I Felt Like an Octopus: an interview with Madi Piller (October 2016)

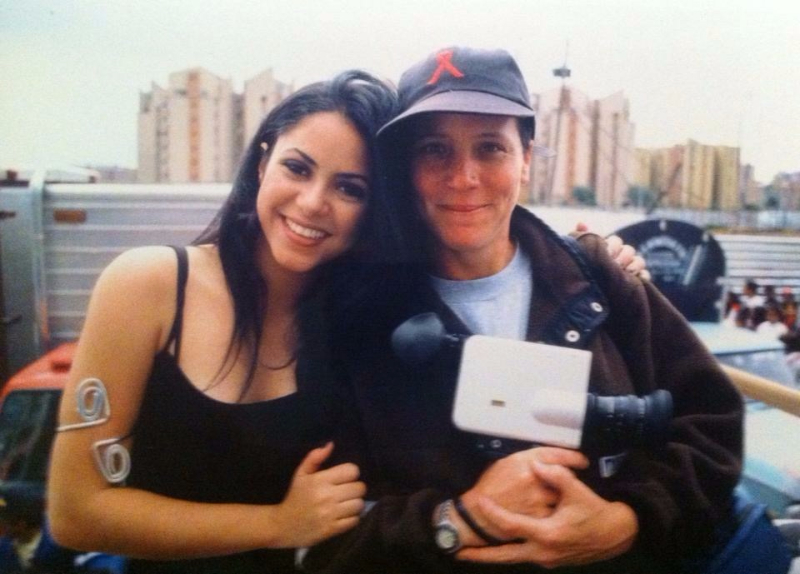

Mike: One of your earliest movies was shot on super 8 in Columbia and features pop phenom Shakira.

Madi: I was working as the producer at a large ad agency. An opportunity came up to make a TV commercial with Shakira. The creative department’s idea was to mimic a music video that U2 did when they played on a flatbed truck that drove through the streets of New York (“All Because of You,” November 2004). The soda company in Colombia had already contacted Shakira who was a sensation at that time, though not as famous as she is now. The company paid her to write and perform a song for their soda pop.

The commission went to a director who is a big name in Colombia. But the creative director in the agency hated the idea of shooting with him because he was too straightforward cinematographically, and we wanted to achieve something fresh, in the style of a music video. I said don’t worry, I’ll bring my super 8 camera and shoot. So while the “real” director worked, I ran around shooting my version of the commercial. Mostly they used my footage because the official footage was too clean and static. It had no energy, zero. My footage caught the spirit of the street. We didn’t contract the big crowd, only a few people for close-ups. We just started driving through the streets with big speakers, and when people realized that Shakira was in their neighborhood they all came. We had jeeps filled with sodas that were being given away. Who doesn’t like free stuff? In the end we had a mass of people following the truck, while others peeked through their windows to see what was happening. None of that was set up.

Shortly after that Shakira went to the United States and her look changed dramatically. She lost weight, dyed her hair, and became the person she is now. I have a picture of Shakira hugging me. I’m not even looking at her, I’m just holding onto my super 8 camera. My sister likes to tease me: look who is holding you!

It was made in the same spirit as my Caribana film Bacchanal (15 minutes silent 2014 super 8). I like seeing things. When I’m behind the camera I’m looking for the world, opening into the real moments that are happening. Then things start pouring into view. In Bacchanal I wasn’t actually looking for those sexy scenes, but then you start realizing that whenever you pick up your camera sex is happening.

