Invisible Pictures: The president’s blue jeans and the secret of the atomic body

Nashville

I wanted to talk about pictures, in part because I’m here in Nashville, a city that everyone knows, all around the world, the same way we know all about Baghdad, or Kabul, or Ho Chi Ming City. We don’t need to actually visit these cities, we see them over and over again, in what they still call, in a surpassing moment of ‘irony,’ the ‘news.’ So when my plane touched down, and that comforting southern drawl said, “Welcome to Nashville,” I felt like I was home, because there is a Nashville that already lives inside me, as a picture, a picture of Nashville. Though I knew that it might be difficult to see you, to come here and look at you, because I would be so busy holding up this picture of Nashville in front of my face. You might also be busy, telling me things about your life, the hope that you still have, you could be showing me your hope, I mean, the one thing you hope for beyond everything else, and I just want to apologize now because I can’t be sure I’m going to be able to see it. I’m looking at you, right now, but I’m looking at you through my picture, my picture of Nashville, my Nashville. The picture is so strong, so clear, it makes a lot of what is around me invisible. Have you ever noticed that? This is what my picture does, it erases people and conversations and ideas that don’t fit into my picture. My picture of things. And please don’t take my words to mean that it’s only happening here, that these pictures only belong in Nashville, because when I’m home I have a picture for that place too, and I am busy, I am working day and night, holding up my picture of home, and it shrinks the world I live in, it provides a frame for me to see through. Let’s be clear about this. It’s what makes love possible.

Private and Public

I wanted to talk about pictures. Perhaps we could start with a picture of someone we all know, your former president for instance, Mr. Bush. In the past, pictures were only made of kings and queens, but today we have the possibility to make pictures of each other, ordinary people doing ordinary things. Private pictures for instance. But even when some particularly devoted parent snaps away at their new child all day – oh look, she moved her finger, again! I think it’s clear that there are a few people in the world that have their picture taken all the time, they are like those old kings and queens, they are the aristocrats of the picture world. It is difficult to move around a place like this, a place like Nashville, without tripping over these pictures, without seeing these glamorous, powerful, rich, beautiful people staring back at me with their newly adopted children, their new perfumes, their new government policy.

Perhaps we could say that the pictures which seem to be everywhere are broadcast, while the pictures we make of each other, are narrowcast. Tell me, the pictures in this museum, do you think they’re more like broadcast, or more like narrowcast?

Mr. Bush

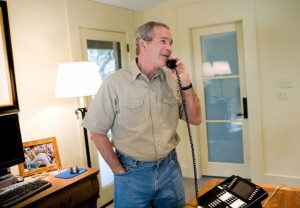

But let’s begin with a picture of someone we all know, your former president, Mr. Bush. In this picture he’s off duty, though for someone who is pictured so regularly, for the kings and queens of the picture world, there is no gesture, no matter how intimate or private, which is not a pose. But here he is on the weekend, and he’s at home, he’s down home, in Texas, on his ranch, and he’s hanging out with a few friends. He’s smiling. We don’t know what they’re talking about but it’s a good time, an easy time, or at least: it looks good, and in the world of pictures, looking good and feeling good are the same. It’s a real picture, and when I saw it there was one thing that really stuck to me. I’d like to share that with you, the thing that stuck to me, but first I’d like to talk about what that means.

