Collaborating on a Mystery: an interview with Stephen Broomer (2016)

Mike: I wonder if you could spare a few words about the evolution of the media arts community here in Toronto. You’ve done some deep digging into the roots, how do you feel it’s evolved, what have we become?

Stephen: I see our community as being in the thick of an ongoing crisis of historical awareness. My work on the community’s past is largely anchored in the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s, and runs the gamut from the most fragile works of the underground to the most acclaimed. But even in underground filmmaking, the most acclaimed works are vulnerable. The facts of that history, its makers and works, have become arcane.

Canadian filmmaking, much of which was anchored in and around Toronto, had persistent themes that emerged out of some northerly collective unconscious. Jonas Mekas said it had an especially fine density, speaking of it in the ‘60s at the cusp of structuralism, and later we have these arguments over the role of text, material self-consciousness, landscape and isolation, autobiography, and so on, themes which hold true across many bodies of work all through Canadian modernism. I don’t believe that art extends from theme, but that it comes from a force of individual will, and I’m more interested in freely improvising than in synthesizing a mode, but that isn’t to deny the presence of those themes in my own work.

I suspect that any attempt to locate themes in Toronto’s contemporary media art community would meet with argument and contradiction, and I wonder if that’s because we have less and less of a sense of place here. Perhaps many filmmakers, and for that matter, curators, see no distinct culture here and figure it only as a blank slate. Those Toronto filmmakers of my generation with whom I identify most have a strong sense of what came before us, such as Eva Kolcze, Clint Enns, Daniel McIntyre, Christine Lucy Latimer, and Dan Browne.

Mike: Toronto is firmly in the grip of a neo-liberal transformation, bigger is always better, the real estate prices are soaring, downtown is being priced out of reach of the young. When you speak of work coming “from a force of individual will,” how is that different from the everyone-for-themselves ethos of hyper-capitalism? What place does fringe movies have to play in this neo-liberal project, is it marching in step, or can it still be imagined as a place of resistance?

Stephen: I don’t see any correlation between what I’m calling the force of individual will and the selfishness of late capitalism, because what I want to see flourish is an art of sincerity and integrity, born of personal commitment, to foster the intellectual and emotional freedoms that society is increasingly steeled against. Many of us may be set to recoil at the sound of “individualism,” but I believe that artistic communities are at their richest when their step is set between individuation and collective support. The more personal a work is, the more universal its impact. The problem arises when art only serves the ends of coddling an ego.

The films I make that deal with Toronto are not about Toronto the Good, nor Toronto the prosperous, nor any other myth of the city; they’re Toronto rescriptus, Toronto in reply, the dream-life of a city, sure, but nowhere near an ideal. And with our films, we can make its high-rises transparent. We can change their colours and make them porous, to give them textures of the heavens or set them reeling into inferno. If politicians and developers transform my city, I will transform it in turn.

Those values cannot be reconciled with the neo-liberal transformations of which we speak. I do believe that underground films must remain defiantly underground, or at the fringes, as you’d have it. In the context of Toronto, I believe there has been a great divide between what local artists want and need, and what exhibitors are willing to support. This is an art of outsiders. We have nothing to sell. We’re lucky enough, sometimes, to have sites of freedom where we can share our work.

Mike: At last year’s Zoë Heyn-Jones show, which you programmed, I really appreciated your thoughtful introduction, and that you came prepared to have a real discussion. I wanted to ask you a question about critique. I understand that production and exhibition are necessarily related, how can artists’ work get better if we can’t share our yields? You provided a very caring and supportive environment. Would it be ok to offer critical comments, the kind that usually pass in private amongst media makers after the show, quietly, in the dark? Is it possible to create a space where it would be alright to voice concerns or observations that aren’t only boosterism, or would that only shatter confidences that are already too low?

Stephen: I’m grateful that you felt that I had honoured the work. Here’s a question I’ve struggled with — on critique — I’m torn, of course, but my sense is that we have to speak from the hip, and to the work most likely to move us, work that is worth investing our response in, as I believe Zoë’s is. You use the word boosterism — this is something I feel we ought to be mindful of, to temper, at least as a kind of all-consuming position; I imagine sheer boosterism as a habit that soothes our doubts too quickly. One of the things I admire about Clint Enns is his wide-ranging sense of support for artists of all stripes, creating opportunities for a massive volume of new work. I’m a bit more narrow — my sense is that I can only devote myself fully to work that moves me deeply, and there, of course, I’m eager to invest my honest concerns. What kind of space do we create for such feedback? The kinds of critiques that you describe strike me as being largely absent from our community not because of the existing spaces but because of the utter lack of critical thinking and writing. If nobody writes, and nobody reads, that quietly muttered critique, whispered in the dark, becomes less and less informed. I’ve been trying to do my part with writing on my peers, but I think the disconnection between the worlds of poetry and film has just further decimated the ability of artists to write on their own work and on each other’s work. In 1966, John Hofsess wrote a series of articles for the Varsity (University of Toronto newspaper) that took on this question of how a filmmaker grows — stating that they needed, among other things, screens to show on and spoken and written feedback, from audiences and critics. In my view we have neither in Toronto. You ask if the confidence is too low. Well, if we’re too naked up there when we’re thrown onto these screens, maybe we have to grow a thick skin. There’s a lot of heartache and competition and a lack of brotherhood waiting in the experimental film world, as with everything else, angles and the ulterior motives. It can be a misery that’s only made worse if you have no opportunities to trade visions.

Mike: How do you account for the present divide between artists and programmers in the city? How have historical trends/forces in the city moved us to where we are?

