Missing Associates: an interview with Peter Dudar (January 2015)

Mike: You worked for a decade with dancer Lily Eng. How did you meet?

Peter: I first became aware of her in high school. Even then you couldn’t miss her when she was in the vicinity. In 1969, a mutual friend asked us each to work on a theatre project. That’s when we connected, in the rafters above the stage.

I was painting and included in a show of emerging artists at the Carmen Lamanna Gallery in 1971. My painting was process oriented. Lily was modeling during the day, and taking dance classes at night — some ballet, some modern. But she didn’t fit either mold. Choreographer Elizabeth Swerdlow, after casting her in a shampoo commercial as a dancing nymph, next slotted Lily into a dance theatre production at Global Village Theatre called Transmission. It was an ego boost, but like all existing dance avenues it allowed no free expression.

Lily and I found a studio in the former Bank of Upper Canada building at Adelaide and Jarvis. We were in the original head office. Now it’s a revamped historic site, but when we were there it co-housed artist studios and an egg processing plant.

Mike: Were there a lot of artists living in warehouses at that time?

Peter: The arts community was relatively small and frequently on the move. Every time artists raised the value of a building they got the boot. 2000 square feet was the holy grail, but 1500 was doable. Now, 400 square foot spaces pass as studios. And gallery spaces have likewise trended downwards. Few galleries now could accommodate a piece like Crash Points, which I was able to do live across Canada during the 1970s.

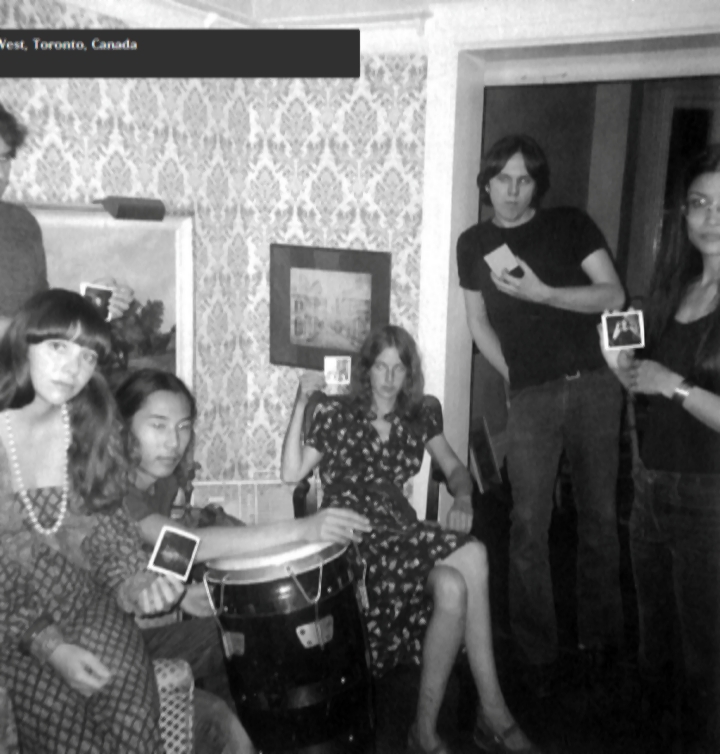

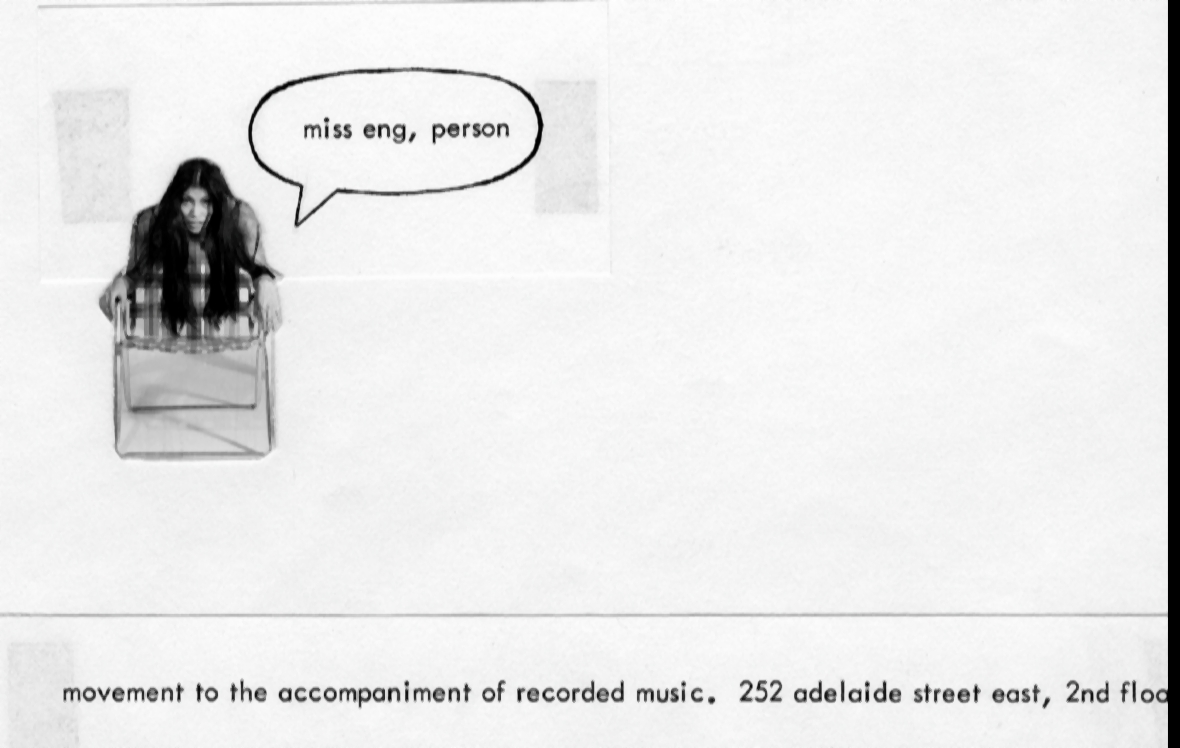

As I said, Lily had no outlet for her creativity. I had transitioned from painting to doing action-related installations. We did our first collaboration in 1972, hosting it at our studio. I made the poster (and all subsequent Missing Associates graphics). Lily improvised, I handled the technical aspects. The performance was called Ms Eng, Person. I subsequently slurred “Ms Eng” to create “Missing” and added “Associates” to it.

In that first studio performance, we used Philip Glass’ Music With Changing Parts (1970), which a friend had brought from New York. On an obscure label, it was probably one of this first recordings to show up in Toronto. I blasted the music into the studio while Lily at some point stripped very, very slowly. It wasn’t yet the worst cliché in performance art. John Martin, who later conceived MuchMusic and The New Music, was in that first audience. He didn’t get the art part but thought Lily looked fabulous. And he later telecine’d most of my films at CityTV’s facilities.

