I am sitting in La Bodega, a Tapas bar whose dim lighting mercifully disguises the decline of decor and customer alike. Everyone around the two generous oval tables has just watched a night of Chris Welsby movies next door at the Cinematheque. Chris teaches at one of the two universities in town, so there’s a bit of a home-brewed, local hero feeling. This is offset by the fact that he speaks with an irresistibly plummy English accent, and that despite his movie star looks his work is “about” landscape, often very English landscapes.

As someone dedicated to filling the coffers of multinational tobacco companies I have two or three before joining the comrades, which means that drinks are already down and tortured seating accommodations made before a couple of unlikely suspects budge enough to fit another chair. I wind up between two strangers, not unusual on nights like this. These kinds of movies really raise the geek content of a room, no matter how many show up it doesn’t gather into a crowd, our evenings together never quite manage to escape the feeling of deep hobbyists in someone’s basement. Where are we, the underground? Sitting together in the theatre is discouraged, it is already a sign that you’re not ‘serious.’ Nobody walks through the door by accident.

We might be comic book freaks or the kind of people who spend their weekends dressed down in medieval tunics but instead we enjoy watching movies about the way light changes along a river bank. Like everyone else here, I like to keep pretending I’m still alone in my room, this helps reduce the noise of social awkwardness. For a moment I climb up over this to introduce myself to young Clay, one of the suitably expressionless people sitting beside me at the bar. Clay is from Frankfurt as it turns out, a city which has not been unkind to people making movies about the way light changes along river banks. It hosts some kind of art academy and sure enough, that’s what Clay used to call home. What schools like this are trying to teach is the rarefied attention that permits audience and maker alike to see anything like a “movie” in what artists get up to. I remember hauling a 16mm projector from the library and bringing it home where a couple of friends sat and watched an image about the size of an oversized paperback flickering away on my bedroom wall. We drank beer and sat entranced as a camera zoom slowly picked its way across a loft for nearly an hour. Occasionally people would walk in and out of the movie room, carrying away furniture, or falling on the floor. Eventually a photograph on the far wall filled the frame. We were thrilled, but it’s not everyone’s idea of a hot Friday night.

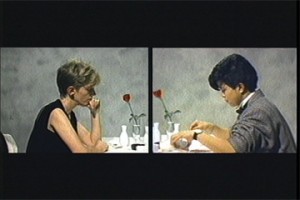

Young Clay speaks with a sturdy self assurance I will never manage, the jam flows out of him so easily that it’s hard to concentrate on a word he says. Through the static I learn that there is some kind of treaty signed between “our” countries (Canada has become, in his presence, “mine,” just as Germany belongs to him) which has allowed him to get a year long work visa with a minimum of paperwork. Kein problem! He tells me in perfect English, “You know, there are many myths about Canada and most of them are not true at all.” Oh? “For example, we are always told that Canada is a multicultural country, but look…” he says, gesturing across the table, where a collection of very white people are throwing beer down their faces. Our faces. I feel a surge of nationalist chauvinism rise up and though I have no beer of my own to calm me, I want to pour enough fructose sweetened lager down my newly unwanted guest’s throat until he repeats my version of the truth. I want to impress him with the amount of Chinese food I’ve eaten since moving here, or the number of times I’ve grocery shopped in Japan town. I want most of all to floor him with a long list of avant movie makers that aren’t white and there are a few that leap to view but they are not the usual. The heroes on the altar, the writers of books, the slayers of Hollywood, they generally come in one colour. They were occasionally queer or drug addicts or poor, sometimes all at the same time, but the unsilent majority were white. There was Teijo Ito for instance but he only made the music. There was Taka Iimura, the one who made “counting” films with lengths of black and white leader. Or Yoko Ono but she was a pop star. And there was Nam June Paik of course, the first son of video art who raced out to buy a camera the day they arrived at the Sony warehouse. Because of the pope’s visit he was stuck in a traffic jam on the way back, and with typical can-do Fluxus attitude he unpacked his new purchase, aimed it out the window and showed the results later that night at the Cafe a Go Go. This was the beginning of video art, but even though it lay in the hands of the Korean prankster, most who followed him into the world of low resolution were white.

Clay was still staring at me with the same determined expressionless look on his face. Well? Was this country just as racist as his beloved Frankfurt? While his grandfather, or friends of his grandfather, were busy rounding up Jews, Canadians were tracking down citizens who happened to be of Japanese descent and herding them into internment camps. I remember speaking with Midi, a Japanese-Canadian film artist who has kept the avant torch burning with her own light. She was turning to drama, she announced too long ago to remember, because as a woman who was Japanese, not to mention queer, she was already far enough out on the margins. She didn’t need to say the rest, the implication was clear. The only folks who could afford to occupy these narrow reaches were white and male. It was a privilege to be so damned marginal, to set sights so small, and this privilege, like most others, was reserved for those who never figured white as a colour at all.

