Museum

Here in this beautiful museum, in the frame where we can come together to perform a kind of public memory. It’s almost like being in the cinema it’s a memory that everyone performs by themselves, and with everyone else at the same time. It’s as if I can only be alone when I come here, when I’m in public. It’s as if the museum were invented so that we could step inside an alternating current of private and public selves. Who am I? Who are we? Who am I? Who are we? And who am I when I am part of this we?

The museum, the art gallery, it’s so many things, but today I wanted to emphasize this quality: the museum is always an archive. What is an archive? An archive is simply a library. Libraries are places where books are stored and sorted so you can find the one you need. But we could make libraries of other things – an archive of T-shirts, an archive of cell phones, an archive of family photographs. This museum, just like a library or an archive, gathers a collection that is stored and displayed. It’s also a picture, this place is a picture of the way that archives used to operate. For many centuries archives were housed in places just like this. I didn’t wake up here this morning. Did you? Does anyone live here? This archive is a destination, part of the picture it gives us of the past – is that there is a space between us and the archive. In order to enter the archive one needs to make an approach, I think we all made some kind of approach today. This isn’t true for the computer archive for instance, but in the old picture of the archive, it was a place you travelled to, and you would arrive at a collection. It could be a collection of books, or sneakers, excellent thoughts, the work of novelists, old movies. A public record.

Does it seem strange to you that we have reorganized our entire culture around the archive? The archive, the library, is so important, so central, that we have invented devices, in fact, a whole array of devices, to ensure that we will never leave the archive again. The archive is no longer a destination, it’s the place we call home, it’s the most familiar place, the most necessary place.

I’m speaking of course about the home computer. Or the smart phone, the tablet, the glasses, the X box, anything that hooks you into the internet. Our new electronic devices ensure that everyone is a photographer, a video artist, and a writer, and these activities are automatically archived, dated, sorted, assembled, in the computer itself, and these archives can be sampled and replayed for others across a variety of platforms. Some of our archives wind up on Facebook, while others wind up in places like this.

The archive used to be as big as this building, now I can hold it in my hands and take it with me everywhere. The archive is mobile, it’s everywhere, it accompanies us everywhere. Oh let me google that. Let me check on that address, that fact, that name. What does it mean to have embraced the archive with such open arms? How has the archive changed our relationships, even the way we live with one another. What difference does it make?

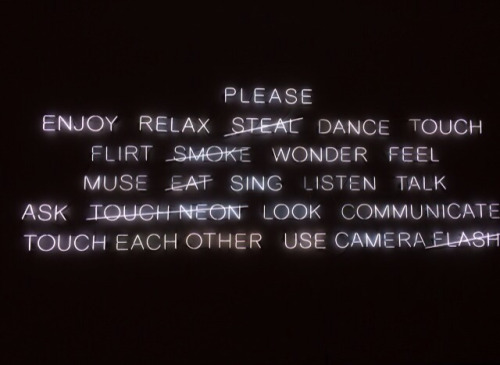

Our electronic devices plug us into archives all over the world. Here is one crucial difference between archives as they used to be, and archives as they are now. We are all part of the archive. Some of the web people are calling this Web 2.0. it doesn’t refer to a new internet, or another kind of internet, but a change in how web pages operate. Instead of operating like a book which you read, or a movie you have to watch, that was web 1.0, web 2.0 is filled with pages that invite participation. You can add comments, or your own videos, your letters, your photographs, many pages are invitation portals entirely filled with contributions by their audience, like Youtube or Flickr, or online dating sites for instance, and all of these sites become archives. It’s the difference between an encyclopedia and a wiki page, it’s the difference between reading a gossip column about stars and checking your Facebook feed. Web 1.0. Web 2.0.

