Talk given at Gravity, Toronto, May 5, 2015

I’d like to say a few words today about this curious term that is used so often in rooms where Buddhism is practiced, the word is sangha. It’s not the father, the son and the holy ghost, Buddhism’s triple gem is known as the Buddha, the dharma, the sangha. Sangha is usually translated as “community.” Does community happen any time folks come together? Is community like a vibe, an atmosphere, a feeling tone? Can someone be part of your community if you don’t know their name, or don’t really know anything about them?

The forms of Buddhism that this group has been engaged in have often been very practical. These forms ask: what does that look like as a practice? So, what does sangha, what does community look like as practice? What is the practice of community?

History

A few historical words. The word sangha used to point to a very specific group. The community meant all those people – at first only monks – who were gathered around the Buddha and who travelled with him. This group expanded to include people who were not monks, and then after some discussions, women. This was in the fifth century before the common era. At this moment Indian society is very stratified, unfortunately, much like today. There are upper class people, and untouchable people. One’s parents were a kind of destiny. Everyone had a role, a part to play, an economic class they were condemned to. The Buddha offered a radical alternative, he wasn’t alone in this, there were others who had groups around them, but in the Buddha’s group, there were no priests who knew more than everyone else, no one had special understandings or knowledge, everyone shaved their heads and wore the same crappy kind of robes, and it didn’t matter what class you had started from. Here, in this group, in fact one of the defining features of this group, is that you were newly equal. It is a radical exercise, a radical embodiment of democracy. And while it is religious, it is not a religion. It doesn’t offer the big answers to the big questions (why do we exist?), there is no God, perhaps, some are arguing, there is no afterlife. There is only this. This moment.

Awake

The community, the sangha, are undertaking together a collective project. What is the nature of that project? I believe that it is a project of awakening. How does the chant go that we wind up every evening with?

“Life and death are of supreme importance.

Time passes swiftly and opportunity is lost.

Let us awaken. Awaken.

Do not squander your life.”

Can you hear in these lines the implication that squandering your life, that wasting your life, might have something to do with awakening? Opportunity is lost. This is what the line says. Opportunity is lost. Opportunity for what? Eating ice cream? Driving fast cars? Maybe. The chant says: Opportunity is lost, and then it seems to answer the question it poses: Let us awaken. What opportunity have we lost? The ability to awaken. We have an opportunity to awaken. And it’s not enough to say it once. I can hear an anxiety here. It’s as if we keep forgetting. Or that our conditions, the busyness of our lives for instance, forever leans us into the winds of forgetting. So the chant goes: Let us awaken. Awaken. It’s like setting two alarm clocks. It’s like having the word underlined, doubled down. Awaken. Awaken.

And then we hear: “Do not squander your life.” Doesn’t this imply: if you aren’t trying to wake up, you’re squandering your life.

So, we’re trying to look into, to peer into this mysterious word: sangha. The community. And when we look into it, we find this other quality there, this thing called awakening. There’s a hint that this gathering, this grouping here, is trying to support the project of awakening. Isn’t it? Let’s get back to this in a moment. But first: what is awakening? If you could only use one word to describe it, what would you say?

Me

The traditional viewpoint, supported moment by moment by our incessant, never ending monologue, the story we never seem to tire of telling ourselves, even when we’re asleep, is that I am the centre of the whole universe. Whatever happens in this room is happening first of all to me. Me me me me. It’s my meditation practice, it’s my sangha, it’s my aching back, it’s my long commute to get home, my empty stomach. Sometimes you hear people talking about the long winter we’ve been having as if it’s something that’s been designed just to happen to them. My winter. Why am I being punished by this winter?

It seems to me that the project of the dharma, the project of what we sometimes call in this room ‘the practice’ is taking this me-centered version that is our inheritance, and shifting it, so that we can experience the world in a very different way. So that we can feel what the world is like when it’s not feeding the me-place, the me point of view.

Joan

Here is Joan Halifax, legendary Zen queen, from a chat she had just a couple of months ago, on the question of sangha, of community. Joan: “Community is a really important part of the experience of spiritual development. It is said that the most difficult and challenging of the jewels (the three jewels: the Buddha, dharma, the sangha), the most difficult and challenging of the jewels is the third, the sangha, because ultimately it’s an antidote to ego. I was thinking about the teachings of St. Benedict in this regard, because the most valiant monk is not the solitary or even the beggar, but the one who chooses to live with others in community. Community is really important in the development of character, including the dissolution of one’s own ego. Living in a healthy community offers little escape from who we are. Ultimately community is about love – it’s about doing very simple things for each other, which could include cooking together or cleaning up or helping with the needs of others.

