Broken English: Jan Świdziński and Toronto’s Contextual Art Symposium, 1976 by Sylwia Serafinowicz

“I BOUGHT AIRTICKET IL BE MONTREAL 29/10/76”

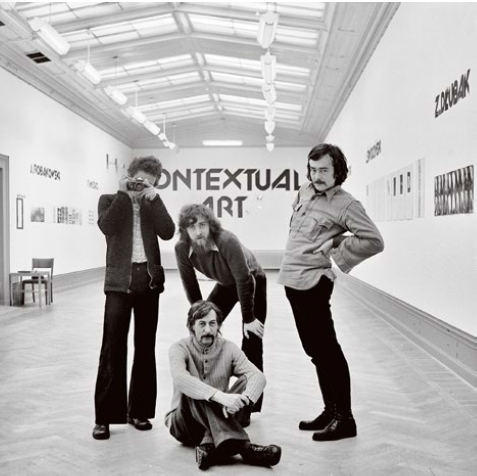

This concise message, a telegraph, was sent by Jan Świdziński, Polish artist and theoretician of Contextual art to Amerigo Marras, architect, curator and one of the founders of the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication (CEAC) in Toronto. It announced Świdziński’s impending arrival for the Contextual Art Symposium, to be held in Toronto in November. At the same time, this modest document reveals part of a broader exchange between two men who collaborated on this event, despite broken English, different customs and the tardiness of postal services. Their letters crossed the ocean back and forth, to bring to life an event that gathered artists, critics and theoreticians who were on the lookout for practices that combined conceptual attitude witih social engagement. The event gathered artists, critics and curators from several countries (including the United States, France and Poland) to explore the role Contextual art would play as a counterpoint to Conceptual art.

The symposium went on to become of the most mythologized events in the history of Polish art of the 1970s. (1) The popularity of Świdziński’s theory at that time is undeniable. It travelled from Poland to St. Petri Gallery in Lund, where it was picked up by Amerigo Marras and later republished by Chantal Pontbriand in Parachute, the Canadian magazine devoted to the merging art of its time that was founded in 1975. (2) However, I argue the reason for this popularity was not the cutting-edge character of the theory as such, but its mobility in terms of language (English) and the adaptability of its meaning. The theses of Contextual art, similarly to the theory behind Conceptual art as it was written by Sol LeWitt and Joseph Kosuth, could have been applied and interpreted in variable contexts. For instance, in “Twelve Points of Contextual Art” (1976) Świdziński argues that every work of art exists in a context and that the context and the work of art mutually and perpetually influence each other. However, Świdziński does not base his analysis on specific artworks nor situations, and as a result he creates more of a universal theoretical framework that can be filled with individual points of reference, rather than a site-specific study. He does not contextualize his theory during the seminar either, on the contrary. He remains significantly less active in speech than the other participants, which might be due to the fact that he did not feel entirely comfortable speaking English. When asked to present a statement, he replied bluntly: “Well, I have described my position with this little yellow book and then I have written the “Twelve Points of Contextual Art.” Because, this text is pictured on the wall, and all the people have this text, I think that would be enough.” (3)

The theoretical framework created by Świdziński, and the space he left open for interpretation, was eagerly filled by the participants and organizers of the seminar. Świdziński’s attempt to connect artistic practice with its social surrounding suited the counter-establishment profile of CEAC. This artist-run institution combined the experience of Conceptual art with practices such as body art that challenged existing social and gender stereotypes. (4) CEAC was established by the Kensington Arts Association, which despite a rather posh-sounding name, was an avant-garde artist collective. It existed for a short time, between 1975 and 1978, and was located first at 86 John Street and, from 1976, in an abandoned warehouse at 15 Duncan Street, where it functioned as a “studio, resource centre, gallery, and performance space for the collective.” In 1977 in the same building, Crash ‘n’ Burn, the first punk club in Canada, also opened.

