Jorge Lozano introduction

screening of Fields of Presence, a feature doc about his daughter Breanna Lozano

Innis College, Toronto, November 2, 2024

I’d like to acknowledge that we are meeting on the stolen territories of the Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, Huron Wendat, the Petun, and most recently the Mississaugas of the New Credit.

Thanks to John Greyson for helping to make this screening possible, and for continuing to open doors that bring art and activism together. Over the past year in Palestine we have seen the systematic destruction of a people, an echo of the way Indigenous tribes have been treated in this country, and across the Americas, little surprise then that the genocide continues to be supported by western leaders. How to find the words, how to search for an image, what to do with these hands, while the genocide goes on, day after day?

Jorge Lozano is neighbour, friend and family. Canadian media art is filled with family stories. Could we call them home movies? I’m thinking of Richard Fung on the way to his father’s village or Steve Reinke’s father travelling the dominatrix circuit in southwestern Ontario. Yael’s lessons for polygamists, Alexandra Gelis remaking family in the light of her mother’s cancer, Phil Hoffman’s schizophrenic uncle creating a new kind of mirror, Julietta Maria licking the face of her mother. In tonight’s feature-length documentary, Jorge mines a lifetime of picture making, created in a blizzard of changing styles and mediums, creating a portrait of a city in transformation, a family in flux, and a daughter who turned her wounds into music.

When Jorge arrived in Toronto in the 1970s, barely fluent in English, he took a variety of bad jobs he was finally able to escape through artmaking. If leaving home was his first reinvention, making art was the second. The bad jobs, the uncertain language skills, and the place he used to call home gave him x-ray vision. He could see the way whiteness created cities in its own image, how power and privilege walked together like brothers here. He latched onto the idea that different forms, different kinds of media constructions were necessary, in order to create different communities. He learned language in order to undo it. And like many immigrants before him, he worked really hard. He has made more than 150 movies, more than half of which have never been shown publically. When I encourage him to submit his work to festivals his face asks me a question without having to say a word: do I look like I was born to fill out forms?

Tonight’s film began with a late night phone call from the Toronto police. That call was a door he was pushed through, and on the other side everything he thought he knew became a question mark. He began sorting through his own media rubble, searching for traces of someone who could no longer make themselves visible, for a voice that could no longer be heard. He had just returned from months spent walking with two dogs in the jungles of Costa Rica. They had became his spirit guides, and in watching this film, they become our guides.

To everyone who came tonight. To everyone who couldn’t. If only we could tell you how much we needed the warmth of your company, the sound of your attentions. Particularly tonight, which is being celebrated all over South America as the day of the dead. We hope you enjoy.

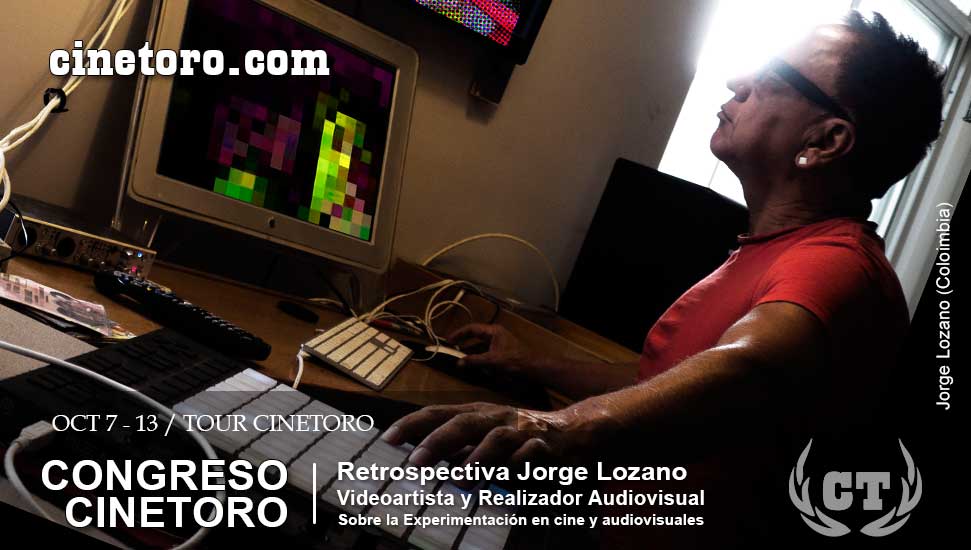

Be Realistic, Demand the Impossible: an interview with Jorge Lozano (2016)

Mike: I’m not sure how I missed you all these years. It’s as if we’ve been working side by side but I never learned how to look up, I never knew there was another direction. And now this new wind. I wonder if you could take me back to a moment in that other, unimaginable country, the Colombia of your youth. Can you return us to a memory, not one that stands in for all the rest, but whatever rises to the surface as you read this, from your earlier days?

Jorge: I remember many times laying down on the grass of the little park in front of my house in Cali, looking at the full moon. The full moons are gigantic there. You can see the craters with your naked eyes. Looking at these pockmarked landscapes I used to imagine my life away from Colombia. I always wanted to go away. Thinking of the unknown and unexpected excited me, it was better than the routine of being in the same place all the time.

I used to imagine my future apartment with everything inside, what color the walls might be, my books, my lovers. I imagined my life until the age of forty, which was my limit. When I turned forty, I realized how closely I had already imagined my life. But I never had an idea about what lay after that moment; and since then, I have lost the capacity for long range dreaming. So I started imagining my life again, this time day by day.

Mike: I’m wondering why you didn’t try to get along a little more and marry the dream of dominant cultures like so many others. Why didn’t you fit in? I sense in your work a necessary gap or separation between dominant cultures and your viewpoints. Can you point to an incident, a turning point, a place where you felt that separation, even learned to cherish it?

Jorge: Because I came from a popular neighborhood in Cali, Colombia, a racially and culturally mixed place, my commitment to change was focused on class struggle. I thought that everyone was equal and that fundamental differences were only between rich and poor. When I came to Canada I started to learn that there were other differences. My only references to Latin America here in Toronto were the alleyways and the native peoples. I directed a film called the The Three Sevens (24 minutes 1993) dealing with these displaced feelings.

The separation that you mention between my viewpoint and dominant culture is a “natural” gap. There is no way that I could assimilate to another culture. I have lived through American interventions and dictatorships in Latin America. I come from a country that has been in a civil war for more than fifty years, with the direct involvement from the USA. Canada is one of the western powers that has sided many times with the violation of human rights, and supported corruption and violence in our countries. For me, it is very easy to separate the world into the privileged north and the colonized south. I belong to both, but I am with the oppressed, silenced, made invisible and excluded people. I still believe that it is possible to break down the hierarchies that keep us apart, and that keeps the north ignorant about the cost of their privilege.

