Ron: At CEAC (Centre for Experimental Art and Communication) we tried to make openings for as many people as we could. Amerigo Marras was a little conservative around bodies and nudity. He feared arrest, being told you’ve got to go and stay overnight. So he held onto this censorship, he was a Marxist, but he had this censorship that he didn’t want to go past. There were a lot of contradictions going on with Marxist understandings of the body. To me the Marxists were just as conservative as others on the left. They saw women as objects and I totally disagree with that.

Mike: How did you meet Amerigo Marras?

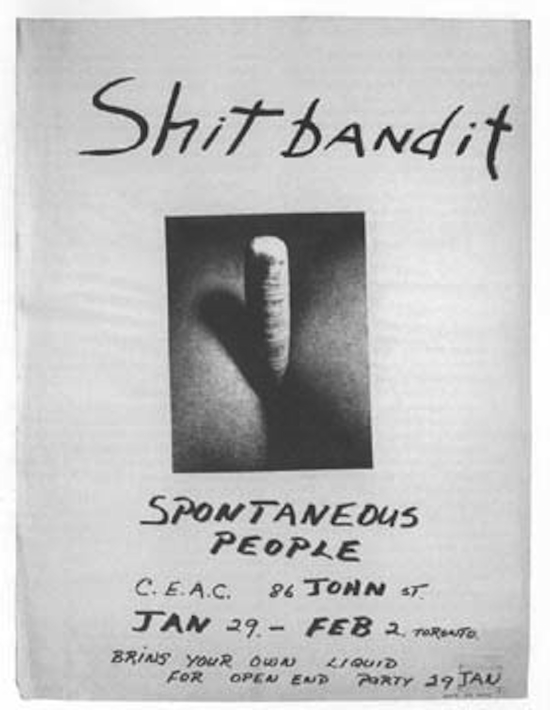

Ron: I met Amerigo through Bruce Eves, who I went to art school with. Bruce was part of Shitbandit (a group of artists formed at the Ontario College of Art). Bruce told Amerigo about me and what I’d been doing. I went to see him at Kensington Arts Association, when he was over on 4 Kensington and then I saw him again over on John Street (after KAA became CEAC and moved to John Street) when we were going to do a performance. I remember this little wee guy coming down the stairs. “You must be Ron Gillespie.” “Yeah, yeah.” “Well what do you do?” “I do dust, I’m into dust.” He sort of looked at me. “Yeah I blow up things.” Right away something clicked and I knew that this guy was very heady. From there it just took off.

Mike: Did you feel like you were part of a CEAC group?

Ron: CEAC started to become more of a cohesive unit, though it was always made up of individuals. The guys going there and the girls who came with us. Of course I was very wild. The Crash ‘n’ Burn (punk club) opened in the basement of CEAC. Teenage Head, Nazi Dog, the Diodes, it was all coming. Amerigo and the others were trying to be as exciting as possible, and they were. They were all in their twenties. I was probably the oldest one, I was 29. And of course I had lived in Africa for a year and a half. That was still pretty fresh, it was a big subject.

Mike: Do you think they were revolutionaries?

Ron: No, the idiot Mao Zedong was a revolutionary. But to me he was just a fucking asshole because of his persecution of the Tibetans. I was studying science with Veronica Loranger, we were looking at the most recent scientific discoveries about stem cells. We were looking at the whole body and especially developmental theory. Developmental biology was on the cusp, extremely important. Many artists thought science was fascism, but sure enough, twenty-five years later, developmental biology is at the forefront of science and philosophy. We were just kids then looking at biology and socio-biology. The study of the ants and the kingdoms of all the animals and plants that were being destroyed. For the Marxists it was all capitalism, I said no it’s religion as well. People have been farming a certain way for four or five hundred years. Suddenly they’re told you have to increase your yield. They go to the geneticist. You start having gene manipulations of flowers, so that flowers will produce more pollen for the rest of the insects. A lot of science was quite radical.

Mike: Did you talk to Amerigo about these ideas?