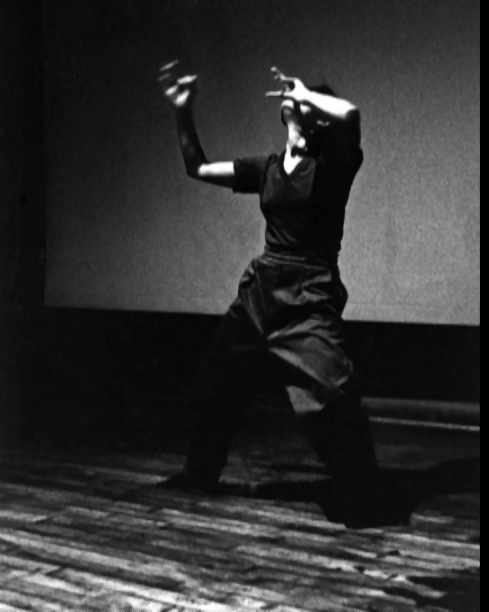

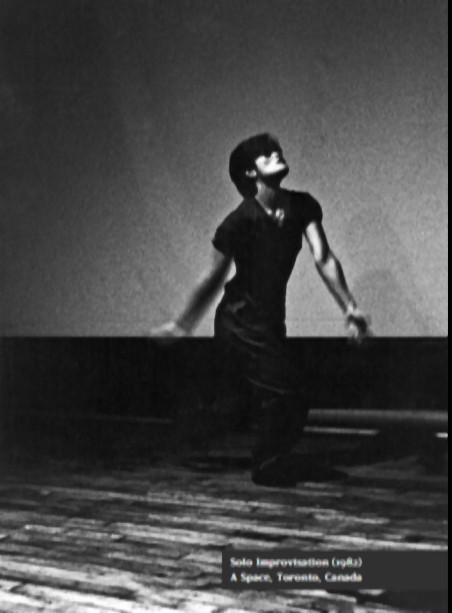

The intent of our first performances was to invent a vocabulary, start from zero. I included a quote on one of our posters that the discovery of zero was the greatest achievement in science. Body movement was severely restricted. We did a number of pieces where we pumped propulsive music (such as the Stooges Down on the Street) into the space or into individuals’ headphones and told the performers not to react to it, not to move, not to dance. We wanted to observe involuntary movement and worked with non-professionals. We saw what worked and what didn’t, and then created structures we could play within. Eventually I hybridized performance concepts and film. Lily developed a deeply personal vocabulary. You had to be Lily to do a Lily Eng piece.

Mike: How did you transition from performing in your own space to working in the galleries?

Peter: After showing at Carmen Lamanna Gallery, I had done an installation at A Space, a relatively new parallel gallery at 85 St. Nicholas Street, near Yonge and Bloor. So they knew me.

Mike: Was it hard to get shows at A Space?

Peter: I would walk in and tell the director onsite that we wanted to do a performance in a few weeks. He or she would confirm on the spot, and then we would go ahead and do it. There was no submitting a proposal to a collective and setting up something for a year and a half later. Coman Poon, who curated our Missing Associates eBook launch, bettered this recently, setting up the launch at Cinecycle by phone in just a few minutes.

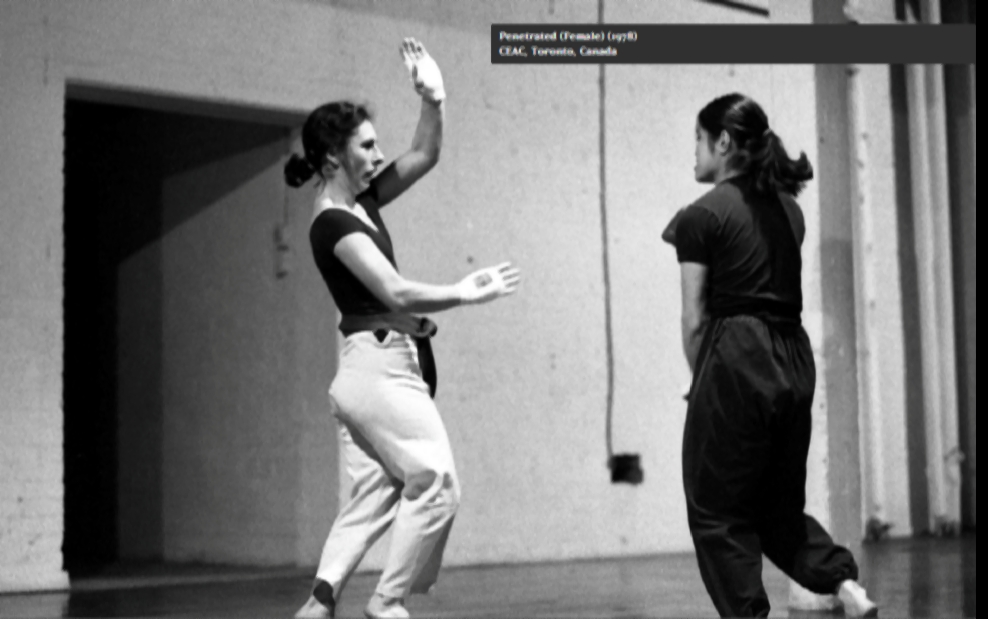

We did thirteen performances at A Space. The first was in 1973, before the Toronto experimental dance scene had come into being. We subsequently did a dozen at 15 Dance Lab.

We saw lots of New York underground film. At one point we were living in the same building as Philip Glass, at 10 Bleeker Street, and could hear him rehearsing. We picked up the first imports of The Sex Pistols and The Clash and listened incessantly to Miles Davis. We were huge fans of Yvonne Rainer — we saw her do This is the story of a woman who… (1973) in a small theatre on the lower east side. The Michael Snow films that most affected me were Back and Forth (1969) and especially La Region Centrale (1971). I saw La Region at Anthology Film Archives on Lafayette Street. There were barriers between every seat — presumably to minimize distractions, but it seemed porn-like. I don’t know if it was Snow’s doing. By the time I screened Running In O and R (1975) at Anthology’s Wooster Street location the seating was conventional.

In Toronto, Lily and I were seeing at least one movie per day. Our tastes ranged from Warhol to Bresson. And Godard, of course. The Cinema Lumieres came and went, but we probably saw more films at the Roxy than anywhere else. It was a rundown theatre on the Danforth, an early venture by The Gary’s. 99 cents per screening. They kept a slew of pennies at the door since nearly everyone paid with dollar bills.

Mike: Mike Snow often works with rules or restrictions. Did you pick up that aspect of his making?

Peter: Rules and restrictions are how you manage non-professional performers. The rules and restrictions in our early works were not related to film, they were about controlling live situations. It’s pretty hard to see film connections in Lily’s improvisational solo work. She’s all about being live and in the moment. What I saw in structural film was the possibility of developing rules that meshed both live behaviour and camera behaviour. In my mixed media pieces and standalone films the performers and cameras were choreographed congruently.