Locally, the divisions that I’ve mentioned are reflected at all levels, including the art community. The situation here is more complex; I live within the matrix of power that separates us, and that controls us, no matter what color we are. And that also controls knowledge and subjectivities. Maybe as artists we should pay attention to where are we located in the matrix. Maybe we should learn border thinking, transversal cultural explorations, and wear the other’s shoes at least once.

Mike: Could you say a few words about The Three Sevens?

Jorge: It was made in collaboration with Alejandro Ronceria; we shared some stories and decided to make a film about them. He acted and I directed. The intention was to make a film shot in places that looked like Latin America, so we headed for the alleyways in Toronto. Our main referent here was always Native culture, because we’re from mixed backgrounds. Judging by my family we are a blend of three racial groups — Indians, blacks and whites — that have mingled throughout the nearly 500 years of the country’s history. Recognizing the impossibility of objective racial classification and not wishing to emphasize ethnic or racial differences I am a celebration of the mix. Canadian Natives recognize us as native as well, they are the people we identified with when we arrived. Through contacts with native cultures here we learned that this is one continent, and that the absurd divide between North and South America is deeply related to economic privilege. Native cultures unite the continent and the film tried to capture that.

Today the film remains beautiful if naïve. Cameron Bailey programmed it at the Toronto International Film Festival and wrote a very nice synopsis. It was made for $20,000, shot by Kim Derko, a great cinematographer, and the crew acted as the cast. This is the reason why we were able to do 21 one-minute scenes in different locations with different actors. It was fun doing it, there were so many people excited about learning how to make a film and how to act. I myself got tired of working this way. It is very difficult working this way to finish a film as you really want. Too many compromises have to be made, and in the end you are left with a truncated vision and an unfinished film that conforms to its difficulties. It’s frustrating. Our independent media work can be very Lacanian. We always lack something to make or to show the works. I feel the same way with video installations these days. I am making multiple-screen HD works that are almost imposible to show. I feel like opening my own space to show my work and other works that I find challenging. We can always get what we “need” but not what we want.

Mike: The cinema of difference, the sense that something else could be done with movies, however did it occur to you?

Jorge: In Cali’s Goethe Institute I discovered personal filmmaking. It was shown in small rooms and mixed with the mechanical sound of the projector. They were short films shown to smaller audiences with everyone sharing these intimacies in the dark. There was not one film, but many diverse, high contrast, 16mm films gathered in a program. Short films were a new form of expression, rhizomes spreading across new territories, nomadic, always unfolding, and above all, personal, intimate and unbound from producers. Underground!

From this fragmented cinema and its broken narratives, I learned fragmentation. I began to see the worlds inside and out as a multiplicity. I understood that action arrived as both reaction and creation. Looking back, I can see that I was still dealing with fragmentation in a linear way, imagining my work and identity as a single trajectory. I was still a follower.

My strongest encounter with personal, experimental cinema came one night in Cali, in the same theatre where I had seen the plays of Brecht, Ionesco and Artaud. There I discovered the 16mm films of Canadian artist Norman McLaren. They were about light and movement where streetlights became forms, cities became shapes. These non-traditional narratives presented a radical rupture, unknown to me, because I was always looking for the meaning in everything. Of all the influences I had at the time, this was the one that marked my life and the work I was going to make in the future. McLaren taught me that night that filming can be a visual experiment, and that pictures have a life of their own. Form can be its own content. It was the pleasure of making these shapes with a camera that fascinated me. Images staged their transformation from mere copies into collective amalgamations of flows, dancing particles of light rhythms.

In my early super 8mm films I tried to imitate these films or my memories of them. In 1978 on Yonge Street, using my Canon 814 loaded with Ektachrome (nice reds), I filmed the circular “Sam the Record Man” light bulb sign. With only the magic of my hand movements, I converted these lights into spirals and colourful zigzags, spontaneously action painting. To my surprise these largely forgotten three minute reels of super 8, reminiscences of a priceless time, will appear again in a new movie I’m working on called Situations. It will feature an assemblage of material made from the 1970s to the present reflecting on decades of queer rights struggles, feminisms, civil rights and anti-war movements. They are a reminder that too little has changed, that each escape route becomes another threatening entity. Protest has to beyond being a process of declaration and we must become political subjects again.

As an artist one of my central concerns has been how to implement the concept of self-organization in my practice. In my personal life this means expanding the recognition of differences, and to embrace the collective initiatives of those delinking from status quo imaginations. “Self-organization” is a term taken from biology where complex systems result from several simple elements executing local behaviour. Self-organization is the creation or participation in groups/ideas/networks that share similar concerns and allow each of the collaborators to create our own rules and to interact with the others to sustain the network without losing autonomy. At an artistic level, self-organization means the production of works where images/ideas are positioned together to create multiple connections, while at the same time preserving the self-sufficiency of those images or ideas.

The meaning of “to be influenced” or “to influence” someone can be placed within this definition of self-organization. Influences are non-linear dynamic exchanges, they are border crossing experiences. To be influenced is to find connections with artists that excel in their exploration of autonomous thoughts. We live now overfed by the surplus of the spectacularization of art. We are drowning in the “waves of enthusiasm for a given art (new) product.” To continue remixing Debord’s ideas: the spectator has been drugged by spectacular images that we can change though radical action in the form of the construction of situations, situations that bring a revolutionary REORDERING of life, politics, art and decolonization of aesthetics from the subjugation of the optically correct. The monopoly of information is perfectly synchronizing human emotions, smothering the truth of facts and violently erasing other possibilities.

Mike: What used to be called “experimental film” left its mark on you.

Jorge: As I rewind over this long history of influences I remember innumerable cases where experimental, underground filmmakers broke rules to focus on new perceptions, throwing cameras out windows to experience the vertigo of falling geometries, the speed of oscillating white frames producing epileptic fits in the audience, painting directly onto the film in search of new concepts, rhythms, light and textures trapped in the celluloid. I remember one of Stan Brakhage’s films used a fixed camera to record the birth of one of his children. Raw cinema. Many years later I found myself photographing the same process with the birth of my own son.

Mike: If fringe movies were determined to make us look twice, to show the act of looking itself, video seemed aimed in a slightly different direction, at least at the beginning.

Jorge: In the mid-1960s a seeing and thinking revolution was brewing. The Sony video Portapak had arrived. It was a portable video camera cabled to a heavy recorder that allowed viewers to see recordings in real time, or with a small delay undetected by the human eye. Instant replay was a blessing for activists. The information could be recorded and replayed immediately, and it could be moved around and shared with other activists. It was an alternative to the monopoly of right-wing broadcast television and a tool to fight sexism, racism, war, and homophobia. Using portapaks, artists from all disciplines started to explore new ways to intervene into galleries and other public spaces.

