from left: Jearld Moldenhauer, Joey, Amerigo Marras, Donald Suber Corley. Aug. 20, 1972. First Gay Picnic, Hanlan’s Point. Picture by Charlie Dobie

Time Passes: an interview with Suber Corley (February 2015)

Suber: I’m sorry that I have not gotten back to you. Time passes so quickly. You have really gotten some good information from the best contacts already based upon the information that you shared. The artists who were around KAA (Kensington Arts Association) and CEAC (Centre for Experimental Art and Communication) are much better representatives that I could ever be. The best that I can do is share my recollections at having been at the heart of things, but I was really the person who helped Amerigo execute the ideas that he and others shared.

Mike: You came to Canada as a draft dodger didn’t you? Was it easy to cross the border? Did you come alone?

Suber: I spent the better part of 1968 in New York after leaving graduate school early. I guess the draft board was pretty efficient and by the fall of that year I had been notified that I needed to go to the draft induction center in Manhattan for a physical exam. I don’t remember actually receiving the notice to report for induction, but I knew that I was completely opposed to the war and could not participate. I took a train to Toronto. The border crossing into Canada was very smooth. The Canadian border officials quickly understood what I was doing and helped me to understand the process that I needed to follow to gain landed immigrant status. Yes, I did this alone which was pretty brave of me. I’m not the type to be alone or travel alone. It was the determination to get away from the war and the US government that drove me.

I arrived in Toronto from the States in late 1968, and almost immediately headed north and spent the last half of the school year teaching high school in Hearst, Ontario, before moving back to Ottawa. A family of Quakers had “adopted” me shortly after my Canadian adventure began and I stayed with them for a while before setting up my own living arrangements.

I don’t remember the details around my connection to the “underground railway” but I vaguely recall that there was a group in Toronto that helped make the connection with the Quaker family in Ottawa. I applied for and got a job teaching in Hearst just a few weeks after I arrived in Toronto. Of course, I needed legal status to actually work and I took my job offer to Ottawa where the Quakers helped me through the process. Amazingly, the government in Canada was also very instrumental in my successful transition. My working papers were issued the same day that I applied and I returned to Hearst as a fully landed immigrant.

Before I decided to dodge the draft, I had not been involved with any political movements. I just knew that I had big issues with the way that things were moving. In my last semester at university, one of my roommates and I organized our own protest when Barry Goldwater (a big Republican and candidate for president in 1968) came to our campus. This being the south (where the war and Republicans were popular) it was a scandal that my professors became aware of. They cautioned us about our activities and certainly didn’t support us. When I got to Canada, I did not become involved with any of the various groups that were protesting or supporting draft dodgers. But no one ever expressed any negative comments about my actions until I was called into a meeting with the RCMP in Ottawa after I moved there from Hearst in the summer of 1969. The RCMP, of course, supported their cohorts in the FBI and strongly suggested that I return to the US. Other than that suggestion, however, I never heard from them again. Of course opposition to the war was widespread and did foster a broad political movement that was opposed to the status quo and to repressions of various kinds that existed (and still exist) in the US. At the same time, I don’t think that the gay liberation movement was specifically attached to the anti-war movement. My memories were that broad cultural revolts seemed to be everywhere.

I returned to Toronto to get a second bachelor’s degree in 1970 and moved into Rochdale College. By the time that I got there, Rochdale was a failed social experiment in community living. Rochdale was adjacent to the University of Toronto campus. While it was not officially affiliated with the University, it was in the same cultural space. The meeting between Amerigo and I took place outside on the University grounds. It was pure accident. As I recall, it was very early in the fall as the school year began. I was studying education at U of T and just wandering through the campus when we ran across each other and had a conversation that revealed our common interests.

He shared my Rochdale space and created a life size, reclining portrait of me on the wall in the bedroom. Amerigo’s medium of choice was oil. The portrait was done directly onto the wall above one of the beds in my Rochdale “apartment.” Portraits seemed to have been his primary artistic expression. His art training was in Florence, I believe, though I don’t think that the emphasis was so much on creating as it was on studying art.

We moved out of Rochdale and into an apartment that we shared with Jearld Moldenhauer. The first meeting or two of the Body Politic was held in that apartment. We also used that apartment as the base for a timid gay march that we did in 1971. I remember a total of about six people were in the procession, though I don’t remember where we marched.