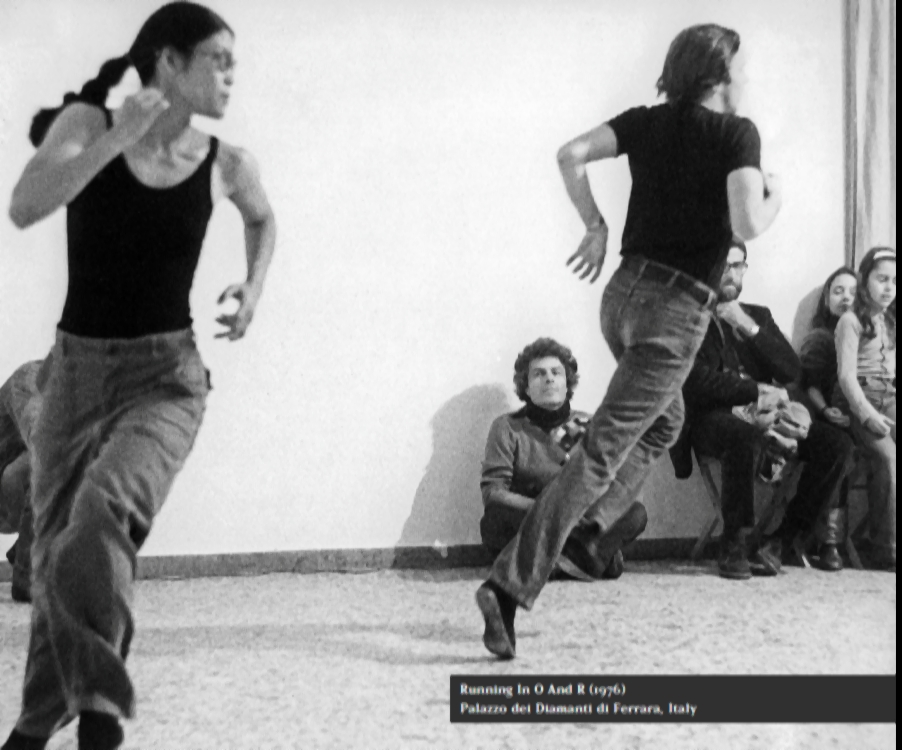

By the mid-1970s I was working with people who were reasonably athletic, though not dancers. When I put performances on film, I was not making orthodox structural films. In a structural film a set of rules is imposed by the filmmaker that obtain from beginning to end. Someone can walk into frame, shoot somebody and walk out of frame but the film continues as originally intended. In my case, the camera always followed the rules, but the performers could do things at will to alter its outcome. Some of the structure was coming from inside the film, from the performers. In Ferrara Italy, I remember an intense debate amongst the audience about whether Crash Points (1976) was socialist, which seemed absurd at the time, but maybe there is an argument to be made that Crash Points is socialist.

My first 16mm film Walking Away (1974) was very simple. Lily, on a plateau above the Scarborough Bluffs, walked away from the camera toward a treeline on the horizon. At the treeline she turned and crossed the frame, but instead of panning with her the camera zoomed out to keep Lily in frame as it revealed the entire landscape. It’s a very simple thing. Recently I shot some HD footage in Toronto’s Port Lands that had some comparable movement in it; so I matched it with what Lily had done in the earlier film and re-released an expanded version called Walking Away 2 (1974-2011).

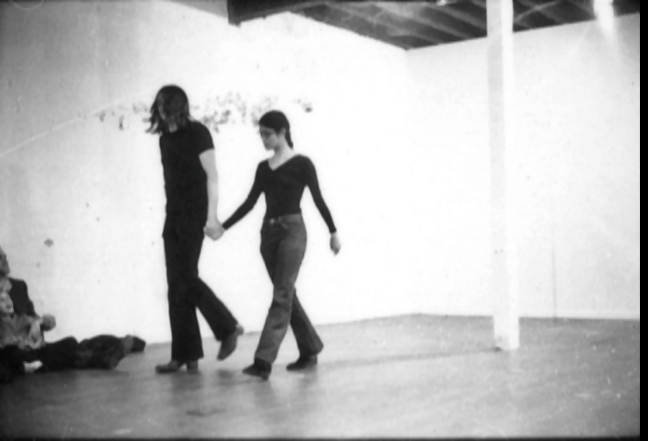

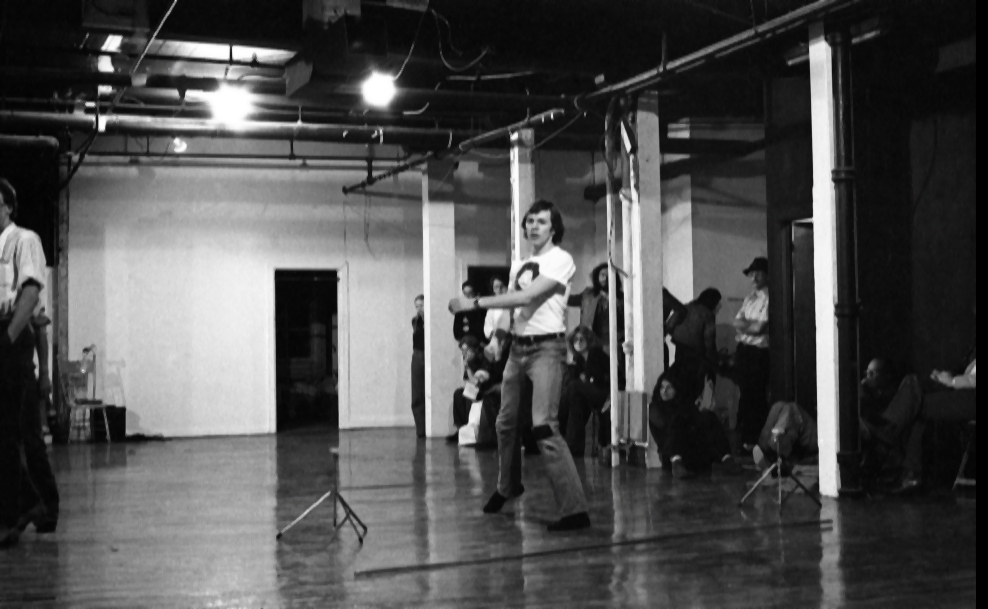

There were three of us involved in making Running in O and R (1975). Lily and I were the main performers, Keith Lock handled sound and camera. We were running around the circumference of the space, basically running in step, but we circled the room at different rates because of our differing strides. At the beginning the camera is immobile and set wide, you’re seeing the whole room. Then the camera cuts closer and follows one person, then the other, panning continuously. There’s a point where Keith, the cameraman, lets the camera run and gets into the mix. It was shot at 86 John Street, the original CEAC (Centre for Experimental Arts and Communication) location. Recently, the building was used as the construction office for TIFF (the Toronto International Film Festival theatres) and is the only non-high-rise left in the area.

CEAC started off as the Kensington Arts Association (KAA) in a row house in Kensington Market. Amerigo Marras and Suber Corley were running a gallery in the gutted first floor. I participated in a visual arts show there, but don’t have vivid memories of it. Not too long after we connected with Amerigo and Suber they moved KAA to John Street and renamed the organization. The John Street building was a raw two storey warehouse. We first performed there in 1976, in CEAC’s Body Art series.

Mike: How did you happen to enter the Kensington Arts Association?

Peter: As I’ve mentioned, Lily and I had been working as Missing Associates since 1972, performing mostly at A Space and 15 Dance Lab where Amerigo had seen us. When sifting through Missing Associates’ photo archives more recently, I started noting faces in the audience. At some point, Amerigo starts showing up in the audiences. I think the first time he approached us was at 15 Dance Lab.

Mike: What was Amerigo like?

Peter: Slight build. Pronounced European accent. Erudite. Initially just some guy in the audience who liked what we were doing. We soon realized that he was much more than that. I doubted that he could do what he intended, but shortly after we met, Amerigo and Suber had secured the space on John Street and the programming became interesting. Some original KAA artists fell by the wayside: one became so abusive to me that I threatened to do him in. He was never again seen at CEAC. Just nine months after the move to John Street, CEAC acquired a larger warehouse on Duncan Street. It was marvelous. CEAC had transitioned from a row house in Kensington Market to the largest non-museum gallery in Toronto.

When Diane Boadway and I entered KAA for the first time, Amerigo graciously offered us tea. While he was out of the room, Diane insisted on slipping away immediately. But within weeks, Diane was on staff at Kensington and the two could often be seen strolling down the street arm in arm.

Soon after KAA’s move to John Street, Diane Boadway and I scouted musicians for CEAC. We brought Amerigo a demo cassette from Talking Heads and urged him to book them. He declined and some time later they debuted in Toronto at OCA (Ontario College of Art), packing the house. Amerigo also took a pass on Laurie Anderson. To his credit, Amerigo went instead with Steve Reich and Philip Glass, less commercial choices at the time, but more appropriate to CEAC.

Mike: Suber Corley was Amerigo’s partner. Was he part of your conversations?

Peter: A lot of CEAC’s success was a product of their partnership, the two of them together made it all work. Amerigo was the visionary and Suber was the technician. Suber was fluent with computers, when few were, and worked as a programmer at a bank, later at Citibank in New York. Suber could be blunt, cynical, but he was not up front and vocal; he didn’t talk about art to me. But he was crucial.

