Inner Critic

Last week we looked at a cornerstone, a foundation of the practice of ethics. We called it non-violence or non-harming. And we tried to find this place within ourselves, in the relationship we have to ourselves. Are we expressing non-harming in the relationship we have to ourselves?

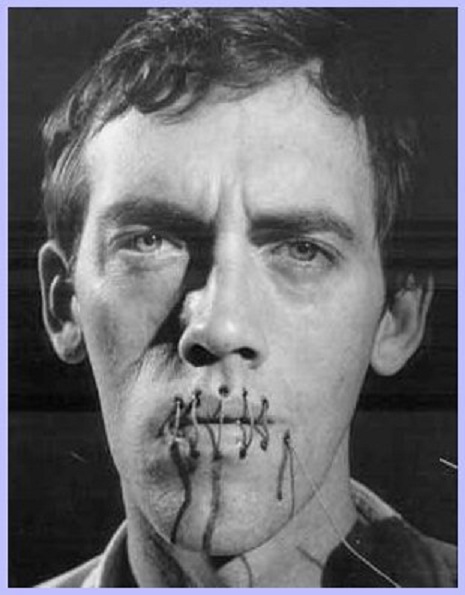

When we examined this relationship we found: the inner critic. Oh, that wasn’t a happy moment. A very difficult person to practice with, the inner critic. It took courage to do that, it meant that every person in this room had the strength to face one of the most difficult things you’re ever going to face, which is the way we produce darkness inside ourselves. We discovered that actually, our experience might appear varied and fragmented and rich and unexpected, but what we see filling our mirror is not all that, but instead: the inner critic. Over and over. They are a very sad and angry person, or a sad and angry wall, or a sad and angry mist, who seem to have only one obsessive preoccupation: telling us that we will never ever be good enough.

It’s as if we live in a world filled with bursting colours, with bursting feelings, only we prefer black and white.

The scenario was: you meet up with your inner critic at a party. You approach them and have a conversation. What do they look like? What is your conversation like? For some folks, that I couldn’t help overhearing, the inner critic seemed to do all the talking. As if there was no way to have a flow, an exchange, a dialogue. Perhaps you have another relationship that runs like this in your life, whenever you get together they just talk talk talk. Even though they might appear powerful, and create beautiful sentences (because they’ve had so much practice) what they’re really expressing is need, a terrible neediness for attention. You often see this in powerful people, like politicians, or leaders of groups, people who sit in this spot and talk, many of us are driven by this sense of not being enough. We’re hungry ghosts, no matter how much attention you give me, it’s never enough.

My favourite description of the inner critic: he lives in a jazz bar, listening to the changes. The friend who tells me this confesses: I don’t even like jazz, but I feel as if I should. The jazz hipster/inner critic doesn’t scream out worthlessness, preferring instead to drop snide remarks.

To each their own punishment, for each their own litany, repeated, consecrated, returned to, as if in worship, or compulsively, like the trauma of a repeating wound.

You go to the party, you see the inner critic lounging there at the drinks table, but when you approach them you can’t say a word. All we can do is listen. Can anyone remember a time in your life, when you didn’t have any power, when all you could do was listen while someone much more powerful than you, did all the talking? Oh, hi mom and dad. Fancy meeting you here.

Pride

Here is David Wojnarowicz (Wonna-row-vich) (NY artist, died of AIDS) describing kids in the schoolyard calling each other faggot. “The sound of it (the sound of that word) resonated in my shoes, that instant solitude, that breathing glass wall no one else saw.” The glass wall, the separating boundary, the deep sense of shame. He is rendered speechless. The reason we need a pride parade, and especially such a big pride parade in this city, is because there are so many unprideful moments, when the law is going to punish you for who you love, and the law could be the seven year old in the playground, or the landlord who won’t let the two of you rent the apartment. It’s difficult not to absorb the voice of the culture, and turn it into your voice. And these voices of racism and homophobia, are also our voices, part of the shame of being a man who has slept with other men, is my own homophobia. And this ism and phobia and separation is driven by fear.