In late 1970 I (Jearld Moldenhauer) moved in with Amerigo Marras and Donald Suber Corley (pictured here), into their 65 Kendal Avenue apartment. It is this address that served as both the initial home for Glad Day Bookshop and The Body Politic. Amerigo’s artwork adorned several pages of the first issues of the The Body Politic. Don and Amerigo bought a house at 4 Kensington Avenue in the Market area and allowed the early gay movement to use a shed behind the house as a separate space for both The Body Politic and Glad Day Bookshop. (Photo by Jearld Moldenhauer from www.jearldmoldenhauer.com)

Mike: Like you, Jearld was also an American. He was drafted, and then the American Selective Service System deemed him 4F so he wasn’t compelled to serve, but nonetheless decided to head north to Canada. I’m wondering if there were divisions or hierarchies that were made because of people’s different draft status (some were drafted and fled, some fled before being drafted, some served)?

Suber: I remember a very egalitarian group. The Body Politic, for example, was organized as a collective. To my knowledge, no one cared about anyone’s draft status or even their country of origin. By the way I could have been classified as 4F as well, but I declined. Basically 4F was a classification that you were given if you openly admitted that you were gay. To me, it was a cop-out within my personal set of ethics, but I would never have judged anyone who chose to use this as their way out of the draft.