Hervé Fischer from Collectif d’Art Sociologique make a politically motivated reading of Świdziński’s theory. (5) Fischer introduces himself as a person interested in subverting the existing order, inside and outside the field of art. What is striking about his attitude, however, is that his anger is not directed against one particular political system, but against all forms of existing concepts of power that work to govern the masses; communism and capitalism are here equally detested for their bureaucracy. (6) His comment on the meeting: “My idea would be that I consider this seminar as something very interesting and maybe important, even if the differences bertween us seems very big, because it’s the first time that people working in Europe, East and West Europe, and in North America, come together to discuss the possibility of using art as a way of changing society (…).” (7) Importantly, Fischer’s attitude reflects the state of universal disappointment in the politics that spread across both sides of the Iron Curtain as artists recognized the limitations imposed on arts through censorship, bureaucracy and intolerance under communism and capitalism. Self-organization and collectivity were the tools everyone used to change the rules from within. The English language was the platform upon which these initiatives could meet. (8) Just as Marianne Faithfull sang for the first time in 1979:

It’s just an old war,

Not even a cold war

Don’t say it in Russian

Don’t say it in German

Say it in broken English (9)

Świdziński’s concepts, although criticized by Marras and other participants of the seminar, mostly for being too theoretical and distant from social reality, served as a trigger for further discussions about the ways art after Conceptualism can re-engage with society. As such, Contextual art travelled further and evolved both as a form of artistic practice and in subsequent seminars held in Poland and abroad.

Sylwia Serafinowicz is a Collections Curator at the Wroclaw Contemporary Museum, Poland. She is also a PhD candidate at the Coutauld Institute of Art in London, member of the British section of AICA and a regular contributor to Artforum magazine.

1. Its fame, however, seems proportionate to the scale of material currently left unresearched. Most of the writers who have touched on the subject so far have focused on a close reading of Świdziński’s theory encapsulated in the yellow book titled, Art as Contextual Art, published in 1976 by Jean Sellem, the manager of St. Petri gallery in Lund, and the essay “Twelve Points of Contextual Art” that followed. Information about feedback the theory received in Toronto is scarce. Several publications and films give special focus to the encounter between Jan Świdziński, playing the role of the father of Contextual art and Joseph Kosuth, portrayed as the spokesman of American Conceptual art. The process of glorifying this encounter between two artists and thinkers reached its climax in a documentary film from 2009, realized in a collaboration between Jan Świdziński, Lukasz Guzek, a critic, and Piotr Weyhert, artist and film director, titled Jan Świdziński: In the Context of Art. The crucial part of the film is a depiction of an arranged reunion between Kosuth and Świdziński in 2007 in Kosuth’s studio in Rome. See also L. Guzek, “Context and local actions: Background information to developing the Local Actions Project,” The Recent Art Gallery, A. Markowska, Ed., (Wroclaw: Wroclaw Contemporary Museum, 2014), 325.

2. Świdziński, “Art as Contextual Art,” Parachute 5, Winter 1976.

3.York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections, Centre for Experimental Art and Communication (CEAC) fonds (F285), 1981-010/014(6) Contextual Art, Day 1, Basic Editing, transcript, p. 2.

4. CEAC in December 1975 held an event titled “Body Art” which consisted of a series of performances, projections and readings.

5. Collectif d’Art Sociologique was a collective of artists: Hervé Fischer, Fred Forest and Jean Paultineau established in 1974 in Paris to rethink the relationship between art and society.

6. (…) if we consider the political function of Marxism in our society just now, I think it’s very often not a way of questioning and criticizing only society, but it’s also an answer system, ready-made, to try to get the power, and to get into a bureaucracy. And we have also to ask about Marxism. And materialism does not mean Marxism only, it means just being inside social reality trying to discover the right questions in this society, and not to use idealistic concepts from outside to go farther.” York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections, Centre for Experimental Art and Communication (CEAC) fonds (F285), 1981-010/014(6) Contextual Art, Day 1, Basic Editing, transcript, p. 4

7. York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections, Centre for Experimental Art and Communication (CEAC) fonds (F285), 1981-010/014(6) Contextual Art, Day 1, Basic Editing, transcript, p. 4.

8. Different governments identified a threat in such moves and often reacted aggressively towards them. In the case of CEAC this took the form of an abrupt withdrawal of funding and its subsequent closure in 1978, following an editorial in STRIKE, a journal published by the organization believed to advocate support for Italy’s Red Brigades, the paramilitary group that used organized force to attack capitalism. The final issue of STRIKE proclaimed: “As the futurists were in fascist Italy, as the Bauhaus was in Nazi Germany; as the constructivists were in the Soviety Union, the CEAC was banned in Canada.”

9. Marianne Faithfull, Broken English, 1979.