Mike: Who was the audience at KAA, or CEAC?

Peter: Besides the KAA/CEAC audience, our performances at John Street drew those who knew us from A Space or 15 Dance Lab. We were part of the experimental dance world as well as the performance art world. A Space’s core group was affiliated with General Idea, who were campy, obsessed with becoming famous, whereas CEAC was hardcore, more punk. But Missing Associates performed at both spaces on an ongoing basis, even after we’d started at CEAC, which no one else did. We weren’t connected with A Space’s core group. They had come out of the Ontario College of Art together, and let us use the space, but nothing beyond that. Amerigo was genuinely interested in what we were doing. Lily and I would frequently converse over dinner with Amerigo, Suber, and whoever was in the office that day, often at Kam Kuk Yuen’s (then on Spadina). If you look at the histories of A Space propagated to date, even though we did more performances at A Space than any other artists, we’re never mentioned. Not once. But it was useful to have us on their arts council applications.

Prior to 1974, the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council had refused to support performance artists. Applications were tossed from one department to another, with none accepting responsibility. After directly confronting Ontario Arts Council officers on the issue, Lily and I were awarded the Ontario Arts Council’s first Technical Assistance Awards as experimental choreographers. Likewise, we directly confronted Canada Council officers in Ottawa. Missing Associates were made the Canada Council’s test case and awarded the first art grants as performance artists in 1976.

We did just three performances at CEAC’s Toronto location and were immediately labeled CEAC artists.

The whole visual arts art scene (not just A Space) was dominated by former Ontario College of Art students. When 15 Dance Lab re-opened as a parallel gallery in 1974, progressive dancers were emerging from York University, and many did their first performances at 15. Lily and I had come out of nowhere. No one knew us. But besides CEAC, at 15 Dance Lab we received a lot of support from Lawrence Adams, who co-directed the Lab.

A Space and 15 Dance Lab sometimes brought in artists from other parts of Canada and the USA, but they didn’t send artists abroad. CEAC, on the other hand, was internationally oriented, engaging with the USA and South America, but mostly with Europe. Missing Associates was on the first Canadian Performance Art Tour of Europe with CEAC in 1976. Lily and I did an early version of my piece Crash Points, which had developed from Running in O and R (1975). It still involved a lot of running around the circumference of a room but now I had added hurdles made out of metal tubing that made a lot of noise (crash points) when they were knocked down.

Mike: The performance is a way of mapping the space, and examines behavior.