There’s a lot of pictures in this world, this world of Nashville for instance, your world, I wonder how many pictures you’ve already seen today. But more than that: I wonder how many pictures you didn’t see. We are surrounded by pictures, they are flowing through us right now as electro-magnetic waves, they are forming and reforming on computer screens and TVs and satellite broadcasts all over the city, in apartments just down the street. We can’t remember them all, we can’t see them all. Imagine if you had a perfect memory, you could walk down a single street, perhaps the street that you’re living on right now, and you walk until you reach the door of your house, and the experience of each moment, each instant, would be so deep, so intense, so rich, you could spend the rest of your life savouring those moments. They say that Wittgenstein’s memory was so fine he could hear a piece of music, even a symphony, just once, and he’d be able to hum every note. But what about my ordinary attention? Why is it that some pictures arrive, while most pass unnoticed, even as I’m looking at them. Even as I seem to be looking at them, staring at them, reading them, trying to understand them… they’re disappearing. Why do some pictures stick, and others don’t? Of course I don’t really know the answer to this question, but there was a Frenchman who mulled this over a few years back, his name was Roland Barthes. And like all important thinkers he was urged by something very personal in his life, for Mr. Barthes it was the death of his mother. It was the death of his mother that led him to look at what remained of his mother, what was left was her pictures, her photographs, and from there, he began to write a secret history of photography which he called Camera Lucida. He was also concerned about this question: why do some pictures stick, while others pass away unnoticed? He said that some pictures have a special quality in them, a thing, which made you remember them. Is it a magic potion, is it a formula, some trick of the light? He called it the punctum, he said there might be a moment in a picture which hurts you, he said there might be a moment in a picture which hurts you to look at, and he called that moment the punctum. Without that moment, the picture disappears. Is he right, is he wrong? From the grief over his mother, it’s what he said, it’s what he brought forward, for us.

So let’s go back to this picture of Mr. Bush at his ranch, laughing with his friends. What is it about this picture which sticks to me? What is it about this picture which hurts me? I have to admit it. It’s his jeans. It’s his Levi 501s. Why do his jeans hurt me?

Is it because they used to make jeans in America? There used to a huge garment industry here before free trade wiped out all those jobs, which all went to underpaid workers in the Philippines and India. The bad working conditions, the bad pay and environmental damage, those go abroad, while here at home there’s unemployment, which means that the price of jeans stays low, and that’s the important thing, right? As long as the shareholders make money, that’s the most important thing, right? And the jeans that Mr. Bush is wearing are a symbol for why the low cost of jeans is really a very high cost.

I wish I could tell you that’s the reason why Mr. Bush’s jeans hurt me. But that’s not the reason. The reason is much simpler than that. It’s because I have jeans. I went out to the store and saw them on the rack after rack after rack of denim and said yes, that’s me, those are my legs, that’s my denim, and I bought them and took them home. Those jeans are my home, so what are they doing over there, in Texas, being worn by Mr. Bush? I know why he’s wearing them, or at least I think I know. He’s a multi-multi-millionaire of course, he’s a former oil executive, he comes from a family of great wealth and power. And I don’t know the folks who are standing around him, but my guess is that they are also multi-multi-millionaires. And they’re all wearing jeans too, jeans and smiles. Denim smiles that seem to go on and on. The jeans say: hey, I’m a regular person, I’m just like you. I’m a multi-millionaire, all of my friends are multi-millionaires, I have a maid who cleans my house and there’s a dude whose only job is to drive me around in one of my many cars. I have personally authorized the warantless wiretapping of millions of American citizens, but hey, I’ve got my Levi’s on. I’m just a regular guy.

His jeans hurt me, they made the picture stick, and after I saw it, I never wore jeans again. Childish I know, what does it solve, what does it prove, what does it change? Nothing. But I just couldn’t be part of that picture. You know?

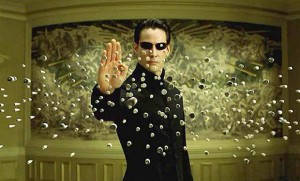

The Matrix

Last night I was indulging in an old pleasure of mine, I was seeing a movie I’d already seen. One of the great joys of watching a movie you’ve already watched, is that you’re not so blinded by the plot anymore. You already know what’s going to happen, so you start noticing other things, details in the background. Hey, look at that beautiful… couch. That night table. The wallpaper. Look at the way her face turns into the light. She doesn’t have to say a word and I can feel that face, I know her. Inside that light, that special light that seems to come from somewhere inside her skin, I’m already becoming someone just like her, just by watching.