Ron: Amerigo and I would sit down and have a good discussion. He didn’t like science so that was always a tension, especially later on. But the last time I saw him he said, “Uncle Ron I’m getting interested in science.” I didn’t see him after that. I went with Bruce (Eves) and John (Hammond) idea wise. Bruce and John cared about the diagnosis of schizophrenia I carried. Amerigo saw that as a result of capitalism. The support structures around mental illness basically used the same ideas as the 1950s, there wasn’t much change. Shock treatment was still going on in 1975. Even today, I’m not sure if it’s totally wiped out. Going up against the medical world and trying to stay positive was really hard to do. We weren’t a revolutionary group at CEAC. That was not the idea, though Amerigo might have thought we were. I was not really into that. For me revolution was more important in the nineteenth century with the beginning of the industrial world, the trains and the burning of fossil fuels, the destruction of the Amazon jungles and the mining in Africa, people coming to strip the land.

Mike: What was the project of CEAC?

Ron: Communication. Communication of ideas that would be used for the film and video world. The gallery became an archive of submissions, books, texts, themes, cartoons. They had all this material coming in with the word processors running 24 hours a day.

Mike: Was CEAC’s communication aimed mainly at other artists?

Ron: We were interested in other artists coming in but Amerigo wanted to control the research flow, he always wanted to be mentioned. He had trouble with people coming in and using the archives, he wanted to know what they were going to use it for. That’s why some people got the idea that it’s a CEAC archive and it’s not for us. That was definitely a problem. Even the stuff we were showing that wound up in the archives, there was a lot of raw work going on in there. I was more interested in letting it go, opening it up and not blocking access.

Amerigo became his own nemesis because he was applying for grants all the time, he was always looking for money for what we were doing. The Canada Council was quite worried about the material at CEAC getting into the newspapers and of course that’s exactly what happened. The Toronto Sun closed down CEAC.

Amerigo refused to cater to the dominant system. The system was the arts councils. He was trying to hold onto the grant world so ideas could travel and so that he could maintain the huge expense of communicating that CEAC represented.

Mike: Some artists felt that CEAC was not accessible, that the video studio for instance was not open to them. Do you think those complaints were fair?

Ron: That was absolutely true. Amerigo was a Marxist conservative. The Marxists were always talking about access, but when it came to their own access, it wasn’t granted. There were a lot of contradictions. I was getting ready to break from the mold they were trying to bring about. I was the only one that was interested in Darwin and what was going on with the body and society.

We did a CEAC show in Detroit that almost caused a riot. We were getting known by the violence, now it’s not a big deal but this was back in the seventies.

Mike: Can you tell me about the performance you did at Documenta 6 (1977)?

Ron: That was the anti-celebrity performance where I invited a harmonica player from the streets. He was hanging around Documenta trying to make some money. I asked him in English and he spoke incredible English. He was a street person. Having driven a taxi I knew street people, there’s one thing they all have in common. If you have money they’ll do anything you want. I talked to him about a performance and he said sure, no trouble.

I was the first one (of the CEAC group) on. I got up to the blackboard and drew a circle and wrote out six famous artist’s names on the wheel. An homage to Duchamp. Joseph Beuys was there. I had the harmonica player come in and he played Lili Marleen. That lasted two or three minutes. I gave a little bit of a speech and that was it. They took some pictures and I just wanted to get out of there. I could feel this overwhelming anxiety,

Documenta felt out of proportion to what was really going on. There was a lot of beautiful work there, but it was the end of being a non-profit artist. There were all these famous people, I thought this is more like a “who you know” type of thing. You have to know the right people. I had to get away so I got on the train, I had a rail pass and went south to Lecce in Italy where I met the genetic artist Franco Gelli. I was into genetic art big time because of Veronica. I think I was there for about four hours. I just had enough time to get there, spend the afternoon, then catch the train and go all the way back to Dusseldorf. It was nuts but that was the anxiety, I was so stressed out and tired.