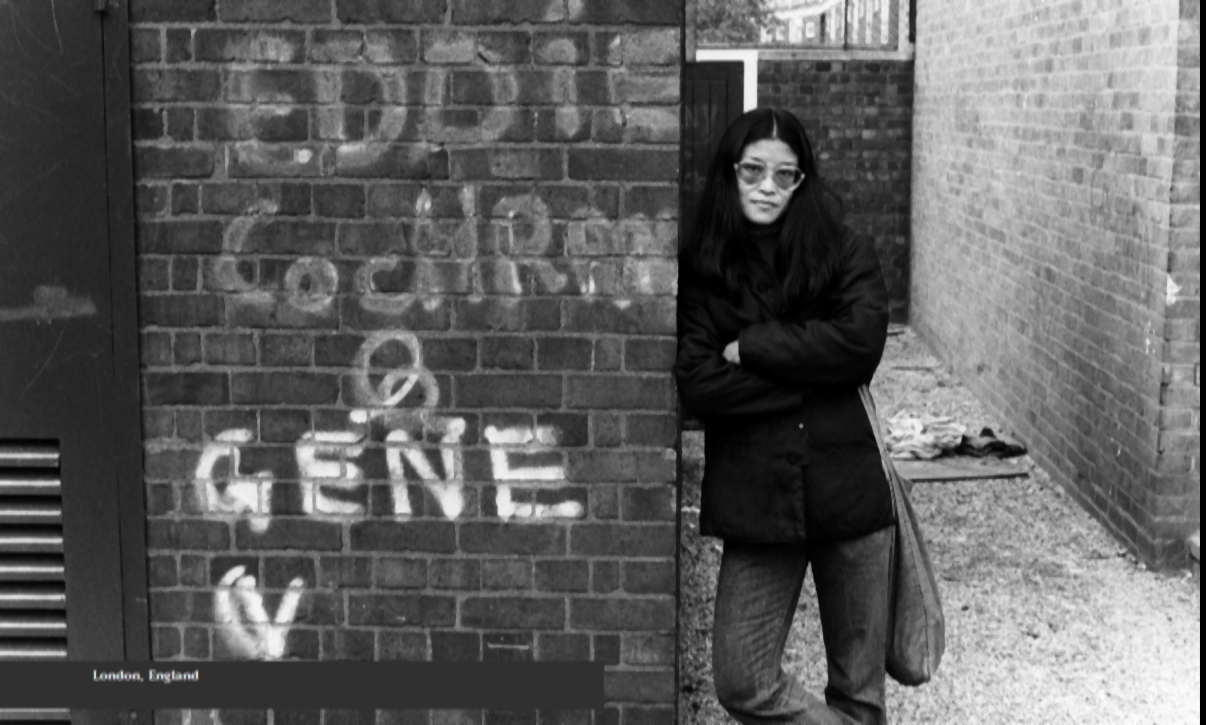

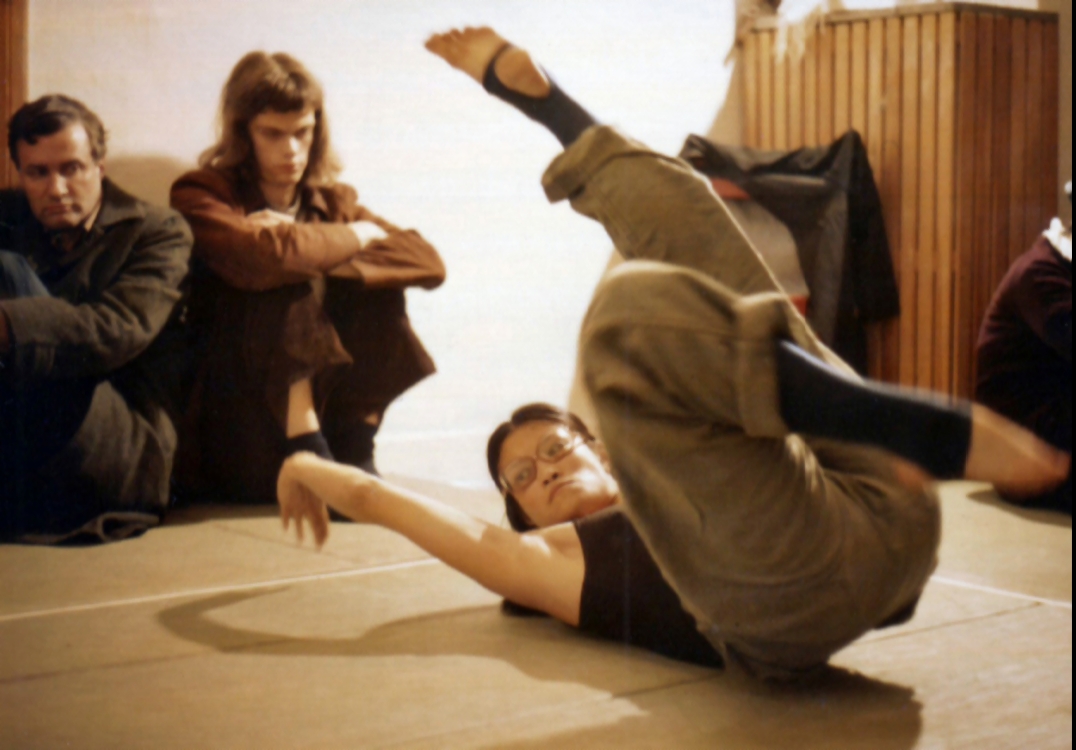

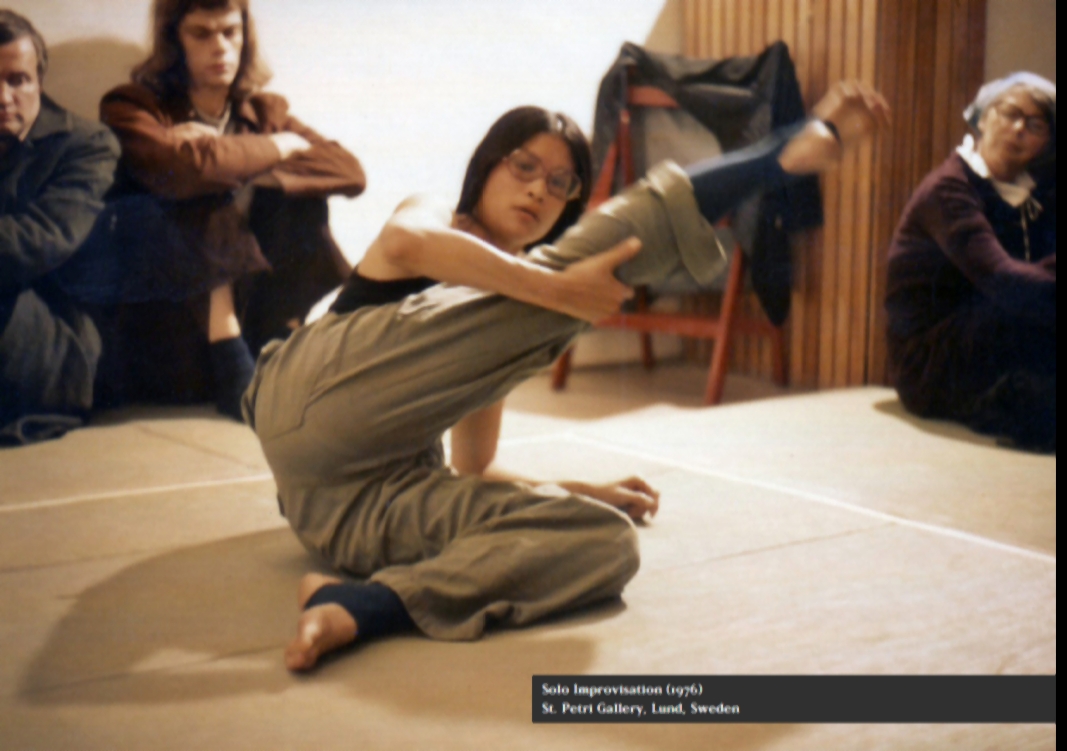

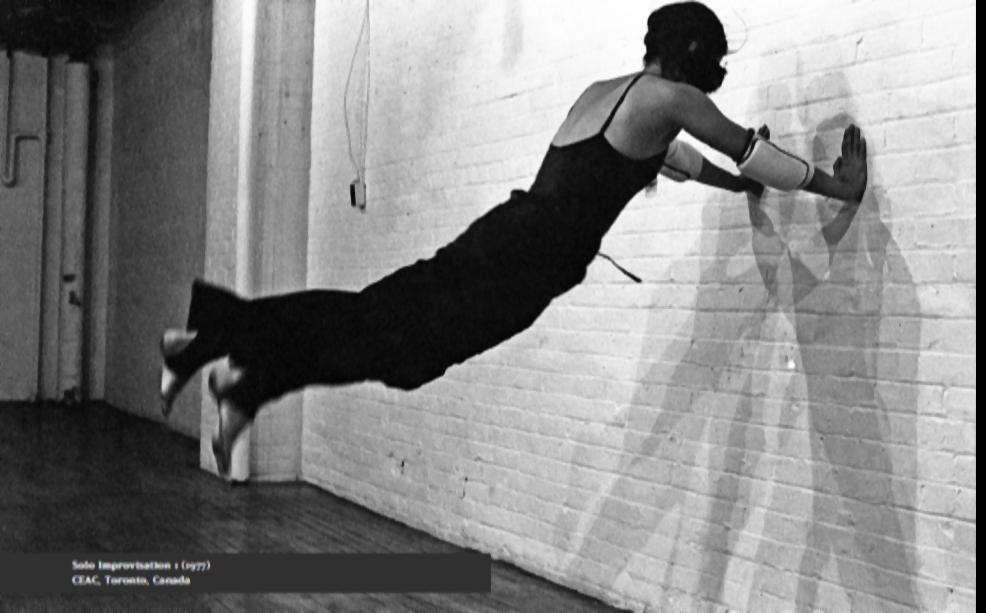

Peter: Yes, within the set of rules, performers could exercise preferences. For example, the hurdles were knocked down at their discretion. In her solos, Lily was doing acrobatic stuff mid-space, but also plastering herself on floors and walls. Because my work required significant space and several performers, I showed my pieces on film in the smaller venues. At 2B Butler’s Wharf, one of our London venues (which has since been condo-ized), I conscripted London artists to perform in Crash Points. The Sex Pistols had also performed there — we would have made a great double bill.

Mike: Some of your performances involved direct engagement with the audiences.

Peter: We did a series of early pieces where we circled the perimeter of the space and talked to audience members individually. Sometimes we wore microphones so everyone could overhear the conversations. We almost always improvised. The basic rule was: don’t stop talking. The only time we actually used a script was in the follow up to I Already said That (1974), which had been recorded and transcribed. In 3 Parts, No Title (1974), we repeated I Already said That word for word. It was sort of a non-improvised improvisation.

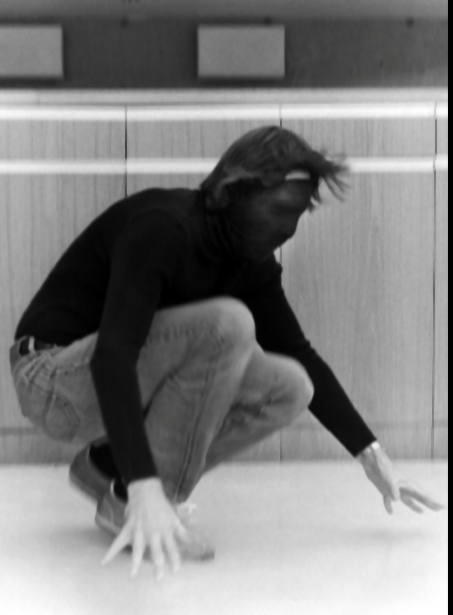

When Lily did her solos she had a way of reaching way, way down into her id. No matter how scary, she’d go with it, spewing it out in movement and vocalizations. Recently I ran into someone who said that he always sat in the back of the room when Lily was performing, afraid that she would hurt him. In one of my photos from Zagreb, Lily is mid-audience, with some guy clasping his face in horror.

Mike: Language featured prominently in some of your work.

Peter: In one very early piece, Vocal Points (1973), Lily and I simply ran through the pronouns: I, you, he/she, we, you, they. The rule was that every sentence had to first start with the pronoun “I.” Then one of us would switch to “you.” After that every sentence had to start with “you.” And so on. It was like a primary school grammar lesson. The piece revved up to a pretend fight. A psychiatrist in the audience, who missed the grammar part, offered to counsel us because our relationship seemed very troubled. (laughs)

Mike: Did anyone ever try to intervene?