Cultural grooves

The inner critic and the outer critic is fuelled by the fears that live in our culture. In many fundamental ways, the inner critic, your inner critic, is not personal. Does that seem strange to say? It feels so personal, but it’s an energy flowing through the culture, and then it flows through all of us. It’s the energy that says: the city of Rome has just elected a woman as a mayor for the first time. For all these centuries, was a woman not good enough to be the mayor of Rome? Isn’t that what the dominant habit pattern is telling us? It can be hard not to inhale that, not to let it become part of you, and then, if a woman is somehow lesser than a man, because all the mayors of Rome are men, and all the presidents, and all the leaders of the university, and then you get to rooms like this one, then it can become hard to talk, if you’re a woman, to speak up, to have a voice, as a woman. Even in traditions like Zen, because it has a centuries-old history where men do almost all the talking. And those men are giving me the power to speak right now. I’m standing on their shoulders, I’m part of that groove right now. This is what is known as privilege. I’m exercising my privilege. The whole culture is designed to create hierarchies and separations, glass walls, between what is good and normal and acceptable (but we’ve always elected a man as the mayor of Rome), and what is not good, what is disgusting, what is a faggot and unwanted.

Tell me: was it strange to hear from someone else, and then from so many others around the room, that they also had an experience of being treated badly by their inner critic, that their experience might have been similar to your own? That this intimate life partner, your true husband, your double, your wife, yourself – tell me, was it strange to hear out of the mouths of others the words and attitudes that belonged to your very own cherished inner critic? Does it seem strange that we live in a culture that produces this general feeling of inadequacy? And: what kind of culture could we cultivate that might produce something else?

How can we engage in the practice of non-harming, if we spend so much of our time, if we are caught up in the habit, of harming ourselves? How could we help but throwing some of our judgementalisms, the way we judge ourselves, the way we like to compare ourselves to, you know, philosophers who look like supermodels – how can we help but feel bad about failing to live up to those impossible ideals, and then lay some of that disappointment and darkness on the people who are around us, and then, because we’re practicing mindfulness, we start noticing that we’re doing that to other people, and then we can beat ourselves up about that too.

We held this question in the room altogether, we asked: why do we seem so enchanted, so mesmerized by this inner critic, when they’re the most boring person in the room, always saying the same thing, jumping to the same conclusion. Paul said that it was about fear. That we fear meeting this moment as it is, or having a conversation where we don’t know what’s going to happen, or opening our face. Instead of allowing this moment to flow through us we reach for our inner critic. How should I feel inner critic? You should be afraid. Oh, thanks. You should feel ashamed, you haven’t done enough. Oh thank you, thank you. Yes sure, the inner critic gives us a bad feeling, but it’s the same bad feeling, it’s a reliable bad feeling.

So there’s a deep relationship between the inner critic and fear. The inner critic is born out of fear, it is the voice of fear itself. The inner critic shows us what the world looks like, when we see it through fear.

Calling

One other note. How often does the inner critic take shape as a voice? As if it were a calling, as the Christians, the Muslims, the Jews used to name it? My life’s vocation, my one true path. It signals some fundamental separation between the sensations of this moment, the life of this body here and now, and the escape hatch of descriptors, the abstractions of language. How can I feel this moment if I’m so busy telling myself the story of how I fit into it? Does it seem strange that the only way I seem to be able to write/speak myself into the story is by playing the emotional bottom? Always casting myself in the same part. The flight from sensation, from these unwanted and uncontrolled feelings, the live wire of this body which is forever connecting to the sun, air, spit, carbon, colour, with everything really, all this leaves me when the storytelling machine starts up again, and then I’m lost again in the old dream, the oldest dream of separation. Perhaps there is an ongoing practice, fuelled by the great fear bodies of mass media, that keeps us behind the glass wall, that defines us, that gives us definition, an outline we can call our own, filled with abject fantasies of not-enoughness learned in the early cuts of development. There is another practice however, which is not quite so quick to convert experience into language, or to leave the body behind, or to provide worshipful attentions to the inner critic. Some call it zen.

Nothing Holy About It by Tim Burkett

(words taken from Tim’s incredible book Nothing Holy About It)

1. To see the world just as it is, you must relinquish your distorting ideas, views, and concepts. Most of us prefer to limit our experience, to sit in the Chatterbox Café of our mind, where our inner narrator mediates for us. Rather than interacting with the world directly, we interact with our thoughts about the world. In the Chatterbox Café we experience our life as a story narrated by our inner critic.

2. Zen is about seeing the nature of this mediator and gradually letting it go. In meditation, we learn to open up to our immediate thoughts, sensations, and emotions and see how we react to them.

3. The problem comes when we don’t want to feel our anger, jealousy, arousal, sadness, so we move away from it. When we try to escape our own heart, we close down, and our life becomes isolated and lonely.

4. As we make friends with the hindrances ingrained in our personality, we will see what triggers them and how they affect our behavior.

