100% of My Attention: an interview with Marcos Arriaga

Marcos: I was trained as a journalist. I attended a private university in Peru between 1980-85 at a time of social change. I was trying to figure out who I was and what I wanted to do.

My father was a pharmacist in Corongo, a shantytown, una barriada as we call it in Peru. From an early age I was aware of the misery of the people because I worked in his pharmacy, along with my brothers and sister, cleaning and checking the medicines. Many people didn’t have enough money to buy their medicines, or go to the doctor, so my father became their doctor. It gave me a critical perspective. The majority were Native, poor fishermen who worked in the area. Since an early age I knew that something was wrong.

My father didn’t have enough money to buy a place in downtown Lima, so he went to a distant area because the taxes were lower. He ran the pharmacy for thirty years. I worked there from the time I was 10 to 27, until I left for Canada. My siblings studied science, mechanics and nursing, but I wanted to study history or anthropology, I’m still fascinated by those stories. The university that I applied to didn’t offer history courses but they had journalism, “Communication Science” as they called it at that time. I didn’t fully engage in my studies until my second year, that’s when I started getting good profs who worked as journalists, and the political situation started developing.

My university was very theoretical, we had few facilities for technical matters. I was impressed by UNESCO’s MacBride Report (1980) that compared the influx of information moving between North and South. They figured out that there were half a million words per day moving north and 14 million words per day moving south. The amount of information we received in Peru about western culture was huge. We learned about cultural alienation in this way, and how first world media was designed to work on us.

In my fourth year I had to go into the field so I started working at a newspaper called El Diario de Marka. It was the first daily newspaper from the left. They told me just come tomorrow at nine o’clock and we’ll figure it out. When I arrived the following day they gave me some notes on a story and asked me to give it another angle. Later on the phone rang and they needed someone to go to a news conference about doctors. The paper was only interested in issues related to the working class and the unions. That was the appeal of the paper. It was the first paper to sell 100,000 copies on a Sunday. Lima had eight or ten papers, but most were very conservative.

It was very exciting. I was writing my stories and when I went back home to work in the pharmacy people would say, “Oh I saw you in the news.” I was the hero of the hood. I used to tell my dad: someone has to tell these stories.

During the six months I worked at El Diario de Marka I became interested in photography. To be honest, I was not a good writer. When my father went to the States to visit my brother in Colorado, I made a deal with him. I would go back and run the pharmacy with my mother, and he would find a camera for me. He bought a Pentax K1000 with a set of three lenses. The camera is a horse, it will last forever. That’s when I started my life as a photographer. I did journalistic photography related to the working class.