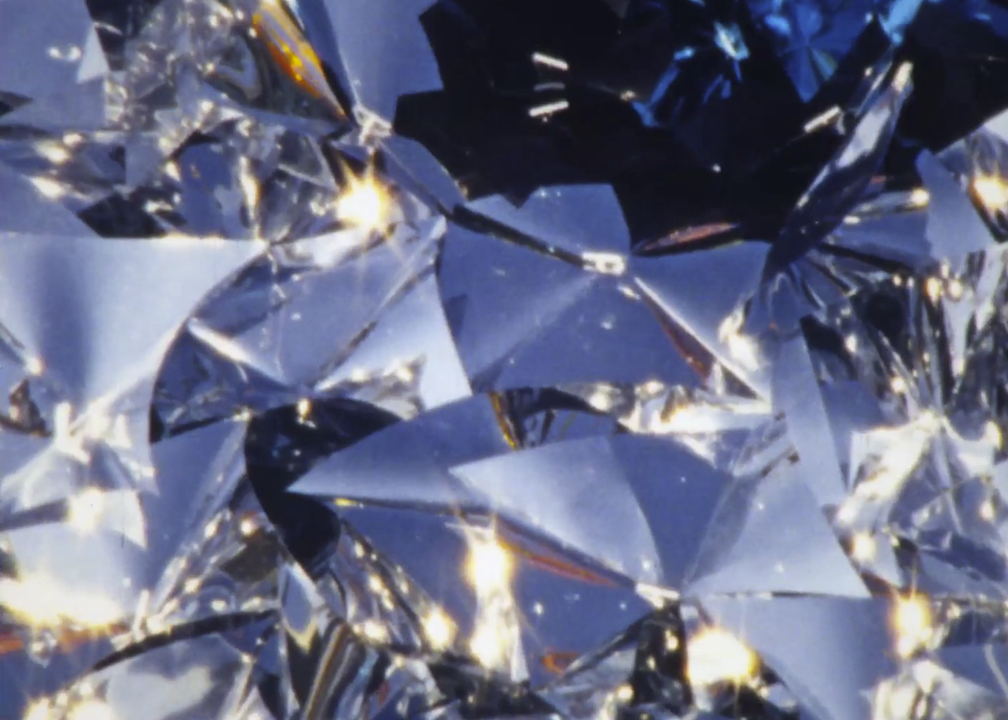

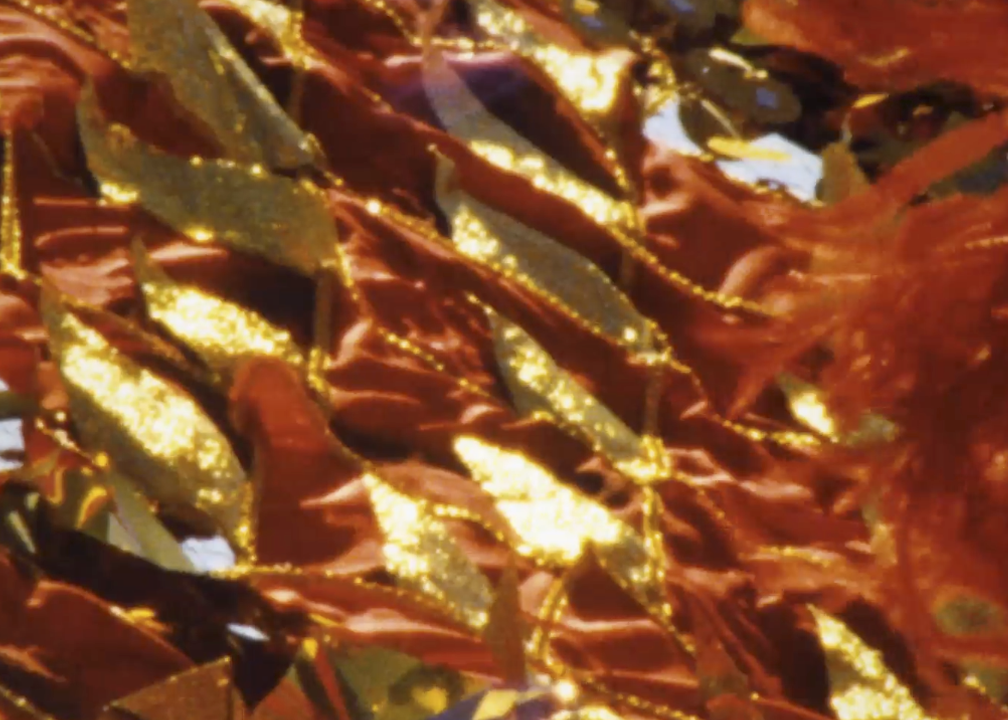

Mike: Bacchanal is a carefully observed study of Toronto’s annual Caribana celebration aka the Toronto Caribbean Carnival. It brings hundreds of (barely) costumed dancers together in a street parade.

Madi: It was a beautiful sunny day, splendid. There were colours that made you want to dance. You could feel the East Indian and Caribbean communities the whole grandiose day. These guys prepare the entire year for this day when they rejoin their communities. Most people buy costumes, and they’re not cheap. The parade is made up of groups, organizers come up with the group theme and commission someone to design the outfits, and each mas band makes costumes. The community comes together for this.

My husband helped a Caribana group that needed a place to build costumes, and he helped them with that. We became close to the group, and were invited to go to the opening party. Later we were offered a ride on the float and I thought hey, that’s a first class seat, I’m going to be able to shoot what’s actually happening during the parade. I was totally enticed by the colours. But as the day went on I saw how some of the crowd was partying.

Mike: Your shooting begins with colour and abstraction, then turns to the dancers, and finally finds dirty dancing at the end.

Madi: It was completely surreal. My camera on the float started discovering the frenzy as the day went on.

Mike: They’re basically having sex in public.

Madi: It is what you see.

Mike: Did it make you think about Toronto differently?

Madi: It reminded me how liberated Toronto Is today and what I heard of Toronto years ago

Mike: When you came to Canada, some of your earliest movies are animated. How did your interest in animation begin?

Madi: I’ve always liked animation, it’s a way of expressing things. You don’t need to wait for anything to happen, you just start creating. When I worked in advertising, you see all the planning that goes into a scene of a family eating, or a guy drinking a soda. You spend three hours to set it up and someone takes a drink and that’s it. You wind up with thirty seconds after two days of filming, it’s ridiculous. But when we did some TV commercials that were animated, I liked the way animators were left to work on their own. You give them instructions and after a few meetings you trust them to bring in what you need. I admired their craft, and the fact that they could work by themselves. That attracted me.

I never tried to do any animation myself when I was producing commercials, but I did shoot a lot of super 8. I remember making a commercial for Clorets with a couple kissing each other. Kissing, kissing, kissing. It won a prize actually. But the client never wanted it shown on TV because there was too much kissing (laughs). I shot it on super 8 with a creative director who gave me the idea. That was in Colombia where I worked for an ad agency from 1992-99. In the final years there I was in transition, living in both Colombia and Canada. I had a Canadian permit to go overseas and work. But you only get this permit for three years, after that I had to decide whether I wanted to stay in Colombia or move to Canada. I decided to come here.

Mike: How did you start working on super 8?