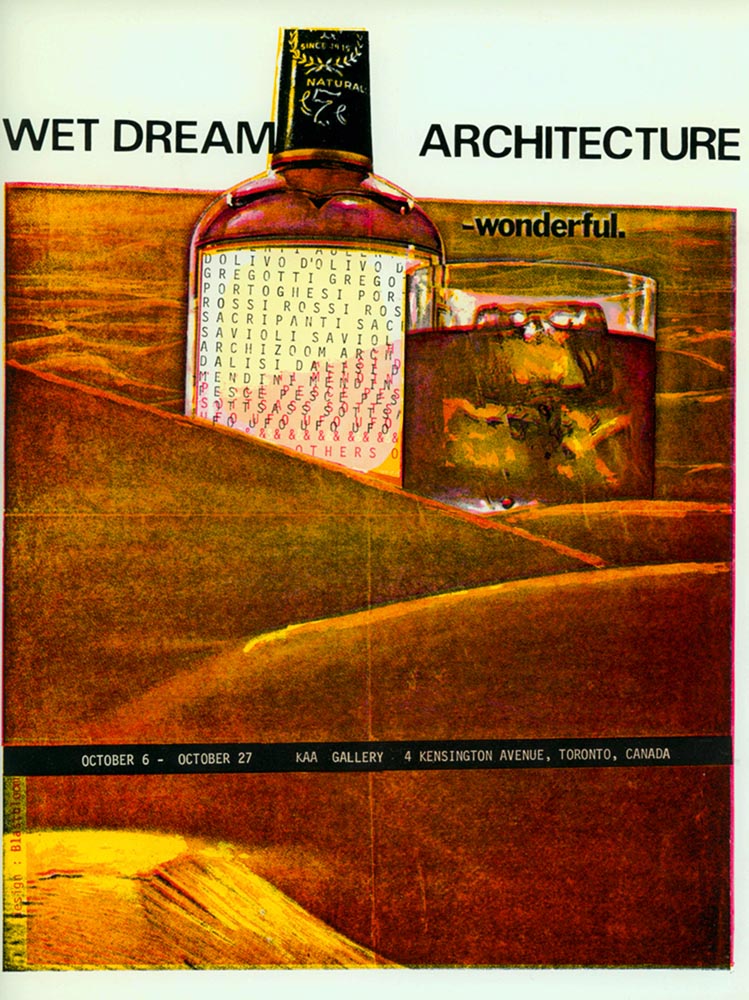

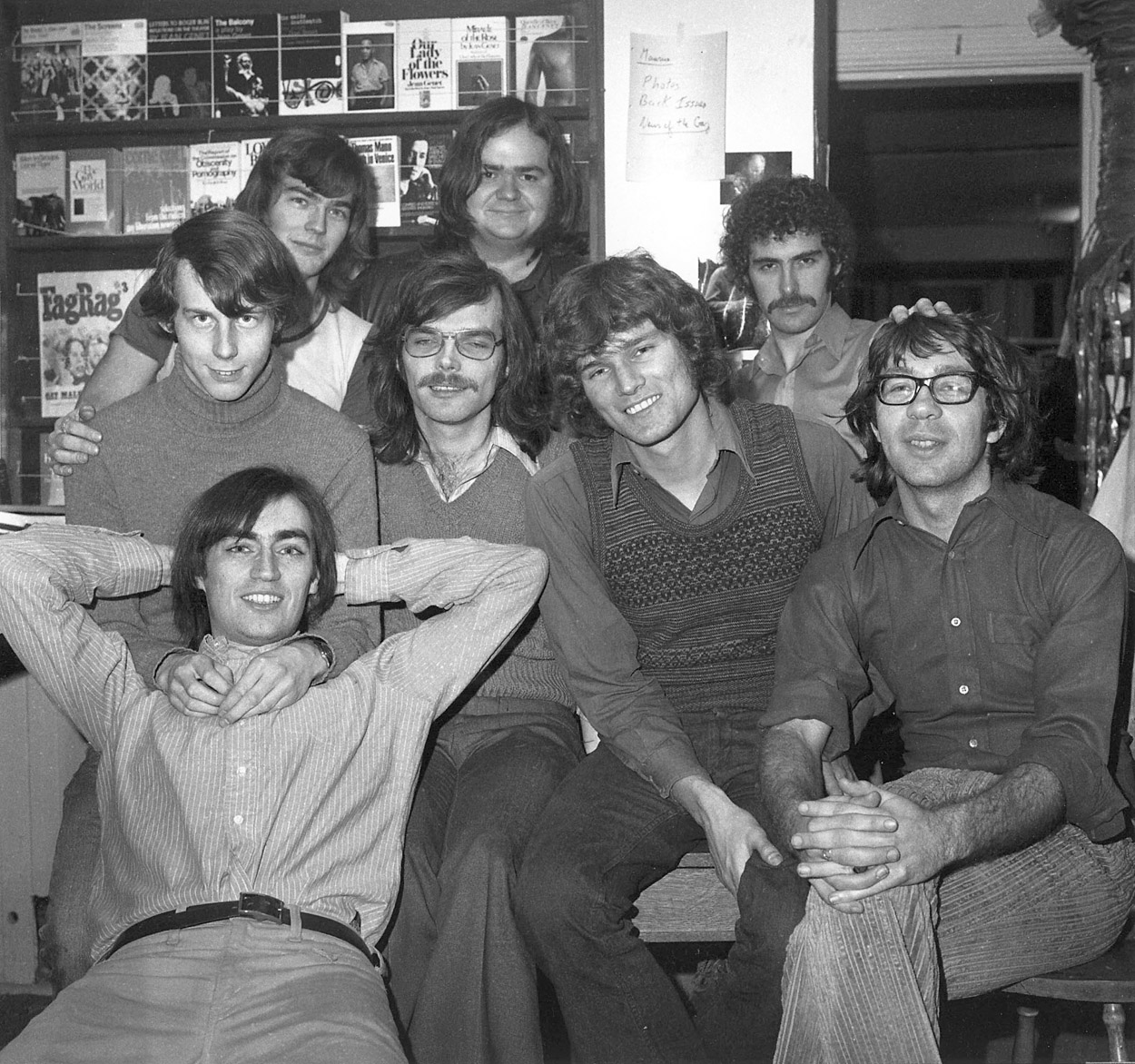

The Body Politic collective in 1972 in the shed at 4 Kensington Avenue (Photo by Jearld Moldenhauer from www.jearldmoldenhauer.com)

From that apartment, the three of us (Amerigo, Jearld and I) bought and moved into 4 Kensington Avenue. When we took over the Kensington Market house, we gutted much of the first floor to create a single large exhibition space. We also renovated much of the second floor. In an early experiment with reconfigurable spaces, the kitchen sink was made movable. It could slip back into its natural corner or be pulled into the center of the room for convenience in preparation and cleaning. On the first floor, we expanded the light coming into the space by expanding windows and installing fixed glass into them. I remember that one of the side windows became a full height, center pivoting window. All of this was interesting design, but I shudder to think about the execution. We did not have access to skilled craftsmen and a large budget would have slowed down the expression that we wanted to get out into public view.

