scoring the video equipment was a long-time goal, the genesis of which dated to that conference in Buenos Aires in late 1975 where, to use Dot Tuer’s words, “artists envisioned the video medium as a tool to diversify the hierarchies of information and media…” (Dot Tuer, “‘The CEAC was banned in Canada’: Program Notes for a Tragicomic Opera in Three Acts,” in Mining the Media Archive: Essays on Art, Technology, and Cultural Resistance (Toronto: YYZ Books, 2005) Sort of like the internet!

The CEAC was nestled in the middle of a decade that began with Leonard Bernstein’s cocktail party to benefit the Black Panthers and ended with the launching of Fuse and Bomb (the magazines). It was also a decade when all accepted tropes were being upended, and an amount of outrageousness was presumed. For example, in 1974 I submitted a grant application to the Canada Council written in Crayola crayon — and I got the money. That would be unthinkable today. It was a time when Council officers were on the artist’s side and would help you get funding, as opposed to the anonymous bureaucrats of today. Yet as the end of the decade began to close, all the new accepted orthodoxies had begun to be denounced, as I had quoted above from Lucy Lippard’s outright rejection of conceptual art.

The entire decade was nothing if not one of constant conflict. Within months in either direction of CEAC’s fall, The Body Politic was facing criminal charges for publishing an article titled “Men Loving Boys Loving Men,” the board of A Space was in revolt and ended in a palace coup, and The Funnel was at loggerheads with the provincial film classification board. Had any of us been able to predict the future we would have been absolutely catatonic over the state of the art world in 2013, let alone the significant changes in focus when conservative regimes took the reins of power throughout the west after 1980. It showed a weakness of mind when arts organizations across the board assumed that government largesse was a) safe b) ongoing and c) hands-off. It bred a kind of myopic laziness that still infects vast swaths of the art world in Canada. Although to be fair, Suber Corley made a concerted effort to woo corporate Canada into financing the avant-garde, but to no avail.

When I said that closing Crash ‘n’ Burn was the first in a series of stupid decisions that grew increasingly reckless and destructive it was because there was a refusal to plan the long game — manoeuver yourself into a position where public funding and the vagaries of government whim would be completely irrelevant — and that would have been a serious possibility had the Crash ‘n’ Burn been reworked as a profit-making operation. Then it would have been possible to do anything. Whether because of laziness, or entitlement, or a misreading of the landscape, there was an assumption that life could carry on as always.

I don’t know how other places operated at the time, but the board was pretty loose — it was neither elected nor was a potential board member expected to bring specialized knowledge or abilities (fundraising, publicity, legal advice) to the table. This is how boards of director operate today. I was on it, Diane Boadway was on it for a time, Darryl Tonkin was a board member in the early days; but at the end of the day it was the Suber and Amerigo Show. Suber wrote the grants and hunted down alternate funding sources (with not much luck — corporate money didn’t flow into the avant-garde then) and Amerigo steered the programming and let’s call it the philosophical direction. I was nominally his assistant.

Mike: The publication changed its name to Strike. Was that significant?

Bruce: Given the nature of the seventies, changing the name of the in-house publication from the bland Art Communication Edition to the more culturally in sync Strike! wasn’t such a big deal, and the first issue under the new moniker carried on as it had in the past.

Despite the typo, Dot Tuer gets it right when she stated that with the name change from Art Communication Edition to Strike in January 1978 “the nature of the polemic between the covers of the magazine, however, did [not] dramatically change at first.” (Dot Tuer, “‘The CEAC was banned in Canada’: Program Notes for a Tragicomic Opera in Three Acts,” in Mining the Media Archive: Essays on Art, Technology, and Cultural Resistance (Toronto: YYZ Books, 2005) It had contributions from many of the artists and thinkers that had been involved with CEAC from the beginning. This was the period during which the CEAC School appeared, directly influenced by Joseph Beuys’ Free International University.