Madi: I was coming to Toronto to visit my family. My twin sister had moved here from Peru and eventually brought my parents. While I was in Colombia I often came to visit them, and also to watch films at the Toronto International Film Festival (now TIFF). The first festival I went to was Hot Docs, which was held in a bar on College Street. Then Splice This! I was encouraged by Margaret from Exclusive Film (were I was developing my Super 8) to submit my work to this festival and that’s how I met Kelly O’Brien and Laura Cowell, the organizers. It was a festival dedicated to super 8 films. I continued coming every year to visit my family but I did not see them much because I was completely immersed in films screenings. I took my holidays specifically during the time to attend the Toronto International Film Festival. I started seeing contemporary films that had more experimental tendencies, not the regular mainstream fare. I was always looking for discoveries in the catalogue, anything that had a description including mentions of “super 8 film” or experimental.

I met my future husband on an airplane. We were pen pals for ten years before we married. On one of my visits to Toronto he gave me a super 8 camera that he had, because I mentioned that I was looking for one. Most of the films I shot in Colombia were made with the first camera that I got from him. It was totally automatic; you couldn’t do anything but a bit of zooming. Later on I bought a Nizo from a pawn shop on Queen East. I had my sister here so I would send my films by mail from Bogota, and she would take them to Margaret at Exclusive Film Lab to get processed. Lili, my sister, was the contact between Colombia and Toronto (laughs). I submitted a film to Splice This! which was accepted, and then I sent another. Those acceptances helped me to continue.

That’s the way I started with super 8, making a lot of mistakes, carrying my camera everywhere, even while doing mountain biking. I went into productions and shot my own takes on the side, trying to figure out my vision of the scene been shot. It was a way of training myself. My job in Colombia was director of production at J. Walter Thompson, a big transnational company. Very fun. I opened a gap so that the people at the agency could think differently about how to make commercials. I experimented with creative processes and relations with TV commercial directors in order to realize the full expression of their vision.

I wanted to work between the two worlds of the creative director of the agency and the director at the production house. Once I had a storyboard I would look for imagery and edit from outtakes, found footage, from other TV commercials, music videos or films. Then I would bring this to the creative director at the ad agency and the TV commercial director and try to design the production with them. In this way I was trying to extract the most from the creative people I was working with. It wasn’t just a question of following a storyboard. I opened the door for many young directors.

Mike: Were there people in Toronto who opened doors for you?

Madi: Roberto Ariganello, the former director of LIFT (Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto) was very inspiring for me. One day I was ready to make Vive Le Film (2:13 minutes 2006) and I arrived at LIFT. I wanted to do a test first, and Roberto showed me how to use the Oxberry animation camera. He gave me a few fast instructions, the way he always used to do. He said to me: Madi, you’re going to be alone on this, so you better learn quickly. I got the tests back from Niagara Custom Lab and prepared my artwork for the film. The day I arrived with all the material to start shooting I learned that Roberto had passed away. He drowned in a swimming accident. He has been in Nova Scotia to deliver film equipment to another film co-op. At that moment I felt terribly sad and remembered his comment and Yes, I was alone with this. Of course I had to continue to make the film.

I worked with pictures that were boiled, optically printed and then painted. There was a craft to making these images, it wasn’t just scratching or drawing on film. For the countdown leader in the film I started bleaching the black and white film, manipulating only part of the image, and then adding paint. I thought of how it would look as an inverted image. If I needed blue, I would paint yellow. The whole thing would be reversed in printing. I made a stamp that read: FILM IS DEAD and another Long Live Film. I stamped the film with bleach, and then applied colour paint. The movie is a memory of all the things I learned from Roberto. He was a connector, an amazing guy.

Mike: He was forever urging people to make films, a vital sponsor of community.

Madi: Totally. I met him at a show at the AGO (Art Gallery of Ontario). I think I asked a question so he came over after and asked if I knew about LIFT and that I should stop by. So I went. At that time I was doing TV commercials for a Toronto company. I had landed the title of technical director because I didn’t speak much English at the time. I had the technical aspect down very well, and I ended up managing the sets and doing the initial editing. Shortly afterwards, and after my initial visits to LIFT and Niagara Custom Lab, and participating in screenings that Sebastjan Hendrickson put on there, my thinking switched completely to the arts. I didn’t want a producer telling me what to do anymore, it was time for me to start doing my own work.

In the same building as LIFT there was TAIS (Toronto Animated Image Society). I went to one of their talks and attended a couple of workshops. I remember going to one of their screenings at the NFB’s John Spotton Cinema, where Marc Glassman was in conversation with animator Paul Driessen. We went for beers afterwards. Patrick Jenkins was there and encouraged me to become part of TAIS, so I started a relationship between the two floors of the building, TAIS and LIFT. Patrick asked me to join the Board, and I’d never been on a board. He opened that door for me. After he left a lot of stuff happened, TAIS seemed doomed to close. But I thought no, an organization could not collapse like that.

My husband was able to get us free space for three years, and I volunteered for more than a decade. I felt I was following the model of Roberto who worked for the community. That is the motivation I brought to TAIS. It’s a production center, and since I was producing all of my adult life, I wanted to see people creating new work. They did not have to be only hardcore animators, but people who could embrace animation within their practice of art. That’s how I met Stephen Andrews. He used to come and punch holes in paper for the animation film he was making. I shot for him and also helped Libby Hague, and many other artists who came through.