I’m not sure that any of us considered this to be a collective living arrangement. We did much of the joint living out of expediency more than anything else. What I do remember is that our shared views on sexuality were radically different than what came in the following generations. It was considered bigoted to reject someone’s advances based upon their looks alone, for example. Traditional monogamy was also rejected as being an expression of the old regime. So, in some sense, there was a collective sense about our bodies. They were to be shared easily and openly. By this I mean that relationships were not expected to be necessarily exclusive. The relationship between Amerigo and I evolved over the first year into a more traditional model, however. By the time that we moved to Kensington Market, we were a conventional, dedicated couple.

Amerigo and I shared the concept for Kensington Arts Association and built it pretty much alone. Jearld was totally focused on gay politics, the Body Politic newspaper and his bookstore “Glad Day.” We supported Jearld with his work and participated in the paper and store as much as we could. That was on a personal level and totally separate from our intention of building KAA (Kensington Arts Association). While Amerigo and I were influenced by the gay liberation movement in Toronto, we did not end up participating in the way that we might have wished. I don’t want to suggest that I am so negative, but I feel that we got little support from the gay community for our KAA work. The only notoriously gay artist at KAA was Darryl Tonkin. At the same time, the KAA crowd was largely straight and they had little interest or intention towards the gay community. Amerigo and I had one foot in each world and not much support from either.

That’s probably why we scuttled KAA so quickly. While he was not really business minded, Amerigo had a great eye for potential and a great vision for what could be. We disavowed the personal accrual of wealth and hoped for a more socialist-minded world. However, we knew how to take advantage of opportunities as they arose.

Looking back at your question about gay liberation and the direction for KAA. I think that we were interested in a lot of the things that you mentioned, though we never acted on most of those interests. If those were initial directions, the innocence that we had prior to CEAC did not last. Global politics were overwhelming and Toronto didn’t seem to be ready for what was coming.

Jane Jacobs was a friend during our KAA days. However, she was not our benefactor. We would never have thought to consider her in that way. We just liked her. She had a great family. I shared draft dodger status with one of her sons. She was a great cook. And we were positively provoked by her writings. Amerigo had graduated in architecture from the University of Toronto but I think that he was more influenced by Jane than by the school experience. During the KAA days, you can see that influence in the relationship that we built with Yona Friedman, the French architect. Yona was an urban design theoretician. KAA hosted an exhibition of his work. Like the contextual work from Beth Learn, this was a precursor to the ideas behind CEAC.

Other than Darryl and Bruce Eves, much of the art that KAA exhibited was really, really boring. A lot of abstract expressionist, Jackson Pollock wannabees and a few conceptual artists who seemed to be more self absorbed than anything else. Peter White and Dot ? were representatives of the straight, white, art school artist. Beth Lerner and her husband were examples of the conceptual artist crowd. I believe that Ron Giii and Ross McLaren came along about this time as well, but I don’t remember their work being part of the KAA experience. It’s been a long time and the quick moves that we made from Kensington to John Street to Duncan Street pull a lot of memories together. The early exhibitors at KAA came out of the Ontario College of Art, as did much of the CEAC crowd.

Mike: Was KAA an extension of Amerigo’s interest in painting and art, and was CEAC an extension of his interest in moving beyond the gallery walls?

Suber: I don’t think that KAA began as extension of his art. I think that KAA was the sole expression of his art. He had pretty much given up on painting by the time that we moved out of the apartment. As I mentioned earlier, there was some conceptual/contextual art done at KAA, but the space was not large enough to handle non-gallery forms. We had thought about re-building the house into something larger, and even had plans approved by the city, but could not come up with the funding to make it happen. It included radically changing the use of the building and making it exclusively a space for art and architecture. It is true that Amerigo was intrigued with using spaces in multiple ways — having them be transfigurable from one use into another use through movement of building components. You can see this sort of expression in the micro-environment spaces that are being designed today.

Mike: How did KAA turn into CEAC?