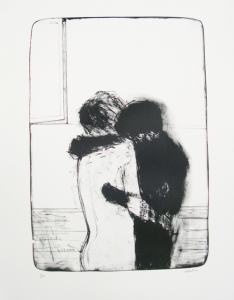

Like everyone else, I imagined myself alone and misunderstood, oppressed by unseen forces (like gravity and the state) I was never quite able to put my finger on. And the movies I loved, these small, no-budget testaments, constituted the thin edge of resistance which would one day bring down the shibboleth of corporate media. When David Rimmer showed us his Canadian Pacific movies for instance, eleven minute looks (silent of course!) out a pair of Gastown windows overseeing the harbour (there are no people, only weather, water, mountains and trains) I imagined in the raw contemplation they required a population which would become more ethical and gracious, kinder and more patient. We would open to strangers the way David’s eyes opened (or became) the windows of his apartment, no longer seeking distraction but each other, content to keep vigil until welcome occurred on all sides, attuned always to the smallest lapse of pleasure in each other. Our vigil, our hopes, would be steadfast, and we would share them, each of us a projector, in glowing flickers of kindness.

That David’s work could be made so inexpensively, against the media current, making a virtue of its smallness somehow, refusing awards and the business of show, refusing the very idea of a marketplace-wasn’t all this the beginning of the end of capitalism? Wouldn’t the empire give way beneath our careful attentions?

Well no, not at all, but I only figured that later. And worse, this work was being made for the most part by white people, and if there weren’t a whole lot of folks gathered to notice, the very powerless, ineffectual consequence of the practice ensured that avant apartheid wouldn’t be making headlines anytime soon. But this was a place that traded in pictures above all, and the white communions of alternative cinemas presented a picture that was only now (what took so long?) coming into focus for me.

Clay’s breezy wave across the bar (“…but look…”) hurt because this city was not exactly a bastion of white power. Large swaths of the toniest neighborhoods belonged to the Hong Kong charge and much of the city’s centre was stuffed to bursting with people from every country on the planet. Only they didn’t come to these movies, they weren’t interested in my interests, they weren’t part of “my” Vancouver. And why should they be? How many Vancouvers could there be exactly? I haven’t read the population sign lately but that might afford a clue.

Clay and I stared mutely at each for a little while without either of us getting too worked up about it. Lapses in normal social niceties were pretty normal around here. In between stares and a beer which appeared as the terminal point in our non-conversation, I filled my word balloon with questions I couldn’t say out loud yet. But if I could have told the story it might have gone like this: was I celebrating, in those long hours of contemplating water dripping into sinks, torn up emulsions or drapes blowing in the breeze, a more rigorous and rarefied version of my whiteness?

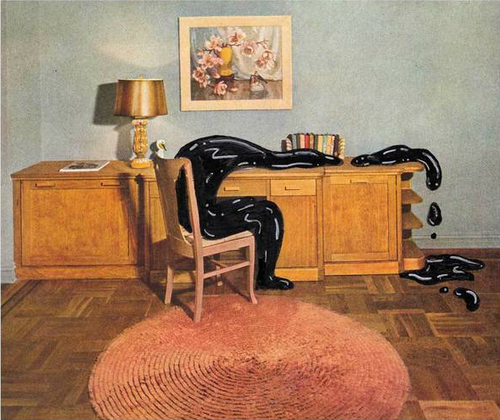

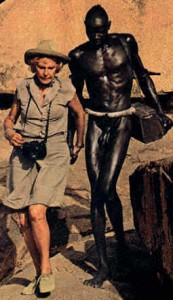

I wondered about the movies we’d seen that night, if I had come with my friend Carolynne, who is Chinese, would she have looked at the crowd like she did when we saw Antony and the Johnsons and assure me, “This is melancholy white people’s music.” Chris Welsby, who was charmingly holding forth at the inconceivable centre of the other table, made movies where people often didn’t appear at all. One of them, for instance, takes a trip up a river. Could someone call this movie racist? In her review of Riefenstahl’s book of photos about the Nuba, an African tribe, Susan Sontag articulated those qualities which comprised a fascist aesthetic. It didn’t require armbands or the Fuhrer or even a party as it turns out, there were principles that could be applied to far flung situations, an eye schooled in the discipline. Sontag’s closing line is so apt I can’t resist quoting it here: “The colour is black, the material is leather, the seduction is beauty, the justification is honesty, the aim is ecstasy, the fantasy is death.”