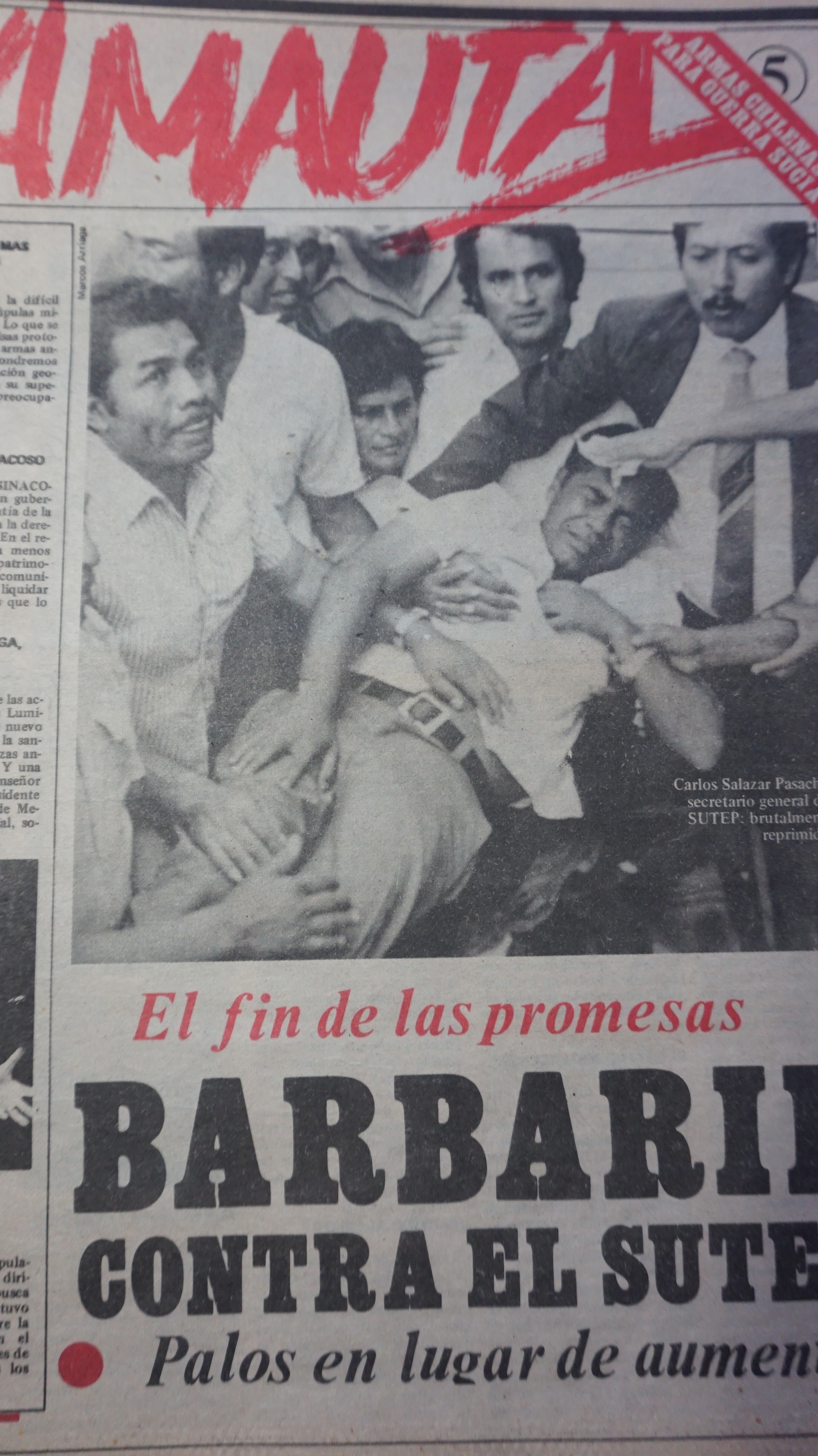

I started working again for a magazine called Amauta on issue number 4, published on May 4, 1986. The headline reads Toque que mata which means “Touch that kills you.” There was a curfew in Lima, and the army claimed that people were violating the curfew by leaving their houses, and therefore they were detained or killed. Of course these claims weren’t true. This was the beginning of the dirty war.

For issue number 5 on May 15, 1986, I made my first cover picture. We were attending a teacher’s protest with two photographers, I was the junior photographer so I was sent to support them. But when I saw all the photographers from different newspapers gathered together, I went behind the car and climbed on top of it and snapped pictures until the police came and forced me down. I realized you had to be fast, you had to be ready, you had to make your decision and move on it.

The Peruvian president was Alan Garcia, another loser. The newspaper gave me a new assignment. They didn’t want regular photos of the army, they wanted to show the new militarization of the city, how tanks and troops were occupying the neighbourhood. I went on my own.

I’m shooting a large tank and beside it I can see a soldier pointing his rifle at me. The guy motions towards me: come here. If I get into that car, I’m fucked. I stayed put, and the military came towards me. I told them I was from the press. I was wearing a press card, but they ripped it off me and threw it away. Out of the corner of my eye I saw a number of journalists with cameras, so I started to raise my voice to attract their attention. That saved me. The officer saw the cameras coming and walked away. That was very close. If I had jumped into that car I knew I would have been taken to a military base. Attacks were being made against the army, and the army was fed up, on top of that I was working for a left wing paper.

Another time, there was a big naval officer named Geronimo Cafferatta, who was assassinated by Sendero Luminoso . Geronimo was interred in a private cemetery and the marines didn’t want to let the press in. They were pissed because he was shot, and in awful way. We were trying to get in to make a picture when an officer drew a pistol, pointed it at us and said: go ahead, cross the line. Bad things were happening.

Amauta was a weekly left magazine, as you can see there is no adverting, no Coca Cola here. Eventually we couldn’t fund it anymore, we did as much as we could, and then we stopped.

At that time my sister was living here in Toronto. She had married a merchant marine pilot who was offered a job on huge boats in the Great Lakes, so she moved here in 1984. During that time my dad saw what was happening to me. It was the beginning of The Shining Path and the army’s radicalization. Even if we were not sympathizing with The Shining Path their supporters were embedded in the unions, and the ones who opposed them would be shot.

That’s when I made a decision to leave the country. It was dangerous, the newspaper had closed, and the magazine had ended. I left December 4, just before the government switched the currency on December 18 because of runaway inflation. I was blessed up to a point. I wanted to study more, to give myself a better education. It was between the United States or Canada, but the Canadians answered first. I arrived on December 5, 1987, and started working the next month in a factory where I stayed for four years.

When I moved here I worked for a few magazines, writing articles in Spanish. It was interesting to come to a country where people have a totally different view about Latin America, they were very fixated on El Salvador and Chile. I had funny political conversations on Bloor Street, where I met a lot of people. I met a guy from Brazil who was going to Sheridan College and he told me about his experiences. I had lost my factory job after four years and was looking for another and someone said: “You can collect unemployment insurance.” What is that? They pay you? Then they told me: if you go to college the government will give you money. Really?

I went to Sheridan College in 1992, my interviewing group included Irene Holdham and Jeffrey Paull. I showed them my pictures but confessed I still had problems with English. They told me: don’t worry about it, please come. I was thirty-two years old and went for three years. That changed me. I started making cinema here in Canada, in Peru I could only do photography. The first year was filled with a lot of assignments. I was very diligent and had to master the technical aspects. In the second year they choose 15 people who get to make 16mm films. Of course everyone wanted to go into this course that was being taught by Phil Hoffman. He told me: don’t worry about it, you’re on the list.

