Contact

A few weeks ago Grant gave a series of talks about the five kleshas, the five poisons. They were very practical talks I thought, that offered a description of what happens when we experience something. Whether it’s the smell of bread being baked, or the sight of a friend’s face, there is contact, there is a meeting, an intersection, a contact point between sense object – your friend’s face is a sense object – and this sense object meets a sense organ. Eye, ear, tongue. The contact between a sense organ and a sense object produces a sensation somewhere in the body. In fact, when you take the contact point as your practice, if you bring your attention to the sensations in the body that are happening right now, in this room, we might begin to notice that there are sensations occurring across the entire surface of the body, in every part of the body.

What are the sensations arising in the frame of experience right now? (Ask the group)

Gross Sensations

Usually I don’t notice my body until I have what Mr. Goenka likes to call “gross sensations”, big sensations, loud sensations. I put my hand on the oven, oh, that’s so HOT! And all of a sudden I have a hand again. I fall down and bruise my leg, Oh my leg is in such pain. I don’t even notice I have a leg until it’s in pain. Does this ever happen to you? Sometimes I think that the pain I experience is simply the pain of being reminded that I have a body. For six months I couldn’t lift my left arm. It was just too painful. And this pain was a reminder: you have a left arm, a left shoulder. And more than that: you have to look after your left shoulder, you have to give it kindness and attention. You have to ask: what does this shoulder need? Shoulder: what can I do for you.

The practice of working at the contact point between sense organ and sense object, means bringing attention not only to the big sensations, because we don’t really need a practice for that. Anyone wandering through Queen Street tonight can feel these big sensations. But the invitation is to bring the small sensations, the quiet sensations, the sensations who sit at the back of the class and never say a word, let’s bring those sensations into awareness.

The Buddha asked us: “to observe whether the body and mind are distracted or steady, angry or peaceful, excited or worried, contracted or released, bound or free.” The foundations of mindfulness lie in the frame of this body, the sensations of this body.

Experiment

Could we try an experiment, a demonstration? I’d like to invite you to bring your hands together until they’re almost touching. And if you want, if you can, you could bring your breath into your hands. We can move the frame of attention through our body by using the breath, I would encourage you to bring your breath into your hands, fill them swell slightly with the inhale, feel them deflate slightly with the exhale, but if you can’t feel that, don’t worry about it, it’s not so important. Just try to live inside the surfaces of your two palms that are almost touching. Can you feel the energy flowing from one hand to another?

What are your sensations? Like any good scientist we’d like to gather up our data. What are the sensations you can feel in your hands?

You can touch someone, you can be touched by someone, without actually touching them. We are touching the world all the time, and we are being touched all the time. There are sensations running across our body all the time, even when we’re sleeping. And when the sensations arrive there is no morality. There is no judge. The sensation is not good or bad, neither the best nor the worst. This is a whole practice, simply to stay with a sensation before it is submitted to the court of opinion, before you submit your sensations to the judge who decides… what does the judge decide?

The judge says: I like it, I don’t like it, I’m neutral. All sensations, all experiences – the judge makes the same three calls over and over again – from our youth to our old age. I like it, I don’t like it, I’m neutral.