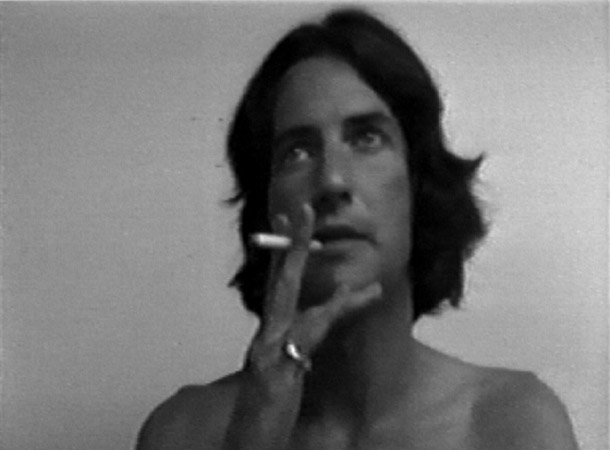

The first artist I met in Toronto was Colin Campbell. I was an immigrant willing to work at whatever job I could get. We were hired to do election surveys in Ontario, knocking on door after door asking owners or tenants if they had registered for the upcoming election. It was another one of those mind-numbing Ontario elections where mostly it doesn’t matter who gains power, the government changes very little and we manage to survive them. It was a tedious job that paid perhaps four dollars an hour. Colin was bored and uninterested but I enjoyed everything, particularly the smells emanating from the houses, each one as different as the people who lived there. It was fun. Most of the people were Polish or Portuguese elders who hardly spoke English. I still feel dizzy and nostalgic imagining their uprooted lives, their loneliness, and their foreignness.

Colin and I walked slowly and talked a lot to kill time. My encounter with Colin was of those situations where you “meet someone” before you really meet them and they subtly affect you in unrepeatable ways, no matter how many future encounters occur. At the end of the day he invited me to his apartment to have orange juice. That day he showed me one of his videotapes. He was walking naked in front of a window talking, as he always did in his work. Everyone talked to the camera in those days. The tape showed him walking naked in front of a luminous window. It was so simple and so complex; an instantaneous and self-made work using the monitor as a reference for movement in space. I was profoundly moved. I remember leaving his apartment thinking about the beauty of the portapak’s black and white light embedded in its cathode-ray tube. You could literally write and inscribe words into the tube if you aimed it at a light bulb or the sun, such was its sensibility and fragility! The light wrote images on the tube and the camera stamped those images on magnetic tape. It was a different way of seeing that only artists understood as an aesthetic alternative to the expensive and complicated system of filmmaking. I left Colin’s apartment wanting to make tapes about myself. I wanted to be my own subject, not an actor. I experienced a radical phenomenological shift. I started to look at the outside and inside worlds from many angles, my surroundings presented themselves via multiple perceptions. A “seeing and thinking revolution” started when I began to use portable video. Working in real time was an invitation for self-observation, and to reimagine the body of the artist. Talking naked in front of the camera offered new possibilities and approaches.

Because of its low costs and portability, video slowly become an expanded form of cinema, and built its own language. I arrived in the late 1970s to join this process, as part of a generation of young artists seriously at play, carrying these heavy machines to record ourselves and our precious time and space. We included the errors inherent in this analog, electromagnetic, reel-to-reel technology. We lowered the quality by making second, third, and fourth generation copies of the same image to attack the image and sound. Risking the information, we increased the medium’s vocabulary until it eventually became repetitive, tedious, sometimes difficult to see. We weren’t afraid to risk failure in the hope of inventing something new.

I left Colin’s apartment thinking about the beauty of the portapak and the black and white light emanating from the monitor. Instead of the transparency of film, this was like a light reflecting from a phosphorous cloud, an x-ray of real time. The search for real time brought intimacy and a new distance. Ironically, in the years to come (at the present moment for instance) our technologies of speed and instantaneity have exiled us to a new electronic privacy.

The portable video camera was developed by the American military so that it could be used as surveillance and recording equipment during the Vietnam War. In our hands it became a tool of resistance that helped transform our perceptions and aesthetic concerns. With the portapak we started to understand the mechanisms of bio-political technology used to control populations by regulating information. We had to be realistic, and demand the impossible.

Mike: You have feelings about dogs.

Jorge: I never liked dogs. Actually, I do like dogs, I have nothing against them, but I hate the relationships that humans have with them. I feel that dogs are filling a void made by our separation from nature. Dogs have become a kind of prosthesis, an artificial limb of this existential loneliness. Dogs are controlled, subjugated, brainwashed. They are killed by human love, kisses on the mouth, and stinky dog cookies. But when I see again William Wegman and Man Ray (his dog) in Spelling Lessons (1973) I accept that I am temporarily wrong. Dogs are smart and can become artists.

Mike: You spoke about finding a clutch of black men lying dead on the railroad tracks. Could you return us to this encounter? Are there other moments in your life when you have confronted the dead and dying so directly? You mentioned, almost casually, that because you grew up in Colombia, seeing dead people on the street wasn’t so unusual (or am I grossly mis-remembering this moment?)

Jorge: It was a sunny day and I was going to school after a heavy tropical storm. The city was clean and the leaves in the trees were transparent, bright, intense, green. Everywhere was immanence. The clouds were moving rapidly, panning sunrays over my section of the city, my field of vision affected by this constant expressivity of shadows and bright colorful zones appearing and disappearing. I was euphoric. The city and its people became present and ephemeral at the same time. Everything around me was alive, except for these four or six naked black men, piled up dead in the back of a track. They had been thrown on top of one another. A black mass of clumsy legs and twisted arms. Hardly human. I was in a hurry and didn’t want to stop to look in detail, but one of them made eye contact with me and I still remember him. His eyes were dead. But his body was alive with the sunlight reflecting from his swollen belly and stretched skin. The flesh was transparent and colorful like a clean aquarium. I remember how this beautiful purple and lemon-green changed hues and shades with the moving clouds. “Why are they here?” I asked myself. Such lack of care. They should be taken away, I kept thinking, as I walked on. Though if they were moved, most likely they would explode, their guts would burst through that beautiful skin.

How can I see such horror and think about beauty? What is so horrible about death? Death is the end of men and men are the death of the world. It has been normal to destroy and create via the ruins of others in the name of progress. The exploding and flying limbs in World War One inspired Cubism and Bio Art. Body modification started during World War Two in Josef Mengele’s labs. Aesthetic concerns have surrounded death how many times? Of all our histories, the history of cruelty emerges as a winner. How could I see horror and think of beauty? I know that I was in a hurry and it was such a beautiful day and they were already dead and there were so many deaths all the time. Natural and unnatural deaths. Good old death has been the Colombian’s most powerful landowner for the last fifty years. Death has no limits, but it can choose, and obviously it takes the poor and the rebels first. Death has sided with the rich and allows them to stay longer so they can help him do his job. They play the same music.

I know death has always been travelling back and forth from the United States, his place of birth since 1850, when it came in the name of William Walker, the Gray-Eyed Man of Destiny to invade Nicaragua. I wasn’t sure if death worked for the Americans or the Americans worked for death. I only know that I’ve seen and heard of so many deaths that four or six more dead men were not my concern, only the beautiful one with dead eyes. The one that I still remember.