I always felt like an octopus, shaking hands with many artists with different animation techniques. I also worked hard to maintain the focus of the organization. A center that embraces all sorts of animations, in analogue or digital forms, and mostly that maintains space for the artist. I always thought we should get into wider community involvements to bring artists into other areas of the city, as a way of spreading the voice of TAIS. Eventually, interested people will come back to the organization and join.

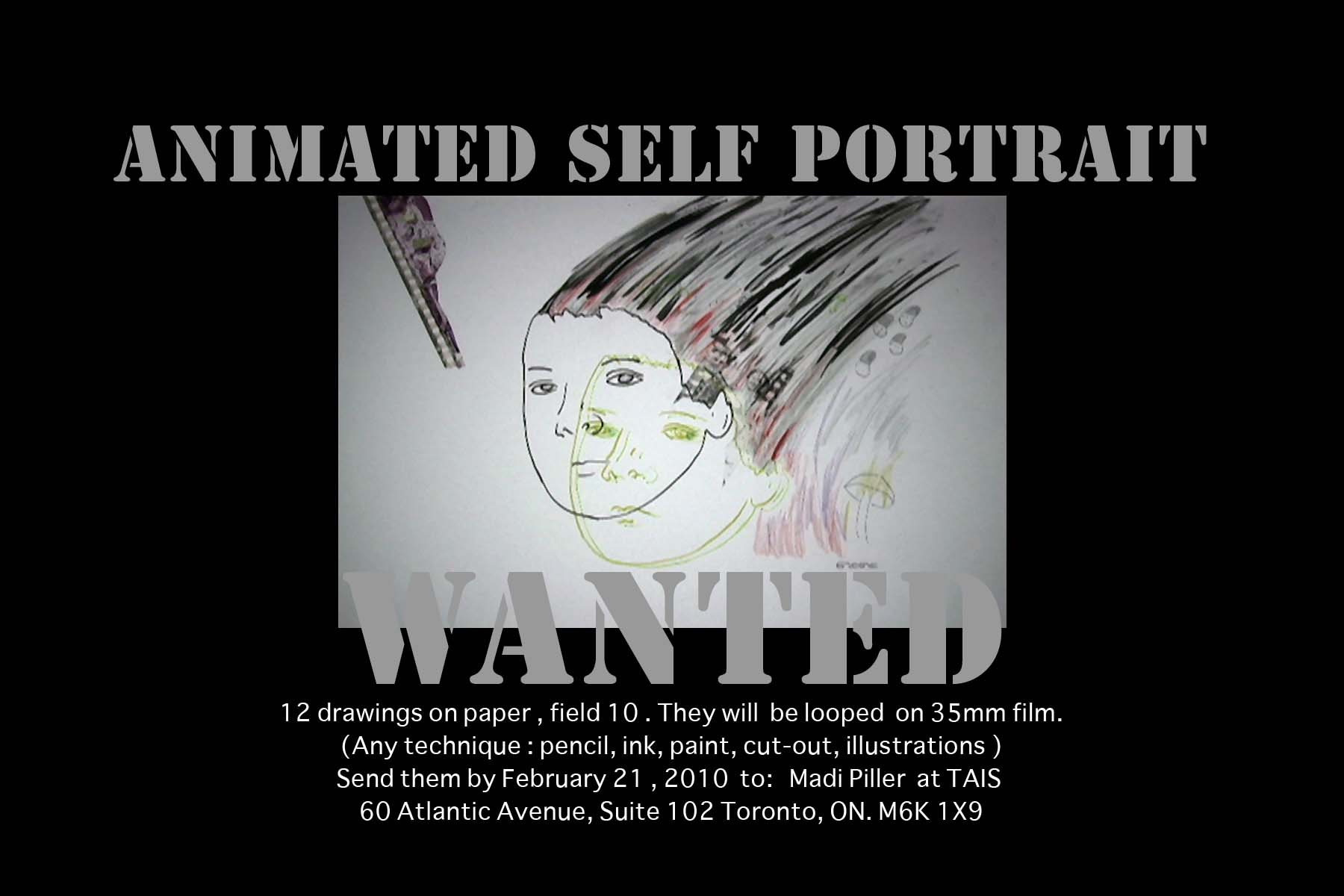

Mike: Your Animated Self-Portraits (8.5 minutes 2012) feels like a community project, an image of community even.

Madi: I asked artists to give me twelve drawings of themselves on paper that I would animate as a loop. Every type of animation appears in the film. At the beginning I thought I would include 35 people, but in the end there were 84. It was shown at the Ottawa International Animation Festival, in the Canadian panorama. People loved it! This is a piece that unites all levels of animators, from experimental to industry to independent to those working with the NFB (National Film Board). The project kept growing and the artwork I received was so nice I knew I had to film it in 35mm. The Canada Council for the Arts supported the project so I shot in 35mm and had a professional sound mix with Dolby.

I asked Martine Chartrand in Montreal, Heather Harkins in Halifax and Gail Noonan in Vancouver to help me get the word out to artists and they were all really helpful. I had so many people, it took much longer to finish; I regret that some people were just tied up on other projects, but wanted to participate.

There needs to be a sequel because believe me there are tons of other artists that are so valuable to our world of animation.

Making the film was part of my commitment to a community of animation artists. It was a way of trying to build bridges between different artists of different backgrounds.

