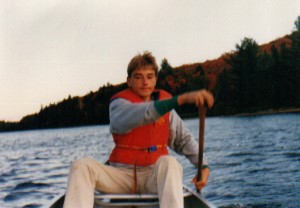

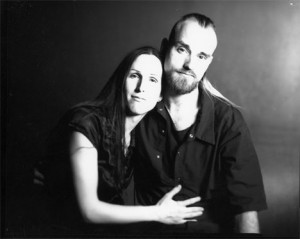

In April 2007 I was pulled aside by my friend Aleesa who had news she wanted to share. Of course we were in a movie theatre, where all the decisive moments of my life occur. We watched another important and badly made movie about jailed Palestinians, and when the crowds released themselves into the street, when our shadowy lives could begin again, she told me that our friend Mark had died. “Are you sure, are you absolutely sure, did you see him?” I had to ask over and over. There are some I can imagine dying, and those who seem already dead, but Mark was not even 36, a big smiling gifted optimist who moved like a dancer. We had worked together for the past half dozen years. We edited a portrait of my friend Tom together, and then the suite of biographies that would become Public Lighting, and then a small eulogy for Colin Campbell, and then a larger mosaic instrument which turned around Colin which was named Fascination. It happened unexpectedly, without a plan or a map, but as this new century unfolded, each year found us working on another biography. And now that he is dead, what else can I do but attempt to make a movie about him?

I miss him so much. And making this movie doesn’t make me miss him less, on the contrary, it brings him to life and kills him over and over again. At least it is a way to say some of the things he couldn’t say, some of the many things we never managed to say to each other, in our too short time together.

Making this movie means subjecting him to a cruel framing. Most often filmic biographies reduce the noise and confusions of our lives into tidy soundbytes, often into a single catastrophe, generally experienced early in life, which is repeated (with variations) and manages to explain everything. Every event, every gesture, no matter how small, can be gathered up and laid into lines which lead back to this event. This seems the reason for most biographies. Tell us the what and why, lay it all out for us, open these subjects up like a surgeon. Deliver us to the primal scene over and again.

At Mark’s funeral ceremony many asked why? Why did he take his own life? Some imagined others in the room knew exactly why he had died, and were refusing to tell. They longed for the consolation of a story, the way some warm themselves with heavenly afterthoughts or a final summerland after death. Mark’s extreme action required, above all, the balm of storytelling, there had to be some way to ease the pain and guilt of we the survivors. But Mark and I had worked these past years without stories, or with accumulations and groupings of stories. Perhaps Denzel Washington or Arnold Schwarznegger have acted out enough stories to become one. But for most of us, our lives do not inhabit the three act structure required by Syd Field and other script messiahs. We are left instead with fragments, a failing memory, a distant afterglow of kindnesses never fully received until it is too late. When I got on the plane to come to Europe the newspaper headlines screamed, “We will never forget,” but the truth is, we are already forgetting (our computer prostheses are teaching us well). In the face of the digital abyss we can hold up the memory of our friends for a moment, that’s all, before our time comes, to scratch out a mark, to leave some impression of a passing, and to scratch it as well as we can.

Let them call it biography. We are only trying to say good-bye.