Pema

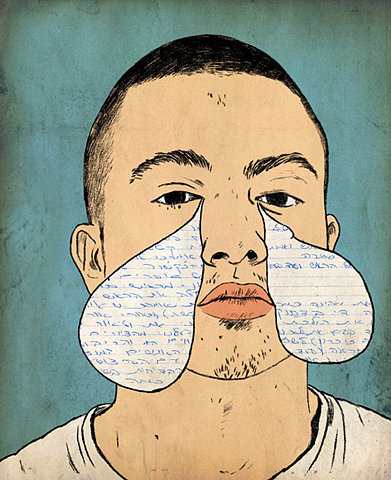

I wanted to say a few words about I like it. Not just I like it but I LIKE IT. I’m going to be guided in this talk by the forever wise Pema Chodron. She was born in New York City, married twice, and after her second divorce (what am I doing wrong?) she plunged into Buddhism. She wrote her first book when she was 55 years old. When I read some dharma writers I hear them saying: Meditation is so wonderful, so perfect, it lets me ride through the clouds, I welcome anger, depression and heart aches because they make my practice stronger. But Pema writes from a broken place, so when I read her I can feel my own brokenness being welcomed. Usually I like to hide this broken self. How are you? Good. Great. I put my face mask on, the face mask that says: I’m OK, I’m coping, I’m alright, even and especially when I feel terrified or small. Being OK is my first line of defense. What would this face be like if it wasn’t my first line of defense? Pema’s words invite all of my unwanted, undernourished selves to come into the room. When I read her words it’s like I can feel someone patting the couch and saying: here, come sit down beside me.

This is Pema from an essay she wrote a dozen years ago called How We Get Hooked (2003).

“You’re trying to make a point with a coworker or your partner. At one moment her face is open and she’s listening, and at the next, her eyes cloud over or her jaw tenses. What is it that you’re seeing?” (Another way of asking this is: what are the sensations in your body?)

Now she’s going to answer her question: “Someone criticizes you. They criticize your work or your appearance or your child. At moments like that, what is it you feel? It has a familiar taste in your mouth, it has a familiar smell. Once you begin to notice it, you feel like this experience has been happening forever.”

Samskara

The experience, the sensations that occur when you’re being judged, the sensations of being criticized, it feels like this moment is not just happening now, this moment is hooked, it’s attached to all those other moments when you were criticized. They’re all hooked together in a big chain. Those past moments created certain pathways for sensations: certain kinds of tastes, certain kinds of smells. The Buddhists call these superhighways that run across our body of sensations: samskaras. These samskaras are deep grooves running across our bodies, into our noses, across our tongues, into our ears. There are sensations happening in every part of our body, but it’s very difficult to bring all these sensations into awareness at the same time. Our samskaras are like a highlighter pen: this is important, and this one, and this is important. But they’re also like a groove in a record, they help to create certain kinds of sensations inside the frame of this body. The frame that we practice in. It’s as if we’re running a hundred yard dash, but instead of lining up straight at the blocks, we line up like this. This is our samskaras at work, this is what feels straight to us. And the practice is not about scolding ourselves, or even getting us to be straight in the blocks, but only to notice what direction we’re going in.

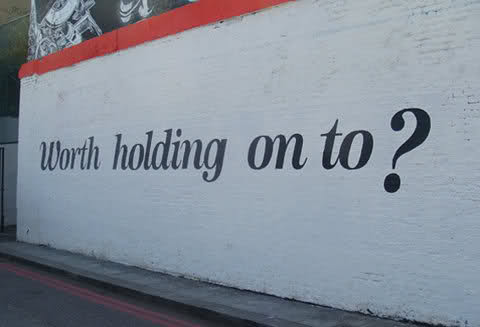

Pema: “The Tibetan word for this is shenpa. It is usually translated as ‘attachment,’ but a more descriptive translation might be ‘hooked.’ When shenpa hooks us, we’re likely to get stuck. We could call it ‘that sticky feeling.’

So the sensations, the physical sensations that arise when we’re feeling criticized, or when we feel ashamed, or jealous, or angry, often they don’t arise and pass away and make room for new sensations – they loop. Have you noticed that? The sensations replay over and over again. It’s strange because when I hear the word “attachment” I think of happy, easy beautiful faces, but mostly I’m attached to not-so-nice things. Is it strange to admit that I’m hooked, I’m addicted even, to not-so-nice things. To being criticized, to the act of self-criticism, or to punishing myself. I reach for it the way others reach for cigarettes or chocolate.

Pema: “When we’re hooked, we’re likely to get stuck. We could call shenpa ‘that sticky feeling.’ It’s an everyday experience.”