Yes, last night I was watching a film I first saw in a big movie theatre filled with awestruck teenagers. It was called The Matrix, you’ve probably seen it yourself. It’s set in the future, and of course, for all these teenagers, almost everything is the future. Almost every movie, no matter how old it is, looks like science fiction to them. But for me, as old as I am, and so much younger than every one of them, this movie looked like the past. And by the past I don’t mean the handsome, poreless cheeks of leading man Keanu Reeves, or the good old fashioned sexual repression in the movie, the way that bodies in this future are pored into overcoats and trussed up in black leather and then released only in a series of ecstatic, delirious shoot outs. If only they could go on forever. If only I could be a teenager forever. But that’s not what felt old to me, exactly. Do you remember the film at all? There’s a battle between humans and machines, and in a last desperate move the humans destroyed the sun to rob the machines of their solar power. The machines found an alternative power source by harvesting humans, putting them into large energy farms, and then building this complicated computer program which makes all these humans, who spend their entire life in a small watery tank, it makes them think that they’re living a life out here, going to work and falling in love and going to art galleries listening to foreigners from Canada. But the reality is that they never leave the tank, and all this, and I mean every building, every restaurant and home and automobile and every bit of clothing, that’s what they call The Matrix.

Can you hear that already? Can you hear what I hear?

This struggle between humans and machines, we know that already, right? We’ve been hearing about that for decades. And it’s been dressed up and reframed and rebranded a thousand different ways,. It’s 1984, it’s 2001, it’s The Attack of the Clones, it’s Star Trek, it’s Lost in Space. It’s the future which has already happened.

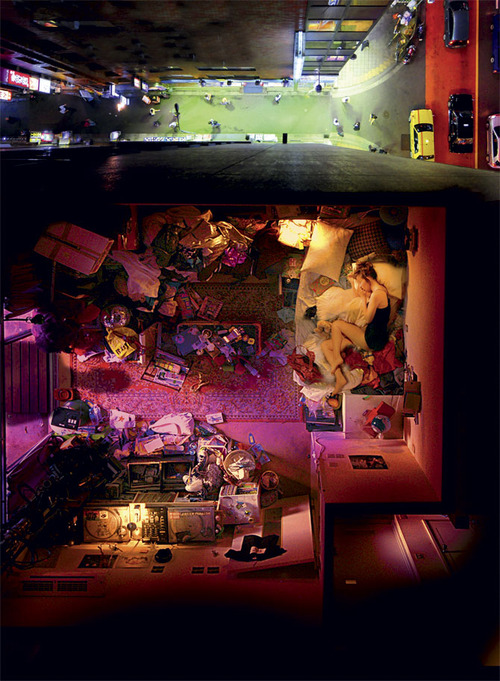

Walking to School

Could I share another picture with you? You’re seven years old and you’re walking to school, the way you walk every day. Now the thing about your walk is, that at the head of your street you’re going to turn right, and the elementary school that has been entrusted with your education, is waiting there. But if you turned left, and headed down that road a little ways, there was another, larger school, a high school, where kids of unthinkable stature are busy moving towards. Because you’re seven years old, those kids are like science fiction, like the future. And when you look at them you think, no, not me, I’m not going to act like that, I’m not going to do… that. Isn’t it the same story you’ve been telling yourself your whole life: I’m never going to grow old. And on my death bed, and just before my last breath: No, not me, I’m not old, I’m not getting older. I’m not dying, am I?