Sangha is also about sharing our resources with each other, including our minds, our insights and our time. (Are these the three key factors of sangha? Giving to someone else our minds, our insights and our time. The gift of time.) It’s how we in the community allow each other to develop. Both in Buddism and the Benedictine model, our spirituality in the community setting is not really about the local self, but about the extended self. And the extended self is about benefiting others. Just living with other people doesn’t necessarily make community. We have to share the same reservoir of values. We also have to have a common commitment.” (The Three Jewels: an interview with Roshi Joan Halifax by Sean Murphy https://www.upaya.org/2014/07/three-jewels-interview-roshi-joan-halifax-sean-murphy/)

Sitting

Let’s look at a local example, something we do here every week. We sit for half an hour, and we try not to move around when we’re sitting. Why? Moving, even if you’re itching your nose, or you’re trying to relieve your aching back, is a way of saying: I’m going to change this moment so that it’s more like what I want. By giving in to our reactive selves, our sometimes unconscious self, we put ourselves back on the throne. It looks like I’m just scratching my shoulder during sitting practice, but actually I’m putting a crown on my head I’m going to rule this moment. Of course, sometimes it’s necessary to move, I’m sure you’ve all heard terrible stories from people who go on retreats and ruin their knees or their backs. But we try to move in awareness, I’m going to move my leg, what does that feel like? What are the sensations involved?

By not moving when we’re sitting, or by keeping movement in awareness, we take ourselves out of the me-place. I don’t have to express my authority, I don’t need to impose my will on this moment, in fact, I don’t have to change a thing. What if everything were fine, just the way it is, right here and now? Would I still know who I am? What if those pains in my back and knees were just energies, and they’re not just flowing through this container, this frame, it’s flowing through other containers, in fact we’re all part of the same container, the same room.

When all the chitter chatter starts to get quiet, that big choir of voices that keeps pointing out how hungry you are, or how important you are, or how not important you are, the way those voices keep bending every experience so that it’s your experience, when those voices get quiet you can start feeling oh, so light, and all of a sudden there’s not so much distance between you and the pain in your knee, oh let’s go investigate that, how interesting. Instead of aversion, there is curiosity. And then you’re back here, and then you’re busy asking questions again. What’s that like?

Awake

There’s a few myths or stories that continue to cling to the idea of awakening. The first idea is that awakening happens only to special people under special circumstances. Wow, are you like, awake right now? I was very surprised to hear Zen maestro Bernie Glassman talk about awakening as if, actually, everyone has experienced awakening. It’s just that some people have very small awakenings. Very small. Oh I know that you’re in there somewhere, come out! And other people have very big awakenings.

Bernie Glassman: “The way we can see how deeply one has let go of attachments (as if holding onto things, holding onto our favourite neurotic loops, keeps us pinned down, keeps us isolated), (the more one lets go) and realizes the interconnectedness and oneness of life… is how much that person is serving others. If the person is only serving themselves then that’s what they see as the world. If they are interconnected with the whole world, and they see that as one thing, then they can’t help but picking a person up who falls. In the Christian world that’s seeing others as Christ, in the Buddhist world it’s seeing the oneness of life. That’s what I call spirituality.” (From Instructions to the Cook: A Zen Master’s Recipe for Living a Life That Matters, a film by Christof Wolf)

It’s interesting the example he uses. Picking up a person who falls. It’s as if people were falling all the time. Is that why you come here? Because you’re falling. Sometimes falling can feel so good. Oh, I’ve just fallen in love with you. But there’s also a falling without a ground, a falling that goes on and on and that’s usually experienced as terror. I wonder, when I hear this passage, if being able to recognize if someone is falling, if someone around you is falling. Does that have something to do with community? It’s just a question. I’m not talking about putting your superhero cape on and saving them. I’m just talking about bearing witness. I can see you. I can see your pain. I don’t need to do anything about it, I’m not going to pretend to fix you up, but I want you to know that you are visible to me, your smallness. When we’re hurt we get so small, we’re so small and fragile we can become invisible except for the people who can see people falling. They have dharma eyes, they have appropriate view. The first step on the eightfold path: appropriate view.