Isn’t that beautiful? With this one line Pema deflates the whole cycle. Of course it feels bad – and you’re addicted to feeling bad, but you know what? It’s an everyday experience. It’s ordinary, everyone goes through this. And I hear in this line a relationship to practice. If getting hooked is an everyday experience then perhaps that’s where practice might be most helpful, perhaps that’s where the healing can happen – right at the contact point of sense organ and sense object.

Pema: “It’s an everyday experience. Even a spot on your new sweater can take you there. At the subtlest level, we feel a tightening, a tensing, a sense of closing down. Then we feel a sense of withdrawing, not wanting to be where we are. That’s the hooked quality. That tight feeling has the power to hook us into self-denigration, blame, anger, jealousy and other emotions which lead to words and actions that end up poisoning us.”

Sensation

Can you hear how the contact point – someone’s look, or a word of judgment – creates a physical sensation that Pema describes as “tightening,” and then “a sense of closing down,” withdrawal, possibly then anger-in (if self-blame is your schtick) or the other favourite anger-out: why are you looking at me like that? What she’s doing with her practice is noting with curiosity: what is happening in the frame of this body, this frame of practice, when I get hooked? She begins with sensation. She begins her noting at the contact point that produces sensation. She notes tightening, she notes closing down, withdrawal, and then there are emotional states – anger or blame. There is a chain of events, one event follows the next, and this happens over and over again. She is creating a map of her own reactions, her own samskaras. This is what I do when I feel scared. It takes her out of the level of ideas and abstractions and it brings her back into the body, into the place that is tightening.

Here is Pema again, describing the contact point. “Someone looks at us in a certain way, or we hear a certain song, we smell a certain smell (there is contact between sense organ (the nose) and sense object (the smell), we walk into a certain room and boom. When we were practicing recognizing getting hooked at Gampo Abbey, we discovered that some of us could feel it even when a particular person simply sat down next to us at the dining table. Being hooked thrives on the underlying insecurity of living in a world that is always changing.”

Fear

You know the moment in this room when all the official, scheduled time ends, when the unofficial time starts? Sometimes I can feel my chest waving like a piece of paper, and then this tightening of my diaphragm, in begins here in the midchest and then it rises, and these tightening sensations are what I name as “fear.” Because we’re in the unofficial time, anything could happen. What if I can’t come up with something to say? What if I show my broken face, instead of my mask? This is part of what Pema calls “the underlying insecurity of living in a world that is always changing.” There’s a way that our schedule, the half hour sit, the bowing, the way we come into the room – they are forms of attention, they are devices or frames that can help us bring attention to this moment, and that’s great, wonderful, but they are also a way of dealing with my fear, my social anxieties. I do this in my life over and over, for instance, when the official time stops and the unofficial time begins I’ll try to look for a familiar face, a face I already know, and I grab onto this face. Have you ever done this? I grab onto this face so that I don’t have to deal with “the underlying insecurity of a changing world.” It’s a way of hiding, and of minimizing risk.

Pema: “Getting hooked thrives on the underlying insecurity of living in a world that is always changing. We experience this insecurity as a background of slight unease or restlessness. We all want some kind of relief from that unease, so we turn to what we enjoy—food, alcohol, drugs, sex, work or shopping. In moderation what we enjoy might be very delightful. We can appreciate its taste and its presence in our life. But when we empower it with the idea that it will bring us comfort, that it will remove our unease, we get hooked.”

Addiction

So we could call getting hooked “the urge” – the urge to check Facebook, the urge to check our emails, to binge TV shows, to indulge our addiction whatever it is. And everyone is an addict. That was the startling message from Gabor Maté, the doctor who works in Vancouver’s lower east side, the poorest postal code in the country. I thought I was reading his book because he was going to tell me about how life was for the people who were struggling with crack and alcohol and heroin, and then I realized I was reading a book about myself. The good doctor is very clear on this point: some addictions are just more visible, more socially acceptable, than others, but everyone in this culture is an addict. The question is: how are you dealing with it? Or how is it dealing with you?