When I started with Phil I realized that I needed material, I had only still photographs. I had become a Canadian Citizen which meant I could finally leave the country. So I went to Peru with a super 8 camera and five rolls of film. When I came back I learned the famous optical printer (a device used to rephotograph film). My first film Watching (8 minutes, 1994) is telling you: watch. I want you to see this. Sometimes we see without seeing. I started slowing some actions, that’s what I like about the optical printer, when I arrive at the image I need I can add more frames, I can slow down an action, so the audience can become aware of this moment.

I embraced 16mm right away, a lot of it was familiar because of my photography background: aspect ratio, f stop, shutter speed. Photography is about framing, and framing as a photojournalist has to be quick because there’s no time or money. All of that worked for me.

Jeffrey Paull was my first professor, we fought for him to teach the Frame by Frame course (a mix of animation history and optical printer assignments) even though we had only five students in the class. We were into avant-garde cinema. Jeffrey was a very practical man. His first assignment had a long list of prohibitions, there were so many things we weren’t allowed to do, and then at the end he said: be creative! Jeffrey was always pushing you to see how much you were going to follow the rules and how creative you were going to be.

Jeffrey and I watched the five rolls I shot in Peru and he said, “You could save 1/3 of that and the rest you can throw in Lake Ontario.” Years later I asked him, do you remember telling me I should throw away all that film? He asked, “Did you do it?” I said I didn’t. “Good, good.” I always enjoyed Jeffrey.

I was working in a restaurant in Toronto and commuting to the college in Oakville. Jeffrey used to come by and pick me up and drive into the college. I used to buy packs of ten tickets for the GO train, and had to extend them as much as possible. Phil Hoffman used to have a little studio around this area, he would also give me rides.

Mike: Sheridan embraced a mix of personal and documentary cinema.

Marcos: I remember seeing Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929), wow. That was done in the 20s? Phil showed us La Jettée (1962) by Chris Marker. I remember you came to the class and talked to us, you showed us a film called Shiteater (1994). I was totally taken by the high contrast black and white.

After college I joined LIFT (Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto) in 1995. They allowed me to get equipment, and to start shooting for others.

Mike: Did you feel you were joining a community?

Marcos: Totally. Many are still good friends, and we were very open with each other. I got to know Roberto Ariganello at that time, he had just joined LIFT and would later become its director. We were making personal movies in a very supportive environment. I never felt that certain kinds of movies were more important than others. The equipment went out equally to everyone. Sometimes immigrants wonder if we’ll be accepted or not. But I remember Lisa Hayes (who worked at LIFT) asking me: what’s your name? Do you have a film? Do you want to show it? Would you like to do volunteer work here?

Deborah McInnis was the director, and one day she asked me if I knew where the bank was. I said sure. She handed me a bag and said please take all this money and deposit it in the bank. All these messages were being thrown at you from the co-op. I started working with Deanna Bowen who was in charge of events, and I became the official projectionist. We held monthly screenings that mixed drama, experimental, documentary and animation, the boundaries were fluid. After that came 3 Minute Rock Star (programmed by Jane Farrow and Allyson Mitchell on March 30, 1997) a festival of super 8 films. I did the projection for the festival with my good friend Jeff Sterne. Lisa did the sound. The most popular LIFT event was an annual screening on Ward’s Island, with a picnic and a soccer game.

I was excited to work on El Barrio (The Neighbourhood) (10 minutes 1998), which dealt with how I perceived Toronto, especially the downtown core, the colours, dancing and movements of multiculturalism. I filmed in Chinatown, Little Italy, and Christie Pits that used to host a Latino festival. It was my way to embrace and create an homage to multiculturalism. I used what my friends called crazy camera, camera loca, shooting frame by frame as I moved through events.

I was also working on a film with Jeff Sterne called The Harris Project (15 minutes 1998), named after the Ontario premier Mike Harris. After the NDP government of Bob Rae, there was a move to the right. Jeff, Jorge Manzano and I met in a restaurant where I said we’re not documenting anything, we should figure out what is happening. There were a lot of protests against Harris’ austerity budgets. Of course I was very excited because I thought it was going to be like Latin America. Police, bombs, marching! I remember telling Jeff that I didn’t know if they were going to expel me because of my political beliefs and he assured me that doesn’t happen here. We could go to the protest marches and film and it would be fine.

We shot four or five marches, then realized that all the marches were the same and we didn’t need more. We shot on film, for me it was always about film. I always have film in my refrigerator. One of the movies I made at Sheridan College was called Watching, and it was screened at Pleasure Dome, and after that it was sent it to a student film fest where it won the best cinematography award so they sent me 2000 feet of film. (laughs) I told Jeff we have film, let’s go shoot. Jeff had a car, Jorge Manzano offered to rent a Bolex camera for ten dollars a day. Then we started collecting images.

Mike: The movie relentlessly interrogates the conditions of its own making.