This is the picture. You’re seven years old and you’re walking to school, and you’re just about to take that right turn which will admit you to the schoolyard, and all of its special terrors, but before that happens there’s a crush of teenagers heading in the other direction, moving quickly towards that other place, that other school, which you’ve never set eyes on. One of these teens is so tall you might as well call him a man. He’s skinny like a kid and he’s got glasses and a sort of serious look and because you’re seven years old, you’re invisible to him. In fact, you’re always invisible to these teenagers, you might as well be a hundred years old, or no age at all, because no matter what you do, no one notices you at all. So the man-boy walks fast right up in front of you and he’s carrying what looks like shoe boxes, a whole stack of them, and because he doesn’t notice you, because no one cares what you see or do, you stare at him and his precious boxes, wondering what’s inside. And you also see the small divot, the small depression in the road, which he can’t see because his arms are piled up with boxes. You wait for it, you know what’s going to happen, you’re already in the future, waiting for him to catch up to you, and then his foot hits the small pothole and he throws his arms up to break his fall, and the shoe boxes fly away from him and scatter on the road. And when they do, you can finally see what’s been kept hidden all this time. For a moment everyone stops moving, you’re all watching him fall, and then he gets up because he’s OK, and you start breathing again as he begins to gather up his cargo. It’s not easy because what’s spilled out of those boxes are hundreds of small cards, individual pages, which are a little stiff, and you can see, squinting hard, that each card has some holes cut out of it, and lines of numbers. They’re not in order any more, that will have to wait until later, but he gathers every last one and you don’t help him, because you’re invisible, remember, and invisible people don’t help teenagers, not where you come from anyways, so you wait until he’s done, and then he goes to his place, and you to yours.

What he is carrying, of course, are punch cards for computers. Cu-Com-Com-puters. No one owned a computer then. There, that’s how old I am. And the ones that could do more than add five plus five and make it equal ten, were the size of football fields, were the size of this entire gallery, and these computers used an awful lot of cards. Cu-com-computers. There was actually a moment before the computer, I mean, before we let it enter us. Before we allowed it, inside. Before we became people who were used by computers.

Tell me, this is the cradle of democracy, isn’t it? When exactly did you vote for the computer? Or Styrofoam cups? Disposable forks and knives? The atomic bomb, when did you vote for that?

Let’s go back to our picture. It’s a picture of the threshold. We haven’t done it yet, we haven’t voted for the computer, yet. It’s not everywhere. There’s the internet, but only the Pentagon uses it. You know that the internet was designed so that when the next bomb drops, there would still be a way to communicate, when everything else failed. After the world ended, there would still be the inter-net, and a few bankers I guess, that’s who gets saved in this country, isn’t it, the people who are running Goldman Sachs and Citigroup and the bank of New York Mellon. I know what you’re thinking. It’s too bad those sons of bitches didn’t live in New Orleans, because if they did, those levees, which to this day, have never been rebuilt properly, would be high enough to withstand any kind of flooding and hurricane, and no one would have to die because they were black or poor. You could use these bankers as human shields, but I’m getting away from the picture, the corner of the road, the intersection, the crossroads, and what we are witnessing there, is a body, clumsy the way bodies are always clumsy, the meat moving and shaking, the body and all that paper, heading towards the machine, heading towards the place where this body will be able to service the machine. And there’s a pause, a small moment on the road. He’s still going to his school, you’re still going to yours. The revolution of the machine, it’s unstoppable, but for that moment, you can pause and take stock. What is he carrying exactly? And what we will have to carry after him? What are we carrying now?

Could we take this simple picture, this picture of an accident, and put it next to a picture from The Matrix, that smooth high-tech world of shoot outs, where the great war between humans and machines are being fought. When you rub those pictures together, tell me, do you feel that friction, that heat, somewhere down the length of your spine?

Did you vote today for your computer? Did you make a picture of yourself, for yourself, hunched over the screen? Do you remember that moment in The Matrix where they’ve trapped Morpheus (played by Lawrence Fishburne) and drugged him and they’re waiting for him to spill the secret codes so the machines can go to the last city in the world, the last city that still has people, real people in it, that don’t live in little tanks. The machine is talking to Morpheus all the time, it’s taken human form, of course it could take any form it wants, but here it looks human, it looks like it belongs, like it’s part of The Matrix. And the machine says that humans use up and destroy everything they come into contact with. The machine says that humans are a virus on this planet, and that machines, these super computer machines, are the cure for that disease. The disease of humans. Do you remember that part? When I heard the machine say that I closed my eyes for a moment, and I stopped seeing those perfect Hollywood bodies in their perfect leather suits, I saw a workplace, which looked maybe a bit like the place that you go to work, every day, and I saw women and men sitting down in this workplace, and every one of them, without exception, had this in common. They were all, we were all, busy, using our computers. We were opening, letting them enter us. We were becoming like them.