Bruce Eves could tell you what happened at Documenta, he was more together than all of us. Amerigo was off on his Marxist thing. I was getting to the point where I had to make up my mind whether to cross the line and go join a gallery or see if I could even get a gallery that would be interested in my work. There were so many questions. That was the last real thing I did in the art world. From then on I didn’t care. I was not interested. I would do the odd photograph. I did some writing, but basically Documenta led to going right over.

After I got back I started gradually withdrawing and didn’t want to talk to people. I didn’t want to go back to the art world after 1978. What I saw going down in the art world was that a lot of people knew what they were doing, but you had to know the right people. And that was really hard because I had very little experience.

Mike: How did you wind up in The Clarke Institute?

Ron: I was living over on Robert Street, and Veronica was at work. I went totally paranoid. That was it. That was the beginning of the post-1978 world. If you could afford good doctors you might be OK. I probably should not have had to go to a hospital. If I’d had a good doctor that wouldn’t have happened. The attendants came in with a big needle of chlorpromazine. That was pretty provocative because that was the suicide drug, and lithium was the other one. I was there four weeks.

Mike: Did they try to do electroshock?

Ron: They asked me about it and I said no, I’m not interested. I had enough background to know that chlorpromazine was a really provocative drug. If you went out in the sun, it burned your face. That was one of the side effects. They give you a big needle and then you become a zombie. You can hardly do anything.

Mike: Were you medicated the entire time you were in the hospital?

Ron: Yeah, yeah. There was a warrant they could get you to sign so you wouldn’t leave. There were certain requirements before you could leave but I wouldn’t play psychiatrist games. I had thirty breakdowns mainly because I received the wrong diagnosis. I had the wrong medication, so I kept getting sick. Finally they got me on the bipolar medicine. Touch wood I’ve been OK for twelve years, I haven’t had to see a psychiatrist. That was very much a strait jacket.

My work completely changed after CEAC collapsed in the spring/summer of 1978. Amerigo, Bruce Eves, Suber Corley and Paul McLellan went down to New York in 1978. The boys were all in New York by then. I was still here with Peter Dudar and Lily Eng and John Faichney and we tried to make a go of CEAC but it was impossible. When CEAC closed the doors on Duncan Street and sold the building, they put down a mortgage on this place on Lisgar Street. Then Xerox wanted $4000 for unpaid fees from a machine we had rented on Duncan Street. We couldn’t afford the building insurance, the boiler room, the Xerox debt, we were screwed. There was no future at all for what we were doing. Then we went our own way.

Mike: Were you surprised there was no support in the art community?

Ron: We didn’t expect support from anyone. The older artists, the Carmen Lamanna artists, were probably anti-CEAC. There was a “Thank god it’s over” feeling.

Mike: Who were the Carmen Lamanna artists?

Ron: John Scott, Joanne Todd, Karl Beveridge and Carole Conde, General Idea. I don’t know if General Idea ever came to any shows we did. But there was also the A Space crowd.

Mike: Were there tensions between A Space and CEAC?

Ron: Yes, we had so much. We did all these performance art trips to Europe and we were inviting artists from all over Europe to come to CEAC. Other organizations looked at us as not only as competition, but we had created a whole new game. All the artists from the alternative galleries that were working at OCA (Ontario College of Art) were against us. It was quite a split, there are people today who still won’t talk to me. Bruce called it provincialism

Mike: In 1984 Clive Robertson’s “Talking: A Habit” lecture “Rhetoric on the Run” was published in Parallelogramme. Clive said that CEAC’s only legacy was to host the punk club Crash ‘n’ Burn. I guess reading it was upsetting so you went to visit the mag’s offices where you met up with ANNPAC manager Ric Amis.

Ron: We had a fight and Ric threw me down the stairs. He called me a terrorist. I went over and tried to talk about what was going on, and we started wrestling. It was funny because he was so strong and here I am, a little wee guy, a cab driver who smokes his brains out and drinks tons of coffee. That was very funny. That’s when I realized there are people taking us very seriously. Here I am, all my friends are gay, my girlfriend, I don’t know what she was. She just went along with everything, we did our thing. Ric Amis. I saw him recently, he’s older and more mature now, beginning to see the light.