5. In Buddhist thought, we can’t be ripped out of the fabric of the universe because we are the fabric. At the very ground of our being we are pure pristine awareness. This awareness is our basic goodness or Buddha nature.

6. With practice we begin to empty out, becoming more transparent to the world as it actually is, rather than how we think it is or want it to be.

7. Emptiness refers to a mind that is open and receptive to whatever is happening.

8. When tragedy strikes it’s natural to want to close our heart to protect it. But transformation happens every time we’re able to stay open.

Ticket

What I hear in these sentences is that there is a big world filled with sounds and conversations and sudden jolts and boring endless waiting for the bus moments when you wonder: when will this ever end? But it’s as if there’s something between me and the world. Do you hear that? It’s as if we keep pushing our inner critic through the door of the room first, “Go ahead, you first, see what it’s like in there”, so they take a peak and then turn back to you and say: “Everyone here is better than you are,” hey, then it’s safe to go in right? Does it seem weird that everyone else in the room has gone through a version of the same schtick? The rule says that before stepping into the room you have to get a ticket from the inner critic that says: you’re not enough, you’re the dumbest person here. When you walk into the room oh look, everyone has a ticket. Everyone has a ticket as if we all went to the same ticket booth. It’s a strange game we seem to be playing, which is designed so that everyone will lose, and we’ll all lose in a similar way.

Warrior

In the Tibetan tradition of Buddhism, they use a word for people who are on the path of the dharma. The word is: warrior. They call people who are on the eightfold path: warriors. It’s not because Buddhists in Tibet carry submachine guns to protect them from the Chinese government who has stolen their country. Instead it refers to fear. A warrior, in this tradition, is someone who is willing to be who they are. A warrior means being yourself. Sadness is arising. The warrior says yes. Boredom is arising. The warrior doesn’t say: I better watch more Youtube videos, the warrior says: ok, boredom is arising. A warrior means that you don’t have to hide from your feelings, you don’t have to send your inner critic into the room first.

How do we become a warrior? How do we practice non-harming? By working with our fear. By becoming a friend, to our fear. By leaning in to our fears.

Yoga

The word yoga comes from a Sanskrit word “yuj” meaning to bring together, to connect, to join. It’s a word that describes what happens “naturally” when we can let go of our fear. When we can meet, when we can join, when we can connect, with this floor that’s so swollen in the heat, when we can meet another person’s face without any judgment, without any good or bad, when we can meet someone else’s face without having to decide, we’re just here together, in the same moment. We’re not tuning our inner critic in on the radio – don’t worry, don’t worry, they’ll still be there later. But the practice of yoga is the practice of this moment, it’s what is actually happening, right now.

Perhaps we could say that the practice of yoga, the practice of non-harming, might have something to do with our relationship to fear. That practicing non-harming, that becoming non-harming, might mean holding our fear in a different way.

So I was wondering how we might get in touch with our fear without having to jump out the window or dangle each other off the roof. I was wondering if we could locate our sensations in the body, in the frame of this body-mind. Where does fear live in your body? Can we make an examination together, can we proceed with curiosity?

Sensations

What is a sensation? It’s not jealousy, though jealousy is something we can feel in the body. The sensation of stepping into the sunlight produces heat, the atoms are moving faster, wetness, dampness, tightness, a sinking feeling, a warm tingling in my chest, a throbbing in my fingers. These are sensations. Can we awake to the world of sensations as we begin to reimagine our relationship to fear?

Exercise

Let’s do this simple exercise, it’s designed to plunge us back into the frame of this body/mind, to put us in touch with our sensations, instead of our ideas. Could half the people in the room come to this wall, and half gather at the other wall. (Hand out blindfolds) The object is to walk across the room, and touch the wall on the other side. The object is to stay in your body, and note the sensations you feel, not the ideas you have, but the sensations that arise as you make your trip. Can you stay with the sensations and notice how they arise and pass, arise and fall away.

Then five minute partner exercise – what bodily sensations did you experience? Did you ever feel fear? What did fear feel like? What part of your body does fear reside in?

Fear

(Tim Burkett quotes)

1. The fear body can manifest in three common ways. The first is withdrawal. When I was labeled as gifted at three years old I began to contract around the idea of being gifted. As adults we contract around our strongly held opinions. We can try to force our stories onto others.

2. The second manifestation of the fear body is lashing out, either in anger or through competition, always needing to be better.

3. The third manifestation of the fear body is going numb. We numb out through alcohol, drugs, sex, gambling, TV, workaholics.