Many commentators have hailed this shift as an inherently good thing. It’s the old dream of the sixties, that everyone could become their own broadcaster – at last we’ve realized that. Web 2.0 means we all have a voice, a place at the table. Some of the academic-type chitchats make an equal sign between user-generated content and having non-mainstream ideas, or progressive values. Now that we’re finally freed from the speech of corporations, now that we can stop protecting and echoing the values of the very richest people in our society, buying expensive records by multimillionaires, or reading corporate news reports sponsored by multinational companies that trumpets the values of the one perfect, now we can see and speak for ourselves, meaning: we won’t be replaying the old power structures. We’re going to create the culture we want, and in this new culture we’re not going to have the old sexism, the old racism, the old power plays. So I’d like to put this to you as a question. Is that true? Just because content is user generated, is it more open hearted, more reasonable, more diverse and fair?

Privilege

Recently, I attended a workshop on privilege, and I realized that at the end of the evening I could step out the doors and not have to think about getting raped. It doesn’t even enter my mind. And that is a privilege. I’d never realized it before, not until I heard several young women talk about it. I spoke with one of the excellent organizers afterwards, her name is Jamilah Malika, and she said: it looks like you’re standing over here, and I’m standing over here, but actually I’m standing way down here, and you’re way up there. Because of this question, this difficult question, of privilege. When I walk into a job interview the person at the other end of the desk doesn’t look up with a startled face and say: Oh I didn’t realize you were… transgender. A woman. That you weigh four hundred pounds. That you’re Palestinian or Jewish or Italian or Muslim, or whomever we seem to be excluding this week.

When an archive is sorted, it seems that there’s always someone being left out. And that can have fatal consequences. Just ask Eric Garner, Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown.

What we perform with each other, and what institutions perform over and over again, is part of a cultural archive. It’s an ongoing created. This archive is usually asked to support whatever group holds power. I mean, the archive is sorted, it is mustered to bring to support to whoever has money and power. This gallery has a director, this country has a president. How many presidents have been women? I’m not saying women are good and men are bad, but if men and women are really equal then shouldn’t half the US presidents be women, and half the corporate big shots and half the artists shown? If that isn’t the truth, then how are we sorting our archives?

Resist

When I use the word resistance, this is what I’m trying to describe. How can we resist this gravity, this tendency, to reserve the front of the room for white guys like me. If we have user-generated media instead of corporate media, if we have wiki pages made by you and I, the people, is that going to create a society that is more fair, more inclusive? Or we could ask the question this way: how are we, all of us together, going to create the archive, and then what are we going to do with it? We, all of us together, are already building the archive, we’re busy emailing and texting and making photographs, movies sometimes. I think what I’m trying to suggest is that politics isn’t reserved for the voting booth or the newspaper, it’s also there in the comments column, in your facebook posts, in everything you buy and everything you don’t buy. Purchasing something is a way of voting. Am I going to vote for the multinational corporation, am I going to vote for the mall, for the chain store, for the mom and pop grocery store, for the brand and the logo.

As we know from Mr. Snowden – are you allowed to talk about that guy in this country? – as Edward Snowden made clear, your government and mine is deeply engaged in the question of the archive. The library of information. Almost all of the revelations, the whistleblowing, that Mr. Snowden has done, is very simply pointing a finger at how the government has changed its relationship to the archive. The old model of collecting information was to select a person, a group, an area of concern, and then you have people, government information collectors, who go out and dig up whatever information they can. They might do this by asking questions, or opening someone’s mail or tapping their phones, they begin to gather information, they begin to create an archive about that specific situation. Your government, it turns out, and every other government, has been in the business of creating archives from the moment it is born. And those archives, those libraries of information, are usually aimed at their own citizens, their domestic populations. When the Occupy Movement began four years ago, when the civil rights movement was working to create equality between blacks and whites, when the women’s liberation movement fought to create equal wages and equal treatment, not to mention voting rights, when factory workers tried to unionize at the turn of the century, the government was always there, gathering information, getting down everyone’s name, taking photographs, creating an archive. The archive is a way of keeping control, and often it’s the basis, the ground for further action, sometimes murder, or being arrested and jailed, or losing your job.