Stephen: In the ‘60s we had for-profit ventures like Cinecity, which were sustained by the large audiences that underground film attracted. The programming there was fairly flexible and accommodated a lot of arthouse narratives and documentaries, but they were running underground screenings pretty much seven days a week, and they would show movies like Stan Brakhage’s The Art of Vision (4 hours, 1965) and Ed Emshwiller’s Relativity (38 minutes 1966), as well as films by Toronto artists issuing from the newly formed CFMDC. Through the ‘70s and ‘80s you had artist-run organizations like the Funnel that, in a sense, filled in the gap left by the closure of Cinecity, and then you see the emergence of other groups that carried on programming underground films, like the Innis Film Society, Pleasure Dome, and later the Loop Collective and Early Monthly Segments. In every case, whether we’re talking about artists or non-artists organizing these screenings, we’re always talking about people who loved films and filmmaking, and who wanted to exhibit and consume as much as they possibly could, and to support artists and give them platforms.

The first underground film programmers in this city to do anything truly significant were Lorne Michaels and Rob Fothergill, who programmed the 1967 Cinecity Cinethon together. They were budding filmmakers, sure, but, more importantly, they were young people immersed in the culture of the underground. They weren’t afraid to show dangerous work. They didn’t flinch showing Warhol’s Vinyl (70 minutes 1965). They also didn’t make claims to intellectual superiority via their arrangement of films in programs. One played after another. Every few minutes you’d see something different. They didn’t program with claims that they had divined meaning from our out-of-focus, overexposed, and occasionally upside-down movies. They programmed from a position of passionate support. I’m no utopian, but as an artist, that to me is the ideal.

We’ve fallen far from that passionate intensity. I suspect that other local artists feel as I do that many among our city’s media art programmers contribute and risk very little, usually with a safety net of arts council funding, a benefit that many of us have been repeatedly denied. Meanwhile, some of us are desperately trying to make films with virtually no support, and with limited means to build a local support network because we can’t get our films shown locally. I would like to be able to defend a programmer’s discretion, I don’t think any of us relish the idea of forcing people to show our work. But I have never heard a compelling explanation for why so many Toronto artists of my generation have been denied local platforms.

My ideal programmers are those who are interested in building opportunities, in opening doors. I say, let everything be seen, give everything a space, and if one believes as I do that time often discriminates on its own, and that the strongest work endures, then the only things that matter are our wits, our sincerities, the individuality of our visions and the fellowship that comes out of that. I believe that personal cinema is founded on love, on inclusivity of form, on individual expressions made by a cast of outsiders somehow protected by their own hubris from premature burial, even against all the selfishness and willful hurt we cause each other, through successive generations, ideological and personal differences, juvenility, exclusions, jealousies. Community problems have never changed my work, they’ve only distracted me from it. We have a lot of things to be glad for in this city, in terms of having a rich and diverse film culture, but where it concerns those now neglected, we have to do better.

Mike: Some artists speak of a turning point, a calling even, that led them into practice. Was there a moment that started your media making?

Stephen: I wish I had a definite turning point, but the path I followed was riddled with misdirection. I was interested in improvised music, when I was a teenager my interest was divided between film and music. By age 17, I was a bit more determined toward filmmaking, by way of dog-eared copies of Sheldon Renan’s An Introduction to the American Underground Film, Kevin Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By, the Eisenstein books. I was full of joy and rage and sorrow, and even then knew I’d better find some constructive way of casting that out into the world. I went to school to study film, with a strong interest in underground film, and I was distracted from my passion by the industrial, anti-intellectual thrust of my program, which like most film production programs, taught rhetorical conventions and rewarded synthesis. I wouldn’t have made it through my BFA if not for an experimental film history course taught by Izabella Pruska-Oldenhof, where I saw for the first time many things that left a deep impression on me — The Art of Worldly Wisdom (55 minutes 1979), The Road Ended at the Beach (33 minutes 1983), Otherwise Unexplained Fires (14 minutes 1976), Rose Hobart (19 minutes 1936).

My work had two births, first, the life I came up through in the stacks of my parents’ library, further illustrated by late night movie shows like Off-Beat Cinema and the Showcase Revue, and the golden age Hollywood mainstream of TVO’s Saturday Night at the Movies; and second, after being demoralized through the course of my BFA, I turned back to underground film and started to restore and preserve rare films, starting with John Hofsess’s Palace of Pleasure (38 minutes 1966/67) and Peter Rowe’s Buffalo Airport Visions (19 minutes 1967). That kind of involvement with underground film reawakened and expanded my beliefs. By 2008, I had come to Ryerson to do my PhD, and I reconnected with Izabella and I met Bruce Elder, and they made it possible for me to return to this kind of filmmaking by providing a supportive environment, and in Bruce’s case especially, by giving me the lore of the tribe and reigniting my convictions. I realized very quickly after I started making films again, around 2011, that it was a nourishing, spiritually sustaining activity for me. It made me largely immune from the isolation that most graduate students feel, it rebuilt my confidence, and it kept me focused on the creation of real objects, so it had a practical role in my wellbeing.

Mike: Could you say a little more about Bruce Elder’s role in your artistic second life? And dish some of “the lore of the tribe?” Have you drawn inspiration from his massive body of work, the prodigious The Book of all the Dead (1975-1994) which encompasses some 40 hours of film? Were you ever concerned about drowning in all that emulsion, that it might be too much to absorb while still being able to feel your own aesthetic leanings?