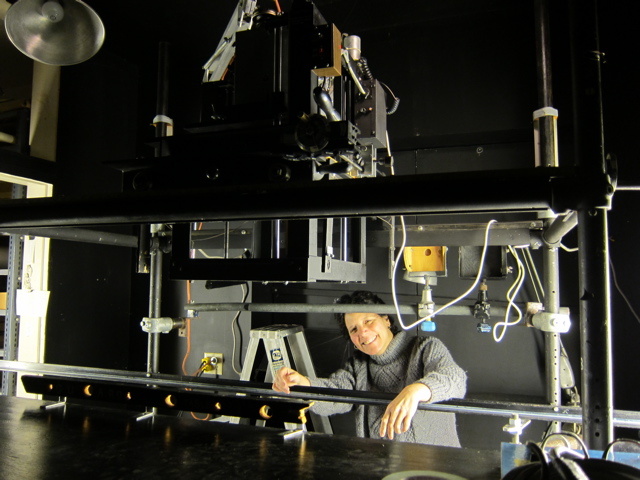

The animation stand I used for Self-Portraits was set up in the living room of Eugene Fedorenko. It replicated the camera stand that Yuri Norstein used on Tale of Tales (29 minutes 1979), one of the best movies ever made. Yuri used a multi-plane camera set up where the glass layers (that you put the artwork on) move up and down, instead of the camera moving vertically. The camera can move left and right, horizontally. When Eugene Fedorenko and Ross Newlove were working on Village of Idiots (12:42 minutes 2008) they wanted to use the multi-plane system with their cut-out animation technique. That’s why they replicated Norstein’s set up, with Eugene’s ingenious, hand-made modifications and additions.

I received many letters from animators, along with their drawings, because some really felt inspired by the project, getting back to analog work again with punch hole paper. Many also offered help, which was nice. Marie-Hélène Tourcotte, Paul Driessen and others, sent detailed dope sheets of how their work had to be shot and animated. Richard Condie wrote: “Thanks so much for the box and stamps. (I gave him a box and return posted stamps for sending his work.) I wanted to put more colours on it, but all my old felt pens are dry.” That killed me. Chris Hinton sent black sunflower seeds to animate on top of his drawings as homework for me. One letter said that this is the last project I’m going to do because I’m growing blind from the light coming from the animation table, and I can’t work any longer. That was hard to receive.

After it was done, I sent to every contributing artist a DVD, and a poster with a list of the artists, so they could all met each other. It was a way of saying we are all in the same boat.

Mike: Can you talk about your animated short Anonymous 1855 – 2005 (1:28 minutes 2005)

Madi: This was a response to media reports about sexuality in the city, you know how the media goes on and on about something, then never talks about it again. It’s about the politics of pornography. Pornography has been around for centuries. There’s nothing new under the sun. Since the 1800s photographs of naked people and prostitutes have circulated. Why not make a film with these Victorian images?

I wanted to be very explicit and found the pictures in a book of nudes. When you see the first woman she appears defiant, strong and certain. She’s the one who is giving pleasure to the guy, more on the dominant side, while the guy just presses her tit. I also like the two girls softly touching. I looked for images showing different situations that are sometimes comedic. Each image is animated with very limited motion. The first image shows a hand combing a woman’s pubic hair, I only animated the hand. The two women touching each other’s heads also have only their hands moving. A girl is whipped by an older lady. I wanted to show the expressivity of the touch, so the girl’s head snaps back.

I like putting numbers in my titles, they provide a frame and context. There’s a direct reference – this is what was happening in the 1800s. Or this film is from 1944. I like these patterns. I remember when I was in school they would talk about an artist, or a literary event, and I always tried to find out what else was happening in history at the same time. I like to situate events on a timeline. That’s montage, no?

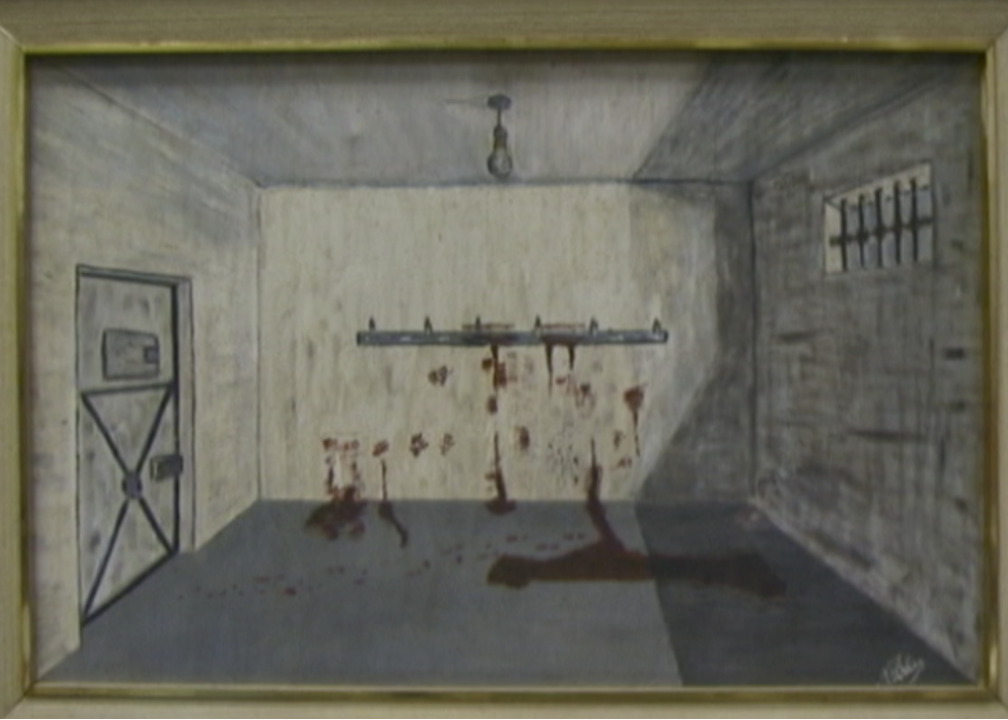

Mike: Can you talk about Chambre de Torture, 1944 (2:29 minutes 2003)