Colombia has been at war for more than fifty years. Recently the guerrilla army and the government started peace talks. The reason for these wars is inequality. A large population of people are ruled by a European-educated class of rich people who unbelievably cannot see the damage they have created. Adding fuel and weapons to this war is the economic, military and political control that the USA and European countries exercise over our governments who sell out our national resources. I don’t say they kiss ass because kissing an ass is not that bad, but certainly they don’t have a mind of their own, or ethics, and are absolutely despotic. There are two ways to create wars when you are a superpower. You make sure that people in other countries fight to death, or you invade the country and impose whatever you want. Superpowers think that they can live happily ever after and never deeply question their privileges. Until their empire implodes.

But the real reason I did not pay more attention to this group of dead men was that if I had stopped too long, I would have died with them, or at least I would have been left feeling their absence, and grown a phantom limb. I still live with the absence and the presence of friends, teachers, humanists, philosophers, actors, writers, and poets, activists who were killed. For what? If nothing has really changed?

Mike: You’ve cited Béla Tarr’s slow motion Turin Horse (146 minutes 2011) as an influence in your work.

Jorge: The film refers to a story about Nietzsche in Turin on January 3, 1889. Friedrich Nietzsche steps out of the doorway and not far away, the driver of a hansom cab is having trouble with a stubborn horse. Despite all his urging, the horse refuses to move, whereupon the driver loses his patience and takes his whip to it. Nietzsche comes up to the throng and puts an end to the brutal scene, throwing his arms around the horse’s neck, sobbing. His landlord takes him home, he lies motionless and silent for two days on a divan until he mutters the obligatory last words. He lives for another ten years, silent and demented, cared for by his mother and sister. Thinking about Friedrich Nietzsche’s and the horse’s vulnerability brought tears to my eyes.

Turin Horse starts at an impoverished farm occupied by an elderly man named Ohlsdorfer and his unnamed daughter, who are trapped in the winter along with their unnamed horse. The horse is kept outside in the cold and is slowly giving up by refusing to eat. The film is about repetitions, and the extreme routines of an unadorned existence. Outside the house we hear the relentless roaring of the blowing winter wind. I started to think that it was important to create works that have austerity, works that could capture the solemnity of nature’s inhumanity. A few days later I went to La Guajira, a deserted and inhospitably beautiful land in the north of Colombia, inhabited by the Wayus, the people of the wind, sand and sun. The never-ending wind became central to my film Kuenta. Like in Béla’s movie, I wanted the wind’s eloquence, minimalism and endurance, it became the conveyor belt that kept everything moving and transforming. My head was flying, lightened by unconscious non-literal references that made me aware of a deep existential angst caused by the inexplicable permanence of the wind constantly howling. The inexorable states that shape our lives! Kuenta is about an indomitable landscape and the horror hidden beneath the beauty of its surface. A continuous becoming in a land that appears to be unchangeable, but is ruptured by unspoken political violence. In the end everything was linked in this magnificent terrain; subterranean and forgotten ghosts came back to light, ghastly stories arrived amidst the beauty of this sublime land.

Mike: In this double screen installation there are pairs of looking, like two eyes, comparing and contrasting. On the left screen an old woman and a young girl place sticks into a sand pile, while on the right a hand plucks out cactus needles. On the left a superimposed target moves across an emptied landscape. On the right the wind blows against the rocks. And inside this landscape you perform actions and interventions.

Jorge: The most beautiful hammocks in the world are made on this peninsula. They’re so expensive it’s hard to buy them, people purchase them as a demonstration of status. The people here are amazingly talented at textiles, so some of the actions that we performed involve textiles. For instance, stretching threads of yarn into the desert. Threads of thought, of stories, of lives. The land has a lot of coal and sea salt and this has caused problems because multinational mining companies were interested in exploiting these resources. As usual, this led to paramilitary forces arriving in order to displace and tyrannize the local population. They killed the women first because women are leaders here. We show pictures of kids pretending to shoot each other, falling dead and celebrating death. They act out some of the violence that is stirring in their collective memory.

Keunta has no dialogue and a melancholy pace that creates a hypnotic, paralyzing story. It unfolds in long, slow, elaborately choreographed instances. The word Kuenta in Wayuu means to tell layered stories. The ritualistic repetition of actions, the fixed camera that maps out the forms of this enclosed but oddly expanding universe, and the eerie, low frequency sound design enhance the monotonous and repetitive actions that we found in the people who live in this windy coastal desert — fishing, weaving, surviving, resisting and reproducing. Out of these everday gestures, these singular instances, I find moments where existence and mutuality is reaffirmed and redeemed. Kuenta combines the recordings of daily activity with artistic interventions to re-create local stories. Kuenta is about simple acts of emancipation initiated in the routine and endless tasks of daily survival. Landscape becomes a metaphor to pay homage to the resistance of Wayu women and to those who were assassinated in Bahia Portete , April 18, 2004 by paramilitary forces. (Kuenta was made in collaboration with Alexandra Gelis. I’m only writing my personal view of the making of this work).

NaCi (14 minutes, double screen installation, 2012) is a two-screen video installation that makes reference to the ancient salt roads and salt industry. Salt was central for the making of the European empries, allowing them to change salt into gold. People from La Guajira make sea salt. Colonial division of labour has ensured that their living conditions have hardly changed. Of course they can vote now, but they still work fourteen hours a day earning low salaries for this painful labour. The word salary comes from the Latin world salarium, which means payment in salt. A far-flung trade in ancient Greece exchanged salt for slaves and gave rise to the expression, “not worth his salt.” The trading of gold for salt has paved the way for the expansion of “western civilization,” colonialism and the rise of military powers. NaCi visually retraces this history using as a backdrop the bone-breaking, low paid work of the Wayuu people in the sea-salt mines in the north of Colombia along with some of the most often cited salt quotations from antiquity.

NaCi is the third in a three-part series called The Business of Spaces. The second part of this series is a multi-screen installation about potato fields in Columbia called Forests (7:28 minutes three-screens, 2012). These fields are largely deforested now owing to overcultivation. The tape shows the beauty of this land, which persists even through its deforestation. This beauty, for me, is already a kind of resistance. Along with the potato and cattle fields in Cundinamarca, there are also the ancient fields of the frailejón in El Páramo del Guerrero (alpine tundra ecosystem). Bathed by the changing sunlight, Forests presents a topography of human redundancy and the ongoing resistance of organic forms. “A rugged reality embraced.” (Arthur Rimbaud)

Mike: Your genius four-screen installation Watch My Back (2010) offers us a quartet of portraits. Each subject stands with their naked back to the camera dishing a subtitled monologue about their life. Pictures float past each of them showing bridges, tattoos, housing project exteriors, often via slow moving pans. When you showed it off at York University, they were laid up on four small screens one beside another, like a quartet of stand-ins. It is a documentary spread apart in sections, scene after scene. It is detailed, devasatatingly emotional, and lyrical in its treatments. The first soundless speaker has come from Nicaragua, and crosses illegally into the US border, but not before being abandoned by his faithless coyote guide. He finds grinding poverty in America, and chooses one of twenty schoolgangs to stop the beatings from blacks, Chicanos, Mexicans. He takes up “street life” as he calls it, and rises from soldier to captain to general, watching so many die, and then does serious jail time where best friends turn sour over a toothbrush. However did you find them and get them to speak about these dangerous intimacies?