Stephen: In the time that I’ve known Bruce, he’s been writing this remarkable series of books on early modern movements in cinema, so, by our friendship, my awareness of the roots of experimental film has expanded beyond what I could even have hoped for. There’s not much to dish, just a lot of lost and vanishing histories. My dissertation was a historical one, with no practical component, so Bruce’s role in my filmmaking has been as an ally and an inspiration — he’s simply always encouraged me in any directions that I’ve chosen.

I have drawn inspiration from The Book of All the Dead, and from The Book of Praise, which encompasses his work since. I recently began to preserve Bruce’s films, which is a substantial task, but one which I hope will introduce his work to an entire generation of filmmakers who may not have had an opportunity to see it. I’ve never really felt inhibited by the weight of Bruce’s work. I find his films endlessly fascinating, and I also accept that they hold a strong aesthetic disposition toward density, which only increases the respect I have for them. I would gladly drown in that emulsion, and let so much of it fly over my head without embarrassment. There’s a genuine adventure in taking on work which astonishes, troubles and surprises you, and I believe that the value of an artwork is in its ability to remain mysterious even through many visits. I won’t claim to be the code breaker of Bruce’s films — much of it may set beyond my comprehension — but each time that I’ve seen Lamentations (7.25 hours 1985) or Consolations (11 hours 1988) or the Exultations, I see something new. Sometimes it feeds my fascination as a historian; sometimes it inspires my work as an artist; but it always makes me feel satisfied and enriched for having experienced it. So while my work doesn’t strongly resemble Bruce’s, in many ways it issues from his influence.

Mike: Bruce has been a central figure for the Loop Collective. Could you talk about the Collective’s origins, why did it start, who is engaged, and how are you involved? I realize artists can be reluctant to admit to belonging to an affinity group larger than one, but in broad strokes, are there shared dreams, approaches, or themes that the group draws on?

Stephen: The Loop Collective was founded by a group of Toronto filmmakers in 1996, primarily Izabella Pruska-Oldenhof and Jai Sarin, who were students at Ryerson, well before my time. They were students of Bruce’s. It started as a mutually supportive community of young artists, and also as a forum for public programs of experimental films. They would show each other’s work at a time when others in the city wouldn’t, though for the most part they showed a lot of important historical film programs. I was invited to join by Izabella before I was really a filmmaker, because of my interest in history and preservation. My entry into Loop came after their heyday of doing collaborative projects, so my experience of it has been as a group of friends who share their work and screen together. At the time I had attended a number of screenings that I have visceral memories of —programs of Paul Sharits, Ed Emshwiller, David Rimmer, Snow’s Rameau’s Nephew (4.5 hours 1974) and Barbara Rubin’s Christmas on Earth (29 minutes 1963). By that time Dan Browne was especially active in staging screenings.

Dan and I did a two-person show at Ryerson’s IMA Gallery in 2013 around the theme of superimposition — we both use superimposition extensively but to different ends. Through the course of that show a lot of other aspects of our work showed a real consonance. Sometimes Dan works with personal history and experience, as in his Memento Mori (29 minutes 2012), and sometimes I work with collapsing decades or centuries, as in the Spirits Series, but we’re both interested in the relation of past and present, and with elemental and cosmic concerns. We’re both marching through history with slightly different scopes. There are other basic aesthetic sympathies — the use of light and colour — that comes out of a common sensibility.

Izabella’s films are a primary influence, in particular, Scintillating Flesh (4.5 minutes 2003), Echo (9 minutes 2007), and the recent Font Màgica (6.5 minutes 2015). There are methods I’ve been introduced to by Izabella, such as the creation of film-video hybrids, work that exists between media. When I teach re-photography and video-film migration, I usually throw in Bruce, Al Razutis, and Aldo Tambellini, but I caught wind of those strategies first from Izabella. But that’s just technique, and Izabella’s work reaches me on a more perceptual level. There’s something very fragile about the wisps of colour in her fugitive l(i)ght (9 minutes 2005). And some of her work has a kind of video plastique quality — the image in constant flux with few breaks — which was something that I had never really thought about, that kind of sustained trance. Ultimately what moves me about her work and what has lit me a good path to follow, is its sensual mystery, the complexity of a film like Echo, where a song becomes a portal for her childhood, the elevation of a simple binary as in The Garden of Earthly Delights (8 minutes 2008) where flesh and flora alternate. I find her commitment to phenomenal mysteries inspiring.

Mike: You’ve made a prodigious number of films, and alongside them a few videos, including the luminous Hang Twelve (24:19, 2014). Hang Twelve is a formalist’s group selfie. There are theme and variations in a single room, as friends pal around with colour filters, recalling Mike Snow’s Wavelength and the fundamental Snow proposition: that film is made of coloured light. But in your movie there is so much playtime. It’s as if one could make a life out of equal parts formal experimentation and play, or that the creation of art and friendship are inseparable. It’s a very hopeful, nearly utopian project. I’m wondering if you could speak about the differences between your films and videos?

Stephen: There are many overlaps in what I do between film and video, partly because I’ve always used video. Christ Church – Saint James started life as video. I’ve used digital intermediates on almost all film works for the last four years. But there is a distinction between those works that started and remain on video, and those that have gone to, or gone back to, Super 8 and 16mm.