What is the brand new way of creating archives today? What did Mr. Snowden tell us? Individually, we are all working with small computer machines that create their own archive. Your emails, your photographs, your favourite songs. The new aim of the state is to gather all information, everywhere. Every keystroke, every website you’ve ever visited, every email you’ve written and received, every textmessage and tweet, Instagram photo, Google search, everything that is done on the computer should be part of a single state archive. A total surveillance society means that all of our small archives are chained together in a single vast and unending archive.

We could have a debate about whether or not this is OK. But first tell me: how many people here voted for the internet? Were you the one who said OK to that? What about the atomic bomb? Did you vote for state surveillance? I was staying with a friend in Geneva a few years back and they were going to vote on this huge building downtown and what was going to be done with it. There were a few proposals, maybe it could become a school, or a waste recycling facility, anyways, everyone who lived in the city was going to vote on it. It seemed so: democratic. Does that seem like a crazy idea, that we could vote on things that actually mattered to us.

Anyways, back to the archive. Instead of highlighting an area of concern and digging up information, the new approach is to gather all of the information, and then… and then you have a problem. It is a problem that is very particular to this moment, to this time. It is the problem of too muchness. How do you navigate through those vast quantities of information, all those web pages, all those selfies. How does one begin to sort through all that?

How do you do that at home if you’re working on a text document? Could you imagine that a text document is a small archive, that it is an archive of words and sentences? What if you need to find a passage in a text document, in a letter you want to remove those harsh words to your former boss, so what do you do? You go to the find function, you go to the search function, you type in some keywords and then you are directed to certain portions of the text. This is how we navigate the data oceans of words.

The system works pretty well when the archive is like a library, when we are dealing with the world of books, or texts or emails. But a lot of the web content isn’t text based. A lot of it is audio recordings, or pictures. How do you search through a library of pictures?

Metadata

The answer to this question is a word you might have heard in the news a lot in the last year or two, the answer is: metadata. The way you sort through pictures is via metadata. This is data or information stored with the picture, it’s bundled along with the picture or sound, and might tell you something about what kind of file type it is, a .jpeg or a .tiff, it might tell you, if you use a fancy camera, what your shutter speed, your f stop is, it might tell you about how much contrast or what kinds of colours are in the picture. These informations are part of the image file or the sound file, and the hope is that this metadata will develop so that we can sort through pictures with increasing speed and efficiency, that we would be able to quickly locate a face or a gesture.

I want to find every moving image that shows someone opening a refrigerator. I want to see the look on every face in a home movie when they enter a room they’ve never seen before.

I’m thinking now of two people, perhaps you can already tell. I’m thinking of the men and women collecting information for the surveillance state, but I’m also thinking about the artist, who will have at her or his fingertips, every picture and sound ever made, in fantastically high quality. And you will be able to sort through all these pictures as quickly as finding a word in a word document. As an artist you will be able to access everything, and to sort through everything. Does it mean that no new pictures will ever need to be produced, that the art of the future will be an art of arrangement, in other words, an art of relationships? Part of what I can imagine artists doing is to create this metadata, to turn this ocean of information into roads that we can all travel on.

