Naming

Documentary: does it really exist? The momentum of this word, laid down like a trump card over and again, forecloses any further thought. There are festivals around the world gathered underneath this word, as if for shade and shelter. There is no need to ask any longer where we are, or why, all this can be summoned in a word: documentary. For some it is a credo, a way of life. The documentary, or as MTV likes to name their excursions into the genre: the real world. The name marks a line, a frame, between the objective world and its fictional doubles. Lao Tzu, a Chinese writer born too early for the documentary (anyone raised before the advent of this practice is necessarily fictional) writes: The name of a man is a numbing blow from which he never recovers.

A proposal

Documentary. Its naming is a fiction, a consensual hallucination. But why not use it here for a little longer, step into its looking glass, and when we’re done with it we’ll step out of the mirror. Though re-entry won’t deliver us to the “real world,” only another mirror where we feel at home. Still in search not for images of reality but the reality of images.

Documentary and Fiction

Do we have to make a choice? Alright then. If he hits me and gives me a black eye it’s documentary. When I explain it later to friends it is already fiction. The memory, the second time around, the aftermath, even the black eye, all that is fiction.

Boredom

Documentary only happens when I’m bored. When I’m in the high impact moments of my life, experience attains the velocity of the movies. In that final perfect fuck, the screaming break up, the first time I saw the white light coming from Tom’s face. When I am bored (nearly always), while I am waiting for my computer to start, or the train to arrive, or the stairwell to get tired of itself and stop, these small and unremembered moments which make up most of my life, are documentary, no more, no less. From these moments I don’t expect happy endings or any kind of ending at all. They just go on and on.

Shadows

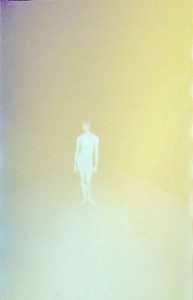

I am the shadow of my movies. It’s not what I want. What I hope for, one day, is to become the shadow of my books, but I don’t have books yet. So I’m settling in as a silhouette, a ghost, following the trail of pictures and sounds who knows where. I often get in the way, I am not yet enough of a specter, a dark double, an image, to know how to follow.

Transparency

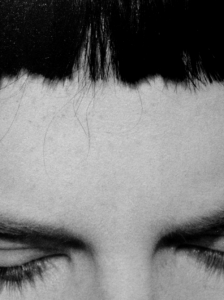

My best friend is not transparent to me. We have known each other since we secretly fell in love almost twenty years ago. It was a secret we were careful to keep from ourselves. We have survived her two marriages and how many breakups and my passing hopes and heartbreaks and the birth of her child. I never understood why people ever wanted children until she explained that the act of birth was so painful, so catastrophic, she woke up after years of being asleep. No matter what happens now, she has had her body returned to her. We talked about everything until sharing a catastrophe two New Years ago and we haven’t said a word to each other since. Not that I’ve given up hope, not at all. But my best friend isn’t transparent, the one I know the best and least, all at once. Two years now and we can’t seem to manage “Hello, how are you?” We can’t even pretend to be people any more.

Let me ask you a question. What if you wanted to make a documentary about my friend, or even about our newfound talent for not speaking? After meeting her one afternoon over coffee and maybe a drink or three you might think hey, this is a really bright, complex, funny, sad, beautiful person. And what if you decided right then, as you looked into eyes so blue they’d never show on a camera (believe me I’ve tried, they don’t make computer chips that can read that kind of blue) what if after looking into those eyes you decided that even if your movie was ten hours long you wouldn’t be able to tell her story. Not even a smidgen of the damn story. And you didn’t want to pretend either. Here, this is everything, now you know it all. That’s what every public frame (the stage, the movie screen) demands. Above all (as the saying goes, evoking a god, or at least, the omniscient viewer) be clear, deliver the speaker (in this instance my best friend) as clearly as possible, don’t leave me in the dark.

But how would you make a documentary which allows the mystery of her to remain untouched, to be able to offer a story as if it doesn’t stand in for everything left unpictured, the rest of her life for instance, or every moment of the past which didn’t make it into the frame. How to make a documentary which doesn’t need to control and contain, roping down its subject like some wild, untamed thing which requires a corral and a brand?

The temptation while making a movie is to lay all those hard won moments up into sound byte certainties, turn documentary into fiction, knowing that the audience (like me) has no patience at all. Don’t make me wait. This is what is going through my mind on the way to the theatre (I don’t like to travel, I only want to arrive). I don’t want to sit in the seat and experience the show, I want to have the experience behind me. I want to know what it is already, to have touched the thrill, to have everything in the past. I want to surrender to the darkness of the theatre but not to my own darkness, that is nothing but cruelty. You can’t expect me to pay for that, even if the show were free the cost would be too high.