The videos started in the spring of 2013 with Pepper’s Ghost (18.5 minutes 2013). So much of my filmmaking is proudly solitary, but I liked the idea of making work out of shared experience and collaboration, and I wanted to surrender that kind of trust to my friends, Eva Kolcze and Cameron Moneo, knowing that we could build something together that could be a portrait of us, knowing that they would be as spontaneously brilliant on-camera as I knew them to be off-camera. With Pepper’s Ghost we wanted to make something that was as much about us as it was about glass and light. A perceptual enigma becomes much more interesting when you turn to the person next to you and say, “Hey, do you see that too?” Hang Twelve continues in that spirit, and it has idiosyncratic, referential details to it, fixating on multiplication and anagrams. The process turns those details from a personal neurosis to a shared pathway. These works were meant to remain open to improvisation, play, love. I reject the idea that modern forms and authorship are incompatible with play.

These social, performative pieces have slowed a bit in the past few years, but I’m trying to do a couple of them right now. I’ve been writing charts for new pieces, and doing sketches for a longer video in that style. I’ve also made a few with my students, but those are always sketches and lessons. There’s a threat in overthinking and over-planning something like a chart for improvisers, so I take it slow.

Snow’s aesthetics have been a strong influence on my video work, so much so that I made one piece entirely in tribute to him, Variations on a Theme by Michael Snow (7.5 minutes 2015). Those themes are, among others, the demarcated frame, serial repetition, the flexing, shuffling horizon. I also think that playtime is a big part of what he’s doing in some of his films. I think that there’s been something of a misunderstanding around Michael’s process, maybe spread by people who haven’t watched the films, or who see in them only rigid concepts, closed to improvisation. There’s an incredible degree of play and improvisation in Michael’s films, in Back and Forth (52 minutes 1969) in *Corpus Callosum (93 minutes 2002). Rameau’s Nephew is wall-to-wall playtime, and it is social and improvisatory. It’s the work of an artist who trusts that reality will remain interesting if you populate it with enough people and obstacles.

Hang Twelve was shot in my apartment near Eglinton and Mt. Pleasant, where I’ve lived since 2008. Over the course of about ten hours, five of us (myself, Eva Kolcze, Emmalyne Laurin, Cameron Moneo, and Blake Williams) built frames out of coloured painters’ tape, trying to keep it taut, as a way of marking the frame boundaries of the video camera, as the frame drew nearer to the windows. The frames remained in place as we moved inward. The boundaries were determined by a gradually rising focal length calculated using the twelve times table — the first shot is on a 12mm lens, the last is on a 144mm lens — so you see the space move from wide to telephoto distortion. There are twelve stations. Each station is divided by a sequence of solid colours built from a 12-slice colour wheel. By the final few stations, we had to apply the tape directly to the windows, so it went from three to two-dimensions. At the last station, I sit down and read a poem, then I walk out onto the balcony and throw a bucket of water at the window. After that, we see the whole construct in colour negative, with the colour wheel sequence in colour negative as well.

Hang Twelve is built around references to structural film history and art history — the title is an anagram of Wavelength, and the central action is a nod to Wavelength. There are things that are concealed by all of the visual noise of our construction — I keep holding up or showing in other ways a small reproduction of Salvador Dalí’s Christ of Saint John of the Cross, one of the great works of enigmatic perspective. The poem that I read at the end is made up of anagrams of Ernie Gehr’s Serene Velocity. I was working from a series of charts that laid out the details of the action, and I had particular ideas about what I would do at certain stations, but I didn’t want to guide the actions of the others, so I kept most of it to myself. I also figured that, by constructing this tunnel of tape, what we were making was unpredictable. Sure enough, you see it sagging, and you see a lot of frustration from us at different points. But we didn’t let that overshadow our fun.

Mike: The “difficult pleasures” (as you once put it) of movie poetry return in your 16mm Spirits trilogy: Christ Church – Saint James (7 minutes 2011), Spirits in Season (12 minutes 2013) and Brébeuf (10 minutes 2012). Each features a hauntology of gestures, a return to ghost landscapes and architectures that are re-animated through overlays of pictures and colours. So many moments appear as archaeologies of memory, as if it were no longer possible to relate a solitary instance of seeing, only relationships. In your hands the picture plane becomes an intersection, a crossroads, a meeting place. Can you talk about how you achieve your phantasmagoric layerings, how you came to these specific locations and what meanings they hold for you?