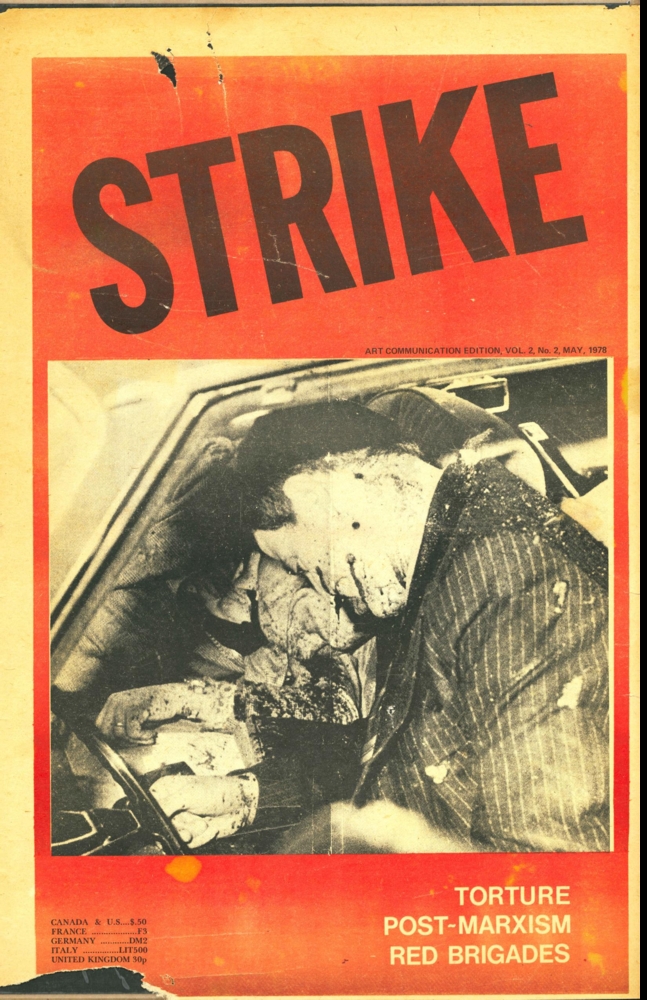

Where the narrative begins to become confused was after the publication of the second issue of Strike. Similar in nature to the graphics work of Beuys’ associate Klaus Staeck, the issue contained transcripts of the absurdly circus-like trial of Red Brigade members and a piece about Central American death squads. The issue would have been put together while the “Five Polemics to the Notion of Anthropology” was in progress and released sometime in late April with a May cover date. The Toronto Sun, then as now, saw red meat in the issue of wasting taxpayer’s dollars; then, as now, the Sun was ignored.

Mike: The second issue of Strike contained an editorial that some read as being sympathetic to the Italian Red Brigades, a terrorist organization who had kidnapped and killed premier Aldo Moro, along with his two bodyguards. The salient paragraph in Strike read: “We are opposed to the dominant tendency of playing idiots, as in the case of punks or the sustainers of the commodity system. The questioning of thorough polemics of the cultural, economic and political hegemony should be fought on all fronts. To still maintain tolerance towards the servants of the State is to preserve the status-quo of Liberalism. In the manner of the Brigades, we support leg shooting/knee capping to accelerate the demise of the old system. Despite what the ‘new philosophers’ tell us about the end of ideology, the war is before and beneath us.” (“Playing Idiots, Plain Hideous,” by Amerigo Marras, Suber Corley, Bruce Eves, Paul McLelland. STRIKE, May, 1978) The Toronto Sun ran a headline that read: “Ont. Grant Supports Red Brigades Ideology: Our Taxes and Blood-Thirsty Radicals.” Though any full reading of the article quickly plunges the reader into a labyrinth of Marxist arm-twist manoevres and abstract theorizing, so it can be hard to tell exactly what is being supported.

Bruce: What is interesting far after the fact about the two quotes from the “Strike collective” is the number of bridges being burned in such a short stretch of rhetoric. The “new philosophers” jab is clearly a reference to Bernard-Henri Levy, and possibly Joseph Beuys, who were mere months prior to this being fawned over; and the “playing idiots” I can only assume to mean the punk rockers/art students, Reindeer Werk, and Ron Gillespie – artists that we in the collective (he said sarcastically) had long, warm, and productive relationships with.