Perhaps, after all, it would be possible to sketch out, even in a preliminary way, what might constitute ‘whiteness’ in the small movies I enjoyed, not to shrink them all down to that term, but to try to find my way out of the snowstorm, to see white again as a colour. What does a white (artist’s) movie look like?

(If this missive had been run up by someone with a more rigorous bent (if all those movies had taken hold in a deeper way) this essay would contain only the title, followed by a few empty pages, leaving the reader to consider the white blankness of it all.)

White Light

Fringe movies were cheap even compared to the leanest of no-budget dramas, but when they were stacked up against any of the more traditional fine arts they looked like a rich person’s game, and worse, required a modicum of managerial skills from their makers. Feature filmmakers are manager kings, they are deal makers and traffic cops, the amount of creative/idea time is very small, while the amount of managing other people’s time is very large. When people ask me, with decreasing frequency these days, “Why don’t you make a feature?” what they are really wondering is why don’t I become a full time manager with a staff and a producer and file drawers full of contracts, applications and deal memos. Little wonder that it is these folks, along with their poreless front men and women (the stars, the friendly face of all that money) who are so cherished and celebrated.

It probably comes as little surprise that most of the Canadian film industry that breathes the thin air at the top is white, and its nominal and largely ignored opposition has also been predominantly white. Even Chris Welsby had to buy his own cranked by hand camera, and eat the rising costs of exposing 16mm film. The lab processing and colour timing, the sound mix, the machines used for editing-all of this comprises a technology that has been dominated, at least in North America, by white people. White managers. Not that it’s been exclusive by any means—no one’s forgetting the fabulous Paul Wong or Fumiko Kiyooka and there are many more who could be mentioned. But if you line up all the suspects for a head count the numbers speak for themselves.

The fringe media world has been largely content to gaze upon itself, it’s not unusual to be “expected,” as a local media artist, to come out and support the work of visiting artists. Who else would be interested? The secret codes which flash away at these screenings can be difficult to follow for the uninitiated. Not to mention pleasure. It’s not even a question of deciding, “No, I don’t want to see that.” It’s a question of: I don’t know what that is, I’ve never heard about it, I wouldn’t even know where to look for it. It might be happening next door, I could be staring at it with both eyes wide shut but it still only reads like noise. One of the great failures of the fringe has been an absence of marketing (do we (the artists) have to do EVERYthing?), and this failure is a default posture that has produced an insular, largely white community.

Fifteen years ago, around the time of Chris’s screening, the most dreaded audience question was, “What is the movie about?” The answer was usually something terse like, “Memory,” or: “The act of seeing.” While the smarted up kids of colour were making docs around specific situations, here was a world of universal themes and universal language. This sometimes required a universal attention span. Shots could be held for a long time, this was a sign of ‘rigour,’ the most coveted of all word trophies. Yes, it’s rigorous. Paul Winkler’s thirty minute movie about patterns in wood called Bark Rind was ‘rigorous.’ Paul Sharit’s half hour flicker movie of epileptic seizures called Epileptic Seizure Comparison was way fucking rigorous. No doubt about it. These white movies might veer towards the abstract, there was a mistrust of language, which had something to do with a refusal of the social. Talking wasn’t pure cinema, nevermind fellow white guy Godard, this was an optical avant garde, if you can’t show it then forget about it. And all this work was the issue of solitary makers, if you could make your own emulsion, build the projector and screen, that would be even better. But at the very least you had to shoot it all, cut it up and compose the sound (or better: leave it silent! That was rigourous too, sound was for wimps and panderers.) This work was made as if in answer to the question: but what do you DO alone all those hours? This work was made to be alone, to stay alone, to show others how to stand alone. How did so much solitary become solidarity?

Perhaps all this work on the rhetoric of the image, these relentless personal interrogations, would provide a useful palette for those who would come after who would have something to say.

In those days I was sure that people would grow sick of the same motion picture formulas and simply tune out. But living in Vancouver disabused me of this notion too. I had never lived in a place where culture mattered less. If every speck of culture was gathered up and tossed off the First Narrows Bridge no one would notice. But perhaps the problem lay in the micro scene itself, those self enclosed envelopes which never managed to open quite far enough to embrace another kind of Vancouver. Are you talking to me? To me? As a white male, everywhere I look I see myself reflected, in store after story the rock stars are singing my song, making sure that nothing comes between me and my white designer. I turned at last to Clay, who hasn’t managed another word, though he’s taken a healthy cut out of three large glasses of very bad draft. “So what’s it like in Frankfurt?” I ask him, and by the way he smiles I can tell it’s the question he’s been waiting for all along. I’ll be your mirror, I’ll listen to your song. And you’ll listen to mine. Good old white buddy old friend. Clay talks and I can’t remember a thing he says and he doesn’t care and I don’t care either. It’s us now, it’s us altogether in the same room. Cheers.