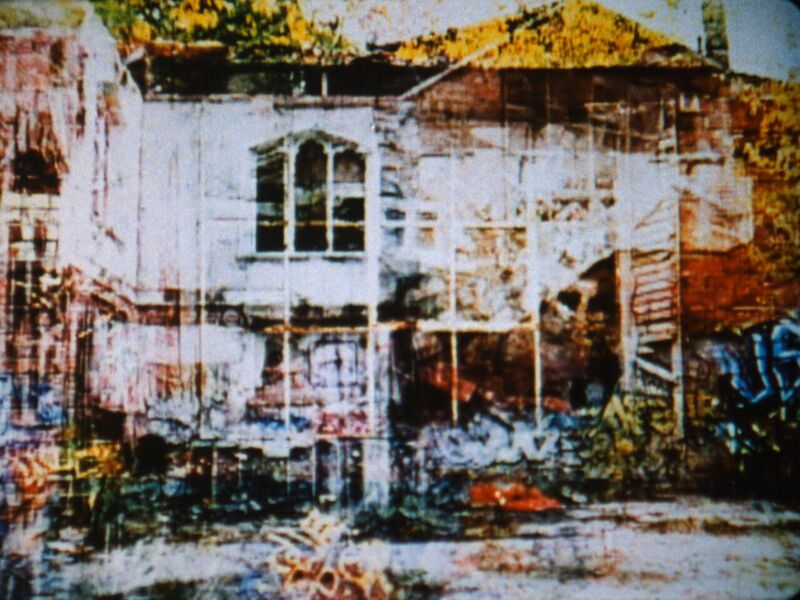

Stephen: The ruins of Christ Church – Saint James stood near Ossington and College for many years after the fire that made them. The arson, which took place in the spring of 1998, was believed to have been caused by a prominent member of the church, Stephen Toussaint. It was discovered the next morning that he had killed a co-worker earlier that night, and vanished, his body was found a year later near the Scarborough bluffs. I think of the film as being something like a memorial to the church, its congregation, and to this tragic figure, whose guilt in the arson remains ambiguous, but if true, suggests an attempt on his part to destroy everything by which he had defined himself — in particular, his family and his black identity. The church was home to a British Methodist Episcopal congregation primarily comprised of Caribbean immigrants. Toussaint himself was from Grenada. His motive for committing such a crime remains elusive. He’s a man with no history of violence, suddenly implicated in the murder of his friend and arson in his community. I found the story haunting, and I set out around 2005 to film the ruins, while they still stood. That footage sat around for several years until I started to work with it again, with fresh eyes, around 2010, and eventually took on the approach you see in the final film, where the image, which was originally video, was layered using optical printing, combining scenes re-photographed from video to 16mm with scenes blow up from super 8 to 16mm. I take what I am doing in this work to be a kind of programme filmmaking, in the sense of programme music, filmmaking that draws on narrative but finds voice as abstraction and improvisation in the present moment.

The second film in this style, Brébeuf, comes out of time I spent in Penetanguishene, Ontario, and in nearby Midland, Ontario, where the story of the Jesuit martyr-saints Jean de Brébeuf and Gabriel Lalemant has settled as a kind of founding myth of New France. The missionaries were involved in the struggle between the Huron and the Iroquois, and, so the story goes, were caught by the Iroquois and tortured to death, including a kind of mock-baptism with boiling water poured over the missionaries’ heads. The film was shot at two sites of significance to Brébeuf — the Jesuit camp, Ste. Marie Among the Hurons, and a field in Tay, Ontario, believed to be the site of his martyrdom. Where Christ Church – Saint James dealt with alienation and otherness, Brébeuf bears duty and suffering. Toussaint gave the most violent flight he could; the Jesuits died by their convictions. I’m overcome with a great empathy for both Toussaint and Brébeuf, but I also think we can’t know the truth of their stories or distill them to any one meaning or theme. We know no more about Toussaint’s dark night of the soul, which happened less than 20 years ago, than we do about Jean de Brébeuf and Gabriel Lalemant’s execution that happened 367 years ago. But these aren’t films about historical insight, they’re about the experience of being in the present.

In making Spirits in Season, I drew from the story of the Fox sisters, mothers of American Spiritualism, publicly exposed as frauds in 1888. The film was made at Lily Dale Assembly, the heartland of American Spiritualism, a village in upstate New York, much of it on the former site occupied by the Fox sisters’ cottage, which was moved there around 1915. Lily Dale has become the central pilgrimage site for Spiritualists, but contrary to the title of the film, I made it there “off season,” in the fall. And it was less tied to the sisters’ disgrace than to the strange character of the place itself — the stump of prayer, the fairy path. By having this as the final work in this small cycle, it tied the whole project to the seasons, with Christ Church – Saint James as spring and summer, Brébeuf as winter, Spirits in Season as fall. All of this storytelling is a bit tangential, an occasion for making a film and something to think about while moving in and out of the trance of gathering images. I think what struck me about each of these places when I visited them was what a great silence had come to settle in them.