Madi: It began in 1976 when my father was depressed. One day he said to my mother, “I’m going to start painting.” The film shows his first painting: a prison room with blood all around. On the back he wrote, “I vow never to lock a bird in a cage.” My mother said no, if that’s what you’re going to do, I don’t want you to paint. It was a purging of his war trauma. He was fifteen years old when France was occupied. His father had died at the beginning of the war from a disease, and then he was separated from his mother. He went into hiding until he was captured by the French Resistance, labeled as a spy and almost killed. Then another fighter said no, he’s Jewish, he’s in hiding. My father remained with the French Resistance for the rest of the war. He saw too many bad things and never talks about them. He made another horrific painting and then stopped. Now he’s painting again, but only landscapes and beautiful flowers. His house is full of flower paintings. I had to steal his painting of the bloody room. I brought it to my studio and shot it quite quickly on video and mixed it with some super 8 footage that I scratched. I began to compose a film.

Mike: The movie ends with his painting. Was that always the destination, the goal?

Madi: Yes, that’s why I stole the painting from his house. I wanted to make a film about the way my father’s youth was truncated by the war. In the beginning you see small dots in the frame, they could be birds in a cage, or my father playing with friends in a school courtyard. I was thinking about the kind of imagery that might recall regular life for a kid, until you have to go into hiding. I collected images. When I went to Germany for the first time I had goosebumps. This is something my husband doesn’t experience. His family came to North America in the 1800’s, both he and his parents were born in New York. My father only came after the war, so memories are still at the surface, difficult to cope with.

My father’s cousins in Paris, their mother suffered so much during the war. She had a mental breakdown and spent many years in a hospital. It’s difficult for them to forget.

We have new versions of suffering and the refugee crises. The acceptance of these people is still very conflicted, you would think that they would simply be received, that politicians would do better for their own people. That’s why my films are so puzzled by questions of territory.

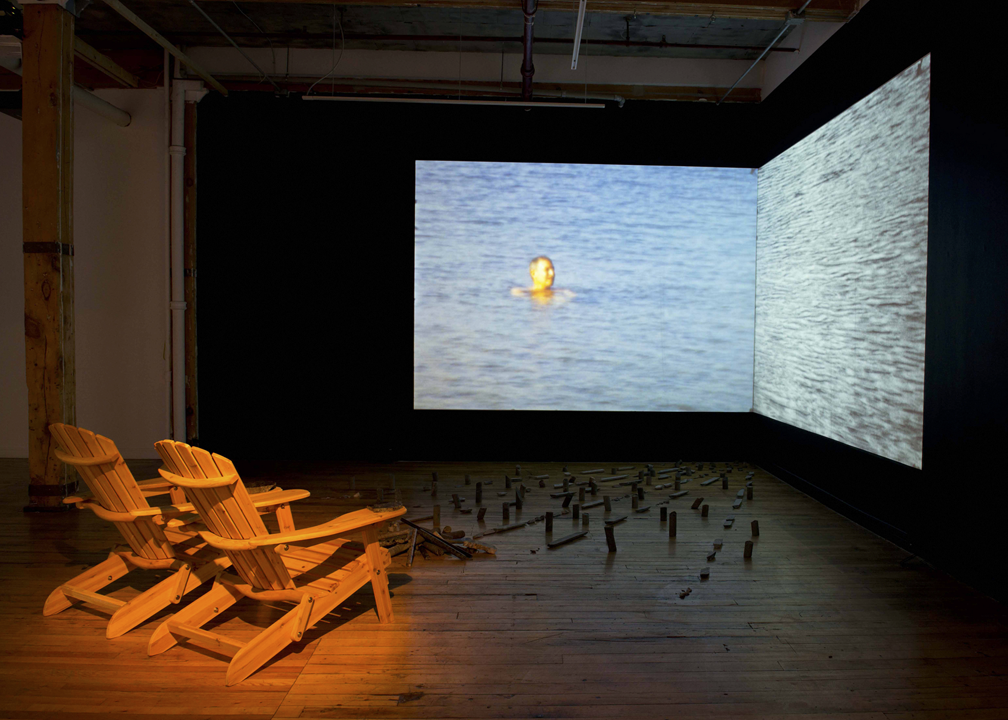

Mike: 7200 Frames Under The Sun (3:20 minutes 2011) is a dual-screen landscape project, sometimes shown as installation, sometimes as single-channel video. It feels related to these questions of territory.

Madi: It has a very light feeling, like a trip to the cottage. But I’m talking about the earth and mining and what people fail to notice. It has two screens, both shot on super 8, and they’re about what we don’t see when we’re in that amazing space. We don’t see the history, the mining of these prehistorical lands.