You are correct in your reading of the editorial in question as “so filled with Marxist arm-twist manoeuvres and abstract theorizing, it can be hard to tell exactly what is being supported” because it’s just so much radical-chic posturing. As I recall everything carried on as usual, at the beginning, given that it was, after all, the Toronto Sun that broke the story; however, that changed when all the other media outlets piled on. There was a firestorm in the press over the next two weeks. Looked at in retrospect, the statement to the press was full of weasel words that I flatly reject as being nothing less than a macho pissing contest. The statement I find to be full of “weasel words” contends that “we do not believe that terrorism makes any sense in the context here and we question the theoretical basis of any vanguard group that intends to lead or speak for the people…” [italics added]. (Statement to the press by Strike Collective, May 12, 1978) Terrorism is acceptable anywhere else that doesn’t have funding from the Canada Council? I don’t think so. This is just so much radical-chic armchair horseshit. Exactly the kind of nonsensical rhetoric that in another context prompted Lucy Lippard to admonish herself and her conceptual art peers as being “so totally enveloped in the middle class approach to everything we did and saw, we couldn’t perceive how that pseudo-academic narrative piece or that art-world oriented action in the street were deprived of any revolutionary content by the fact that it was usually incompressible and alienating to the people ‘out there,’ no matter how fashionably downwardly mobile it might be in the art world.” (The Pink Glass Swan: Upward and Downward Mobility in the Art World by Lucy Lippard, Heresies #1 Feminism Art Politics, 1977)

The statement goes on to say that the materials published in that contentious issue of Strike was, in essence, a matter of correcting media bias. How noble. As far as I know the text was written by Amerigo and Roy Pelletier. Roy, an architect, along with Paul McLellen and Bob Reid (a friend of Roy’s) were the new arrivals to the Strike collective and I’d venture to say the situation would have been different without their influence.

Unlike the Contextual Art conference (which looked like a down-market United Nations General Assembly meeting taking up the entire floor), the later meetings were held around a conference table in the library. If I may act as a dime-store armchair psychologist, Amerigo was daunted by the prospect of art world success, and fear of success can prompt self-sabotage. When the scandal broke, a sensible, media-savvy person might have offered a retraction and some lame excuse and weather the storm, knowing it would die down eventually; Amerigo took the media bait and got argumentative. The attempt at trying to justify the offending issue by comparing himself to the Futurists only made the situation worse. Much of the blame can be laid on the shoulders of the board because of its passive acquiescence to Amerigo’s wishes. In the real world he would have been given two choices: fall on your sword to save the organization or be fired.

By the end of May the issue had reached the floor of the House of Commons as a means for the Conservatives to politicize cultural funding and embarrass the government. What’s curious about the entire affair is that there was another European tour in the midst of all of this. In retrospect, the scandal mustn’t have felt very threatening at the time otherwise the appearance at the ArteFiera in Bologna in early June followed by a couple of gigs in Zagreb would have been cancelled.

For me, the magnitude of the events hit home when we got to Italy with copies of the paper. The organizer of the art fair in Bologna, Arturo Schwartz, who had always been very warm with us, was furious! He threw the papers to the floor and was hollering in Italian. (However, he later collaborated in a performance at the art museum in Bologna). When we got back to Toronto we found people crossing the street to avoid contact with us. There were no meetings with anyone. Everyone was trying to protect their own turf. It was a wise move not to call a press conference for the simple reason that it would have turned into a zoo. A statement was released and individual interviews were granted to Olivia Ward from the Toronto Star and Robert Fulford from (I think) Saturday Night magazine. Amerigo did a taped interview with (I think) CTV in the production studio. That was all. We were so toxic that it was presumed any contact would have been a threat to someone’s funding. General Idea tried to grab the building, assuming (wrongly) that it belonged to the government. There was a letter written in June, published in Only Paper Today, signed by a group of people I’ve never heard of, claimed that we were preparing for long-term revolutionary work by attending international art fairs. The Only Paper Today was allied with A Space (if not actually published by) and so was in a bit of conflict of interest. However, another from the Fine Arts Department at York University, in the course of condemning us, denounces the art community’s silence and unwillingness to take a stand on art or politics – which allowed the Councils to act unilaterally.