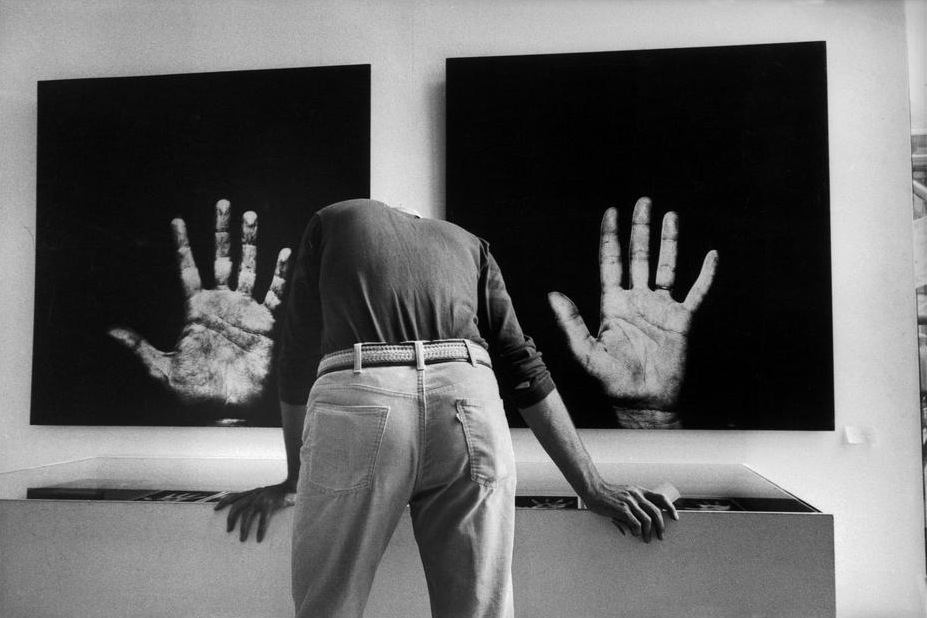

Body

The first archive is our own bodies. This is where we store genetic information, cultural information, information about who we think we are and how we should behave. When we step into a room like this we can instantly recall, without even having to consciously think about it usually, that there are other rooms just like this one where we’ve already been. Oh look, there’s seats laid out, one of those seats must be for me. We activate our archive, we process the information in a flash, we take our seat. And then we do this strange territorial thing, because a moment earlier and we’re still looking out and thinking where am I going to sit, but as soon as we sit down it’s like: this is my seat. We own a piece of this room, it’s all mine, don’t ever ask me to move.

Can you imagine walking into this room and feeling that you couldn’t take one of those seats? What is it that happened to you, what would your archive look like, if it relayed this information to you: you don’t belong here. Maybe some of you are already feeling that. I don’t belong in this space. Our archives can give us a chair in the room, but someone else’s archives can take that chair away.

The first archive is our own bodies. When I look across the room today I can’t help noticing that nearly every person here is leaning, leaning, on one side or the other side. And when I meet up with people, I notice that even if they’re standing up and talking to you at a party, or you’re sitting together with them at dinner, they’re leaning over to one side, maybe just slightly, maybe a lot. What this means is: one side of the body is collapsing. Oh, I can’t. It’s caving in. All of the organs, the tissues, the muscles, they’re all collapsing on one side. And when you get to know someone, you’ll see that we’re very consistent. Over and over again we collapse on the same side. You could even say, to use language I’m not entirely comfortable with, that all of us have internalized a kind of personal credo and belief, that we have a good side, and a bad side. We have a strong side, and a weak side. If means we wear out one side of our shoes more than the other, it means that out of the archive of our experience, the collection and replayed memory, what you are doing right now, in this moment, in this instant, is performing the archival preferences of your body. Because you fell when you were five years old and your body keeps remembering, keeps returning you to the crash point. Because somebody hurt your heart. Because the person you trusted more than anyone else in the world called you a name that you haven’t been able to stop calling yourself, and it happened from one side of the body.

The body is a living form of memory. I’m not saying this metaphorically, the body is made up of memory, when you get old and your hips start giving up or your knees hurt or you develop arthritis, or even when you’re born you have certain features, certain traits of the body that actually belong to your father, or to your grandmother, or to your grandmother’s sister, because your body is remembering their body. Oh you have your mother’s eyes. Our genetics are a physical form of memory. An embodiment of memory. And that can make sexuality such a charged arena, because someone’s touch can bring back moments, responses, unwanted encounters.

