We Were A Bunch of Friends: an interview with Frieder Hochheim

(January 2016)

Mike: You became part of a film screening group who were running open screenings in a four-storey downtown warehouse building owned by CEAC (Centre for Experimental Art and Communication) on 15 Duncan Street.

Frieder: I was into Dada and anti-art, so when I heard about this new group I thought: this is right up my alley. I was working part-time as a booker/shipper at the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre. Ross McLaren was also working there and he said “You’ve got to come down and check this out, there’s cool stuff happening.” That’s how I found out about the screenings happening in the CEAC basement.

Initially it was so much fun, this group of young filmmakers and artists getting together in a punk club in the basement of a building that housed the Liberal Party of Ontario headquarters. You had to get a kick out of that. We were not very subversive, but in those days people considered anything outside the norm subversive.

We were all dedicated to expressing ourselves through the moving image. I was a film student at Ryerson and there were a number of other film students there who had an appreciation for film history. We were experimenting a lot with film, exploring this art form, this cinematic language. What is cinema? It was a great opportunity to get together and toss around ideas. It was very reminiscent of what so many other art forms have gone through. It was like Dada’s Cabaret Voltaire where they would all get together to recite poetry and perform anxiety plays and feed off each other’s creativity.

The screening group was a huge stimulus for creative expression. When I got to see someone else embarking on a visual journey it would prompt images in my own head.

We were mostly students, though some people had jobs. Most of the students came from the Ontario College of Art. There weren’t a lot of other people from Ryerson, though John Porter went to school there for a long time. I think he attended the school for seven years.

Mike: Was that unusual?

Frieder: At that time people were doing unusual things, so if it took seven years to hang out at Ryerson, that’s what you did. Tuition wasn’t expensive. John was a very interesting filmmaker, he was exploring the boundaries of filmmaking, that’s what it’s all about.

Mike: John described meeting you on the street by accident, and you told him about a new theatre that was running open screenings. He said you called it “our theatre.” Did the theatre belong to everyone who came there, did you help build it and run shows?

Frieder: The theatre was a collaborative effort. We were a group of artists who had a passion for cinema expression, willing to try anything. It was our theatre. We would bring our work, and our work-in-progress. It was all about open screenings. Though we sometimes did other things there. At the time we couldn’t see any of John Waters’ films so we brought in Desperate Living (1977). One of the Funnel guys drove down to Buffalo, rented it and brought it back. It was very underground, the authorities were not to know about this because everything had to be passed by the Censor Board which is so absurd. They must have been exceedingly puritanical. There was no internet then so how did we get the word out? We would poster. We postered the art school and invited people to show up at 7:30 down in the basement.

I met Adam Swica there and later brought him into the film business. We were both students, and very much in sync. He became a very close friend. We started a small lighting company together with one other fellow, Bob Gallant, who within a year or two of our partnering up died tragically in a motorcycle accident. By that time our careers were evolving. The film industry was just beginning to embrace tax incentives. I started off as a lighting tech, best boy, then became a gaffer,. When the tax credits were pulled I had an opportunity to go to California with my wife. She had an offer to work down there and she was American, so we took off and I’ve been down here ever since.

Mike: Did you help create the theatre in the CEAC basement?

Frieder: There wasn’t that much work required, other than making the walls black. I don’t recall doing a lot of work on that one. There were a few of us when the walls were getting painted. It had to be black. It was also a punk club called Crash ‘n’ Burn. We showed our films on Thursday nights, and they were there Friday and Saturday nights.

Mike: Was the screening group called the Funnel?

Frieder: It wasn’t called the Funnel until later, Ross came up with the name. What do you want to call this thing? I don’t know, the Funnel? It cracked me up because: what is Dada? If you ask any Dadaist what is Dada they would tell you: I don’t know, it’s just what we called it. It meant nothing in particular.

Ross McLaren was the driving force behind the screenings. He had all the contacts with CEAC. He was the guy who pulled it all together. Hats off to his energy, he was very passionate. Ross and I always had mutual respect for each other’s work. He was the conductor, the ring master, he’d be the one to suggest let’s do this or that.

I remember Amerigo Marras, the head of CEAC. He was an interesting looking character whose hair looked like it was painted on his head. He was a character. But the CEAC guys weren’t around much, they provided the space and we operated on our own. They were busy doing their thing.