Atomic Secrets

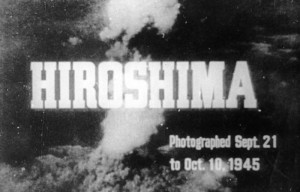

So tell me: all those movies. All those old battles between humans and machines. Has it already happened? Have the machines won? What kind of picture are we making, when we huddle next to the glow of the monitor, when we look into that steely light? Or is this just another version of the railroad, the telephone, the atomic bomb? Didn’t those change everything? I mean, not just the invention of the bomb, but the fact that it was used. It was dropped from the sky, and not just on one city but on two: first on Hiroshima where it killed 70,000 instantly, just like that, and within 5 years, 200,000. Three days later it was on to Nagasaki where the second bomb killed at least 45,000 people instantly. Can you make a picture of that? I know I can’t, it’s just too many people. It’s a number, an abstraction. I keep it far away where it can’t hurt me. There is no punctum in that number for me.

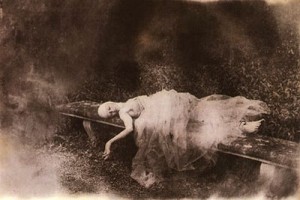

You know the Pentagon sent in soldiers right away, and they weren’t carrying guns they were carrying cameras, motion picture cameras. They fly a plane over your country and they drop this new kind of bomb that kills almost everyone, and the ones it doesn’t kill go to the hospital to die, and then they send men to make pictures to see what the survivors look like. It’s just science, right? It’s just evidence and observation. Those pictures, many of them showing young children terribly burned and scarred and dying, are filled with the punctum. They are filled with moments which hurt you to look at, in fact, like all wars, they are unwatchable. They are too much.

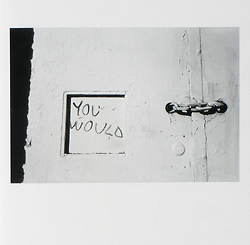

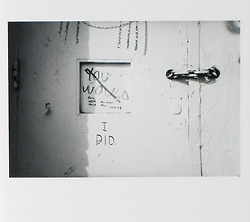

You know what they called the point on the ground directly under the atomic blast? The hypocenter? In both cities they called it the same thing: Ground Zero. The pictures which were made in that place by the American conquerors were kept secret, no one saw them, they was a big secret. Instead, in the years ahead, there was a very large and calculated campaign to offer us, to offer all of us, a picture of the atomic bomb. Tell me, when I say the words together “atomic bomb” isn’t there a picture you already have, that great white mushroom cloud billowing up in the sky, or across the desert, filling the horizon. Tell me, don’t you see what I see? All that smoke, all that sky. It’s a picture, like the glossy pictures of The Matrix, which has been carefully stage managed, rehearsed, organized, choreographed and controlled. The most important part of this mushroom cloud picture is what isn’t shown. Because this picture, like so many of the pictures which surround us, is busy keeping a secret. In fact, the reason why this picture was made, was not in order to show or demonstrate, but to keep a secret. What the picture shows is the power of science, the immensity of the explosion, but most importantly, the up in the air abstraction. It is the picture I used to have of the atomic bomb, until I asked to borrow an uncut reel from the Museum of Modern Art, where you can see some of the footage that was made days after the attack, showing real people, real men and women and children, many of them forced Korean labourers, whose bodies have been torn apart. My picture of the atomic bomb is a picture of the body, and this is exactly what is being kept secret, what is kept hidden, what must never be seen or spoken about, in the pictures of the atomic bomb.