Here’s Bernie Glassman again: “What if my left hand is called Mary, and my right hand is called John? They are connected to Bob. They are parts of Bob. John suffers a terrible cut, so what does Mary do? Well, Mary (the left hand) might make a mistake, she never studied medicine, so she just watches while John (the right hand) bleeds to death. And the result? John dies, Mary dies, Bob dies. But what if Bob can feel that Mary and John are parts of him? Then if John suffers a terrible cut then Mary will do something. It might be the wrong something, but it will be something. And that’s all we can do. To act out of compassion.” (Bernie Glassman talk given at Hart House Theatre in Toronto, Sept. 9, 2011)

Isn’t that beautiful? Even if you’re doing the wrong thing, it’s still an act of compassion, an awakened act. It doesn’t mean that it’s going to last forever. It might not even make you feel good. But for at least a moment, you’re awake. Awakening is a verb, it’s something you do.

Room

Number two myth about awakening. I used to think it was a room you got to live in. Oh I’m sorry we can’t let you in here, only enlightened beings can sit on this furniture. I used to think being awakened was like until death do us part, you step into that room and you never leave. But the way Bernie talked about it made me realize that, like everything else, awakening comes and goes. Arising and passing away. Fundamental law of physics. Everything arises and everything passes away. Awakening is not a place like heaven or Paris or Hawaii, it’s a verb, it’s something you do, that you work at doing.

Happy

Now the third myth that continues to cling to the idea of waking up, is that being awake is a happiness machine, it makes you feel good. It’s the magic juice flowing through your veins night and day. Oh I can hardly wait until I’m awakened. But it’s interesting the example Bernie gives, of a bleeding hand. Even when the other hand helps, the wound is still there. And now the helping hand also feels its own vulnerability. Hey that shit could happen to me. I used to feel invulnerable but look at all that blood spilling out of John, that’s a bummer.

What I’ve found, in my experience, is that waking up is sometimes unwanted and difficult. Let me give you a small example.

My friend Mark was an animal rights activist. He would organize demos against companies that used animals for product testing, he made movies that showed what happened at slaughterhouses. I was very resistant, and it took a long time, and it’s still something that I slip in and out of, but I’ve started to wake up to the reality of animals, and animal suffering. It means: eating that hamburger would be like eating my best friend. Would you eat your best friend? Would you cut him up and fry him on a grill and eat him? Even if he came with special sauce? And when you start waking up to animals, which means waking up to the suffering of animals, you start looking at the city as an endless factory that condemns millions of animals to lives that are cruel from the moment of their birth to the moment of their death, living in their own shit, overcrowded, airless, never seeing the sky even once in their life, filled with antibiotics, penned in, abused, in a word tortured every day of their life. And you see how this whole city is made possible by the ruthless exploitation of this underclass, how we are made rich by making them poor. How much easier it was never to have any of this in mind, to be completely ignorant. Oh I’d like to have three bars of that good chocolate that was harvested by slave children in the Ivory Coast. and I’d like to eat those heads of lettuce that were grown by underpaid illegal Mexican migrant workers who are chronically mistreated in California, and I like to buy my clothes at Joe Fresh for super cheap because they pay their workers pennies per day and they have to work terrible hours in factories that are so crappy sometimes they collapse and all the workers die but that’s ok because my shirt only cost $5.