Our body, like the body of the state, has a ruling class and an underclass. There are parts of this body that we can’t even feel, that have been ignored or left behind, that aren’t being looked after. And there are other parts of the body that are always up front, it’s our game face, let’s put our game face on. I’d like to pose to you the same question, the central question for me in relation to the archive. How can we develop a relationship to this archive that can open to the difficult and unwanted parts of our bodies? How can we live in our bodies in a way that isn’t always voting yes for the old hierarchies? How do we bring the old habits into focus, into the arena of attention, how can we begin to notice how we are treating this archive? Because if we can’t treat the archive of this body in a different way, if we can’t wake up to the archive of this body, then how are we going to wake up to the archives in our computer extensions?

Lost

I was having a conversation with a friend recently, and like many conversations these days, it was happening online. We were never face to face, we haven’t lived in the same city for years now. There are certain moments of this conversation that we wanted to extract and use as the basis for a new piece of work, perhaps a novel. The novel, it’s an old form, and it began as an exchange of letters. And my friend asked me this question: do you have all the mails? I just don’t want to lose things.

He asked me a question, and then I did this really frustrating thing, which is to answer with another question. How do you lose something? Today, even the messiest person in the room, the one who can’t find their excellent brown t-shirts, the one who loses underwear, socks, hats and gloves, the one who never washes the dishes, they can’t seem to lose anything on their archive machine. They open their email program oh look, there’s every email they’ve ever written, all in order, and you do a name search and then all of the mails to that person just come right up.

There is an unprecedented mania for order at work, at the heart of those little machines, at the heart of our new digital lives. It speaks to an anxiety that my friend expressed so clearly: I just don’t want to lose our information. Why would we go to such lengths to produce archives of even the smallest items if we weren’t terribly afraid of losing something? Why this crazy mania for order?

It makes me wonder. What is it that we are afraid of losing? Or even: what have we already lost? Are computers the sign that we have lost something precious to us, something we used to have? Perhaps we used to think of this absent piece as part of our home, and now that it’s gone missing we have machines that arrange every last detail, deliver us to every decisive moment, except the one that really matters because it’s already gone.

The question the computer keeps solving for me, whether I want it to or not, is the question of getting lost. It’s so hard to get lost, to lose information, to lose your place, with a computer.

Lost 2

But wait, wait. What about the laptop that got run over by a car. What about the Iphone that I went swimming with? What about the Xbox that I dropped off the balcony? It saved every thought I had, carefully catalogued every gesture and photograph, and now it’s gone. This is the other side of the self-surveillance machine. It contains your whole life, but because it’s a product of a capitalist system, as soon as you buy it, it’s worth half of what you paid for it, it’s instantly obsolete, soon it’s worth nothing at all, and although one day this machine contains everything, the next day it’s trash. It’s as if you owned this entire gallery only to wake up the next morning and it’s gone. That’s one of the new features of the digital landscape. You’re a one or a zero. You’re all there, or you’re not there at all. Either you can never get lost, or you were never there at all. Some archivists believe that this period, which is a moment when the archive is held out to be an essential good, will produce little that survives, because information exists only in such temporary forms.

I’d like to indulge in a moment of nostalgia, please forgive me. There used to be a few central places in the life of a city that acted as hubs, meeting places, centres of resistance. It’s where new identities could be formed, new thoughts arrive. I’m speaking of course about record stores, book stores, coffee shops. Of course the book and record store functioned as gateway drugs for new capitalist consumers. But it was also a place where you could get lost, wandering through the stacks you could find what you weren’t looking for. When you think back on the decisive moments of your life, when you met the person you fell in love with, when some strange idea came to you that turned into your first novel, or a sentence you never pronounced, do these decisive moments arrive because you sat down and planned it all out in advance? Or are we, as the Canadian poet Leonard Cohen said, are we on the front lines of our own lives, trying to fail better, picking ourselves up off the floor. Aren’t we wandering through the stacks of our lives hoping to find what we aren’t looking for? Isn’t that the most important thing we could possibly find. How did you meet your best friend, the one who you can talk to about everything? Today the bookstore and record store are specialty items, largely replaced by monopoly capitalism. So the question is: how can we get lost? How can we use our archives to get lost in a fruitful way, in a productive way, so that we can find what we aren’t looking for.