Peter: Sure, but not too often. At 15 Dance Lab, a very drunk acquaintance kept coming on to me during a performance, wouldn’t respond to reason. So I flung her over my shoulder, and before she could react, had her out the door. Then I resumed performing as if it had all been staged.

I should mention that Lily held her own both in and outside the gallery. While touring, we were confronted on a highway in Prince Edward Island by three assholes in a pickup truck. I did the guy thing and told Lily to get behind me. Instead, Lily dove into a ditch, emerged with a broken beer bottle, and goaded them to take us on. They slinked back into their truck and drove off.

The most infamous confrontation was at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Looking At Dance – Live, On Film, As Video (1977) was the first time that experimental dance had been recognized by the gallery. We were performing in Walker Court. This was well before (architect) Frank Gehry ruined it. Lily had started one of her solo pieces, was already into the reptilian part of her brain, when a security guard decided to throw her out. He literally grabbed her and started pulling. He had no clue she was part of the program. She threw him off, intimidated him physically, and followed up with a string of expletives. He slinked away.

Mike: Did your work try to blur the lines between audience and performer?

Peter: We used to do that all the time, but less so as the work evolved.

Mike: Did you ever see a show at CEAC that struck you, that made a difference to you in some way? What was it?

Peter: The worst performance was by Willoughby Sharp. He published an influential magazine out of New York called Avalanche. I think that Amerigo inflicted him on us to make the connection. It’s done all the time. But CEAC was supposed to be above that.

At the Duncan Street opening, Michael Snow’s performance was followed up by Ron Gillespie’s (aka Ron Giii). Apparently Ron and his performers threw raw hamburger at the audience. I’ve always felt affected, though I didn’t see it — Lily and I were out of town at the time.

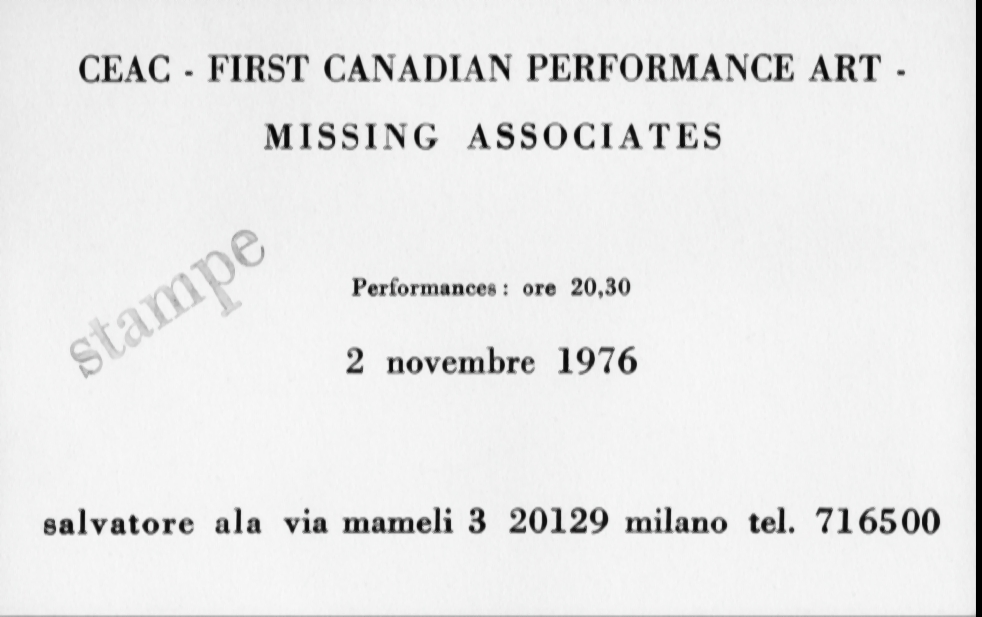

I was thrilled that Amerigo double-billed us with Paul Sharits in 1976. After all, he was a structuralist filmmaker who had figured out how to make watchable super-8 films — I couldn’t. He had convinced galleries to show film as art, as installations. But Sharits didn’t do a performance — just screened footage I’d already seen.

Mike: Can you describe what happened on the CEAC tour? Did all the performances happen on a single evening?

Peter: On the 1976 CEAC tour Ron Gillespie, John Faichney and Missing Associates performed. Heather MacDonald, an installation artist, came along as our photographer. We showed in St. Petri Gallery, Lund, Sweden; 2B Butlers’ Wharf, London, England (Missing Associates); London Filmmakers Co-op, London, England (Peter Dudar); Richard Demarco Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland (Lily Eng); Internationaler Kunstmarkt, Dusseldorf, Germany; Internationaal Cultureel Centrum, Antwerp, Belgium; Museum of Modern Art, Palazzo dei Diamanti, Ferrara, Italy; Cavallino Gallery, Venice, Italy; Salvatore Ala Gallery, Milan, Italy.

Besides the group showings, some of us did individual dates. Lily did a performance in Scotland. I did a screening in London. When we all reconnected in Antwerp, Ron was in bad shape, having subsisted for some time on Belgian chocolate.

Amerigo was MC and translator. In Italy especially, performances were usually followed by intense discussions. At The Diamond Palace in Ferrara, Amerigo got into a heated exchange with an audience member, someone he knew, who was dismissing us as capitalists. How could she wear designer clothing exclusively, drive a Ferrari, and live in a mansion with servants, yet still be a Marxist, he challenged. “I’m going to give it all up when the revolution comes,” she responded.

During Missing Associates’ Cavallino Gallery performance, much of Venice was under water. Even the gallery floor was a shallow lake. The audience were in formal wear and rubber boots. It felt like we were reliving an Yves Klein Anthropométries performance, circa 1960. In the circumstances, I reluctantly reprised a walking-based piece, Prime And Retrograde Walks (1975) which Lily had also previously done. Mid-performance I yelled at her to run. Though otherwise following the rules, we slipped, slid into walls, and sprayed water everywhere. Then the gallery’s movie projector literally went up in flames.