Jorge: Watch My Back was the result of video workshops I’ve conducted in Colombia and Toronto to help youth from under-represented communities produce their own work and possibly initiate a creative career. The focus is on aesthetic quality, conceptual depth, and developing appropriate levels of technical proficiency.

Watch My Back is a poetic explorational documentary about the lives of four young people who grew up in Toronto ghettos. In each instance their family was forced to come to Canada due to civil war displacement in their countries. The installation focuses on neighbourhood architectures, as well as the social/cultural spaces they inhabit, the resistance and creativity they expressed while in jail.

I started to think about the project while facilitating a video workshop here in Toronto with youth from the sometimes difficult Jane and Finch neighbourhood. I had previous experiences creating a documentary installation with some of the members of a video and sound workshop that I was facilitating in Colombia and wanted to do the same in Canada. I wanted the workshop participants to have a dual creative role as subjects and producers. As I grew more knowledgeable about their physical and cultural surroundings, I began to visualize a video work that might recreate my feeling of immersion into their environment and also become an intimate testimony of their lives Watch My Back is the product of a collaborative process. It was important for me to work with them as colleagues. The participants recorded their own neighborhoods, hangout places, homes and bodies. The project offered a way of affecting local situations using self-learning and self-representation to produce change in places where change seems impossible and youth have minimal resources.

I grew up in a popular neighborhood in Cali, Columbia, surrounded by houses of prostitution on each corner. The houses were run in most cases by transsexuals. Often there were fights at night when the transsexuals were uncovered, having fooled clients with their feminine mystique, or else clients refused to pay for services already rendered. There were many gangs in each neighborhood and fights between the gangs were frequent. The gang in my area was called the Vampires but because I was little I was forced to be in the Golden Warriors. The gangs were structured like the military, with generals at the top, and soldiers at the bottom doing all the fighting. You didn’t need to be too smart to realize that there wasn’t much freedom in this organization. Perhaps as a result, freedom became a preoccupation in my life, I didn’t believe in anything, and had thrown “god” out of my life because “his” authority simply shrank my possibilities. In this period I became aware of the importance of self-learning and self-representation. Half my friends became criminals and died young. The other half were able to hook into the expressivity of popular and unpopular cultures and its capacity to create resources out of nothing. They became artists, although some of them also died young because of their involvement in radical, left wing politics.

Life in underprivileged communities revolves around violence that is both more visible and frequent than in better-off communities. Youth in economically poor communities have two options that are both very creative but achieve opposite results; they can be outlaws or seek creative expression. Being good is a third option that sometimes leads to apathy, powerlessness and being comfortable with a repetitive, servile life. The friends who influenced me the most were those who maintained their independence from the gangs and who saw many dimensions within our own territory. They did so by sharing new informations and new ways to see the familiar. I left my neighborhood many years ago and changed my life without losing my independence. But the neighborhood never left me. These video workshops are a way to return.

Watch My Back is the continuation of a seven-screen video installation that I made in Colombia called Moving Still-still life (33 minutes, 2007). Both works share similar conceptual and aesthetic concerns and emerged from collaborations. In 2007 I was back in Cali conducting workshops, greatly impressed by three of the final fiction projects made by youth participants. Each dealt with the difficulty and uncertainties of making decisions in a hostile environment. They were called Ese No Era (He Wasn’t The One), Impacto (Impact) and Misterio (Mystery). I realized that they all had a common thread; the representation of their lives was surrounded by violent imagery that was used to inquire into the violence itself. At the same time the existence of that violence and its resolution in fictional settings was seen as a way of holding and escaping it. This observation prompted me to ask myself about the value of images when representing horror and their inability to go beyond appearances. Or could images represent material presence and create a discourse to encode and re-render history? Do images become a duplicate of the thing they refer to, or are they part of a transformation?

With these questions in mind I decided to work on a poetic experimental documentary about the life of young people living in Siloé, (a popular neighbourhood in Cali, Columbia) focusing on the social, cultural, conceptual, and architectural spaces they inhabit and their day-to-day existence and subjectivity. By “poetic” I mean a fresh and immediate approach to recording their visual and aural testimonies, exploring social divergences that have turned to cultural convergence, and, most importantly, offering reflective examinations of human potential. By “poetic” I also mean moving away from the artificial continuities of traditional storytellings and editing strategies that elide differences by emphasizing associative patterns. Instead, the approach would be fragmentary, impressionistic, lyrical. Furthermore, by “poetic” I mean taking images as navigational references and as a way to aesthetically reconstitute fragments of their “real world,” speaking directly to the viewers, in a non-authoritarian way, inviting viewers to make their own interpretations. All in all, I wanted to create a dialectically complex and multilayered hybrid, equal to the sum of my participants’ visions and my own.

Moving Still-still life documents the perspectives of seven people in Colombia whose lives are restrained by economic, social and political disadvantage. It is not a complete or unfinished picture of their personalities, nor is it a sociological or political statement; it simply encapsulates their sensibilities in one kaleidoscopic moment. It is a glimpse into their past and their neighborhoods, where the rhythm of life mirrors the random staging of their houses. It is a theatre of the unexpected, a gathering of culturally diverse people displaced by political violence and/or poverty, each one with her/his own stratagems, an architecture of survival built from “nothing,” brick by brick. Zigzagging structures of volatile conflicts are interpolated by direct responses and actions.

Their neighborhoods are culturally colorful, intensified by the complex vitality of over-population and an often debilitating lack of resources. They are divided into territories controlled by gangs or armed groups where death is almost a daily occurrence. This apparent subjugation or radical conditioning to violence is transformed when passivity or aggression is replaced with non-violent situations: cultural activities and self-sustained imaginative strategies. Their need to change remaps the imposition of danger, and repositions them as actors and/or intelligent spectators.

Both projects explore the intersections between fiction, documentary, experimental filmmaking and visual arts. They can be presented as conventional film or as an experimental “docu-installation” that occupies a space between cinema and the arts. The work mixes landscapes, graffiti, street life, interviews, and segments of experimental and dramatic works blurring distinctions between reality and fiction, documentary and installation. I wanted to be inside the convulsion. To follow the tempest blindly meant being indebted to authority and death. Life means a retracing, a redrawing of new zigzagging structures and situations, new ways to feel and to perceive labyrinths of signs.