Marcos: The structure is interesting. We announce that there are four filmmakers who are trying to do something for the good of society, but at the same time these intentions are twisted. I was in charge of the images, including principal photography, the optical printer and the editing. Jeff was in charge of the sound, to create a dialogue, and to help me put it altogether. In the process of making the film, Real Brown announced there were too many boys at the table and dropped out. Six months later Jorge said this is too slow so he left. Jeff suggested that this was another aspect of making the film, like too many people today, we don’t have money, let’s document how a movie is made under these conditions. Now we see neoliberal governments in power, but Harris was the first instance of neoliberalism here in Ontario. We saw how they attacked the unions, the teachers and schools. Now we know. But at that time nobody knew.

At the time I was getting to know other filmmakers like (the late) Cara Morton who was working on Across (3 minutes 1997), which she shot at Phil Hoffman’s Film Farm, a very beautiful film. Elida Schogt was working on her film trilogy. It was an interesting time, we were producing a lot of material.

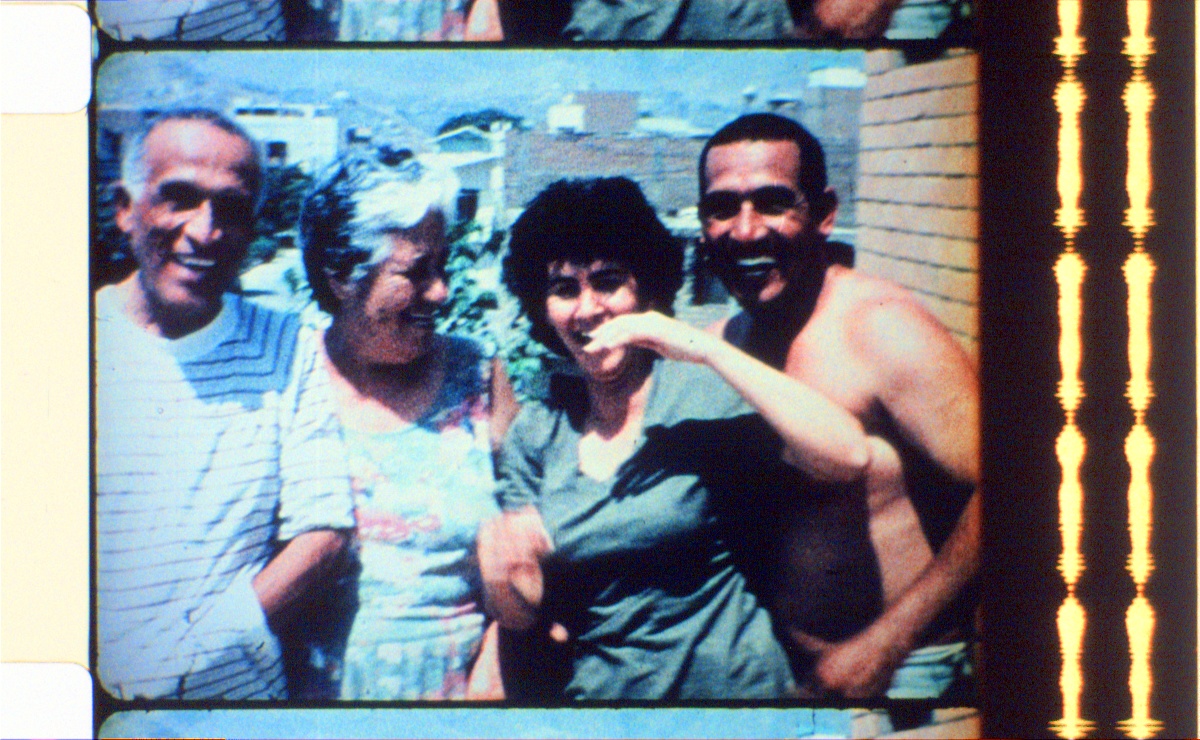

After that I decided to go to York University. Cara assured me that York was good for her. I began my MFA in 2000 after talking to Phil Hoffman who was teaching there. At the same time I decided to make a film about my family called Promised Land (21 minutes 2002). It had been a long time since I saw my entire family together, my older brother left for the United States when I was ten, my brother Carlos left a few years later, and then my sister Maria moved to Toronto. The last time I had seen my siblings together was when I was ten years old. This was the result of bad governments. People forced to leave the country became a motif that could blend the historical and personal. In voice-over I talk about my mother and father, and explain how they left their cities. They were part of a wave of industrialization that occurred across Latin America in the early part of the twentieth century, but development was uneven, money and power and industry were centralized.

Promised Land was released, and I was lucky enough to get into the Hot Docs festival (2002). People believed in it. I remember showing it to Deirdre Logue, who was the director of CFMDC (Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre). “Please could you do me a favour and look at it, I’m still having my doubts.” Later she said “I’m Irish and I can relate to this, I know exactly what you’re talking about.” That was reassuring.

I didn’t mention anything to York about this piece, instead I proposed another movie called Maricones (Faggots) (52 minutes 2005). By the 90s the gay movement in Toronto was very strong. When I worked in Peru I saw the first pamphlet from a gay group promoting a march in Peru. They used the expression conducta inapropiada – “improper conduct” – and insisted that whatever is inappropriate for you, is appropriate for me. I was completely taken by their language, it was clever and strong. Eventually I got to know people in the gay movement.