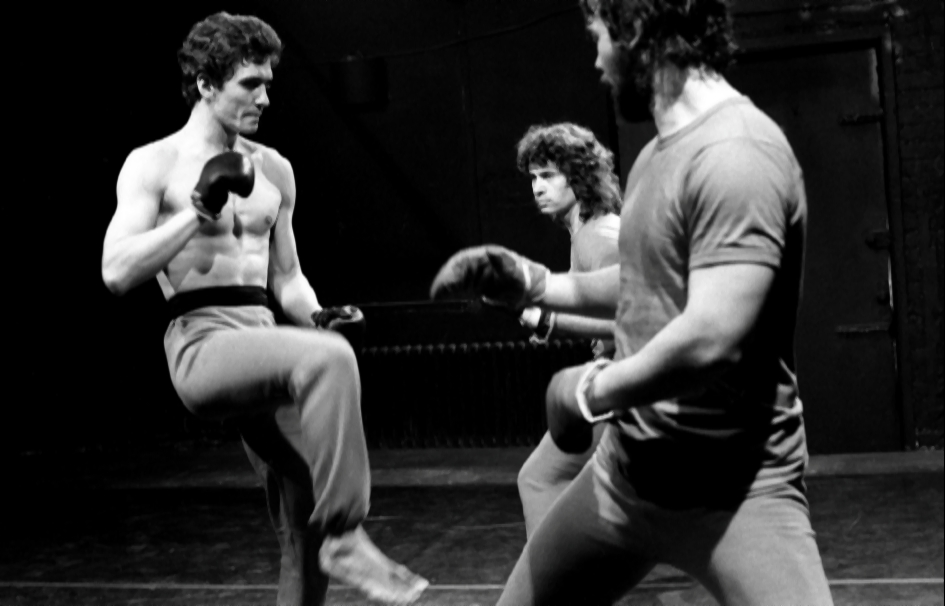

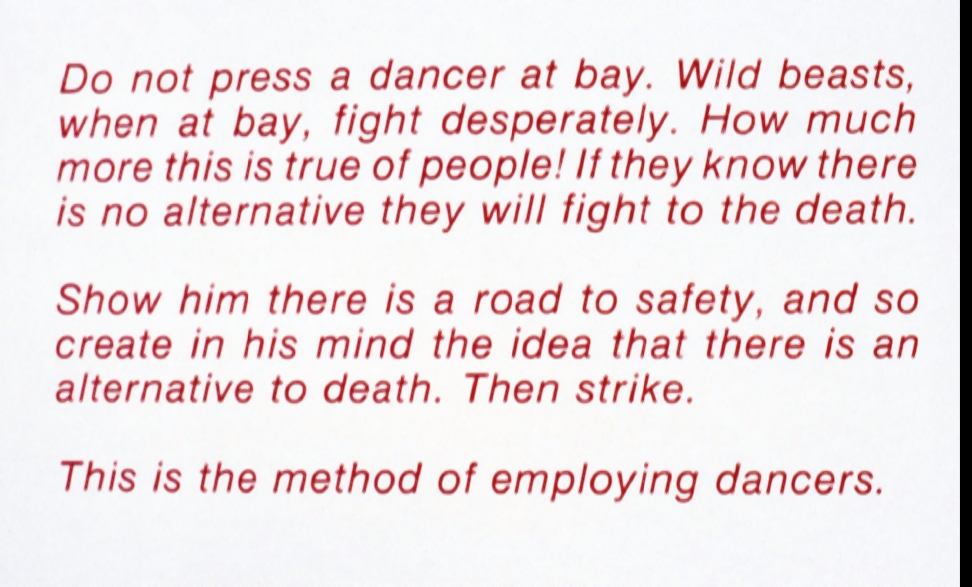

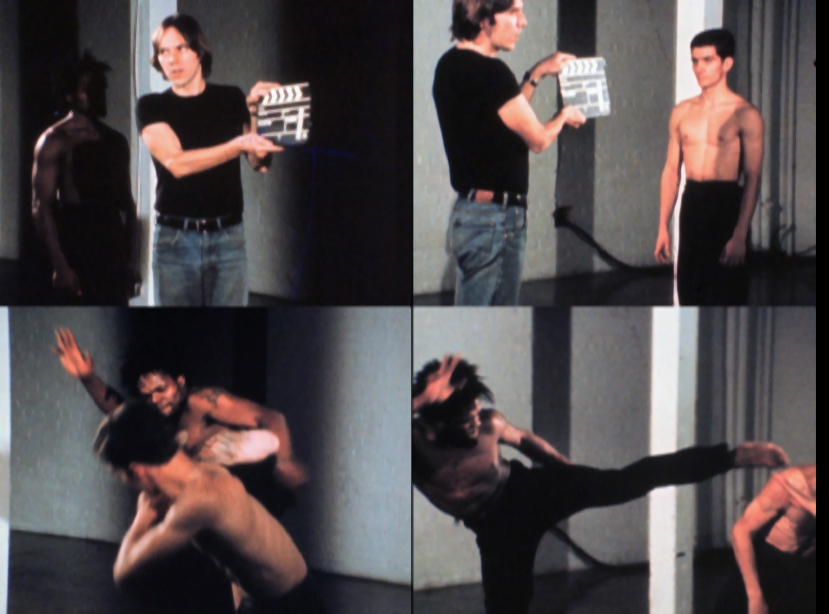

Mike: Could you talk about The Dogs of Dance (1979)?

Peter: The Dogs of Dance was done with martial artists. I filmed a number of sparring sessions: one on one, then two artists unfairly ganging up on one. It was all intercut with quotes from vintage and contemporary martial arts texts, like Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. The running joke was that I slightly misquoted the texts, substituting the word “warrior” with “dancer”, or the word “war” with “dance”. I was positing the notion that martial artists were dancers, but much more useful. “Don’t back the dancer into a corner, allowing irrational and non-rational forces to come into play.” “All dance is based on deception.” Dancers didn’t think it was funny.

Mike: Did Missing Associates make political art?

Peter: Not really. We brought the audience into the performance, and vice versa. On that level you might construe it as political. Sometimes I’d put political-sounding titles on pieces, but tongue-in-cheek. The political texts in The Dogs of Dance were Dadaistic humor. The last thing I did under the umbrella of Missing Associates was an early version of what became the film DP (1982). That was deadly serious. It was based on the autobiography of a Ukrainian who escaped Hitler’s and Stalin’s genocides.

After the 1976 CEAC tour, Lily and I set up a tour in Western and Eastern Europe in 1978, and then followed up in 1980. We sourced some of the 1978 venues through CEAC, but these were Missing Associates tours. Lily performed at Joseph Beuys Free International University at Documenta 6 in Kassel (1977), as part of CEAC’s Violence and Behaviour Workshop. That was the last time either of us performed with CEAC. From 1976 to 1980 we were also doing one-offs in Europe between tours, all self-produced.

People think I’m joking when I say that the beginning of the CEAC’s downfall was when Amerigo decided he was an artist, not just a curator. The responsibility of a curator is to see what’s out there, find patterns, and bring it to people’s attention. When a curator decides he’s an artist, puts himself into performances, everything becomes oriented towards that person and what they’re doing. As a curator/artist, he has the resources of the entire organization at his disposal and its nearly impossible to resist dictating the direction that the art scene is supposed to go. Objectivity went out the window when everything became centered on Amerigo the artist. Amerigo was certainly talented. But unlike Lily for instance, he had no innate artistic talent, so he gravitated to things that got a rise out of people.

Mike: Many of Amerigo’s writings are very Marxist. Did he speak this Marxist language, or was it only part of his writing self?

Peter: Lily and I were not Marxists. And Amerigo never tried to inflict Marx on us in conversation.

I read somewhere that Artforum Magazine became incoherent in the wrong way when it took on a European editor. Couldn’t have been worse than Amerigo’s writing. I rarely read his articles all the way through. Maybe I should have forced myself, in light of the consequences.

Mike: CEAC increasingly turned towards questions of political liberation and the class struggle. Your work sometimes had an aggressive, combative style, with its use of martial artists, for instance. Do you feel there was a connection between CEAC’s urgent militancy and Missing Associates’ confrontational stylings?

Peter: Some. Lily and I were from working class families, so we had lived the so-called struggle firsthand. We didn’t just visit WorkingClassLand, take pictures of the natives, and then sell them in galleries. Our use of martial arts, in part, paralleled experimental dancers going into ‘gentle’ martial arts like Tai Chi — we went into unadulterated street fighting. Kung Fu was seemingly in Lily’s DNA. And one of my former students, Henry Kronowetter, was a spectacular martial artist, poetry in motion, reminiscent of Bruce Lee. He’s in three of my films.

Mike: Art Communication Edition (magazine) was renamed Strike, and new folks like Roy Pelletier, Paul McLellan and Bob Reid were brought into the fold. Is that when the shift happened?

Peter: Yes. Amerigo started to gather people around him who were more interested in political posturing than art. There were people listed on the masthead of Strike, like McLellan and Reid, and I had no clue who they were. Roy at least stayed around in the aftermath. I don’t even know what the other two looked like, just that they ran away.

I’m guessing that the Strike collective were in a bubble riffing off each other, maybe genuinely unaware that they were jeopardizing the entirety of CEAC. At one point Amerigo mysteriously announced to Diane (I think it was) that he was was doing something “really big.” What he was really doing was committing suicide. And I couldn’t figure out whether it was deliberate, a fuck-it-all gesture. Or something else. Editorial and artistic activity at CEAC constantly tested limits, including biting the hands that feed you: the arts councils (Canada Council, Ontario Arts Council). I recall a book about Japanese attitudes to suicide called The Nobility of Failure. Maybe there was some of that in Amerigo…

Mike: Did the arts councils ever express concern about what was happening at CEAC?