Mike: Situations (34:45 minutes three-screens, 2012) is another of your multiple screen extravaganzas, this time reaching back into what appears to be an inexhaustible archive of direct political engagements, pride parades, intimate encounters, private gestures. It’s striking to see the variety of stylings so easily blended, from your super-8 embraces to a variety of video recountings. Can you tell me more?

Jorge: Situations is a mess of a film. It uses three screens to make a bigger mess. And the mess is that a lot of the issues that we have fought for haven’t really guaranteed social justice. Let me explain. We are relatively free in Canada, we recognize lesbian, gay, bi, transgendered rights, the equality of women. But we have supported governments that violate those rights. Being privileged in most cases is hypocritical, that’s all, it can’t be any other way. Economic privilege is a system of oppression. So much for true ethics. Poor Spinoza.

Situations starts with fragments from a super 8 film that I made with Rebecca Garrett about revolution as fiction. I was inspired by the work of Beth and Scott B, super 8 filmmakers from New York. CEAC (The Centre of Experimental Arts and Communication) was very active then. It was started in Toronto in 1975 by Amerigo Marras and his boyfriend Suber Corley. It was a gallery, performance space, workshop, library, punk showcase. They published via xerox issues of a zine called Strike which expressed solidarity with anarchists in Italy which stopped public funding and they were forced to close. The last time I saw Ron Gillespie was at the Scadding Court swimming pool. He could hardly talk and his eyes were blood shot. He was touching the fragility of life by taking rat poison in small doses. He wanted to get as close to death as he could.

Anyway, I took all the material I recorded since 1978 in super 8 and different video formats. Much of it showed public protests, feminist rights, gay rights, demonstrations against oppressive conservative governments. When I stitched them all together I didn’t keep the chronology, these moments of resistance are blended, because in the end I realized that we’re still fighting for the same things, or that each breakthrough becomes another threatening entry.

Like most of the work I do, this one triggered memories, memories that aren’t represented in the images, so I use text as a unifying device, and to fill in the voids. In 1978 I was at a rally in the University of Toronto’s Medical Building. The rally was in support for the people of Namibia, West Africa, who were fighting against apartheid. A white power group had infiltrated the event. At some point, one of them aggressively took his biker’s jacket off, and you could read the words “White Power” on his tight, white t-shirt, and he screamed, “White Power!” He and his friends started to kick men, women, children, everything. They had knives, baseball bats, chains and knucklebusters. They threw a can of tear gas and shot a pistol in the air. They beat up peole and sabotaged the gathering, leaving behind bleeding men, women and children. There were racist slogans in the city everywhere. This attack never really made it into the news. Perhaps there was a small paragraph in the Toronto Star. Such is our fascination with stars and life on other planets.

I started to mix recordings that I made in Europe, North and South America and Berlin when the wall was up. Europe was anti-Reagon and pro-Beatles. Sendero Luminoso was all over Peru. I was with Eva. Susan Britton was the best artist in Toronto. General Idea made Shut the Fuck Up, Andy, Robert and the Government were at the Cameron House. As the installation progresses, I continue mixing landscapes, faces and cities in an achronological mess. The seeing and unseeing happens at the same time.

I used to live around the corner from the Morgentaler Clinic where the first abortions were being performed in Canada. Here is someone holding up a “Canadian Abortion Rights Action League” sign. The clinic was bombed, and it’s amazing that in this country where the police know everything, they were never able to find who was responsible. It was such a professional job using explosives, and there are only a few professionals. The camera moves through crowds and faces. Here are the Bunch of Fucking Goofs, a punk band from Kensington Market, still goofs and fucking. They actually became more conservative as the years passed. When Vietnamese gangs moved into the Market I heard that the Goofs asked police to provide more security. It should be the other way around, as we get old we should become more radical, like Delueze. There are protests in Toronto and Montreal, and many gay marches. Selecting the bits from the twelve years recordings that I have of Pride Weeks became very painfuI because many of these people are not alive anymore.

Mike: Stratigraphies (48 minutes 2012) is a hyper-kinetic travelogue masterpiece offering glimpses of scenes shot in your native Colombia, New York, Toronto and more. A female fantastic (Alexandra Gelis) knitting on the fly (subways, bankomats, beaches) and making audio recordings provides a throughline of sorts, as queer marriages give way to videogame palm trees, warm gatherings of friends are interwoven with public noticings, workers mostly, street hawkers and construction zones of the self. What a riot of interdependence is on display here! Each gesture, each instant, feels like it is part of the next, as your sensitive camera work brings the world close enough to touch. A stunning overhead shot offers a pair of sex workers on the street, then a glimpse of Borges delivers us to sunbathers on a grassy knoll, where a very different kind of display turns the gaze. We linger on the saddened face of Alexandra Gelis again, as we are rooted in her subjectivity, the intimacy of the two of you as well, the consent to show and to be seen, and then we see a man plastering up a small building monument. He is constructing, but also somehow constructed by, this presenting façade. How much labour this architecture manages to disguise. Naturally enough, this flurry of seeings is followed by tracking shots of apartment buildings (which mutely ask: what have we become? why do we have to live in these warrens?) intercut with instants of a woman running, as if to escape these grim economies of space. And then we are back on the street corner in a recapitulation of the sex worker moment, but this time with your red-haired friend, who gestures back to you with her head as if to say: we’re in this together now, let’s go! In these few minutes you wordlessly contemplate the connection between bodies and architecture, how the spaces that we inhabit are also inhabiting us, and what it means to show ourselves in a privately public space. Your shooting style is a beautiful amalgam of video lyricism and some unmistakably shaky expressionisms learned in a particularly filmic avant-garde, but now bootstrapped with great elegance and electricity into the world of video. It is thrilling to see this unholy marriage of film and video sequencings, as if you’ve thoroughly digested the best and worst of two large traditions and then recast them in your own way with enormous freedom and fluidity. What a celebration you make of seeing. Please, tell me how you did it.

Jorge: Stratigraphies grew by itself. It was always there, flowing through every single work I made. I thought about making a large cinematic piece without using a script or a central conflict. I wanted to start the film using one image that would start an unfolding of unexpected assemblages. It all started by an accident. Alexandra Gelis was taking a shower, we had just arrived in Buenos Aires from a long bus trip from Cordoba, and wanted to get ready to meet Graciela Taquini, a great artist and curator. I turned on the TV and found Jorge Luis Borges talking about how, even during his time in Europe, he never really left Buenos Aires. As I started to record Borges, Alexandra came out of the shower and I started to go back and forth between Borges and Alexandra getting ready in front of a mirror. Initially I wanted to be the subject in the film, but instead it all started with Alexandra and Borges. Borges’ talk about being in two places at the same time (like in quantum mechanics) provided the conceptual starting point for the video film. I was supposed to have been the character but Borges switched it all.