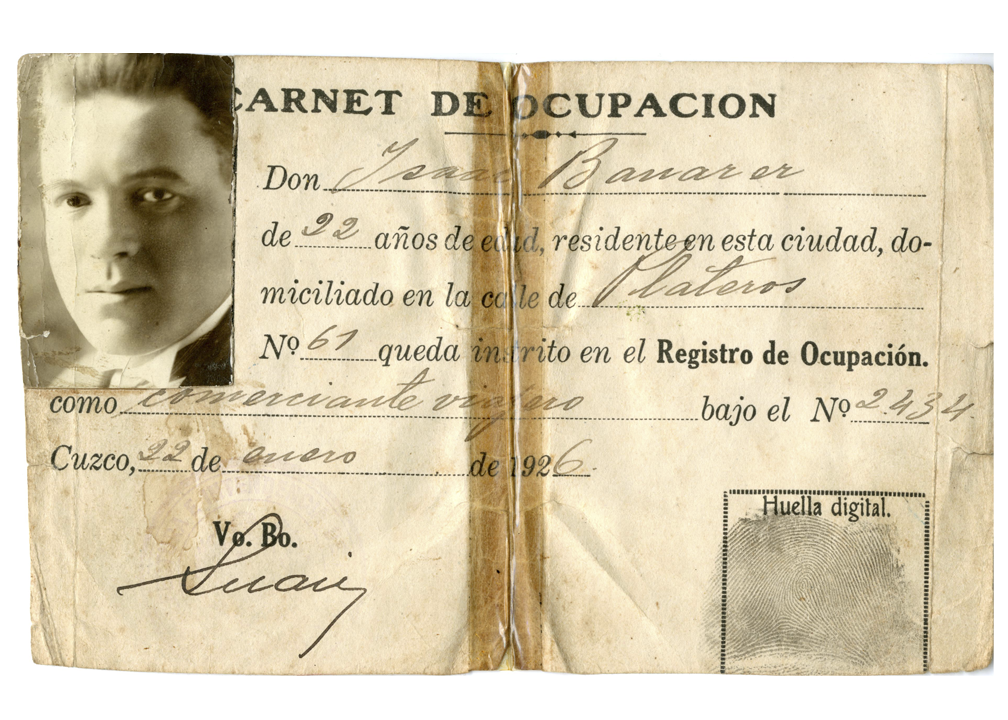

Mike: While you’ve always been a prodigious worker, you’ve been particularly prolific in 2016, completing a number of short projects, along with a trilogy of beautiful, black-and-white movies in Peru called Untitled, 1925.

Madi: I have a poster, Filtrin vs Banarer (Banarer is my grandpa) from 1925 that triggered my Untitled trilogy project. Banarer is my second last name. Madi Piller-Banarer. My grandpa participated in a big international boxing match against Victor Filtrin, an Argentinian, on September 20, 1925 in the Plaza de Toros in Cusco. I went to Cusco, but in the place of the bullring I found a wall at the end of a street, a deteriorated house wall forming a corner, that’s where the bullfighting arena must have been. We explored this adobe wall, trying to pull out its memory and history.

We visited the archives of the newspaper El Sol in Cusco, which was a room full of old newspapers, not even in boxes. Ok, let’s look for something around September 1925. There were no pictures of my grandpa but we found an article written after the match. It says that Filtrin delivered a technical knockout in the fourth round. My grandpa was beaten (laughs). Slowly I realized that Filtrin was a professional boxer (there was a picture of him in the newspaper), a man trying to build up his rankings. My grandpa was just an accessory, the guy who volunteered to fight a professional for some money. I found that beautiful.

I travelled with my husband and Greg Boa, who helped me with filming. I set up the camera frame and Greg would shoot. It was a beautiful way of working together. We both love photography but I have a condition called familial tremor that makes my hands shake. Some days I shake more than others, and you don’t want to go all the way to Peru and rely on your nerves to be steady for the day.

Mike: Did you know when you went to Peru that you would make three films?

Madi: No, I never thought about that. I thought I would shoot a lot, so I brought 2000 feet of black and white, and more rolls of colour. We had so much film but in the end it wasn’t enough. We spooled it down into small boxes of 100’. Going through customs we had rolls in our pockets, all over the place.

Mike: Were you worried about dust?

Madi: No, although you want to have nice clean shots. We had some shots that had marks on the lens, but I used them in a different way. That’s part of filmmaking. Everything was processed at Niagara Custom Lab here in Toronto.

I wanted to make Greg part of the film, he had never gone to South America. I wanted to have somebody with me that wasn’t just a camera person, but who would be discovering a new space, a new land. Seeing through his eyes would help reimagine how my grandpa might have approached these new spaces and travels. How do you face adventure? How do you open your eyes and wonder at the marvelous and terrible things you see along the path? I wanted to share that seeing with him.

When we came back he processed the rolls and gave me all of the negatives which I transferred to digital files. He encouraged me to rework some of the material by step printing on the optical printer, but I didn’t want to add more artifacts to the film. I said I would like to have the Andes footage solarized and he did that. For me solarization brings an aspect of luminescence to the film, a layer of silver that is revealed. Since the Incas, the Andes have been mined for gold and silver. Solarization is about bringing the silver that’s in the image to the surface. We solarized only these parts of the film and it’s used in the second part of the trilogy. The first part Untitled, 1925 Part one (7 minutes 2016) is clean, like a clean slate of black and white, you see the contrast of the black and white, the contrast of the old city and the sea.