Peter: I wouldn’t have known.

After the media leak (May 1978) I could still walk in the front door but Amerigo wasn’t comfortable with me entering the offices anymore. The last time I was there, he had installed a ceiling-to-floor length map of the world centred on Beirut, next to the office door. I have to admit, it was kind of neat.

Anyway, I thought that maybe I was missing something: Amerigo and his cohorts must have developed other sources of income. But it seems they genuinely believed that that the arts councils would not violate their contracts with CEAC. That Strike Magazine would be understood to be a separate entity. The Strike collective, and they alone, deserved what they got for not dissociating from CEAC beforehand, for being too stupid to have a backup plan.

After the scandal broke, Amerigo got a job as a translator for Toronto’s Italian Embassy. They were pleased with him, I’m told, but he was fired when word got to someone there.

Mike: Were you surprised there wasn’t more support in the arts community for CEAC?

Peter: Dadaist types don’t ingratiate themselves. And the Toronto parallel gallery scene was riddled with rivalries. There was intense jealousy because CEAC had managed to develop an international profile, especially in Europe. Amerigo swore that a gallery director had phoned him, crudely demanding that he reveal to her the secret of how he’d managed to crack Europe. I believe it. Missing Associates was once slammed in a supposed review by someone who wasn’t even at the performance. And since Missing Associates performed at 15 Dance Lab, we also had to contend with prissy dance writers. Toronto Dance Theatre wouldn’t even let us post flyers on their bulletin board.

When CEAC went down, there was a scramble by some artists with no discernible connection to CEAC, to publicly dissociate from CEAC. The dread overall was that the scandal would make the two levels of government clamp down on the arts councils, jeopardizing everyone’s funding.

Mike: How was the competition between organizations expressed?

Peter: Spaces had their own social networks and sanctioned art styles. Lawrence Adams of 15 Dance Lab was the exception. I’m told that his attitude when sitting on arts council juries was to award all applicants and let the cream rise to the top naturally.

Amerigo sometimes pretended that CEAC was a collective, but that was fiction. There was the short-lived Strike collective and we know how that turned out. Amerigo totally ran CEAC. Everything was processed through him. CEAC was fast and productive, then Amerigo flamed out.

The artist video production and post-production facility happened, but didn’t reach full potential. Arts publishing and video distribution didn’t seriously get off the ground. The beginnings of CEAC’s reference library got scattered after the shutdown. CEAC started Crash ‘n’ Burn (then shut them down, supposedly for being poseurs). The Funnel (experimental film collective) didn’t come into its own until after CEAC.

CEAC had leased a commercial Xerox copier that was supposed to bring in income. Amerigo used it to publish a bound issue of Missing Associates’ documentation. The original pages were scattered in the interim, but I used the bound issue extensively when assembling the Missing Associates eBook (Missing Associates: Performance Art And Experimental Dance, 2012) several decades later.

Mike: Where did you screen your films?

Peter: In Toronto, I screened them in galleries during Missing Associates performances, at the AGO (Art Gallery of Ontario), or at the Funnel.

Mike: The Funnel began as a series of open screenings at CEAC’s 15 Duncan Street building, did you ever attend one of them?

Peter: No.

Mike: What was the Funnel space like at CEAC?

Peter: It was just an open space, the same one that was used by Crash ‘n’ Burn in the semi-basement of the building.

Mike: Were the audiences different at CEAC events and Funnel screenings?

Peter: I don’t know how many of the Funnel audience made it upstairs to the gallery. Ross McLaren was showing a film of mine called Penetrated (1977) and wanted some promotional copy. I jokingly said, “Just write ‘uncensored.’” After that, we’d see big guys with brush cuts, plainclothes police officers, in the audience. They made it upstairs.

Mike: Were there other places in Toronto where you could show your movies?

Peter: Keith Lock and David Anderson ran screenings in their studio just north of CEAC for a year. There were scattered screenings at colleges. But besides the Funnel (after it became independent), there weren’t full-time venues.

I knew the warehouse building at 507 King Street East well before the Funnel moved into it. A lone sculptor, Mia Westerlund, had a studio there. The entire floor was one dark, empty space, and she used just a corner of it. By the time the Funnel arrived the entire building had been subdivided. The Funnel’s frontage now shows up on the TV series Orphan Black, as a police station.

Mike: How did Missing Associates end?

Peter: Missing Associates did a European tour in 1980. And nothing in 1981. We did our final performance as Missing Associates at the Funnel, in a program Philip Monk curated, called Language and Representation (1982). The performance art scene was pretty well dead anyway. In moving to what is now the CityTV building on Queen West, A Space had been seriously downsized. Lawrence Adams figured that no one was doing anything interesting anymore and closed down 15 Dance Lab in 1980.

Still, Lily managed to find amenable spaces like The Music Gallery, and even gained some acceptance in the dance world, especially in Quebec. That was totally no-go when we had first started out. I’d gone through the performance thing as far as I wanted and was finished with it, I self-identified as a filmmaker. Lily called on me in the mid-1980s to work with her at Pavlychenko Studio on Yonge Street, in two series that paired dancers and visual artists — but we no longer billed ourselves as Missing Associates.

Mike: How did CEAC end?

Peter: Amerigo, Suber and Bruce Eves moved to New York. My contacts with the New York and Toronto groups were infrequent, so what I know of this period is limited. After CEAC’s Duncan Street building was sold, the Toronto group (Brian Blair, Paul Doucette and Saul Goldman) bought a former Salvation Army Hall on Lisgar Street, near Queen and Dovercourt. There was no art activity that far west yet. The building had a magnificent space for performance, but few would ever use it. There was no salvation.

Mike: What is the legacy of CEAC?

Peter: The story of CEAC is a Shakespearean tragedy. It was run by a visionary who did amazing things, then profoundly fucked up. You can’t apply the word Shakespearean to any other arts organization in Canada. I reconnected with Amerigo in New York and he expressed regret that he’d burned his bridges. He even gave it another go, tried to re-do CEAC in New York, but couldn’t make it happen. He did a range of interesting things nonetheless. He created an innovative bookstore called WW3, and even became a high-end restaurateur.

When in Toronto, he had connected with the international arts scene, something that no other organization had yet managed. He cultivated Canadian artists that were provocative, cutting-edge, and equal-billed them with international artists. And he created innovative programming, of which there was very little at the time. Subsequently unacknowledged, Amerigo created a template for arts organizations that followed.

After CEAC went down there was a blackout within the arts media. They pretended that CEAC and artists associated with CEAC had never existed. The only mention I’m aware of is Dot Tuer’s article in C Magazine (The CEAC Was Banned in Canada, 1986). It’s out of print, but searchable online. The CEAC archive at York University is being accessed with increasing frequency. Info is starting to flow back via Europe. Art Metropole just mounted an exhibit initiated by the Polish curators of Villa Toronto, all about the Contextual Art Conference at CEAC in 1976. CEAC was a principal part of the Is Toronto Burning? exhibition at the Art Gallery of York University last fall and winter. (Is Toronto Burning 1977|1978|1979: Three Years in the Making [and Unmaking] of the Toronto Art Scene) The “mainstream” arts reviews still pretended that CEAC wasn’t in the show. Ludicrously, Canadian Art magazine did so while declaring Is Toronto Burning the number 1 show of 2014. But unlike the 1970s there’s now an accessible World Wide Web — bloggers got the truth out.