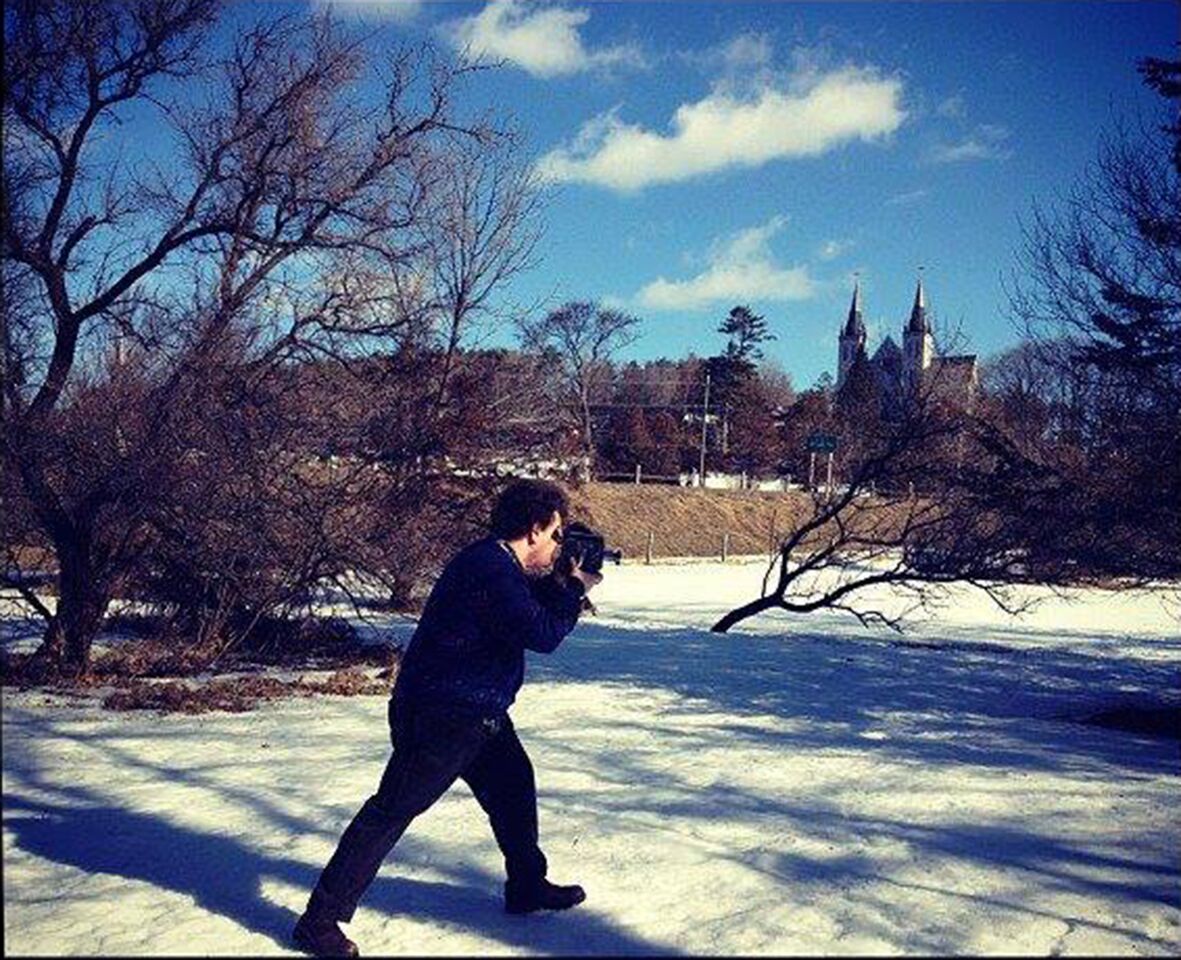

I’ve made a few other films that take on this programmatic root, for instance, Zerah’s Gift (7:36 2013), made while thinking about Zerah Colburn, a human calculator who lost his gift as he grew older, which I shot in the land he was born in and where he later came to die, in Cabot, Vermont. Every one of these films, in the Spirits series and beyond, draw from a heap of fictions, rumours, and dimly-charted histories. I’ve been criticized for being obscurantist — I don’t care that it’s obscurantist because I don’t think the work is closed off as an experience by whether one knows this dimension of it or not.

Mike: I wonder if you could spare a few more words about “programme filmmaking?” I’ve never heard of it. Perhaps you could cite some examples (or are you a school of one?) and any other traits it might possess, or lineages that it recoups and replays…

Stephen: Oh, I don’t think I’m a school of one, we’re legion, but I hesitate to name too many others because I wouldn’t want to oversimplify what anyone else is doing. It’s not the only thing going on in these films, but it’s one of the themes that we see enacted in a great deal of underground film. The idea of programme music as applied to cinema isn’t necessarily a commonplace. With the Spirits Series, I’ve tried to build something abstract and experiential, something that doesn’t eschew improvisation, fashioned out of reflections on a past to which I could not bear witness. And the past tends to be understood as narrative, especially when given to us as authoritative history. When I look at Brakhage’s Visions in Meditation (4-part series, 1989-90) I see them arising from a similar sensibility, as they draw from figures and events that are past, re-articulated in his reflecting. This isn’t to draw away from other influences, like his debts to Gertrude Stein, and I don’t mean this as an affront to Brakhage, who had strong beliefs against conflating what he was doing to narrative forms — but it is an aspect of those films, especially Visions in Meditation #2: Mesa Verde (16:22 minutes 1989). The romantic titling of many of his films, and particularly his painted films, draw from such myths and fables. But that’s a looser notion of “narrative” than a lot of people might have. Programme music has a more traditional, storied sense of narrative, as in Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique (1830), whose accompanying text turns the whole piece into an episodic confessional. I draw from these ideas because those figures and histories help to shape my instincts in an environment, and because these stories, which are full of moral conflict and ambiguity, assist the work in remaining open to meaning.

Mike: I think I hear you transposing a trope of classical music and applying it to fringe media. Programme music, crudely put, “illustrates a story,” or converts story elements into music, and finds its heyday in the romantic period, though it features in the music for Star Wars (1977), or Disney’s Fantasia (1940). Fascinating to hear you dish it as an underlay for underground visionaries. Brakhage was of course a great myth-maker, while he struggled mightily to convey the sense of a becoming-present in his camera work, this present was often unveiled as a procession of synecdoches, parts that reveal a whole, and that wholeness, or inter-being, feels both autobiographical and cosmological. Dog Star Man.

Many of your movies feature site encounters, which you energize with sometimes vigorous camera gestures, miming saccadic eye movement perhaps? Serena Gundy (3:32 2014) is a deft and lyrical portrait of a forest, often conjured in multiple perspectives, as if one could never encounter a single forest, but only a series of forests in time, and that the time of the forest’s namesake, and this time now, needed to be read together. I saw these superimpositions as temporal maps that continually shifted the view of the present, flickering back and forth between then and now. Like your Spirits trilogy, the gestural camerawork conjures a sense of an embodied present, even as the post-production layering evokes ghost stories.

Stephen: The gestures are less miming the eye than feeling out the place and introducing the camera as an extension of body and presence. If there’s a vigour to them, that’s me, and if there’s an anxiety to them, that’s me as well. I follow in the steps of others in wanting the camera to approximate my nervous system, and I think a lot of the more casual movements in the films are the result of breathing. The most violent movements have some connection to the roving of an eye, but I’m also stretching and straining my body in the space, which allows me to occupy those environments in a way that is different from the cold calculation of looking at a landscape and rendering it. The Landform films take this idea to an extreme, but it’s a theme throughout the films, especially in Serena Gundy.