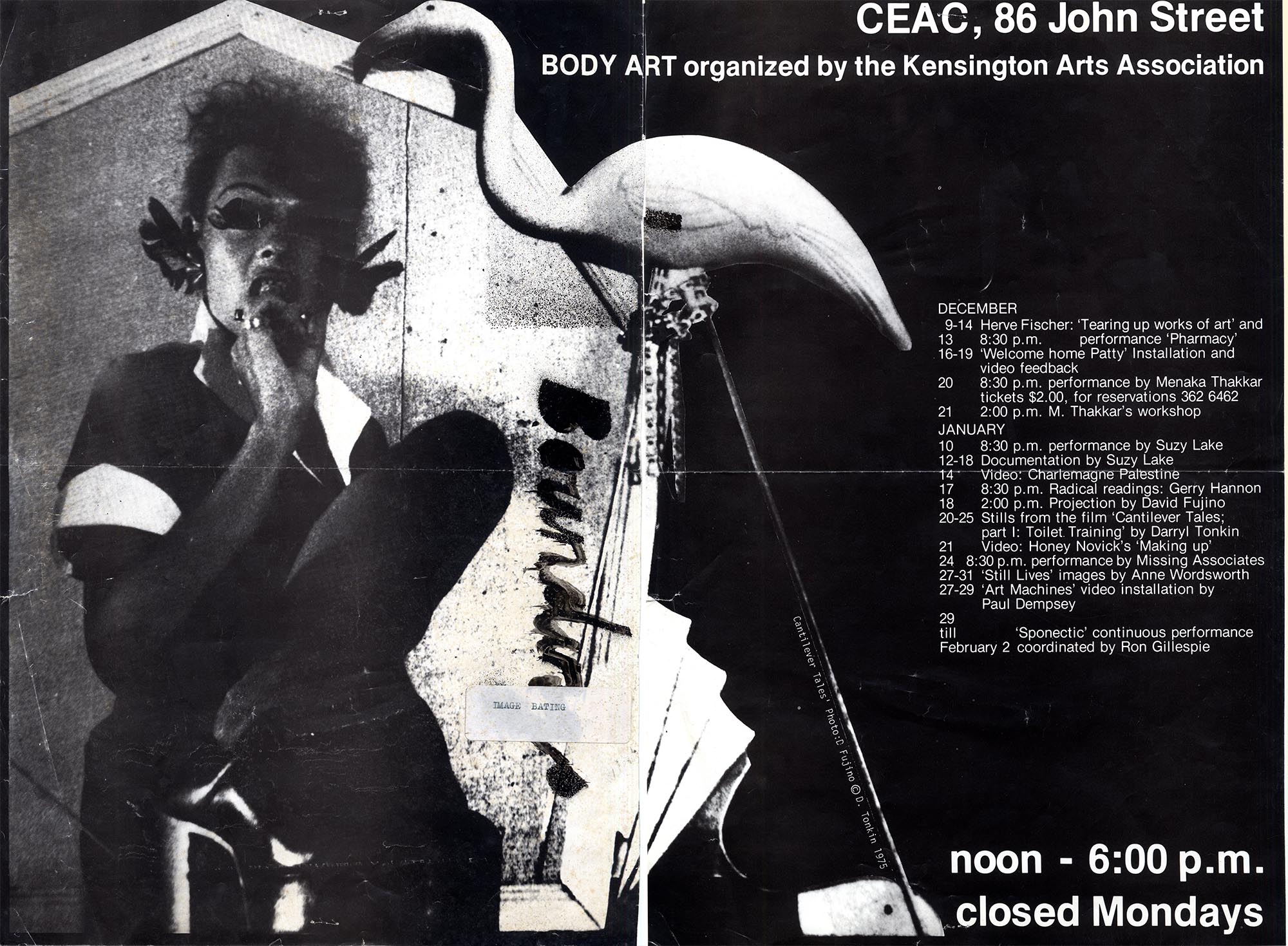

Suber: KAA had served its purpose in training us and we wanted to do something more meaningful. The idea for CEAC (Centre for Experimental Art and Communication) was born. We moved the organization to 86 John Street. Though I don’t remember buying that property and we didn’t stay there very long. We did set it up as CEAC and I have a small scar under my chin as a permanent reminder of the place. The building on John Street was already shaped in a convenient way. We did less renovations there than our other spaces but that did not prevent my trip to the hospital as we boldly swept through the place to remove the artifacts of its previous use.

