“The prolific Canadian artist Mike Hoolboom takes his inspiration directly from the heart. His pictures begin with the innermost secrets, as a whisper, a caress. While the approach is experimental, the sincerity of this humanist quest raises the pulse of even the most indifferent moviegoers.” Olivier Thibodeau, Panorama Cinema, March 2015

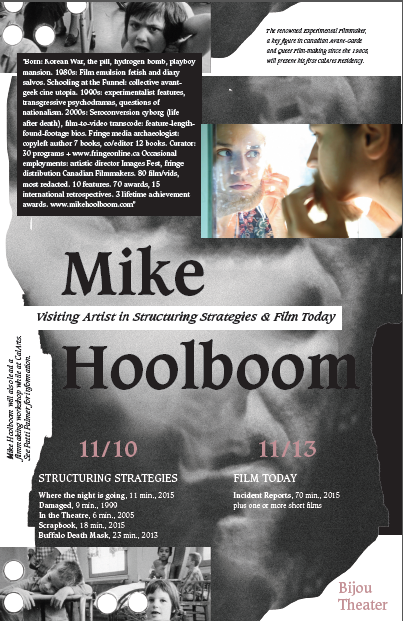

The renowned Canadian personal experimental filmmaker will be at CalArts for his first residency, Nov. 10-13, 2015.

Mike Hoolboom has been a key figure in Canadian avant-garde filmmaking since the 1980s. A passionate supporter of independent filmmaking, Mike has produced a large body of varied work, curated numerous programs and series for international venues, and has written for and edited journals devoted to experimental cinema.

Hoolboom’s powerful, personally expressive films include self-portraits and portraits of friends and artists, and he has won prizes at major film festivals in North America and Europe.

Structuring Strategies class with Steve Anker

Program One

Where the Night is Going 11 minutes 2015

Notes on belonging, the costs of arrival, of being admitted to the party. A moment of encounter is unpacked while the dreamy spectacle onstage offers model citizens new roles to play. Guy Debord posts a new documentary frame. Further thoughts on the slave mechanism.

Damaged 9 minutes 2002

Damaged is a ten minute portrait of an indecisive man related in eighteen decisive moments. A series of still pictures offer models of childhood, sexuality and adulthood, while a voice-over makes the drive run smooth.

In the Theatre 6 minutes 2006

“One of the tribute videos for the late artist Colin Campbell, it continues Hoolboom’s expert reworking of pictures from the whole history of cinema. A river of stolen images from the most ancient, rusted celluloid, to the glossiest Hollywood scenes paints a picture of anxiety. Meanwhile, text names the movie theatre as ‘the place where we watch death at work.’ When a young Colin Campbell finally shows up in an old video clip and speaks, it’s nothing short of spectacular.” Cameron Bailey, NOW Magazine

Mexico (with Steve Sanguedolce) 35 minutes 1992

“Mexico ruthlessly unmasks and dissects the assumptions and half-truths we tell ourselves about development and progress. Not so much a film as a series of live-action postcards, the images are sustained by an incisive voice-over. The tour ranges from an archeological museum to a car factory (’a factory which produces only smoke’) to a hideously graphic bullfight, linking cultural colonialism to free trade. ‘Everything you touch turns into Toronto,’ Hoolboom says, and this vacation jaunt ends with the disquieting transformation of the Mexico City streets into the 401.” (Josh Ramisch, Variety)

Buffalo Death Mask 23 minutes 2013

A conversation with Canadian artist Stephen Andrews returns us to a pre-cocktail moment, when being HIV+ afforded us the consolation of certainty.”

Film Today class with Eduardo Thomas

Program Two

Incident Reports 70 minutes 2016

After a bike accident, the amnesiac undertakes audio-visual therapy by producing a suite of one minute shots. The voice-over weighs in on gender, animals and the end of literary culture. A love story essay featuring Elvis, wrestlers, boy ballet, naked cyclists and the heavenly voices of Choir Choir Choir.

Frida 25 minutes 2015

One chapter of a six-part work-in-progress about the lives (and deaths) of artists, Frida looks at the artist as brand, as reproduction vehicle, as query and queering authorial texts.

Safety Film Collection 25 minutes 2014

A found footage collection of 26 AIDS adverts. Freud uncovered the mysterious connection between language and bodies at the same moment that moving pictures provided new behavior modellings. How do pictures change desire, or the behaviours of desire? This question carried extra weight after the outbreak of the AIDS epidemic, as movie makers struggled to find combinations of pictures that might help create the conditions for safer sex.

Who Are We? (Introduction to Program One)

One of the happy confusions of this classroom is that it’s so much like the cinema, don’t you find? Or at least, it’s so much like the cinema as it used to be, because the invention of the movies, the question of projection, of the way we project, and what we’re going to project, is not separate from the question of how we come together to make this… this coming together, this collection of bodies. The cinema — it has something to do with bodies, doesn’t it? It has something to do with your body, and the way your body changes when it comes into contact, when it comes at least into proximity, when it’s gathered up, when it surrenders, is that too large a word to use, when your body releases itself into this collection of bodies. So the question I’d like to ask you, the question I’d like to return to in different forms today, is: who am I? when I’m here. When I’m here with you and you and you and you. Who am I is another way of asking: who are we?