The idea you’ve struck on about the shuttling of past and present is something I’m very glad to have recognized in what I’m doing with that film. I spent a great deal of time in that park as a child, so when I watch that film, I see it riddled with ghosts of personal memory, masked in ghosts of public memory, for instance those for whom we name civic monuments, who become increasingly obscure by the distances of time. The namesake is as simple as a misheard rhyme. The relation between the camera and the body is one that I struggle to think through because there’s a part of me that regards its inscriptive abilities as an absolute extension of my body, and yet, I am also inclined to treat the camera, as many structural filmmakers do, as a constructive tool, as distinct from the organism as it is indifferent to the vision put before it. But when I make a film, I want to stay those doubts, to work from instinct, with a basic trust in the instrument, and that the actions I’m engaged in will be a faithful rendering of my experience. I think this approach makes the work intimate. If Serena Gundy is a spooky film, that may be in part because the image is wavering as if projected on a hanging sheet, an effect gathered incidentally by using an inferior telecine machine, another accent to the spectral combines of positive and negative images. It was composited and put back to film in this way, by intention.

Mike: Jenny Haniver (15 min 2014) features ten decomposed film portraits of Jenny, a study in serial approaches. How to separate figure and ground, the means from the face? Who is Jenny, and why so many lookings?

Stephen: I don’t think of those portraits as decomposed, I think of them as being transformed, abstracted, made into something new. I know that the language advanced around these kinds of techniques has shifted somewhat from alchemy to apocalypse, but I think it’s more a revealing of artifice than a violent act against the thing itself. There are ten portraits, each of a different subject, each subject a woman. The film’s title is a misdirection, as was Serena Gundy, here the name was contrived not from a person but from a thing. A Jenny Haniver is an ancient totem that has been dried and refigured into the shape of a mythical creature, carved so that it resembles a creature with legs and arms, a devil or a dragon or a particularly menacing angel. We could say that it’s a holy talisman for sailors, but whatever it may once have been, now it’s just a tchotchke. One of these critters turns up in Hollis Frampton’s ADSVMVS ABSVMVS photo series, though he referred to it as Chimaera (Challorhynchus capensis). And it’s not really the faces of the subjects that mirror this totem, but the film object itself. The reel becomes Jenny Haniver, its stamped-out reproductions cut into the shape of something new. The photo-inscription may seem fragile through the course of this, as it’s washed away in veils, bleached and softened and etched away. But it is only the image, the representation, that is fragile; the subject, and by extension reality, endures.

Mike: Bridge 1c (1:05 2015) features a dance of geometries and architectures, granting liveliness through a new foundation of impermanence. It’s a subjective reimagining of waiting at a street corner, here is evidence of a mind wandering, setting the whole city into motion. A manifesto of anti-stillness. A demonstration of how everything apparently solid is forever changing.

Stephen: The Bridges are all strongly related to the themes that you’ve presented here, they are films about nature, architecture and transformation. They’re sketches, in a sense; their role in my programs has been to serve as light dividers between other works. I’d like to take on your question first from the perspective of Toronto. I’ve witnessed its changes over the past three decades, and the resonances its newest architectures find with its earliest surviving forms. It is a city of ravines, where the confrontation we feel with nature is engineered against the roads. A big part of that confrontation is in the ways we’ve expressed dominance over nature by building up and through it — by sealing in parklands with a loose web of concrete and glass. With Bridge 1C you see an imagining from a street corner, in the empty backs of signs, absolutely, and you see gulls on parking lot lamplights, and circular movements over scenes from the Don River, and by the collisions of these circular motions, gathered by a mind wandering, there emerges a new geometry to the city, one that encloses the natural and manmade, an experience which is also at play with building blocks of colour — red, yellow, blue.

Another thing that is going on in Bridge 1C, and in many of the other films, is a play of transparency, which I think is a resistance to those rigid architectures that stay the dance. By rendering it as image, even a concrete building can become porous, opened to communion with most any other thing, able to pick up affiliations of meaning, to be transformed. In that sense filmmaking becomes an act of carving trenches out of light and filling voids, moving away from the density of real things toward the more pliable forms of memory and dream. I know that makes for busy artmaking, but the days are often filled with crowded and simultaneous experience.

Mike: In describing Landform 1 (2.5 minutes 2015) you wrote: “To be present in a landscape is to turn from vision to a menacing rhythm.” Is it menacing because our seeing too often separates and objectifies, while you are practicing seeing “with the whole body,” opening to new joys and terrors? Or because there is a tension between the moments of shooting and the edit/shaping that comes after?

Stephen: My presence in any environment, as far as I myself am aware of it, is something I understand visually and by vision-knowledge remembered. But this work, which was entirely made by enacting violent physical gestures with the camera, is almost totally non-objective. It would be hard to recognize a landscape in these images, for the most part. I think of their abstraction, by motion-blurs, as a transcription of my physical presence and experience in that landscape, wildly straining, tossing the camera, to exhaustion. This film is not a disavowal of vision but an event. It turns away from legible vision, with a camera that is an extension of the eye, and instead offers vision as a consequence of movement. That movement is a menacing rhythm, a rhythm that takes precedence over the senses.