Ground Zero

You know what they called the point on the ground directly under the atomic blast? The hypocenter? In both cities, both Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they called it the same thing: Ground Zero. So imagine my surprise when I heard these words again, hardly fifty years later, being used to describe the attack on the Twin Towers. Wikipedia says that it was CBS reporter Jim Alexrod who broadcast the word, but that it had been graffitied into the sidewalks of Manhattan since the 1980s in a series of markers that indicated the distance to the island’s financial district. Ground Zero. These words are also a picture. And this picture, I’m sorry to say, is also a picture which is busy covering something up, even as it attempts to show something. Like so many of the pictures which are around us. When the atomic bomb hit, the blast was so intense that people were obliterated without a trace, they literally disappear. There are no bones, no teeth, nothing. Imagine if you were asked to stand up, right now, and you were asked to stand together, very close, very tight, because we were going to fill this building up like a cup of water, fill it to overflowing, until there were people standing from one corner of the room to the other, and then in every room. And then imagine you were all disappeared, just like that, in an instant. You’re there, and then you’re not there. When I hear the words Ground Zero, the words which are also a picture, I see thousands and thousands and thousands of Japanese and Koreans being disappeared, vanishing underneath the twin towers.

We never dropped that bomb, we never burned those children, we never saw those pictures. It wasn’t our science, those aren’t my jeans, that’s not my president.

Love

You know what I wonder, sometimes, there’s this picture of love that has followed me around, I think maybe it’s been following you around too. And in this picture he looks at her, or she looks at she, or him at him, and they have a special beautiful light on their face, the ones who are about to fall in love. Oh yes, they’re the most perfect people in the room, they’re standing at the most perfect moment in their life, and they’re both there, they’re both way up there, on some kind of Olympus of love, so it’s clear, it’s obvious they were meant to be together. Didn’t I see both those names before the title of the movie even? That’s the picture of love that keeps following me around everywhere I go. Well I don’t about you, but I don’t get around to visiting Olympus so much these days, so I can’t help wondering if it’s possible, maybe it’s just possible to fall in love in the other place, I mean the place of the imperfect, the broken place with the cracks where the light comes through, to find the other person not when they’re the flash of the party, not when they’re the wittiest, smartest most beautiful person in the room but when they’re small and lonely and afraid, just like you. Could you love them, could you love yourself, at that moment too?

Imitations of Life

You know how sometimes when you’re reading a book, when you’re so far into it, it seems to be reading you, and you think, “Never again will another book need to be written. This is the reason language was created.” I have just finished a novel by the glam American writer Nicole Krauss, or should I say, it’s just finished me off, and amongst its many memorable lines is this one: The truth is the thing I invented so I could live.

Imitations of Life. Imitations of love.

After my sister gave birth I had, very unexpectedly, a young boy in my life. “If I make movies instead of children, does that make me less human?” Godard asks his partner and collaborator, his co-writer and co-director. But not his wife, not the mother of his child, never. There are movies to be made, and movies take time, they are time machines for all who enter them. No time then for the biological time machines we call children.

I loved being around him, my nephew, my Jack. I loved the fact that he didn’t remember anything, that the past was entirely useless. There is only now, right now, and he managed, like all children, to have a restless capacity to invent the present. And we would go down the street, and just because he was little, just because he couldn’t walk or talk, perfect strangers would look at him just for a moment and light up. He would make them better people, he appealed somehow to their better nature, and he wouldn’t have to do a damn thing. He was just a kid, and what a magical quality this is. Can you imagine being an adult and having the same effect? You would walk into a room, it doesn’t matter where, and absolute strangers would grow brighter and kinder and more generous. Can you imagine a place like that where we would allow children to teach us what they know and demonstrate every day, even as we are busy cornering them, and closing them off, until they are caught in the prison house of adulthood. Tell me, the cruelest word in the English language? Isn’t it: adult. To be an adult. The lie we live every day, the empire we swear allegiance to, long after it’s sun has set.