We like to pretend we’re one thing, one person, one body, you know, like God. But actually when you’re talking to your grandmother you change, you’re a different person, you speak differently than when you talk to your lover, your best friend, your film professor. We don’t live on a planet all by ourselves, the person we are is always in a relationship, and those relationships are part of who we are. I realize this can be a difficult thing to imagine in this country, because every person is entirely unique, no one like you has ever existed, and this country really likes to emphasize that part, but it’s also true that we’re parts of each other. It’s what Thich Naht Hahn, the Vietnamese monk, he calls it inter-being. We’re parts of each other.

The cinema is like the Vietnamese monk, it emphasizes the way we live in each other. The cinema did not begin privately. It was not an individual experience, it required, it demanded, that there should be a group, sometimes larger or smaller, and these groups would come together in what we like to call public space. Who am I when I’m in public space, when I am public space? The history of our cinemas, is also, at least in part, the history of the way we come together. Is it different than coming together in a classroom? When I feel myself inside this frame with you today the two feel very close, the cinema and the classroom.

The old cinema, the analog cinema, was related to mass production. We were also mass production. We were the mass, we were the mass that was being produced. And cinema was the art of mass production. We used to live in the countryside, in small villages, and now most of us live in cities. The cinema audience is a picture of this shift, this centrifugal force.

I was speaking with my friend Jean recently, and like all my friends he’s growing terrifying old in a great rush, as if we were in a hurry to leave this life. He said to me: “When I was younger I watched television on Sundays. Afterwards I usually felt depressed and lonely. I was looking but had this feeling of not seeing anything. I had shared nothing.”

It’s interesting this question of sharing. It’s as if when we come together we can’t help sharing. That we’re communicating to each other, even if we’re not using words. You can feel your neighbour’s attention, or their restlessness. Will this class never end? You know how when you meet someone sometimes you think: I like this guy! I like this person. You don’t know a thing about them, but your liver is happy, your kidneys are smiling. And then there are other people and you’ve never seen before but you think: I don’t like this person. That’s a bad person, this person doesn’t make me feel good. Each of us gives off a certain kind of feeling tone, what we respond to from a person isn’t what someone is saying, that’s just a lot of intellectual cover stories. What we’re responding to is the feeling tone. And they, on the other side, they’re responding to my feeling tone. Right? It goes both ways. In a room like this one, every single person is contributing to the feeling tone of this room. Could you feel the way the room changed, as we entered it, the whole vibe of the room completely changed. If one person left, the room would be different. Because you are the classroom. The classroom isn’t out there, the cinema isn’t out there. You are the cinema. You are part of this collective feeling tone, but also: you’re also separate, you have your own feeling tone.

Here’s Jean again: “Earlier I often went to the cinema by myself, and left screenings with a delicious loneliness which related to the world. Sometimes I was excited enough to talk about the film to someone I didn’t know. Loneliness in front of TV is violent and painful, while loneliness in cinema is a very subtle and fragile pleasure.”

I think Jean is telling me that there is a special kind of loneliness, a loneliness I can only feel when I’m here with you. Does it have a taste? Or a sound? What part of the body does this loneliness reside in? What are you doing with your loneliness? For me I think my loneliness keeps a certain kind of hope alive. The hope that I won’t be stuck inside the old ways perhaps, the old patterns, the old questions and the old answers as Sam Beckett liked to say.

I wanted to show you a movie, it’s very short and very difficult and it’s not finished. It relates to this question of how do we come together, and who are we when we do so. I was invited to make pictures of an event, and everyone was friendly and kind, but I felt a thousand miles away. Do you ever feel like that? When you’re talking to a friend, or a lover, at one moment you’re so close and then the next second, hey where did you go, where are you? They’re still standing in front of you, but they’re a thousand miles away. This movie was shot with a special lens and it’s the “you’re a thousand miles away” lens. When I got these pictures back, I felt the terrible distance between me and my loneliness, and these events, and I wanted to build a bridge so that there would be communication between these two places, these two solitudes. In order to do that I started a conversation between two people – the first was the genius Canadian poet Anne Carson and the second was Guy Debord. Anne Carson wrote about 19th century romanticism, the Bronte sisters, as if it was her own life. She would sit right where you’re sitting today, and her genius and her tragedy, is that the great works of literature, the great movies, she read them as if they were her life. And she wrote from that place, it’s absolutely singular, absolutely powerful. She was determined in other words not to leave her loneliness out of her writing. Guy Debord was the hard drinking Frenchman who took other people’s words and scratched out a line here, and inserted his own words instead, as if he do philosophy like a graffiti tagger. That was his way of taking history personally. He coined this phrase that I’m still mulling over. He said that a documentary is a picture that moves. This movie is a celebration of that question, or another way of asking that question. Who am I when I come to this place? And how can I create “a picture that moves” out of my loneliness?

We’re going to watch one, two, three movies, and then the lights will come back on. Who will we turn into then?