Afterimage 1

The pentagon has done their part to come up with a solution for all this, another reminder that “avant-garde” is a term coined by the military. They were responsible for creating the internet which has done so much to dissolve and transform local space. Even the most rarefied of anti-products can be found there (not everything yet but these are still early days), no longer does someone have to show up with their 16mm movies under one arm and the stump speech under the other. Access is no longer restricted to city dwellers or barred by curators. Not only is the internet an (admittedly unpaid) distribution portal, but footage can be accessed, downloaded and replotted into one’s own movie at little cost. And the advent of digital video has led a downward price spiral which has allowed explosions of video art in Korea, China and India, amongst other places. As this work hits the screen, how long will it be before their hyphenated diaspora take up the chase, producing reaction shots from their embedded places in the centre of white power? Here is what’s already begun: globalization is delivering the images that the unplotted exclusions of an earlier avant scene has left behind. How can you leave out what isn’t there? How can you refuse negative space? But where once there was a handful of makers, now festivals are typically looking at thousands of small, personal statements, most of them penny dreadful, but at last from many corners of the world. As the momentum of digital production creates a dispersed geography of makers, exhibition portals have become testing grounds for this burgeoning production. There are, for instance, micro festivals emerging at rapid speed which offer ever more specialized fare, often based on where the work has been made. Thirty years ago there were National Geographic magazines. Today, movie festivals offer glimpses and testimony from abroad. And there is, of course, at the same time, a proliferating abundance of white makers new and old, looking more marginal than ever in the face of digital television’s multitude of channels. Should all this be consigned to the shelves of “distributors” which are busy hawking wares almost no one is interested in? No worries, it already is. How much room to make, then, in festivals or microcinemas which have their own stakes laid down in certain artist’s production, favourite sons and daughters, arenas of white pleasure which have served so reliably in the past. Is all this to be left aside so that the new thing can be granted its moment at the centre of a centreless microverse? Shall we reserve a place in the basement for them too? Or perhaps they can skip these trials of attrition and move smoothly into the art world, where exhibits of Chinese video (to name only one) has been admitted onto some big time stages.

This much is for sure: work by people of colour will continue to be made which will be good and bad and middling, its very existence provoking a pressure for visibility. Its exhibition will help accumulate audiences and response. Most of this work will be dramas or docs, but some, not much perhaps, but some at least, will fit into that uneasy, neither-this-nor-that category of “video art.” Though no one is wishing for it exactly, hoping that new skids of work will arrive bearing the hyper marginal status of video art would be like hoping a child is born ugly. Nonetheless. Already there are fissures and openings in the land of white cubes which have been darkened to permit projections from near and far. Especially far. But how white gatekeepers will respond to present events remains to be seen, there have been a smattering of “special programs,” but the guts of celebrations like Visions from the Avant Garde in New York, or the fringe delegations from large festivals in Rotterdam and London, Toronto and Berlin, the avant safe houses in San Francisco and Vienna, all these have yet to register the seismic shift which has already occurred. Certainly the search for the new is persistent, but will the values that lead the search, the roots of white aesthetics (what makes a good work good) shift enough to permit the entrance of work from elsewhere?

Globalization will put an end to the ghetto, or at the very least transform it beyond recognition, by the simple fact that people are making work, which in turn requires places to show. If the small rooms of the avant scene aren’t involved, the excluded will simply rush on past towards visibility. If we choose not to show this new work, or look at it, it will signal a failure to learn and adapt, to engage in the most useful arguments around representation: how the power of the image is motivated by power, how to see the Other.

Afterimage 2

A week later I am standing in the living room of Dr. Ernest To, a ninety something grandfather of a friend who made his fortune years ago X-raying Hong Kongers for signs of TB. Looking out at his neighbour walking a pair of well heeled Pomeranians he snorts at me, “Chinese no good. Chinese no good for this neighborhood.” Ernest, of course, is Chinese. He would never make an avant movie, though he was charmed enough to be able to shoot film on some of his many trips abroad. Mostly they show buildings and cityscapes. Tell you what, they wouldn’t be entirely out of place at a fringe movie showhouse, but it would never enter his mind to do it. He can’t see his own footage that way, he had managed to uncover through his looking hobby some of the seeing that was commonplace in the small halls where artists’s attention were grown. But lacking the understanding of genre his camera wieldings remained private, gathering dust in the closet. Because of his advancing age, he is a man increasingly used to limitation, so the confines of genre, even in its most rarefied form as artist’s film and video, may yet appeal to him. What white seed lay inside him to urge such a remark against his neighbour I wonder, and what other seeds had also been laid, even after a night of English landscape movies, which might one day bloom into a worthy, even useful resistance?