Specialty Channel

After seeing that specialty channels exist entirely dedicated to golf, new horizons beckoned. If they can sell 24 hour golf, surely it would be possible to begin a channel for the kind of documentary you would make about my friend. Opaque documentaries maybe. Imagine a pal you might have had in high school who was a little unsure of themselves, retiring and unformed. Perhaps your documentary could look like this, a shy documentary which doesn’t surrender its secrets right away. Maybe never. I would like to propose a specialty channel for shy documentaries.

Nightly News

The most common experience of the documentary is the nightly newscast. The views from abroad, the successions of disaster (sometimes local, sometimes international—if it’s a bad day, it’s news). But corporate mergers have put newsrooms back into the entertainment business, so reporting in most countries is little more than an extension of ruling class mores underlining the necessities of empire. When the CIA overthrew Iraq and then Guatemala, Eisenhower lied about it. Kennedy told a press conference that he wouldn’t invade Cuba a week before going in, Johnson manufactured the Gulf of Tonkin incident to escalate the war in Vietnam, Nixon bombed Cambodia in secret. None of this is a surprise. The surprise is that government officials are still appearing on a program called the news. The surprise is that nothing has changed.

Natural Disasters

The documentary is often called upon to fill the holes left by the news. This certainly leaves it a lot of room to operate. I come from Canada, a country which imagines most of the rest of the world as a mirage, except for America of course, which is more real than the place we live. Is it possible that so little occurs in most countries (or outside of Washington) that they never appear in foreign news except during visits by first world leaders or other natural disasters?

Suffering

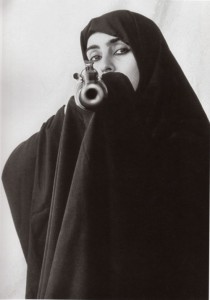

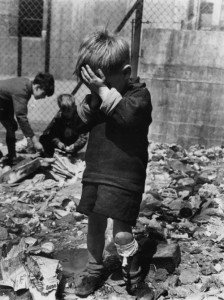

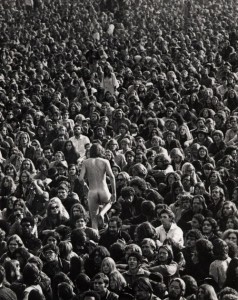

Documentaries are the one genre of the movies which have been reserved for the global underclass, rendered visible at last by the well meaning cameras of the first world, leveled at the garbage dumps of Rio, the slums of Calcutta. The voyages of discovery undertaken by Europeans in centuries past are being replayed in many of these efforts. And yet.

As someone who comes from a modernist backdrop I feel ashamed when I see these movies. They seem so necessary, so urgent in their distress. How could anyone permit this much suffering, that’s what I think, and what can I do about it? And even though I’ve just watched an excruciating seven hour recounting of a preventable genocide I have to cut my toenails and hand wash my new shirt and then I forget all about it. Though it’s not the fault of this movie that I’ve got shirts to wash, isn’t the purpose of art to deepen our empathy and compassion, to make us feel more human? This is what I tell JP Gorin at a hotel bar and he laughs and he’s not laughing with me. JP says this is classic liberal pabulum I’m serving. Don’t be fooled or fooled again he warns. Most of this work keeps the Other at a safe remove, reducing them to a pathology dished up exclusively inside the frame of their victimized state. Never mind the other tracks of their tears, the movie exists as an exclusive delivery vehicle. Oh by the way I have AIDS, it’s the only thing you need to know about me. Her parents were slaughtered in Rwanda. My son is a prostitute. This is how JP puts it, swinging the words off his gangster voice which sounds like Meyer Lansky raised on Marx. Making documentaries is a question of distance, JP insists, most films can’t find the right distance to their subject-they’re either too far away or too close (I hardly know you, why the close-up frowns?).

On the other hand these scenes of the underclass are almost entirely absent from the whimsies of what used to be called the avant-garde. Video art. Fringe movies. Call it what you will, the liberal pabulum industry remains one of the few places where the miserable may find a voice, if only for an hour, if only inside an ill considered montage and bad intentions. Even then. Even then isn’t it OK? JP says absolutely not. He feels these movies are an extension of the class war (the poor remain far away, part of someone else’s world). They are part of the perverse project that Chomsky has been outlining for a couple of decades now, the way poor people subsidize the rich.

For my part I’m still hoping that the lessons of the emulsion benders, the ones who have been busy taking apart the apparatus, might put it together again in the slums of Calcutta or the slums in their home town. As I sip my long cool Soogoo in the shade of a nasty looking after hour haunt, I hope that the long distance feeling between form and content might begin to close, even a little bit. And then it’s time for another drink. And then another. Nothing’s happening here and I wouldn’t have it any other way. I haven’t come here to forget but to put off anything new from happening. And it’s working too well.