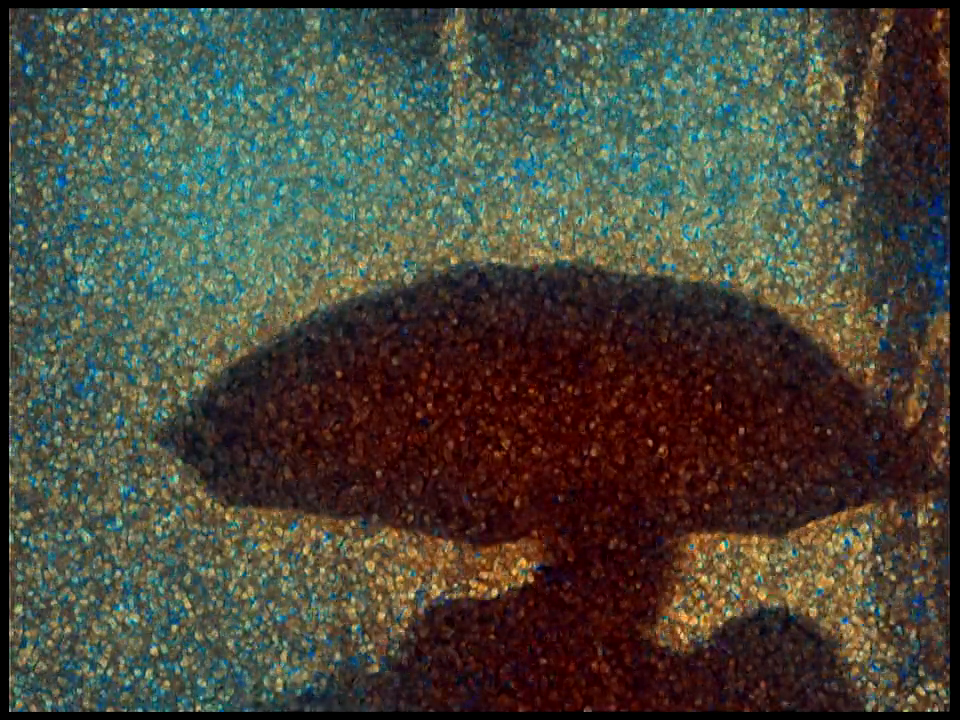

In terms of the distance between shooting and shaping, the landforms go through tinting and toning baths, a process that gives them unnatural colours, made more unnatural by digital enhancement. This is another strategy to mark the work as squarely non-objective. I don’t see that aspect of labour in terms of tension, only pleasure. It also brings the film into a dialogue, I hope, with the work I was most thinking of when I made it, Helen Frankenthaler’s soak-stain paintings and Clyfford Still’s paintings, in particular, his PH-401. I’m proud of the resemblance. The other parts of this series, which I’ve not yet issued, use different tones and tints, and host other gestures and rhythms, but are likewise works of presence and experience, against representation.

Mike: You wrote: “In many of my films, reality, if we may call it that, the reality of the recorded experience, of perception, is hammered down, wrecked, above all obscured, through processes — these happen to be digital processes, primarily, but they might be any processes that treat the recorded moment as something transformable. Sometimes this process arises from joy, sometimes from rage and grief. By the time that process begins, the original experience is already passed. Concealing it makes it new.”

It’s an amazing description of how movies might be made. From the wreckage arises something new. I hear something about the necessity of violence here, the importance of transformation, perhaps even the revenge that underlies representation itself. The energy of this anger is also the necessary energy of creation, and the grail of newness is achieved only by concealing a history of (joyful or grief-stricken) wreckage and censorship.

Can you talk about the place of anger in your practice, and wreckage, and how this might relate to your camera work, and the importance of “obscuring processes?”

Stephen: Wreckage can mean a lot of things. I think of destruction as the necessary path of transformation in any plastic art. In my work I would define violence as those blunt acts that refigure the image, or that force associations, or at its most general, anything that resists realism, that acts against plain and unenhanced photographic representation. Sometimes I’ve embraced literal wreckage, as in Jenny Haniver, where the emulsion is loosened then smudged by fingertips and sheared by razors. Most usually, the wreckage is a piling up of moments upon moments, a crushing of events and perceptions into something new by digital compositing, or even, and this is pretty common in the work, an of-the-moment abstraction of reality by motion blurs; unnatural, angular compositions and anamorphosis. My operations in making a film aren’t clinical or coolly detached. These are confrontations with the world, wonders and terrors and all.

I like that you describe it in terms of energy, because that’s how I think of these things. I should just clarify that I don’t feel that my camera work is a metaphor. The Bolex is a tool for confronting and reflecting the world, and I use it in earnest. I don’t believe that when I spin with the camera, when I pitch the camera, that the resulting fluctuating movement is analogous to any particular feeling, or at least, to anything that would be just as easily said. These are expressions of energies, and sometimes those energies are heavy with grief and anger, as in the Spirits series, and sometimes they are light with joy and pleasure, as in the Bridges, but the expression arises from energy and not from temper. And sometimes these aspects of my camera work are just a functional means of looking at or around or through a subject.

I’ve come to feel that these processes, the digital compositing and camera gestures, allow the subject to reveal itself in spite of my will, and that by working out of honest fascination the work will open to and admit mysteries. I follow the path of modernism that asks artists to surrender to the audience the burden and creation of meaning. My processes obscure experience and perception, obscure in the sense that the work becomes alienated from its root source, and thereby, from its simplest meaning. By my obscuring gestures, I am not prescribing an experience to you through my work. Instead we are collaborating on a mystery.