There was a motion put forward by a Conservative MP in a semi-rural riding authorizing the government to interfere with the Canada Council. This was voted down and the House of Commons moved on to more pressing matters. Had there been political interference from the government into the operations of an autonomous, arms-length funding agency that would have been a scandal. As far as I know, there is no smoking gun. The CEAC was, however, visited by a couple of Mounties; this I assume was undertaken independently of the government given the enormous amount of media coverage the issue had received, and I am fairly certain that the phones both at Duncan Street and my parent’s house had been under surveillance, at least for a brief period of time.

The funding cut off was completely unilateral and abrupt. The Canada Council cut off came on July 4th and the Ontario Arts Council on July 10th. There was no peer-review process, it was immediate. Needless to say, we were mortified by the Councils’ decisions, but there was some debate as to whether it was simply too late to mollify them. They were watching out for their own necks as well. There appears to have been only one letter to the Ontario Arts Council expressing astonishment that anyone would take allegations made by the Toronto Sun seriously. There were no protests from the “art community” because there is no such thing as an “art community,” merely a group of individuals and groups working in similar areas scrambling for the same government handouts. There was fear for their own funding as well as lust for the goodies the CEAC was able to acquire.

It was with the second issue of Strike that the break happened. And with the break came a change in attitude. Peter Dudar said that the place was suddenly remote and closed off, the inner sanctum of the office was off limits and a casual drop-in discouraged. His description sounds like another trope sort of unique to the 1970s — cults. The previous ironic acknowledgement of speaking from a privileged position within an art world had disappeared along with all sense of style. It was like a type of madness had infected the place. As the attached flyer for a couple of gigs on Zagreb indicate, CEAC and Strike were by then one in the same.

But what is peculiar about this period is that while there was the appearance of remoteness, I recall a trip to New York to scout real estate to open a branch plant. The endeavour was abandoned when it became clear that even then Manhattan real estate didn’t come cheap. I may be in error about the timing of this trip, but I think it was in the Spring of the following year, just before the shit hit the fan. The exact chain of events is a little difficult to sort out, partly because everything happened very rapidly and partly because I was out of the picture by July and out of the country by November. I’d gotten a job in Newmarket with the Post Office working the night shift; Amerigo got himself hired as a translator by the Italian consulate on Dundas Street but was fired when they figured out who he was; Suber continued working in IT. With zero support and zero income the place was a doom factory. I don’t think they were able to hold on at Duncan Street for very long before defaulting on the mortgage, but maybe you should talk to Diane or Peter about that. As an aside, yesterday’s obituaries for Peter Worthington, founder of the Toronto Sun and its editor-in-chief throughout the 1970’s, depicted a man virtually at war with Pierre Trudeau, Canada’s former Prime Minister. It makes one wonder whether the scandal surrounding Strike was nothing more than a convenient way to attack and embarrass the editor’s bête noir?

After Duncan Street was lost the CEAC was dead and the name was never used again. There was a temporary video production facility set up on Front Street and then an attempted revival on Lisgar Street. I visited Lisgar Street in 1980/81 and the place was a white elephant. For this you should speak to John Faichney as he was involved in the relocation. If you can get to Soaul Goldman, he will know all the details. After the move to New York, Amerigo was again scouting around for real estate hoping to replicate CEAC. The first building to attract his attention was the building now housing the Anthology Film Archives on Second Avenue and 3rd Street; followed by a mansion-sized brownstone on Second Avenue and 14th Street; and then a defrocked synagogue owned by the city on Houston Street. Nothing came of any of these.