“If I make movies instead of children, does that make me less human?” I started thinking about movies differently after hanging out with my nephew. I knew that all too soon he’d be stepping into them, and they’d be filling him with their longings and their hopes, and ideas. The electronic babysitter, the guitar heroes and kill games, he was already keening for every last pixel. That’s when I started work on the movies that are part of this exhibition. The longest movie, Imitations of Life, gathers a number of science fiction moments. Like all the pictures which are important to me, which I cherish and hold dear, I didn’t make them myself. They are borrowed and received, like the words I use. These words, this trail of language that I’m leaving behind here, are not words that I invented. They’re not words that are being used for the first time. If they were, no one would understand a thing. And all the words you use, even to describe your most private and most personal experiences, those aren’t words you invented. Others have been there before you, and even though it feels like you’re making it up as you go along, hey I’ve never been here before, no one’s ever touched me like that, no one’s ever looked so long into my face. I never say the words for the first time, instead, I repeat. Do you take this… to be your? I do. I love you. I’ve had enough. I can’t, not like this anymore. Stop. I repeat, my words, and the emotions my words make possible. And with pictures it’s just the same. The pictures I use don’t come from these hands, they arrive, like the words I use, they arrive and they enter me, until it seems like, until it feels like, they’re my pictures.

There is a moment at the end of a book which I might as well confess that I never read, I skipped right to the end, knowing that this cherished, beautiful moment was waiting for me there. It offers a well known, even clichéd picture. You could imagine yourself in this picture. There’s a person, let’s say it’s you, and you’re walking on the beach. The sun is sinking into you, filling you, warming you. You’ve decided to walk close to the surf, so that as you make your way, not in any hurry at all, no need to get anywhere, to arrive at a destination, but as you make your way the water laps up onto the beach, and washes your footsteps away. At the end of the book there is this famous line: Humans are an invention of recent date. And one perhaps nearing its end. If those arrangements were to disappear as they appeared… then one can certainly wager that humans would be erased, like a face drawn in sand at the edge of the sea.” Like your footsteps, for instance. What we recognize as human would be erased, like your footsteps.

But wait. What does the writer mean by: those arrangements? “If those arrangements were to disappear?” Perhaps the way you put one foot next to another, as you make your way along that beach, perhaps the way that I organize my words, is what we like to call our personality. The arrangement is my personality. And if these arrangements were to disappear… How does he put it? “Like a face drawn in sand at the edge of the sea.”

Imitations of life

The movie Imitations of Life, was made for my nephew, it looks at the futures that movies have on offer. It’s a kind of essay, but instead of pen and paper, there are pictures and sounds. Well let’s see it, let’s bring in the evidence, and so the movie brings forward a number of clips. It’s a container, it’s a frame, for pictures. Like every movie of course. And it finds that these pictures, many filled with the kind of beauty that only money can buy, many of these expensive day dreams, are busy remapping a future that operates just like the past. Oh look, it’s the same lonely detectives, the same deadly women, in other words, the same kind of fear, but in brand new clothes. Mother, father, it’s you again. And again.

But just as these pictures can be lifted out of their original settings and reshuffled, just as the arrangement, the arrangement that is our personality, can change, it offers, or I would like to imagine it offers, a hope for something else. It offers a hope for my nephew, my boy. It offers a hope for his arrangements. His personality. And it offers this hope not up there, on the mountaintop, and it’s not way up in the sky where the angels of genetics flash their million dollar smiles. It offers its hope down here, not as Brecht would have it, not with the good old things, but the bad new ones. We are tired and scared and lonely, but from this aging body, filled with holes, there is still a hope, precious hope, that the arrangements are not fixed, that we can juggle the parts so that the future doesn’t need to repeat the past, so that we can see what it means when the multi-million dollar president is wearing blue jeans, so that we look right through the smoke and mirrors of the atomic bomb and every other state-sanctioned lie they tell us, in order to start the next war.

I would like to leave you with a Nashville valentine. It’s a short movie which runs just five minutes. It’s a movie about children, children who have grown up and who now look like adults. It’s set in a city, maybe a city like this one, where everyone is in good company, but feels themselves, if only for a moment, an instant, absolutely alone. And in that lonely moment there may arrive some insight, some special understanding which turns into an opening, a kind of clearing where each of us can leave behind the convenient fictions, the soft places where we’ve rounded off the truth, where we’ve left behind the small lies and are able to step back into the world and see it as it really is. Ready to say yes. Yes I can. Yes I must. Yes we must.

(Frist Museum talk, Nashville, February 14, 2009 and MacKenzie Art Gallery, Regina, Feb. 25, 2009)