Jim Murphy was the heavy set guy who worked at the CFMDC. He helped out with the Funnel, and was very much involved. He wasn’t a filmmaker but he was someone who supported the group and was very interested in the work that was being generated there. He contributed emotionally to the well being of the organization. He also advised us about arts council grants and things like that. An avid film buff.

During the summertime I would work at the CBC in Winnipeg and ask all the camera guys to give me their short ends so I had a good supply of current film stocks. I remember the new colour negative stock 7247, 100 ASA. It was revolutionary. I would put that in my Bolex and load it, running off the first couple of feet to make sure I didn’t have any exposed footage. I did that in the closet of my apartment, aiming the lens nowhere in particular. When I got back the footage I saw that my roll off footage showed the crack of the door, it looked fabulous. I thought holy shit, this stuff is sensitive.

Mike: You worked in 16mm but a lot of others were working on super 8 – did that set you apart?

Frieder: No, the whole idea was that you work in whatever medium you had access to. We were very fortunate to be at Ryerson with its phenomenal facilities. I would strip the emulsion off and do the old Norman McLaren routine where you paint on the frames. 16mm was a lot easier to draw on than 8mm. All the early stuff I did as a kid was in 8mm, but once I got to Ryerson it was all 16mm.

Mike: In May-June 1978, after the Toronto Sun accused CEAC of supporting Italy’s Red Brigades the arts councils wanted to cancel their funding. CEAC asked the screening group for a letter of support, and there was a meeting called to discuss it. Do you remember that meeting?

Frieder: A lot of shit hit the fan with CEAC. I think that meeting might have been the catalyst for us to pull out because we weren’t about to give up what we were doing. We had to find another place, and were fortunate to find the one on King Street.

Mike: Did you help build the theatre at the Funnel in the summer of 1978?

Frieder: There was a whole bunch of us, whenever I had the time my efforts would go into it. We were very fortunate, there was a theatre closing down and they were going to be throwing out all their seating and we managed to scavenge about a hundred of their seats. We built a tiered floor with a projection booth, having a booth was phenomenal. We had 16mm, 8mm, even video playback for video artists.

Mike: Did building the theatre help build group identity?

Frieder: Oh very much so. It was everyone’s theatre. Everyone had a vested interest in making the theatre a success. At one point I was working part time at Northern Film Labs and they were getting rid of one of their old processors and I talked them into donating it to the Funnel. We were going to get that up and running so that we could process our own 16mm. But by the time we got that organized, I was working in the industry a lot more. Once you start working in the industry, with its 14-16 hour days, it monopolizes your life. Any free time you have you need to get your laundry done. That pulled me away from being able to develop my art. I still have a couple of unfinished films I recently dug up, I’m thinking of digitizing them and completing them in digital format.

Mike: After the first year of screenings at the new King Street location, you helped build the Funnel office with Patrick Jenkins, Adam Swica, Tom Urquhart and Peter Chapman.

Frieder: We built the Funnel office during the summertime when the theatre was closed, it was a lot of work. I wasn’t much of a carpenter but I could bash in nails. Show me what has to go together. There was another fellow, a blonde haired Australian, David Bennell, he was a carpenter. He knew how to put all that stuff together. It was good we had a couple of guys who knew what they were doing because a lot of us were flying by the seat of our pants.

Mike: Did you go to many screenings?

Frieder: Oh yeah, we had some great programs. There were a lot of travelling filmmakers who came through. There were also special events. The front office/gallery had filmmakers show some of their visual art. There was usually something happening every weekend, you had to drop by. I went every week when I could.

Mike: Did you see video in the Funnel theatre?

Frieder: Yes, video was a new thing. Where is this going?

Mike: Did your movies tour with other Funnel films?

Frieder: Once or twice. I remember some of the members going down to the Ann Arbor Festival, but I didn’t have time to join them.

Mike: There was a lot asked of the membership in terms of volunteer hours.

Frieder: That’s the only way it worked. It was totally volunteer. It wasn’t until we had funding from arts councils that we could afford to have someone on payroll. If you’re passionate about something, it doesn’t feel like work. We were a bunch of friends. It was a very rewarding and wonderful time of being exposed to film and making film art. But I think it’s very difficult to sustain something like this over a period of time without bringing in a lot of fresh blood. I ended up moving away in 1982-83. Even before that I no longer had the time to spend over there because my professional life was starting to take over. If you want to have a bit of a social life and have a spouse, it does take its toll.

Mike: The Funnel wasn’t only a film theatre, it also featured production and distribution.