The momentum behind this urge, the urge to feed our addiction, the momentum behind this urge is the way Pema translates “samskara” – the physical, emotional, cultural groove – she calls it momentum.

“The momentum is so strong that we never pull out of the habitual pattern of turning to poison for comfort. It doesn’t necessarily have to involve a substance; it can be saying mean things, or approaching everything with a critical mind. That’s a major hook. Something triggers an old pattern we’d rather not feel, and we tighten up and hook into criticizing or complaining. It gives us a puffed-up satisfaction and a feeling of control that provides short-term relief from uneasiness.

Those of us with strong addictions know that working with habitual patterns begins with the willingness to fully acknowledge our urge, and then the willingness not to act on it. This business of not acting out is called refraining. Traditionally it’s called renunciation. What we renounce or refrain from isn’t food, sex, work or relationships per se. We renounce and refrain from the hook. When we talk about refraining from the hook, we’re not talking about trying to cast it out; we’re talking about trying to see the hook clearly and experiencing it. If we can see the hook just as we’re starting to close down, when we feel the tightening, there’s the possibility of catching the urge to do the habitual thing, and not doing it.

Buddhists are talking about the hook when they say, ‘Don’t get caught in the content: observe the underlying quality—the clinging, the desire, the attachment.’ Sitting meditation teaches us how to see that tangent before we go off on it. It basically comes down to the instruction, ‘label it thinking.’ To train in this on the cushion, where it’s relatively easy and pleasant to do, is how we can prepare ourselves to stay when we get all worked up.

Then we can train in seeing the hook wherever we are. Say something to another person and maybe you’ll feel that tensing. Rather than get caught in a story line about how right you are or how wrong you are, take it as an opportunity to be present with the hooked quality. Use it as an opportunity to stay with the tightness without acting upon it. Let that training be your base.

…unless we equate refraining with loving-kindness and friendliness towards ourselves, refraining feels like putting on a straitjacket. We struggle against it. The Tibetan word for renunciation is shenlok, which means turning the hook upside-down, shaking it up. When we feel the tightening, somehow we have to know how to open up the space without getting hooked into our habitual pattern.”

Tara Brack: “Marilyn had spent many hours sitting at the bedside of her dying mother – reading to her, meditating next to her late at night, holding her hand, and telling her over and over that she loved her. Most of the time Marilyn’s mother remained unconscious, her breath labored and erratic. One morning before dawn, she suddenly opened her eyes and looked clearly and intently at her daughter. ‘You know,’ she whispered softly, ‘all my life I thought there was something wrong with me.’ Shaking her head slightly, as if to say, ‘What a waste,’ she closed her eyes and drifted back into a coma. Several hours later she passed away.”

We’re such fragile creatures, so helpless, like children. We’ve been hard wired to let all the joys and happiness flow through us, and to grip hard onto every bit of pain and anguish and heartbreak we’ve ever experienced. We’re very vigilant, so often on the look out, for experiences that we can add to our personal treasure trove of heartbreak, hahaha I’ve got it all, I’ve got all the pain in the world. Pema’s invitation is to notice the contact point where we get hooked, the contact point where something throws us off balance, something threatens us, a word, a look, someone cuts you off on your bike, cuts in front of you in the line up, contradicts a cherished opinion, doesn’t notice something you’ve put effort into, and you get hooked. And then the old patterns come back, the old voices, the old sensations. The invitation is not to rise above it all, the invitation is not to destroy the old habits, the invitation is to investigate what is actually happening, to look into the sensations of the body, to create a map for yourself of your own chains, your own physical patterns of sensation, and using that map you might begin to loosen the hold of the old grooves, you might begin to develop what Adam Phillips says, is not a fate, but a repertoire, a number of options, in other words, you might become an artist of your own life, and deal with these difficult moments with some new kind of creativity.