Because Alexandra and I have travelled together many times, and because we are always recording situations, it wasn’t difficult to agree that from this found beginning she would be central to the recordings, and that she had to be herself and at the same time someone who would slowly take shape. The fascinating thing was that the person who was beginning to take shape began to look like Alexandra, while Alexandra was becoming the person that was beginning to take shape. Slowly this morphogenesis expanded into the surroundings. Every day we encountered new sites, we found theatres for these transformations as Alexandra and I let the video film inhabit us. We started to intervene in the spaces that we met, we spoke with people in the streets, visited galleries and works of art we found significant, and in the end we intervened with ourselves. This psycho-geographic experiment found us becoming unrecognizable in familiar ways.

During the videofilm Alexandra’s voice is her presence, and her presence reaffirms the fact that to exist is to have a critical perspective. To go beyond the given and the imposed. It is a work about both of us and about that person who is the assemblage of both. Our relationship is transversal, so the female and the male inhabits each of us. Stratigraphies is not about male and female. It is about joining our gestures to critique the complexities of being in a time of speed, global capitalism and a digital mode of production that shrinks our territory. Stratigraphies is above all about the pleasure of using images to create and unfold the presences of a rich history of experimental cinema.

With the increasing speed of tele-communications space shrinks and tends to disappear. Alexandra is usually in motion — she moves all over and she is in the same time/space — she stays still and she can be everywhere. Everywhere and anywhere is her home and is also the site of her exclusion. She resists disappearance by keeping creatively active. She doesn’t demand to be named. She is a character in a film and an assemblage of multiple traits. She is Alexandra the real person, she is Alexandra recreating Jorge, and she is an assemblage of Alexandra and Jorge. These three levels of existence create an identifiable character. The idea was to create the conditions for viewers to loosen all expectations about needing to know a personality and instead join her trip. Her gestures and expressions lead her, and perhaps lead us, away from the reductions of functionalism, from what is only useful. Her movement models a reorientation of assigned places and roles.

In post-production I started to realize that the recordings were a collection of instants that could be pasted in any order. I cannot explain the logic behind the editing. But it was not difficult. I realized that I had been editing while I was recording. I discovered that we plan things in the past, and later on, sometimes years later, we enact them without knowing, and this is why we think that events are destined. We find ourselves living inside intentions we laid down long ago.

As I began editing Stratigraphies I started to think of philosophers and writers who could refresh memories I didn’t have yet. I found moments of their thoughts on YouTube and recorded them and used this as a conceptual threading: Delueze, Cortazar, Francisco Varela, Beatriz Preciado. The work opens and closes with Borges. Stratigraphies is a video film using visual poetry bytes. My friend Deborah Roth suggested the title when she detected Deleuze in the work and thought than the video film was about geo-philosophy and becomings.

Mike: What about distribution? You’ve made a hundred videos, is it difficult to find places to show this work? Is it flowing?

Jorge: No it doesn’t flow smoothly. Fortunately I like doing what I’m doing but much of my work has never been shown. I make a lot and that becomes hard to distribute. I don’t spend too much time distributing, and I don’t play politics with people. Thirdly, there are not so many places to show video work anymore except for big festivals which requires you to mail discs and fill in forms. Perhaps it’s easier than distributing sculpture, but both are difficult to move. There’s too much being made, so it’s hard to show. Certain kinds of work are selected, works that are more officially accepted. The only way to distribute is to make objects, photographs for instance. I’m going back to photography in order to rescue a lot of work made in the past. When we went to Colombia recently we had a problem with the gallerists because they don’t know what to do with video. If you have photos they can sell them and that’s fine, but unless you’re an “accepted” video artist there’s no market. I don’t know who would buy videos except for museums and universities. It’s hard to find a home for these difficult, personal works, though they have an educational quality, often youth can relate to their experimental spirit.

I want to organize my own exhibitions. I’ve started a collective that self-curates. We came together because we like each other, and we like each other’s work. When we showed in Colombia people exclaimed, “Wow, who curated this?” In some respects, we’re against curators imposing their ideas. Why don’t I curate my own work? Rent a place, make posters and invite people. A lot of artists have to do that. I think that’s a good possibility because then you can make the work you want. There are more artists than spaces. I’ve put my work online for years now. Sometimes friends ask why I put the whole movie online, why not just a fragment, but creating excerpts is another job that doesn’t feel necessary. I hope people will see it and steal it and use it for their own purposes. Seriously. I would love to see something of mine reappear in a good tape. I’ve been able to live a nice life doing my work, and that’s what I care about. I’m not possessive about the work itself. Different artists require different protections. Somehow my work is public domain, open source.

Jorge

Nomination letter for Governor General Award, which he won in 2020 (June 2017)

Jorge Lozano has made more than 100 films and videos over the past four decades. A treasure of the international movie art scene, his restless visual inventions emerge from a period of super 8 activism and personal video interludes. His fiction films have been shown at Sundance and TIFF, though his preferred mode is formally inventive and visually witty shorts, documentary-based staging platforms where new identities and startling semiotic formations blend to produce wholly original forms of artist’s cinema.

His contributions to the field are multiple. He has managed to insert a racial discourse into the white canonical experimentalisms of North America and Europe. He has brought together radical forms with radical content – consistently finding new ways to map lineages of formal work on the signifier into the lives of subjects rarely seen in artist’s movies. He has refashioned the form of the political documentary, using expanded cinema and multiple-screen sculptural installations. He has fostered a thriving Latino community in Canada via international exchanges, screenings and workshops.

Jorge Lozano: “The portable video camera was developed by the American military so that it could be used as surveillance and recording equipment during the Vietnam War. In our hands it became a tool of resistance that helped transform our perceptions and aesthetic concerns. With the portapak we started to understand the mechanisms of bio-political technology used to control populations by regulating information. We had to be realistic, and demand the impossible.”

He has worked steadfastly to find new forms to disrupt and make newly visible the unmarked and invisible privileges of whiteness. Along the way he has experimented self-reflexively with forms in order to address power relations that shape the production, reception, and mediation of race representations.

For instance in Jorge’s early work The Three Sevens (1993), each section opens with an Anishinaabe elder speaking and singing. She is a reminder of the earliest keepers of the land, even as a roomful of immigrants vie to make a new home in Canada. But whose Canada will they arrive in? Reframing the question of displacement and power through an Indigenous lens (the artist himself is part Indigenous, part black, part white) the suite of stunningly photographed mini-portraits that follow show individuals fleeing violence and (re)forming communities. Questions about who belongs here and what accomodations are necessary run through the movie’s 21 1-minute scenes, as these new citizens mark out spaces between stable identities, haunted by photographs of disappeared relatives, inventing new lives. Because questions of nation and identity are posed from the margins, from the places without power via folks who fear deportation, the movie redraws and fragments the country’s map, delivering news from largely invisible populations. This place between places, between fixed and stable identities, is also a productive site of experimentalisms.