Sammi

I meet Sammi again in Seoul at a film festival where he is immediately at home. He talks to everyone, and when they look at him in bewilderment because they don’t speak English he tries Finnish, he talks with his hands, he buys them a drink. Ten minutes after deplaning he is more at home here than people who were born and bred. In between bowing and posing for photographs with strangers who are his new best friend Sammi tells me that he’s spent the last three years working on a 40 minute film called Fokus which reworks a movie his grandmother shot in India. I guess his family used to live there. Now Sammi lives in their pictures. The images were made one afternoon in a street procession of the Maharajah, a puppet government put in place by the English rulers. The original footage is not particularly arresting, but Sammi moves his eye inside the frame and picks out details, the side of a face, a hand, and most of all the look, he lets us look at these people looking, granting us a view of the audience and of ourselves.

Editing usually occurs as a collision between two events, but Sammi’s cut decomposes these frames and re-orients them one detail at a time, drawing together moments of attention until each frame unfolds as a story of looking. Three years it takes him to arrive at this approach and to apply it. The approach, this is the important thing, though that’s not how Sammi puts it, he just shrugs and walks back into the present. The approach is the place where looking can begin. It’s not already there, it needs to be found or earned, the false suitors cast away. It can take three years or even longer. The pictures we see daily which pass for documentary, the nightly newscast for instance, don’t come from a place which requires approach, and as a result they are unable to produce pictures at all.

In the washroom I stand at the stall which has small movie posters of Burt Lancaster and John Wayne, men’s men in the men’s room, looking me right in the eye. Little wonder Sammi uses the stall instead, closing the door behind him. Over the noise of the automatic flushers he tells me, “I don’t film people.” When I ask him what he means he can only repeat, “I don’t film people. It makes me feel uncomfortable.” In other words, Sammi is busy making an approach. He hasn’t given up, he’s only thirtysomething after all, one day he will know the correct distance to take with a speaking subject, and then, and only then, will he film someone. Until that moment arrives there are movies which need to be looked at again, landscapes and buildings which require lensing. All these also require approach.

Inside the Body

Does documentary happen inside the body or only outside of it? Stan Brakhage often insisted that he was the most rigorous documentary filmmaker because he granted an image to the firings of neural explosions and cell flows which lay at the root of seeing. The out-of-focus abstractions and lattice work of scratched, baked and painted film in his oeuvre (which consumed most of his practice in the last two decades, and to which he forever resisted the label “abstract”) he felt were documentaries. The picture behind the picture, a rush of silver dust and dark corners. This is what happens inside the body, the image that emerges in response to exterior phenomena. Why is it that if I were presented with my own kidney or liver, I wouldn’t be able to recognize them as my own, pick them out of a police line up and say yes, that’s mine alright. Or even: that’s me.

My camera, myself

A picture is always centered, it appears before the eyes organized according to the hierarchical gestures of perspective. This is how the camera’s lenses are made, in order to centre the viewer. The viewer appears in the middle of each frame, SONY and JVC and PANASONIC have insisted on it. Sometimes, when I watch a documentary, this is all I am able to see, this act of centering. The director (who is increasingly the camera person), is unable to get out of the way of the movie which is trying to be seen. This is because the director is also struggling towards visibility, so the camera becomes a tool to stage his struggle (yes, it’s usually his). It’s what the manufacturers had in mind after all, the first thing the camera shows is the one who looks. The camera says: I see. Not: this is what I see. This is the most common mistake made with the video camera. People who use them imagine that the world outside appears in a flash, an instant, but what occurs to the camera first of all, all the way back in the camera factory, is the person behind the lens. The subject is born in the camera factory, that’s why these multinational concerns make the big money. Three chips and a zoom lens that takes you all the way back to childhood. Frame after frame. Field after field.

Movies without pictures

For first worlders digital video is a low cost, DIY occurrence, realizing at last the utopian dream of the 1960s, that everyone could own the means of reproduction. Instead of costly film labs; anyone can do it so anybody does. I recently watched a feature doc on the plight of a vanishing people in a remote area of Europe. It was his first film and I was surprised to learn both that it was so long and that he had decided to shoot it himself. He had never shot anything before but with all those automatic features on the camera, hey, who else can you trust? And besides there was no budget. When I finally saw the movie there was not a single picture in it, not one image that showed anything because he didn’t know how to look. This used to be a feat but no longer, and it’s a knack men have to an exponential power compared to women, the knack of producing 90 minute movies without pictures.