Compression

Let’s look at a last important aspect of the archive. Every book, every movie, every narrative painting here is a way of condensing, of shrinking down and summarizing the many experiences of a life and putting a frame around what we might name as the decisive moments. What would the movie of your life look like in nine scenes, if you could only film in nine different rooms, who would you put in those rooms, what would be happening there? Those nine rooms would have to stand in for all the rest, for all the rooms we don’t have time to watch. How long can you watch for – five or ten seconds for a commercial, two hours for a feature film, many hours when you’re binging on a new TV series perhaps. But digital storage is becoming very cheap, soon it will cost nothing at all. And this means that we don’t have to make a decision about what scenes in your life you’ll be able to film, you can film every moment, from multiple angles even. You can live and record your life, in “real time” as they used to say. If you’re twenty years old, you can have an archive that lasts twenty years, documenting every moment, waking or asleep. The technical term for this is compression. We are quickly arriving at a moment when we won’t have to compress our recordings, when everything around us will be available to us as an image.

The question is: what kinds of new possibilities does this pose for the artist, and for the audience? Not just a new kind of art, but a new kind of audience. Linking, sorting, navigating a flow of pictures and sounds.

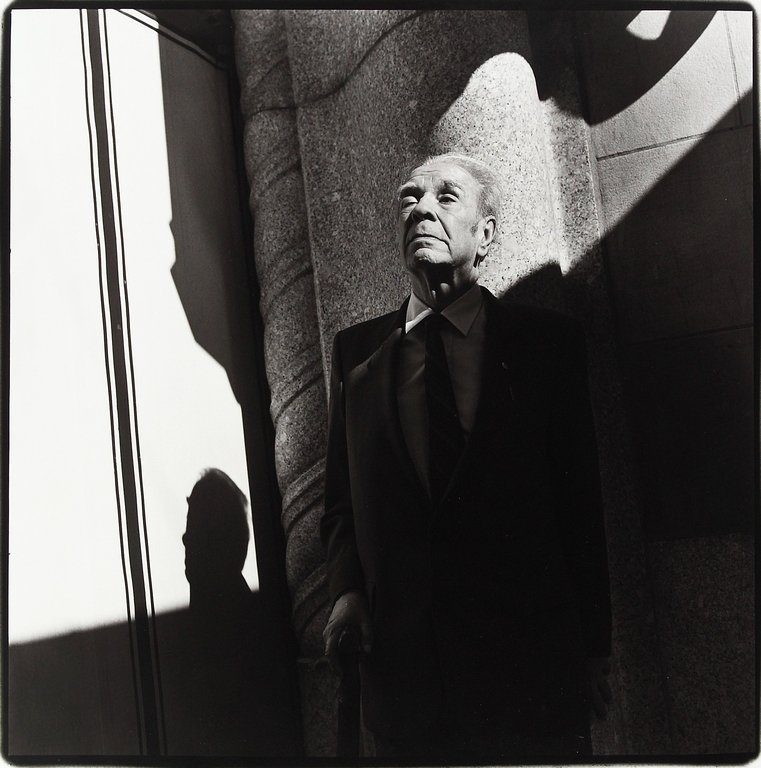

Borges

I’d like to leave you with a picture, which arrives via a very short story by Jorge Luis Borges, the glowing Argentinian writer. He wrote this story in 1946, a year after the world had finished tearing itself up in a global war because some countries were trying to change their borders, change their maps.

On Exactitude in Science by Jorge Luis Borges,

…In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast Map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.

A map that is the same size as its territory. Welcome to the archive.