Frieder: The Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre wasn’t living up to its mandate. Filmmakers had to submit their work, and the CFMDC staff would decide whether to distribute it or not. If they felt there was nothing they could do with the film, or that it was too experimental, or that no one would be interested in it, they wouldn’t take it on. I knew that pissed off people at the Funnel, that’s why we started looking at alternate means of distribution. We started to distribute our own films, and put out catalogues. I know at one point there was a question of what films do we want to accept, what films do we want to distribute? I think the Funnel fulfilled a need in the community at that time.

Mike: Many people at the Funnel didn’t have kids, did traditional family structures conflict with the values of the group?

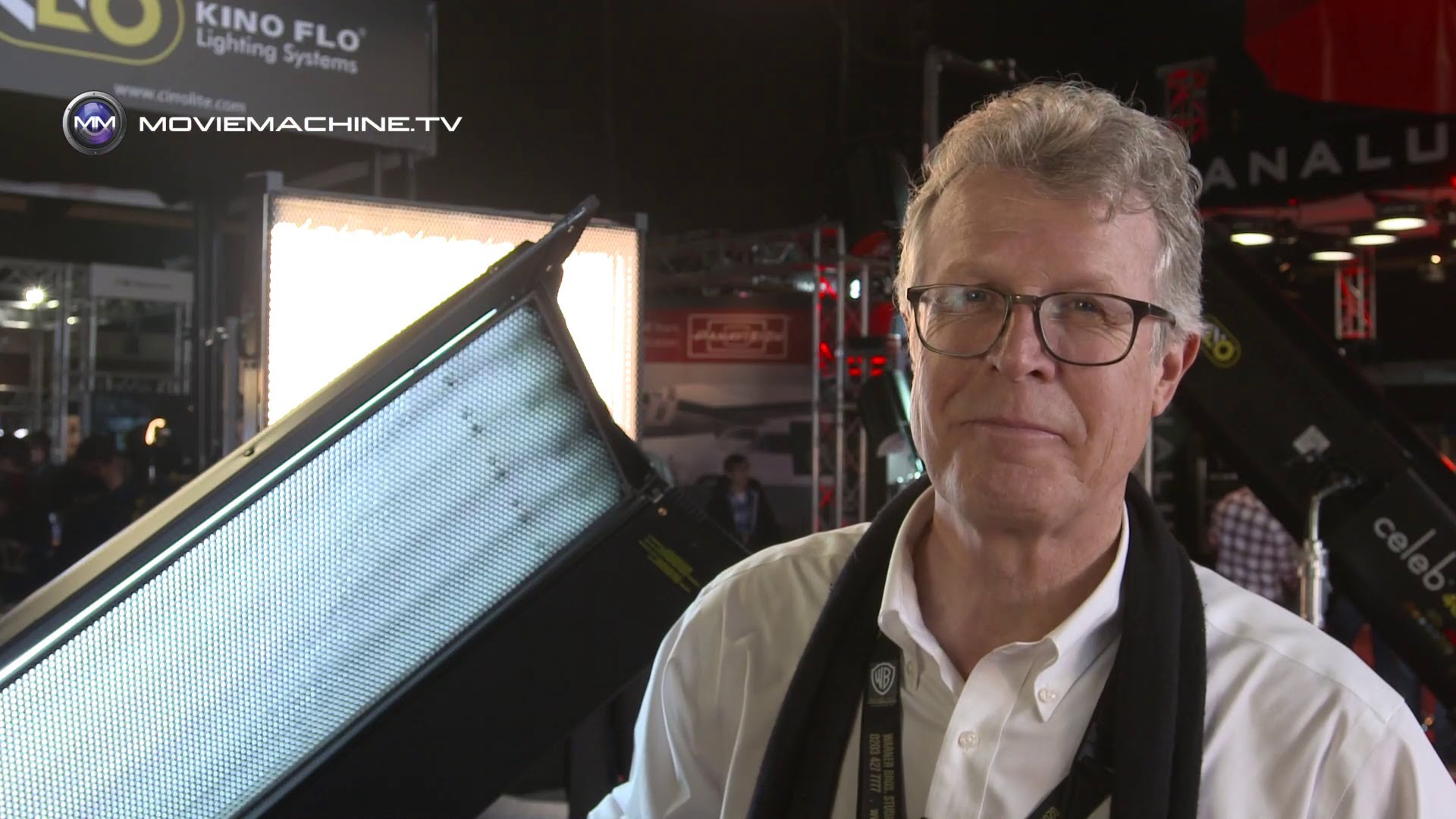

Frieder: That may have been some of the thinking at the time. The last thing on my mind was having kids. It’s not until you develop as a person and you get a different perspective on life… I was a student making experimental films with this art group that I loved being around. Then life evolved. You fall in love and share your experiences and opportunity presents itself and you follow that path. Let’s see where this road takes us. For some people having children would be an impediment to pursuing their art. I never saw it as an impediment, it was just another choice. My wife and I didn’t have children until 1986 when we were here in California. It was a motivation to pursue this idea I had about lighting.(founded Kino Flo Lighting Systems) Working fourteen-hour days in the film industry it was challenging to have a family, even sustaining a relationship. When the kids came along that was a surprise, there were twins. I decided to pursue the lighting gig and see where it would take me.

Mike: Did the film industry and the Funnel feel like completely separate worlds?

Frieder: Absolutely. I think the Funnel was a rejection of the commercial world. If you’re working with paint and a brush you could be painting houses and still paint canvasses, it’s the motivation that’s significant, that’s what separates the two. If you’re filmmaking and going commercial and still think that you’re an experimental artist, that’s a challenge because you need acceptance from the commercial community. I never made any bones about it, I could make some pretty decent money working in the film business whereas I know I’m not going to turn a dime doing art.

Mike: Can you tell me about your films?

Frieder: Plurality of Vibratory Circumstances (10 minutes 1976) features a schizophrenic conversation I have with myself. One self was on the rooftop of my apartment building, and the other was in an automotive scrap yard. I set up a rotation of cameras where I’m talking to the camera reciting sections from John Cage’s book M: Writings ’67–’72. I would open a page and stab a finger into it and write down what the text was. I compiled a couple of pages of these random phrases and when I looked at it I thought this actually almost comes together as a conversation. I decided to have an absurdist conversation. I would talk to the camera, and then to make it more interesting, the camera moves clockwise on the roof, counterclock-wise in the junkyard. Then I added a second camera in each of those locations, moving in the opposing rotational direction. The second camera was just a handheld Bolex, there was no sync or anything. I cut the whole thing on a moviola, a helluva job, and it became a symphony of camera movement.