As I said, Amerigo had a good idea for potential and the sale of the 4 Kensington property proved that. We leveraged a very small investment into a decent pile of cash and headed to the Ontario Arts Council and Wintario. That’s where my skills and experience became an asset: providing a positive and credible representation of a struggling arts organization. Whether it was the Ontario Arts Council or the Canada Council, I translated visions and ideas into budgets and presentations. Wintario matched the gain that we had made on the Kensington property, and we transferred our personal gain into a not-for-profit contribution. There were no fat cat donors so the CEAC board was free to get itself into all sorts of trouble. Of course, the trouble came late in the story.

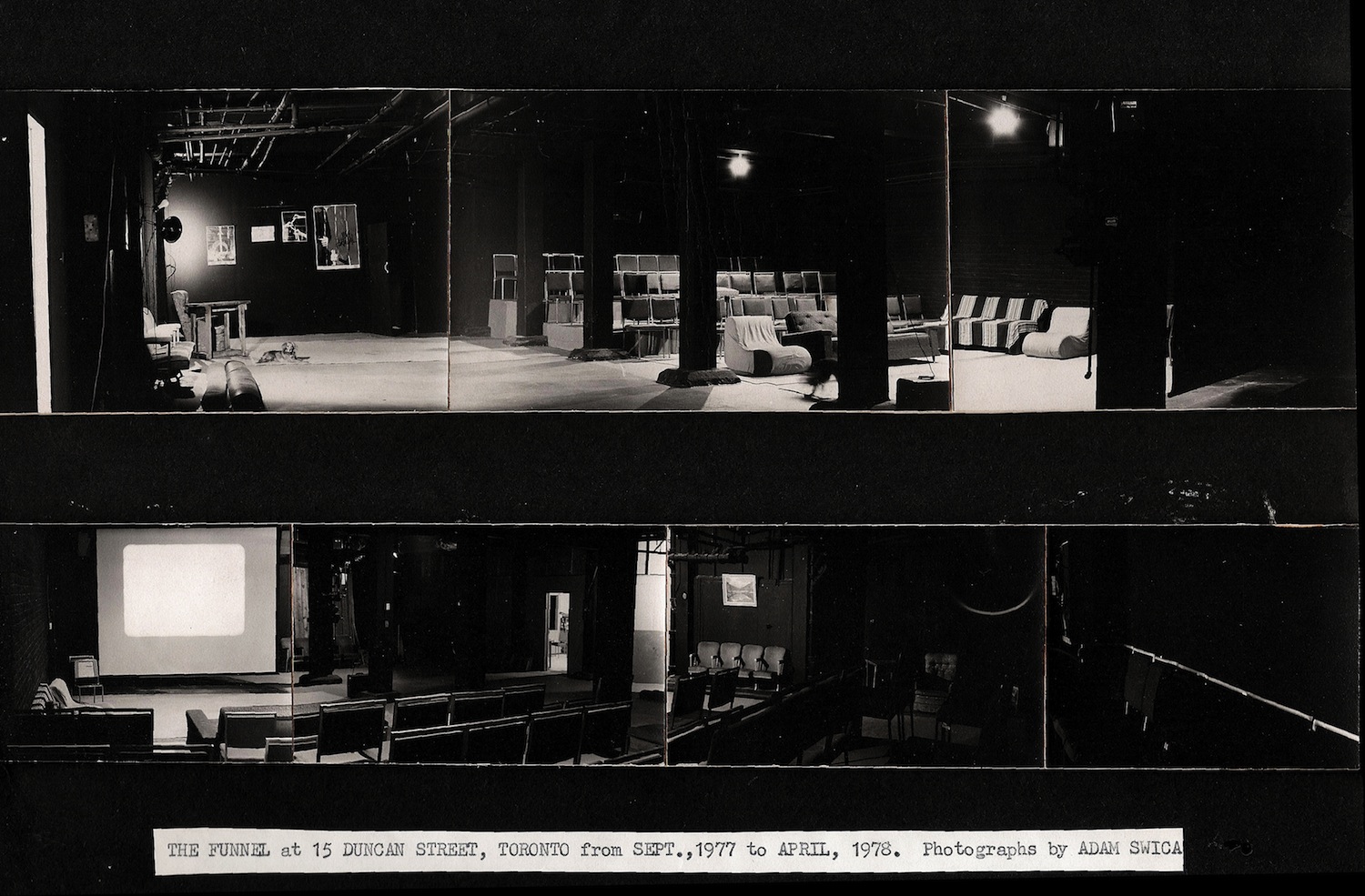

The Duncan Street building, of course, had the best bones, but we removed small rooms that had been built on the top floor to take advantage of the large open space that the warehouse architecture afforded. By the time that we got to Duncan Street and CEAC’s full incarnation, we had a lot more help. Again, these were not paid or professional craftsmen, but artists from the emerging CEAC community who could provide raw muscle power.