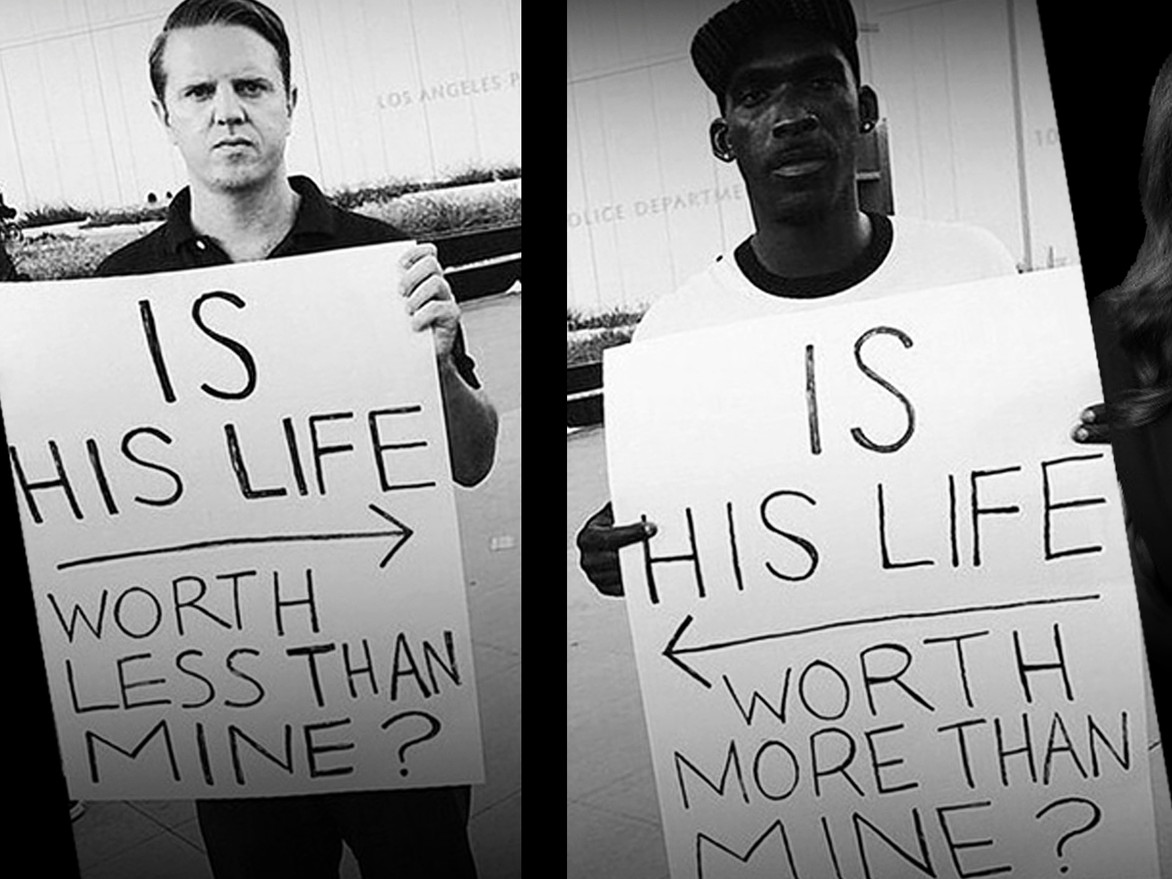

Michael Brown

Waking up can be a very difficult feeling. There’s been a lot of coverage lately about black men being killed by American police officers. And I think it’s pretty clear that the only reason it’s in the newspapers is because after Michael Brown was shot point blank by a cop and left to die on the street in Ferguson, Missouri, his friends and then his neighbours, and then people who had never met him, and then people who don’t even live in Ferguson felt: Michael Brown is me. I’m that guy lying face down on the street. And I can’t let that happen anymore. I think that’s waking up. That moment of identification, that moment of interdependence, is a moment of waking up. A whole community has begun to wake up. And is that a good feeling? Well, OK, there are some good feelings, the solidarity, meeting others who are bent to a common purpose, sure, that can feel good. But there is so much pain, so much anger, and you feel the injustice ringing in your pelvic floor, and that’s so hard.

Did you read the recent article by Desmond Cole, handsome middle class guy, sharp dresser, writer, super smart. Stopped by the police in Toronto fifty times. He’s never been arrested, never charged with anything, never seen a courtroom. Fifty times. Oh did I forget to mention? Desmond is black. Desmond Cole doesn’t have to wake up to the fundamental injustice of the police and legal system, the racism that confronts him over and over again.

And once you’ve woken up you try to get other people to wake up, you can see the place you used to be in, but often because they’re white and you’re black, or you’re a woman and they’re a man, or you’ve changed your gender and they’ve never given gender a thought in their whole life, so it’s really hard for them to wake up.

The people on the streets of Ferguson, those people who put their bodies on the front line, have made the papers report what they didn’t report last year, or the year before, or the year before, that black people are being targeted, and harassed and killed on the streets of this continent in a systematic way because they are black.

Waking up to white privilege, or the privilege of being cis-gendered, or the privilege of not having to be killed when you’re two or three because your meat will be extra tender and tasty then, those are not good feelings.

Question

We started with this question: what is community? We posed this question inside a Buddhist frame. What is a Buddhist community, if it’s not the folks who were living and travelling with the Buddha?

And when we looked inside, when we opened the lid we found this word: awakening. Let us awaken. Awakening, please correct me if I’m wrong, and I’m eager to hear your thoughts about this, but I think awakening is a central piece to the project of Buddhism. And that project feels so hard. It’s fraught, it can bring us so many difficult feelings as we step into the lives of our sons and daughters, as we try to support our partners, or bear up to difficult work situations.

So my theory is that we need community to help support us in this difficult project. Does that sound crazy to you? Is awakening only for special people, only for someone else, later, at another time, the ones with the shaved heads and the robes?

And it makes me wonder what that looks like in this room. I mean: what might that look like for you? Another way of asking this question is: how can we help you? How can we support your project of awakening?

What does your project of awakening look like? Is it possible to say that, at all, even in a small way? I wonder if we could form small groups, perhaps groups of three, and talk about our experiences of waking up. And how community supported that project, or didn’t support that project?