Accumulative Distinctions Extending a False Utility (8 minutes 1977) was also an anxiety play. It’s based on a text from Kurt Wagn read in German, ‘Design of a General Theory of Consciousness.’ I had Tom Joerin (now a well known film editor) read the German phonetically because he didn’t speak the language. It was a discussion of being. “Being is not not-being.” The text recalls Gertrude Stein. We shot in the back alley up against a wall and I juxtaposed his reading with characters moving through the frame. It was an anxiety play with movement and sound effects and characters moving through the frame. In the background there was the sound of a trash truck, there’s a lot of interesting things going on. It was similar in spirit to something that Wim Wenders would have done where he does a tracking shot towards a juke box. That was fun to do.

I submitted Accumulative Distinctions to the Art Gallery of Ontario who were choosing Canadian experimental films for the Edinburgh Film Festival but it was rejected by the AGO curator. Then my school Ryerson was asked to submit a couple of films to the same festival and mine was chosen. The curator of the AGO festival saw it in Edinburgh and a year later he did a Dadaist show with some pieces of Kurt Schwitters , and he invited me to show this film as an homage to Schwitters. So it was finally shown at the AGO. They may have even paid me for it. The National Gallery of Canada eventually purchased Plurality of Vibratory Circumstances and paid me $900. It was part of a collection of 10 films representing the Canadian Avant Garde Cinema from 1976. It included a piece by Michael Snow and another by Dave Rimmer. Both artists has also been presented at the Funnel. That was the only money I ever made from one of my movies.

At that time film screenings were non-existent except for students showing in universities. The Funnel was the only place in Ontario that I knew of, there were no independent film screenings available. And the fact that the Ontario government was trying to weasel their way in to a small group of artists who were just showing stuff… it was so absurd. The Censor Board wanted to prescreen work in progress. If someone walked in with their little reel of 8mm film, some stuff they shot that afternoon, the Board still wanted to screen it. They were determined to bust our ass, trying to make some kind of point, I don’t understand why. I remember Bruce Elder was ready to take them on. He was ready to photograph his dick and project it but we talked him out of it. We said: this is what they’re looking for, this is the last thing we need now. We weren’t into making dick movies, we were just expressing ourselves in film. The Censor Board worried that there was some kind of pornography going on. They were off the wall. There was no pornography, it was just a bunch of film artists doing what we do.