Amerigo and I did provide as much funding for CEAC as we could. Making the CEAC possible was our mission. There’s no quicker way to make something happen than pulling out your own checkbook. While I’m sure that few if any were aware, but I developed a great working relationship with our local CIBC branch manager. He was great at providing bridge funding for CEAC when we didn’t have the cash but were expecting some. Given the trouble that we had at the end, he probably would not have wanted to admit it, but he was instrumental in smoothing the way for us.

Mike: How did you get along with the provincial and federal arts councils?

Suber: In those days we had good relationships with officials from both arts councils, arts groups like ours generally did, it wasn’t personal to CEAC. There weren’t a lot of groups that were trying to do really different art in those days, but the bureaucrats who held the keys to the treasury liked being around young, bright, adventurous types rather than the cookie-cutter artists that typically graduated from art school in those days. Or at least, that’s my impression and memory of the situation. I think that this tendency on the part of the arts grantors was one reason why we went as far as we did with public/taxpayer support.

Mike: In an interview in Only Paper Today, Amerigo alludes to a wealthy patron who was secretly underwriting CEAC’s activities. There are still rumours floating around that name this donor as Jane Jacobs. Can you comment?

Suber: You have the answer about Jane Jacobs and a mysterious lady donor. You have to understand that Amerigo would have you on if you were gullible and he thought it would serve his purpose. While you may consider that we were being generous with our own financial support, we were somewhat embarrassed that we could not garner enough support from elsewhere. We knew that the organization would not be sustainable existing solely on government grants and wanted to project that we had a broader audience of support than we had. A mysterious, rich donor puffed up our image.

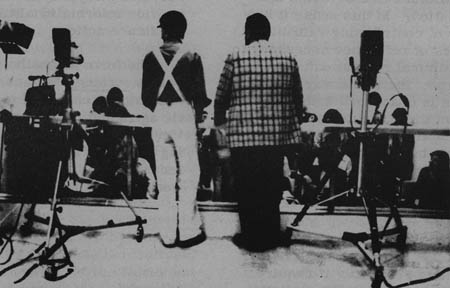

The CEAC European tours (and yes, I was lucky to able to join one of them) were the best things that we did. They brought a sharing of ideas — not just our ideas going to European audiences but exposing Canadian artists to the broader world. While I think that a lot of this was artist-to-artist communication and sharing, it was valuable.

Did the people get what we were doing? Certainly the audiences got what we were doing. However, European audiences at the time were more open (more sophisticated?) than the Canadian ones.

Mike: CEAC housed a super 8 distribution service helmed by Janet Sadel for a brief moment in 1977. Can you shed any light on how that happened?

Suber: Janet Sadel was in the CEAC orbit. The whole Super 8 community was adopted by Amerigo for their freedom to express themselves without being encumbered by a lot of tradition, technology or structure. The same was true, though it was more costly, for the video artists who worked at CEAC. The idea was to build a heterogeneous community of artists and art forms. By the time that we had organized into CEAC, only Amerigo and maybe Bruce, were able to keep their hands in all the activity. In the midst of all of this, I had a straight job which I kept until the troubles came.

One of Amerigo’s techniques was leveraging the attraction and reputations of the old guard for the growth and future of the new generation, juxtaposing the two for mutual benefit.

Maybe it was inevitable that CEAC collapsed, I continue to think that we could have done so much more if we had not found ourselves surrounded by humourless, uncreative, un-thinking reactionaries. The way that Canadian politicians caved in to the mad howling of the right-wing media reminds me of the political environment that exists in the U.S. today. And, of course, you’ve figured out that our “friends” should count themselves in that same category. They all ran for the hills when they smelled trouble. All the hard work and giving was quickly forgotten. However, if our demise had occurred ten years later, I can imagine the story being recorded as a musical for the Broadway stage. So much drama, so little laughter.