When I applied to York I had to make a proposal, so I offered to make an exploration of the gay movement in Peru from my point of view. I wanted to interview gays from my neighbourhood. The proposal was accepted and I received $5000 and quickly realized it wasn’t enough. I did whatever investigations I could from here, but switched the project into a local community garden documentary. Little Square Heaven (21 minutes, 2003) reflected the diversity of many different kinds of plants and fruits, and that reflected the gathering of a community.

When I left York I applied to the Canada Council to research Maricones and boom they sent me the money. Usually when I do my documentaries I take my time, I like to travel and gather information first without shooting. I like to talk to people, visit locations, buy as many books as possible. When I was clear about how to proceed, I wrote up a proposal, submitted it to the Canada Council and they gave me $40,000 to shoot it with Jeff.

Mike: It’s a very intimate documentary.

Marcos: Particularly because of Eusebio, who was 58 years old and living in Corongo, where I grew up. I’m a heterosexual person, I didn’t know how he was going to react to the project. How was I going to approach him?

My parents had closed their pharmacy and moved to Lima, though they never sold their property. I was with my parents on the bus, going back to the old neighbourhood, and as soon as we got out, who was walking there right beside my parents? It was Eusebio! I thought God had sent him to me, it was meant to be. Eusebio and my father embraced each other. My father had been a doctor for people in the neighbourhood for nearly thirty years so everyone knew him. He introduced us. “Do you remember Marcos? He wants to make a film, why don’t you talk to him?” I believe in signs, you don’t expect them but they just show up. I eventually shot many people, but when I brought it to my editor (Alexis Hurtado) he told me: these two guys tell the whole story, cut the rest.

I tried to focus on the human part of the characters. I also interviewed trans folks and women but eventually I found that I was lacking the knowledge I needed to talk with them. I thought of making a sequel because I kept hearing their stories, and some were really sad. Some inject oil in order to create breasts, or go to non-professional doctors. There were awful cases, but it was too big an issue.

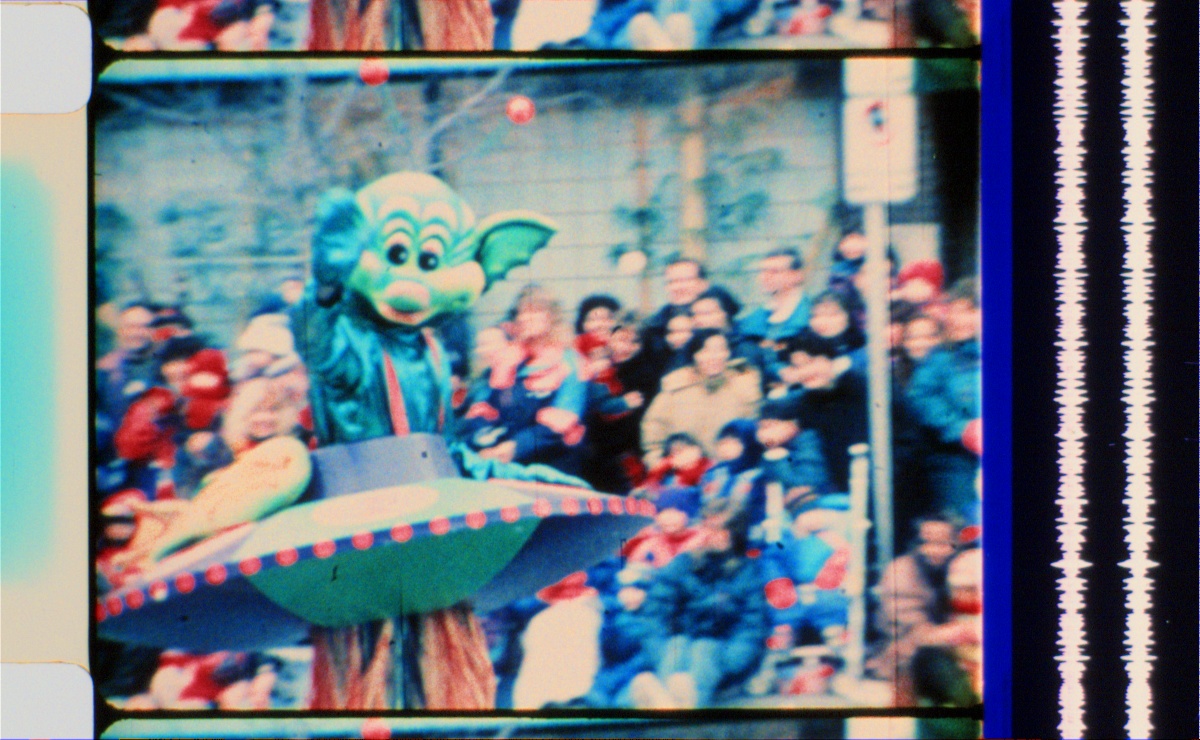

On my first trip I found my main character Eusebio, and met with some of the leaders of MHOL, the homosexual movement of Lima. On the second trip I found the second main protagonist Juan Carlos Ferrando, the son of one of Peru’s most famous television personalities. He studied film and television in Europe and at the BBC in London where he first discovered that it was OK to be gay. Currently a drag comic performer, he owns a successful theatre and is one of the organizers of Lima’s fledgling annual Pride Parade which I shot in June.