Mike: Did you meet Dot Tuer in those years?

Ron: We met around 1984-85. She was the manager of the ex-psych meetings we held every Tuesday night. We played sports and held dances. John Porter would bring in his films. We had a very successful group. Some nights a hundred people would show up. It became so exciting that people were coming to ask us: how did you do it? We can only get four or five people to come out. We were offering a whole other approach. That was one thing about the art world, at least I knew a few people who would come and help out.

Eventually I brought three mental patients to perform at St. Marks Theatre in New York. Amerigo had invited me, he was beginning to see what I was doing with the ex-psychs. For him it was socialism, for me it was just surviving.

It was basically a written performance. We were all reading texts I had written in the last ten years. I was reciting, along with Sheila Gostick, Ana Gruda, Warren Moore and one other person.

Mike: Were there actions?

Ron: No, we stayed within what we could do. These kids had never been on a stage before. They wondered what they were going to do. I’m so excited I’m going to go crazy. All of this would come out. Then they would go onstage and just do it. I always went first so they would follow General Giii. It was heartbreaking, and on the other end of it, they’d never done anything like it. We were bringing in a model for integration and describing people being happy and excited. I’ll still meet them, there’s a few still around, and the only thing we talk about is New York. How are you doing Uncle Ron? What’s going on in New York? The mental health world and the art world should have come together a long time ago. Especially performance art, there’s a lot you can do there.

Mike: What was Amerigo doing when you were in New York?

Ron: He and Suber bought two houses for $17,000 each and they were fixing them up. It was all done by hand. I helped them out when I was there, gyprocking and a little bit of carpentry.

Mike: Was the idea to remake CEAC in New York?

Ron: Amerigo didn’t want to open a gallery. He probably didn’t want to go through all that again. He was younger than me, so all I could think was: you’ve got $175,000. The money thing was screwy. I realized the sonofabitch could have helped CEAC, he had the money. Bruce and John were getting more and more angry at Amerigo who was bitter and angry himself. He would enjoy it when I came down, we’d talk and go to the bars and have a drink. I think he felt he lost the war and he wasn’t ready to start over again. It could have been interesting. He did open a bookstore across the street from CBGB but it was all Marxist literature so it didn’t last long.

Mike: What was Suber Corley’s role?

Ron: Suber had the money, he was always working full time. I only talked to him when we had a board of directors meeting.

Mike: Were you on the board of directors?

Ron: No, I didn’t want to go that route.

For three or four months Toronto was ahead of New York, we had the edge in 1977. That was one of the reasons CEAC created a lot of animosity, people were starting to see biology and Marxism and evolution, when all they knew how to do was paint a picture or draw a body. That used to be enough, but then performance art came along. Look at Marina Abramovic right now, that’s all the kids want to do, they want to do performance. But if you mentioned it in the seventies people shook their heads. You had to have pictures, you had to make photographs.

Mike: Did your performances get videotaped?

Ron: Mostly not. But I have a few tapes on an old format. I haven’t checked on that for a while. The work we did at the St. Patrick studio was provocative stuff. We loved to do it, that was the other thing, we weren’t selling anything. There was no gallery that would buy or sell anything. The strange thing is that a couple of weeks ago I told Paul Petro that I was leaving his gallery. I sent him an email saying thanks for the memories and it was lots of fun. Signed General Giii. That was that. I have to deal with that when the weather is better and I get some stuff back.

Mike: Are you going to another gallery?

Ron: I’m going to take off a year, maybe two. Right now I want to stand back and take a look at what might be down the road. I don’t know if I’m going to get anything much better. I just finished 300 drawings two or three months ago. That’s about the end of the line for me. I don’t know how much I’ll do down the road. But I’m really interested in doing little books, developing that area. I’d like to do an ebook. In March we’ll get down to the Armoury Show. See the New York crowd and what they’re up to.