Canada and Canadians, at the time, seemed so distant from the events that were taking place in the U.S., Europe, South and Central America, Southeast Asia — in other words almost everywhere except Canada. Mind you, there was turmoil in Quebec but nothing that might prevent a weekend trip to Montreal. The isolation of Canadians undoubtedly fueled the frustration that led to our demise. There was a lot of cute, unconventional art but very little that was provocative. Mr. Peanut never made anyone think, did he?

At the same time, our intellectual forays with visiting artists from the U.S. and Europe were not quite satisfying, either. They were more accepting of us, more likely to want to share and to support in their own way, but, at the end of it all, many were more interested in having careers than creating change. So, yes, I agree that eventually art was no longer “enough”. However, what we were doing was still intellectual and not radical. We wanted people (all people) to be more open to new ideas and less dependent upon the old. We wanted to support those that were ignored by Artforum and give them a forum. At its core, we also wanted to be stimulated by those that had ideas beyond our own. We were selfish in that way. We wanted to grow and to improve and we wanted access to intellectual power. But, we did not want to keep it to ourselves, we wanted to share it. That was the objective. Building. Thinking. Sharing. Supporting.

Mike: Bruce Eves (who worked at CEAC) said that there was a break between artists who had been associated with CEAC for a while (Peter Dudar, Lily Eng, Ron Giii) and a new crew who included Paul McLellan, Roy Pelletier and his pal Bob Reid, and that they changed the direction of CEAC and the increasingly militant tone of Strike Magazine. Here is Bruce in his own words: “It was with the second issue of Strike that the break happened. And with the break came a change in attitude. Peter Dudar said that the place was suddenly remote and closed off, the inner sanctum of the office was off limits and casual drop-ins were discouraged.” Did you feel there were two distinct groups or periods when CEAC was at Duncan Street?

Suber: I believe that what you are describing was more evolutionary in Amerigo’s development than it was anything else. This schism also occured at the KAA. In the very early days, KAA was open to more traditional art forms. Gradually, the shift was made to conceptual/contextual art. That was the art that was brought forward to the CEAC. As more non-artists (or non-practicing artists) came into the environment, the focus on politics surrounding art became more prominent. I would place Roy, Bob and Paul into this category of non-practicing artists. What I’m saying here is not my personal attitude towards individuals but rather my recollection of the process that Amerigo went through. I saw and experienced the transformation. Yes, Dudar and Eng who were at one point the radical element within CEAC became the old guard fairly quickly. Amerigo became more and more interested in the intellectually radical elements of art and was more influenced by those people, particularly from Europe. The New York school (which included much of Toronto’s native talent) was rejected in favor of Berlin, Warsaw, Rome, Florence and Bologna.

Mike: Did you ever attend any of the super 8 open screenings in the CEAC basement that were organized by Janet Sadel, and then Ross McLaren and Adam Swica? Both Ross and Adam said they lived in the basement at different moments, though Bruce (Eves) said it never happened. You and Amerigo were living upstairs, can you shed any light on people living in the CEAC basement?

Suber: Sorry, I’m with Bruce on this. If Ross or Adam lived there, perhaps, it was very temporarily and very close to the end. I did experience the Funnel, I don’t remember it being very well attended. This, too, was a schism. The Funnel was not headed in the direction that Amerigo was. It was too artistic and not intellectual enough. However that schism never prevented Amerigo from wanting to support the Funnel crowd or their work.

Mike: Can you talk about what happened after you left the Duncan Street loft and moved back to the United States?

Suber: The New York experience was meant to follow the inclinations of the late CEAC without the trappings of a major center. We wanted to be smaller, but still a player in the forward movement of art, architecture, intellectual thought, and politics (with a small “p”).

The original intention (as stated in documents that I do not have) was that New York was a subsidiary of CEAC in Toronto. That was the intention but it never really evolved. Bruce and Amerigo opened a bookstore in a rented space on Bleeker Street in the East Village. Amerigo made more contacts with intellectuals/artists and this evolved into his architectural and environmental focus. He and Roy organized one or two events in Corsica during this period. In parallel, we bought two side by side townhouses in the East Village and gutted them. You would be shocked at how much we did with our amateur techniques. We blew off the rear roof of one and replaced it with skylights, knocked down the rear brick wall and replaced the wall with giant shuttered windows. The bookstore moved into one of the houses, but there was never a huge amount of activity there.