At that time I started using 16mm film for B roll footage, and used a Sony PD150 (video recorder) for interviews. That worked very nicely.

When it was finished I called Frameline – the international lesbian and gay festival in San Francisco. The submission deadline had passed but they said ok send it, and a week later they called and told me it’s in. There were three or four festival invites from that screening, the film seemed to move itself, eventually it was invited to more than twenty festivals.

I used Peruvian music but didn’t secure the rights, so it couldn’t be sold to TV. I never tracked down the rights, I was too tired. I had already produced, directed and shot. I usually don’t edit my films, but I’m very clear and diligent about my images, I shoot with a lot of variety, I like to help my editor. I do edit my shorts, I enjoy making something with a four-to-one shooting ratio. But if I have forty hours of material then I’d rather have an editor. I tell them my ideas, send the footage, let them make a first pass, then I jump in and tell them what I think.

I came up with an idea to make three movies: the first would contain three scenes in super 8, the second three scenes in 16mm, the third three scenes in 35mm. These are the three formats I use in film. 35mm is more dramatic, you have acting, it’s the Hollywood standard. 16mm is more experimental, more documentary, more moving camera. Super 8 was freer, more like home movies.

3x 16 (9 minutes 2007) was unplanned. I shot it first, and then the ideas came. The first scene shows a young boy playing with a soccer ball in Lima’s Plaza Manco Capac. A statue dominates the square showing Manco Capac, the first ruler of the Kingdom of Cuzco, and later the Inca Empire. I remember telling Jeff Sterne, okay, let me bring you to this plaza, because I always complain that in Toronto we don’t have a plaza or a memorial statue to embrace the Indigenous origins of this city. Jeff and I started shooting the statue when this kid showed up and started making all these little gestures with his ball, and I thought: let’s shoot it. After it came back from the lab I knew I didn’t have to touch a frame, it was done. There was a brief moment of shoeshine boys that were out of focus but I thought no, just leave it, don’t try to make it perfect, even the imperfection will add beauty to the film.

The second section shows my mother. We live in the north of Lima close to the mountains, not in the fancy part close to the ocean that some like to compare to Miami (but why not San Francisco, New York, Boston?). A lot of Native people live here, and my mother is kind of Native. I woke early that morning and saw the mountains were clear. Wow, better get the Bolex and start shooting. My mother told me she would put her clothes up on the line so I began shooting, waiting for my mother to come. I had my 10mm lens, the 25mm lens, and 75mm. It was sunny so everything was in focus, at f8, what else would you expect? My mother comes and hangs clothes out on the line. Again, when I saw the footage it was perfect, nothing had to be changed. The challenge was not to edit the piece.

The third movement was shot back in Toronto where I had started working for the Toronto International Film Festival. I decided to do some timelapse, shooting a roll of black and white film in the revising room of the festival. Martin Heath was in charge, I remember him saying, “I want filmmakers who work with their hands!” He has so much knowledge. For ten years I revised small 35mm films and features. They used to call us in August, and we worked in the Manulife Centre, or in a bar on Carlton Street, or in the OPP building. We would set up our tables and receive all the films. We spliced together all the different reels of the film, inspecting them for sprocket damage. At the head of the reels we had to splice in the trailers for the different programs – Perspective Canada, Planet Africa and so on. You had to be very careful that it was the correct trailer with the correct aspect ratio. There was Martin Heath, Kate MacKay, Sebastjan Henrickson, Alexis Manis, Petra Chevrier, and others, a very interesting crowd of people. I did that for ten years until I got my job at York University.

Mike: These three different scenes come together to make a single movie.

Marcos: It was easy to put together because there was no editing, I just had to add a title. I presented it the way it was shot, all decisions were made in-camera. I thought I could do the same in 35mm, using three characters. I applied for money, and even though I didn’t expect it, they sent it to me. It was the first time I worked with actors. I wanted to work with real homeless people, but I was concerned about stereotypes, and thought it would be difficult to control. I brought the camera low to the ground, the people who don’t have anything live in the lowest areas of society, so I chopped off the heads of anyone who had more means. Tale of Winter (6 minutes, 2008) is about three homeless people. It was intended to be a criticism of society but I was given a lot of money and shot it in 35mm. I should have given most of the grant to the homeless and shot it on digital. That was brutal, it defeated my entire story.

Mike: Your longest movie to date is a nearly feature length documentary shot in the mountains of Peru called Looking for Carmen (68 minutes 2012).

Marcos: Carmen used to work with me at the newspaper, and more than that, she was caught by the police, and her arrest was presented on TV two weeks before I left for Canada. A cell from the Shining Path had been caught. I kind of knew that she was part of the SP, we had arguments when we worked at the paper. She was a hard core militant. We were both in our early twenties, and we used to go out together for lunch. She was a secretary. I remember one day we had an awful argument because I was very critical of the SP, I said you don’t have to start killing people just because they don’t agree with you. She told me that when the SP took control we’re not going to kill you, we’re going to re-educate you. Oh really? I felt their analysis of historical structures in Peru was incorrect, they were giving the army reasons to come down hard on all the left-wing groups.