4. In meditation it’s ok to feel all of your intense emotions, feel the sensations, even of murderous rage, breathe into it, and allow it to pass on without turning it into stories. Stay with sensations, with the direct experience of our emotions, then we don’t need to act on them. We transform their negative energy into positive, constructive energy. But first we have to become an expert on our fear. Not fear in general but our own fear. Fear is not something remote to be studied, it’s immediate, if we can experience fear directly, in a calm and kind way, it loses its power.

5. From birth to death we are being imprinted by our environment. Fear is unavoidable, it is imprinted on us by family and culture. RD Laing: The range of what we think and do is limited by what we fail to notice.

6. It is contrary to the nature of the fear body to extend itself. It can only contract, making us feel tight and small. We react to the fear body by clinging and holding on to things. We hold on to time, money and status. We have no time to spare, no money to donate, we rarely do what we really want. When the fear body is present, the first thing that goes is generosity, because sticking and clinging are the opposite of generosity.

7. When a hindrance (sensual desire, ill will, sloth, worry, doubt) arises, it’s usually covering some basic fundamental fear. We hold on to it because it’s preferable to fear. But clinging to a hindrance causes us to lose our centre. We become unsteady, as if were skating on ice. In a sense, we are skating on ice because the hindrance creates an icy sheath over our fear and protects us from it. We don’t want to break through. But we are separated from our life, our vitality. Training with the hindrances is about breaking through the ice and meeting what it is that isolates us.

8. When I was a student at Stanford, Suzuki Roshi was invited there to speak. I sat next to him in the first row as he waited to be introduced. Suddenly, he took my hand and squeezed it. “I’m scared,” he uttered. But when it came time for his talk, he was calm and totally available. He did not fear the sensation of being scared. He didn’t contract around it or cling to it. When it arose, he acknowledged it and felt it fully, and it passed on through. He freed up the energy of fear, so it could be transformed. He met fear with kindness, and then he was free to give himself wholeheartedly to his activity.’

9. What if I completely let go of the fear body and were released from the gloomy future it predicted? What would I want my life to be about? As we ask these questions and feel the resistance they arouse, we begin to recognize how hypnotized we are by the fear body. Once we learn to recognize how fear drives our choices, we can choose differently. Deep questioning can help us to break through the hypnotic spell fear casts. We can practice deep questioning the same way we practice returning to our breath in meditation. When we bring our awareness back to the question over and over, the question sinks deeper into our skin. Deep questioning extends us beyond the fear body. Just holding the question is enough, because it is the question – not the answer – that opens us up. Answers can be sticking places. What is the most important thing to do?

Exercise

Let’s go round the circle and one person will ask a question, and then the next person will answer it. And when you’re asking the question, and when you’re answering the question, you’re part of the same practice, the practice of working with your fear. The practice of working with your inner critic. Let’s ask a question to the fear body – to the place in your body where you feel fear.

Chogyam Trungpa: “Sometimes people find that being tender and raw is threatening and exhausting. Openness seems demanding and energy consuming, so they prefer to cover up their tender heart. Vulnerability can sometimes make you nervous. It is uncomfortable to feel so real, so you want to numb yourself. You look for some kind of anaesthetic, anything that will provide you with entertainment. Then you can forget the discomfort of reality. People don’t want to live with their basic rawness for even fifteen minutes.”

Their basic rawnesss. Their openness and vulnerability. Trungpa says that we are fighting a war inside us, against ourselves. It’s an ongoing civil war. And then we bring that war outside, and that is the war against the Palestinians who live in the most terrible conditions in Gaza, and it is the war against the Syrian people, it is the war against the Kurds in Turkey. Trungpa says that you have to heal your war, you have to look after your own ceasefire, you have to attend to the fears that belong to your war, and then also to the fears and wars of the outside world. And then inside, and then outside, because the inside is part of the outside. We can work for peace by facing our fears. Trungpa: “…meditation practice is regarded as a good and and in fact excellent way to overcome warfare in the world: our own warfare as well as greater warfare.”

Here is one of Buddha’s students: “Before, when I was a householder, maintaining the bliss of kingship, I had guards posted within and without the royal apartments, within and without the city, within and without the countryside. But even though I was thus guarded, thus protected, I dwelled in fear — agitated, distrustful, and afraid. But now, on going alone to a forest, to the foot of a tree, or to an empty dwelling, I dwell without fear, unagitated, confident, and unafraid — unconcerned, unruffled, my wants satisfied, with my mind like a wild deer. This is the meaning I have in mind that I repeatedly exclaim, ‘What bliss! What bliss!'”