In Underscore/Subguión (2012) the artist presents a double-screen portrait of an unnamed political operative in Colombia who survives a harrowing series of assassination attempts. After meeting with the mayor he flees town, only to be shot on the road. From a stretcher in the hospital’s emergency room he calls for back-up, as armed pals eventually help spirit him out of the country. The artist blanks out every name and locational reference in order to protect his identity, these redactions appear as wounds and entry points, even as his image is doubled and resynthesized in an abstract cipher, as if he were giving voice to the many who were not lucky enough to dissent and live.

Jorge has steadily worked at the intersection of race, gender and class economics to produce new portraits of a global underclass, creating subversive documents of resistance and celebration. For instance Death Match (2010) offers a portrait of his cousin Alejandro whose kidney failure is connected to a series of economic disasters and failing health care in a series of dizzying linkages that intimately narrate the costs of globalized medicine. In movie after movie, the artist insists on a multiply-layered portrait that fragments and complicates the subject. In this instance Alejandro’s body becomes a contested political space whose survival depends on the state, and a spate of expensive health machines produced abroad. Each frame is an act of refocussing, from micro to macro and back again, from first-person survival to international pressures of colonialism and control.

In Land(e)scaping (2009) we meet Jessica Morales, a lesbian who is forced to leave El Salvador because of homophobia and violence. She is presented in a series of doubled frames filled with hills and highways, lines of flight and markings that score and divide the landscape. She is beaten in El Salvador, her property destroyed, and her life threatened by a member of the state military. The imperfect storm of sexuality, gender, militarism and state power once again resides in the body of an immigrant, someone who has become a refugee in her own country, and is then forced to flee. The movie is a way of granting “a voice to the voiceless,” redressing the power imbalances that she has experienced in her own life and the life of her country, which has drawn borders around gender and sexual preference as well as national identity.

In Toronto’s white-dominated art scene in the eighties identity politics was a keynote, and often rang out with essentialist understandings. Jorge has worked to complicate and reimagine those borders, even his earliest work offers complex identity-portraits that are multi-layered, criss-crossing race with sexual preferences, gender ambiguities, geographical heritages.

In Jorge’s work we are always asked to see how the border, the territory, is being re-marked. Sometimes this border arrives as a particular pressure used by the state to mark its citizens, sometimes the border designates gender or economic status. He has been one of the first media artists in Canada to take up trans gender representations, which he has complicated across decades of engagement. Samuel and Samantha (1992) remains a keynote. Toronto’s “gay ghetto/village” was clustered around Church and Wellesley, and many in the white (dominated) community discriminated against Latino gays. Trans folks and drag queens weren’t even considered gay. The policing of identities and the territories that those identities were permitted to occupy are eloquently narrated by Samuel, who transitions and becomes Samantha.

The movie premiered at the Images Festival in the Euclid Theatre. Across the road, the Pantera Rosa (Pink Panther) club had opened just a week earlier, providing a new home for queer Latinos and drag queens. After the packed screening everyone went across the road, and a venue that had been underground and almost exclusively Latino became known throughout the gay community. This venue was discovered via Jorge’s Samuel and Samantha. Later the same year, the movie was shown again at the same venue, this time during Inside Out, Toronto’s LGBT movie fest. The after-screening party was held at El Convento Rico, a few blocks west of the theatre, and this party put Rico on the city’s gay map. It quickly became a home for drag queen beauty contests and late night queer celebrations. East of Pantera Rosa, the owner of El Convento Rico opened Tacones (High Heels), and because of these three clubs this strip of College Street was redubbed “the pink triangle.” These clubs dislocated and relocated Toronto’s white gay village, now there was a gay Latin satellite. Jorge’s aesthetic reformations have always been tied to political formations, as he works to bring unseen faces to the screen, and insist on multiple identity readings. For his sterling contributions to community/neighbourhood building, Jorge received awards from Hola, the gay Latino association, recognizing and expressing appreciation for his accomplishments.

Jorge is one of earliest and most consistent chroniclers of gay Latino life in Toronto during the past decades, showing up at marches, demonstrations, rallies and nightclubs. His ongoing community reports appear in many movies and installations, from the billboard remix of In the Body of Knowledge (1981), the collage-essay Does the Knife Cry When It Enters the Skin? (1984), the Nicaraguan revolutionary ode Letter from Fatima (1984), community soapbox What’s Going On? (1990), anti-identity audio-visual graffiti proclamation Samplings (1990), the queer narrativizes of Brief Chronicles of Glia and Luna (1992), the arch-feminist Pacquita La Del Barrio (2000), poet bio-short Pedro Pietri: Purto Rican Obituary (2000), the performative lesbian idyll of In Deep Skin (2004), the irreverent trans portrait Lola’s Art (2009), and Situations (2012), a triple-screen condensation of public resistances. Unlike some of the more strident work of his peers during the same period, Jorge’s movies are both aesthetically sublime and politically sensitive, a major bulwark and support for a community that continues to be politically active.

Not content to produce work, he co-started the aluCine Toronto Latin film and media arts festival in 1995. Canada’s longest-running Latin film festival celebrated its twentieth anniversary a couple of years ago with a massive Jorge retrospective, as it continues to provide a two-way portal between Latin American artists and Canadian residents. When it was necessary in the earliest years Jorge ran it out of his living room, and arranged screenings and tours throughout Asia and Europe, showering artists with the customs of his generosity.

He has also helped innumerable artists-of-colour to create movies, acting as camera operator, musician, sound recordist, editor, producer. His small cache of low-fi gear has been distributed widely across the city, and his name appears again and again in the credits of movies made by others, as his DIY spirit inspires and animates those around him. The list of artists he has helped along the way reads like a who’s who of Canadian media artists of colour.

For the past two decades he has organized youth workshops, both in Canada and across South America. Typically working with homeless kids, economic precariots struggling with racism and criminal records, he has developed new forms of pedagogy that empower youth through self-representation. Refusing traditional hierarchies of teacher and student, he has helped hundreds of first-time makers make personal, socially conscious works, many of which have gone on to great acclaim in festivals round the world.

In the past dozen years Jorge has divided his time between his former home of Colombia and Toronto, which has lent his work a renewed political focus along with a keen aesthetic wit. As TIFF programmer Chris Kennedy notes: “The last decade has been extremely prolific for Lozano: half of the nearly 100 works in his videography were made since 2005, and he has expanded from single-channel work to installation, most impressively with the eight-screen MOVING STILL_still life, which premiered at the Ryerson Image Centre in late 2015. Part of this explosion of work derives from Lozano reconnecting with his Colombian homeland through frequent travel to his birthplace to lead youth media workshops, which has stoked his desire to tell stories from the impoverished areas of a country still suffering through a long-running civil war.”

It is difficult to keep track of this nomadic voyager, no sooner have I digested one of his luxurious outpourings then he invites me over to watch another. He is forever translating his thoughts and encounters into media moments, deeply concerned with the art of asking questions. Why this gender? Why this desire, this neighbourhood, this poverty? The artist’s commitment to experimentalism is animated by the necessity of these questions, which are forever opening, like the artist’s heart.