Satya: Not Twisting, Not Shouting

based on a talk by Katherine Miller August 16, 2016

Satya is a Sanskrit word. “Sat” means “that which is,” which we could translate as: that which has no distortion. No torque or twisting. How could we report things as they are, without adding anything extra, or withholding, or without having to provide an account of how we would like things to be (delusion)?

Twist

The idea of turning or twisting. It’s as if we meet a situation and then we turn away from it. I’m not ready to tell the whole truth yet. There is a turning away from this moment, but also a holding – something of this moment remains, as a residue, a promise even. It lingers. I’ll get back to you about that. I can’t tell you the whole truth now, I can only manage a sliver, and I’ll dish you the rest later. The moment leaves a residue, an echo, “a guilty conscience,” or just something that needs to be considered later.

Facts can be twisted, reshaped to suit one’s own purpose. Information can be falsified, stories concocted. The emphasis can be changed. One’s contribution to events could be inflated (am I the hero of all my stories?). To “beef up” a story, to make it more entertaining, to make us look more appealing, or more intelligent.

The practice of satya invites us to observe what we inject into stories. When do we pad the resume, put up a false front.

Satya – which is the practice of “that which is,” the practice of truthfulness – might have something to do with alignment. If you’re not turning or twisting away, how could you align with events, with the situation? It doesn’t mean going along to get along, but to align oneself with “that which is.” Veracity.

Stuck

Sometimes we can get stuck in our opinions. We can raise a flag of allegiance to our old views. We get locked or parked in a former definition, we come to believe our stories and can’t let them change. Can we leave our old stories behind (and along with them stale dated versions of ourselves), or at least, allow them to change as we are changing? Do we have to continue the old wars with our enemies forever?

Three Poisons

The Buddha said that we have three poisons: greed, ill will and delusion. The practice of satya is about dealing with delusion. We all have it. Delusion is one of the motors for our inner critic, the one who is forever telling us the same story about how we are not enough. This of course is a lie. Many experience the inner critic as a voice, and this harsh and punishing voice can lie at the root of our experience of language. These roots are filled with lies and delusions. We are not the terrible, weak, stupid, ugly, incapable person that our inner critic insists we are. And yet so many of us believe these lies, we treat them as if they are the most real part of the world, the final word, the truth at last. How can we live an honest life, how can we practice the yama (restraint) of satya (honesty), if our fundamental relation to language is lying?

Not-Knowing

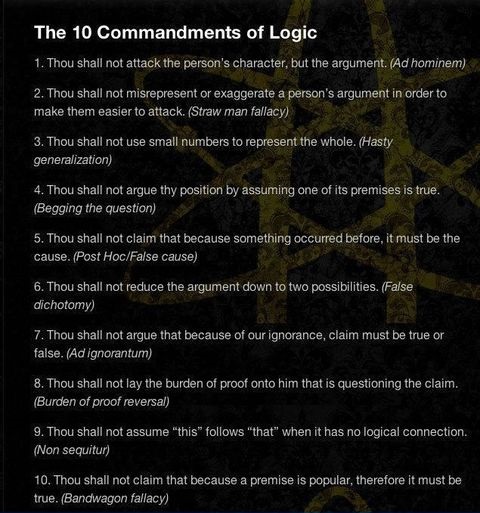

In Christian theology honesty becomes part of a moral code: thou shalt not lie. There is a line between what is good and what is bad, and an assumption that the line is clear, that one always knows. Buddhists embrace a situational ethics. The practice of satya is also the practice of not-knowing. What if there is no line? What if it isn’t clear what is a lie and what is the truth – what if you didn’t already know what to say, or what was good and bad? Sitting in this place of not-knowing is also the practice of satya.

“The Four Noble Truths are not meant to be truths in the sense of a creed that a Buddhist must believe. They are pragmatic truths, much like how it is true that if you cut yourself deeply with a knife, you will hurt and if you keep the wound clean, you promote its healing. The Four Noble Truths is the Buddha’s way of saying that, if you cling or grasp to anything, you will suffer; if you let go of that clinging, that suffering will end. The Four Noble Truths have no value in the abstract. They are verified through direct experience, by discovering how to be directly honest about our suffering and its causes.” The Perfection of Truth by Gil Fronsdal

Son

“A young widower, who loved his five year old son very much, was away on business when bandits came who burned down the whole village and took his son away. When the man returned, he saw the ruins and panicked. The took the burnt corpse of an infant to be his son and cried uncontrollably. He organised a cremation ceremony, collected the ashes and put them in a beautiful little bag which he always kept with him.

Soon afterwards, his real son escaped from the bandits and found his way home. He arrived at his father’s new cottage at midnight and knocked at the door. The father, still grieving asked: “Who is it?” The child answered, it is me papa, open the door!” But in his agitated state of mind, convinced his son was dead, the father thought that some young boy was making fun of him. He shouted: “Go away” and continued to cry. After some time, the child left.

Father and son never saw each other again.”

After this story, the Buddha said: “Sometime, somewhere, you take something to be the truth. If you cling to it so much, even when the truth comes in person and knocks on your door, you will not open it.”