The problem with the DV camera is that it delivers what looks like a picture right away. Before the shooter is able to see anything the digital camera already has a picture. Or at least it delivers something which shows up in the viewfinder, which is the place a picture would be if there was one. But these are not pictures, they are pointers, they only look like an image. They are an image of an image. They outline the place an image would stand if there had been an approach, if there was time above all to look. Instead the digital camera is most often used as a substitute for looking . The camera is not raised to look, but to avoid the trial of looking. The cost of looking. The camera is pointed in order to look away . I can assure you that even as you are reading this there are people out on the street right now urging tape across the heads of their digital camcorders, avoiding the task of looking, busy day and night because they are tourists of looking, or else they have been commissioned by television which means they are professional tourists. These makers are paid to share their ability for not looking.

How many people could draw from memory a corner of their living room? Or describe how it appears differently in the morning light? In a well quoted scene from Notre Musique, a student asks Godard if small digital cameras will at last deliver on the utopian promises of a new cinema. Godard doesn’t budge in response, he never says a word. This silence is also a picture, one which is increasingly difficult to find in the data streams of the digital devolution.

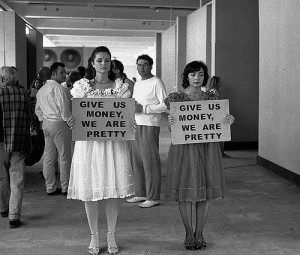

Tops and Bottoms

Fiction is for tops, documentary for bottoms. The director of fiction says put the tree here, the front door over there, the actor stands by the window. The director of fiction commands and dictates. They create a world large enough for strangers around the world to live in. But it is always their world.

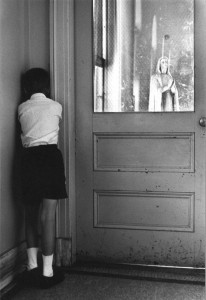

The documentary director, on the other hand, learns to accept the world as it already is. “Oh yes, of course, certainly that’s all right.” Think of the perfect guest, anything you make for dinner is fine, every conversational gambit works, this is the documentary filmmaker. She or he is a follower, a shadow, someone whose task it is to admit some part of the world as it presents itself.

The documentary maker bends over and the world enters them. Chance encounters, happenstance and surprise are their playgrounds. “Oh look,” someone says, invariably a stranger, they fill their life with strangers, and then they look. They make trips whose destination is unknown, and from which there are no return fares. When you come back, you never arrive at the same place.

This division between tops and bottoms is what makes Thailand’s Weerasethakul Apichatpong so precious. Sure he makes fiction movies, but he’s a bottom. He refuses the certainty of his own imagination, leaving it to others to decide. Not that’s he’s weak-willed or anything. But after going through the agony of raising the necessary money, he allows others to determine, to an unusual extent, what will fill the screen. This openness is, curiously enough, precisely what makes him an “auteur,” in other words he is able to get something of his singularity, some of the unspoken mystery of himself, all the way over onto emulsion and he’s able to do it not by singing me me me, but by admitting the wishes of others. It should come as little surprise that the formidable ego formations which drive most storyland enterprises produce generic, indistinguishable product. The money lenders have taught them well.

Being Dead

The practice of documentary is the most terrifying for me, because among all of cinema’s many genres it is the only one which imagines its maker does not exist. After I’m dead the world will go on just as before, and this is what it looks like: as a documentary. I may haunt one corner of it with my camera like a ghost, rattling and wheezing and trying to create as much noise as possible in order to remind those still busy falling in love and out of it that the dead are walking alongside us. This is what it means to make a documentary. Step by step. There is a world where I am already dead, every memory of me carefully expunged, the objective, non-fiction world of the documentary. Is it any wonder I long for it, dread it, embrace and recoil?

In My Room

Some people put a lot of thought into the song which will play at their funeral. For my mother it will be Leonard Cohen’s If It Be Your Will, a tune I played obsessively in my adolescence and then never again. For Richard Kerr only one tune will do, the Brian Wilson penned, Beach Boys number In My Room. Last night I was listening to the Boys’ tune thinking of Richard dying and wondering, “Is it possible to make a political film without leaving your room?” Alone, sans props or the confessions of neighbours and friends. Is it possible to make a documentary about the way someone looks out the window in the newly emptied Gaza Strip for instance, and never mention the word Jew or Palestinian, but still manage to describe the entire political landscape by looking with meticulous care and precision? I know I can’t do it, not yet, but there are other rooms closer to home which I’ve started with, trying to raise the level of attention in the light of the familiar, to find the right speed and proximity with the people around me. This is also documentary. Of course, like most people, I am always threatening to become a character familiar from the classics or prime time sitcoms. It can happen so quickly, sometimes with the turn of a phrase, like this: I love you. But it doesn’t have to go down like this. With my best friend for instance. One day we will find a way to begin again, to say the first words to one another once more. And when that day arrives I will have found what JP Gorin calls the proper and necessary distance, I will be able to make a documentary or fall in love or speak to my best friend, it’s the same thing, it’s exactly the same.

“The truth is the thing I invented so I could live.” (Krauss, The History of Love)