I’ve started investigating militarism in Latin America. It started in Brazil in the 60s then moved on to Chile and Argentina. It was motivated by the United States in order to suppress left-wing movements. The case of Peru was quite different, there was a coup d’etat in 1968 led by a military that was quite progressive. They began agrarian reform, educational reform, and nationalized the oil industry. I remember reading an interview with a top military man who claimed that their reforms cut the hands of all the left groups, it was more effective than fighting against them. Of course they did everything half way. They gave land to the Natives, but they didn’t give them the resources to work the land, because they didn’t want them to control the resources and prosper.

During the 1970s there were extreme fascist governments throughout Latin America but not in Peru. My father, for instance, looked to China for his political attitudes, and he had no problems. You could go to downtown Lima and buy Mao’s Little Red Book. This wouldn’t be allowed anywhere else in Latin America. The government was more tolerant, though they were also busy infiltrating groups, and cutting every attempt to create guerilla movements. The Shining Path changed that. They were around in the 1970s based in Ayacucho, a city in the middle of the Andes where they didn’t do actions. Instead, they worked slowly and steadily, creating small groups. Their actions began after the military left the government and democratic elections were called in 1980. The first action was to boycott and burn the electoral material in the small town of Chuschi in the Andes. Their stance was: we don’t want to support any bourgeois democratic process, we are the new democracy. They started becoming news in 1981-82, while I was studying journalism. I studied with a guy whose father was one of the Martyrs of Uchuraccay. Eight journalists were attacked and murdered by peasants, but some critics believe that was done by military troops dressed as peasants. That was the environment I was in when I lived in Peru.

Mike: Looking for Carmen is a great act of grieving. You enter villages that have been devastated sometimes by government troops, sometimes by paramilitary groups. The violence feels indiscriminate, but at the same time widespread and systematic.

Marcos: There were three visits to Peru to make this film. At first I was looking for a way into this story of searching, disappearance and loss. I was planning to do a documentary that I would be part of, and that would reveal what has happened in Peru. But as soon as I heard the stories that people had to tell about their loved ones dying, I made a conscious decision to remove myself from the film. Nothing I could say could compare to the loss and pain of these witnesses. My personal stories were nothing compared to theirs. I have it easy.

When I made my first inquiries about Carmen I was told that she had been murdered, her body hadn’t been found, but she had been disappeared. I tried to look for people who were with me in the newspaper, people who could help me trace her. The first person I met was Jose Luis who worked with me at the paper, and then went on to become the press assistant of the president of Peru in 2001, so he was not going to talk about it. That was one of the first things that I learned. People who had been involved with progressive ideas were now, after fifteen years, in a different situation, so they forgot about their past, they didn’t want to talk about it. I invited him to a really nice bar. I started with “Do you remember this? Do you remember that?” and then after half an hour I started asking about Carmen. The answers became shorter and shorter. He didn’t want to get dirty.

I searched hard for Ernesto, he was my supervisor at the paper, a really nice man. He’s the one who talks at the end about photography. He’s an old leftist militant, still a believer, but it was hard to find him. I asked him to tell me about Carmen. He told me: “As far as I know, she’s been killed, but let me figure it out, leave it to me.” I came back to Canada, taking all the material I had gathered and started rethinking the project. Ernesto sent me an email months later: Carmen is alive.

After the first time they caught her, Carmen was released after a few months because they couldn’t prove anything. Years later she was caught with a lot of Shining Path material, so she went to jail. There was a revolt inside the jail, and that became the motive for the army to enter the jail and take it back. There were 300 or 400 Shining Path members there, they began by killing more than a dozen men, then made everyone lie on the floor and picked out SP leaders and assassinated them. When the bodies were checked later all of them had a single shot in the head, so it was obvious what had happened. The resulting scandal was huge. President Alberto Fujimori granted amnesty to the surviving SP prisoners so long as they could find a country that would receive them. Carmen was one of the survivors. Ernesto gave me all that information.

I managed to get court transcripts of her trials. I needed to know what I was getting into. The last thing I found was the email address of an organization that she was appealing to for her brother. Her brother was a leader in the Shining Path, and her sister and brother-in-law were also involved. The main leader in the SP was Abimael Guzmán, the second in command was his wife Augusta La Torre, the third in command was his lover. It’s a tradition in Native culture, in cultura nativa, you surround yourself with family. It’s still prevalent today in business and politics.

I sent an email and after two weeks she reacted. Oh, she wrote, you were that little, dark-skinned negro, the blue-eyed black with the big smile. We began a conversation. She left Peru but I can’t tell you where she is, that’s part of the deal we made. She told me listen, more than twenty years have past, I have two kids, teenagers. For me to go back and remember is painful, I lost not only close friends but family. I saw people being killed when I was in jail. I like you a lot, but… It was a very heated conversation, but in the end I had to respect her decision. By that point I knew about other cases that I had to follow up on.

I went back to visit for a second time. The first two visits were paid by a $15,000 research/creation grant from the Canada Council. In those two years I travelled to Ayacucho, got to know my people, but I didn’t shoot anything. I showed them Maricones and told them I would come back after asking for money to shoot.

As I wrote my proposal I began to reconsider my initial ideas, if Carmen wasn’t going to be directly involved, how could I tell this story? The Shining Path was alive in the 80s but hardcore actions started in 1982, when they bombed electrical grids and darkened entire cities. They used terror to make people afraid. It was not a typical guerilla group with an active front. The Shining Path was very organized, they would dynamite the power stations, arrive in darkness, burn down three or four factories and police stations and leave. The army didn’t understand how to deal with them. They rounded up everyone on the street and tortured them, usually arresting or shooting passersby and civilians. Journalists would ask people: tell me your name. They would write names down, and the following day a notice in the paper would read: we know that these people were in the square, their names are… and they were taken alive. Why have they shown up dead? The army didn’t like that.

The stories that needed to be told were happening in the Andes, that’s where the major crimes happened. I went back for a month, and travelled all around Ayacucho with Noah Bingham, my camera person. I also hired Ernesto, he knew that area, and I wanted to help him. He wound up giving me all his photos. He was a great photographer and was getting peanuts. It’s awful what happens to artists, nobody cares about what they make. How can you know the history of your country, the history of your people?

As soon as I started hearing their stories I told the cinematographer: put the camera there, frame it, and let it run. Usually I like to do cinematography, but on this film I did only B roll camera on super 16mm. I wanted to listen. When I made Maricones, I did the shooting and was also the interviewer, but I lost too many details because I was worried about technical questions. Now I said: please tell me your story. You deserve respect, I need to give you 100 percent of my attention.

Mike: The people who you met didn’t hesitate to talk to you. It seems that they hadn’t been asked before, no one had come before you.

Marcos: What is fascinating about their stories is that you can feel in the way it’s delivered that it’s real. It was painful trying to cut it. People spoke about the death of their loved ones for two or three hours, and I had to cut little sections. Jorge Lozano was my editor. I needed someone who understood Spanish and who knew the political scene in Latin America, Jorge was perfect for that.

The film hasn’t been shown, nobody wanted to touch it, I don’t know why. Maybe the topic isn’t interesting anymore. The Latin American topic, the topic of Peru. Sometimes I’m fascinated by the way the western media talk about Salvador Allende. They’ve been talking about Allende for the past forty years, 10,000 people were killed in that awful coup d’etat , and it shouldn’t have happened. But 70,000 people died in Peru and people don’t talk about it here. For the western media only certain countries are in focus.

When I started working as a cinematographer I worked on a lot of Native films. The first film I shot was also Jorge Manzano’s first film. City of Dreams (28 minutes 1995) was about Marcel “Bambi” Commanda, an Ojibway man from Rama First Nation. I knew Marcel as an artist and an alcoholic, he used to hang around Future Bakery with a bunch of us. I remember Jorge telling me that Marcel was going to come. We only had two or three shots left to do with the heavy Arriflex BL camera, it was noisy and we were going to shoot in a basement. We created a little jail. After that Marcel was taken to a hospital and three days later he passed away because he was so damaged by alcohol.

After that Jorge Manzano made Johnny Greyeyes (78 minutes 2000), about native women in prison. Then I worked as cinematographer for Shelley Nero’s film Honey Moccasin (49 minutes 1998). A short time later, I met another guy from Alberta, Clint Tourengu (aka Clint Alberta). He went to LIFT and met Roberto and said that he had $8000 and needed someone to shoot his film and help him direct. Marcos can you help him? I shot that film, and later this kid got so excited he came back to me and said, “Listen, I have $150,000 from the NFB to make a film!” Deep Inside Clint Star (88 minutes 1999) was about Native sexuality, and we travelled through Alberta. That film eventually went to Sundance and won a Gemini award here for the NFB. That was my first contact with heavy Native culture. Jorge Manzano’s film also went to Sundance that year, though of course nobody cared about the cinematographer. Then I got another job, with a group called Seven Generations who had a gig with APTN (Aboriginal People’s Television Network). I shot nearly the entire first season. We travelled all over Canada to bear witness to the reality of Native people. I was haunted by a single question: why?

I’m a mixed race person. I have thirty percent black, thirty percent Native (Inca), some Spanish. I remember a moment at Sheridan College when we were going around the table and someone said “I’m Irish,” “I’m…” and when it came to me I said, “I don’t know really, I’m a mix, I have a little of this and a little of that. I’m Peruvian I suppose.” When I was in Peru you had to learn the names of the fourteen Incas, it’s embedded in our national history. But here in Canada I don’t see Native history. I still don’t see it. The integration of Native culture — to embrace their heroes and food — that’s what creates a nation. Travelling all over the reservations, I could see how segmented and secluded they were. I thought whoa, what’s going on here? That’s what I don’t see in the arts here. Oh look: another picture of Marilyn Monroe. How many Marilyn Monroe do we need to see? Why don’t you put up a picture of Tecumseh?