In the second film of the trilogy, Untitled, 1925 Part two (8:45 minutes 2016), you see the church against the sky, it’s so imposing, the same way religion and values were imposed. This is the way my grandfather would have regarded these structures. He came from the small town of Bălți in Romania. More than half the population were Jewish, but here every corner has another tremendous church. The churches are as big as mountains.

During his three years in Peru, including the time in Cusco, he became a Peruvian citizen. He was a referee for a boxing match, he appeared in photos with athletes racing on bicycles and locals on motorcycles, and teams of soccer players. It looks like he participated in many different sports so he must have met lots of people in Cusco. I’m learning about him through these pictures. For instance, he never told me he was a boxer. The pictures were probably made by Martin Chambi de Cusco, the most amazing photographer of indigenous people in Cusco. I showed the pictures to his grandson and he said that they must have been taken by his grandfather.

Although I always mention my grandpa as a character in the trilogy, this isn’t really a series about him, it’s about seeing the world the way he saw it, and how I see it after him. What I see makes me suffer a lot, the same problems we had in 1900 are still here today. What I’m bringing is a camera verité. I’m not trying to construct anything.

For Untitled, 1925 Part three (9:57 minutes 2016) it was timely for us to be in Cusco when the biggest ever strike was held to protest about everything! Mining, education, health, all sectors were there. The roads were blocked by the unions, so no one could leave or get in. I felt I was back in the time of 1925 when social consciousness was been raised to a high level.

The indigenous movement in Cusco was happening when my grandfather was there. I don’t know if he was involved, but years later when he came back to Peru, escaping from Europe’s pre-war days, he became involved with the Masons who did a lot of community work in Lima.

With this movie I’m opening questions and questioning myself. What is my relation to these events? I’m white in a country that is primarily indigenous or mixed, so the relationship is not easy. You’re always singled out as a white person, a gringa. Gringa. But I feel the ambience and social problems deep in my skin. It’s very difficult to cope with.

The tourists want the ambience to be crystal clear so they can see the glory of Machu Picchu. But the mist for me contains the aura of the Andes. Once the mist rises you can see flora and fauna. I’m trying to look past what a tourist sees in Peru. I’m trying to say there is life here, drops of water on these flowers, and then I’m going down to witness what is inside the city. I see people who live a natural life, fighting internally, living their own culture — how they grow potatoes, how they build their houses, how they live their lives in the markets.

Cusco was the center of the Inca empire. If you look at the history of Peru, the Inca Empire occupied a huge territory from Colombia to Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru, even a bit of Chile and Argentina. In the early 1900’s professionals and intellectuals in Cusco started to give a central place to the indigenous people, but there was always politics working against them. Since 1900 people have talked about change, while so little has changed. We sat with people on our journey and were invited to take potato soup with them on the roadside. They told us stories so we could hear how the politics are. Why aren’t they allowed to prosper? It is very sad.

We stopped at a hanging bridge that was made by hand. We were so afraid to cross or even to step on it. Then we filmed at a small town bullring where every seat is numbered, painted by hand. I thought of the Spaniard’s bullfighting ring but, foremost, of José Maria Argedas’s novel The Yahuar Fiesta.

The third film reflects on the malaise in the politics of South America, it’s a film of despair. I think about the lack of education opportunities. Some still don’t know basic math or how to read. You see them carrying flags and fighting for a cause in a system that hardly gives them a chance. I saw that during my youth. I grew up in a military state where you can’t do anything, you can’t comment or you disappear or wind up in jail or don’t get your piece of bread. Every day we wake up to another beaten generation. Every year there is another South America country dying of something. It’s like a contagion. A political virus.

Movies

Peace in Columbia (2:43 minutes, 1997, super-8-> U-matic)

Shot in the countryside surrounding Bogota, Columbia. Madi works behind the scenes of a TV commercial (that she produced) for a campaign to vote for peace in the upcoming elections. The smiling actor boys grin through the prosthetic make-ups, then lie down dead on the ground. Teen soldiers grimace as smoke bombs simulate fire fights. The director counsels his young charge – more intensity, more pain! Buildings blow up, a grenade rolls towards a sleeping comrade in slow motion, a family flees their house. Lighting and make-up enter to recreate the illusion, actors mug, and the director takes a final bite. Kinetic, compulsively watchable, driven by urgency.

Correspondence (4:19 minutes, 1999, super 8-> DV)

“We all choose sides eventually,” the film repeats, before its first movement, a blur of racing sailboats. The second brings us a pair of intercut dances, dark-suited Jews and beach revellers, all male. The third movement is also a dance, in the snow, pixelated. The fourth stays close to a brown cola child on the beach. The fifth follows an old cyclist across a dusty, rocky landscape. Finally, an old man walks with a cane, slower than slow. The day is almost over, life is coming to an end, and with it, the film. Found sound by Piller.

Traffidelic (1:12 minutes, 2000, silent, super-8-> U-matic)

Shot from the CN Tower, the handheld camera looks south to the traffic clogs and flows on the Gardiner Expressway. This notebook of a film closes with a suite of ascents and descents from the country’s tallest elevator before settling underneath a single downtown tower. Some of these images were recycled for use in 70 meters (2012).

Process (1:53 minutes, 2001, 16mm)

The artist’s first hand-processed footage arrived extremely overexposed. Made in a Toronto School of Art workshop with Simone Jones. With typical invention and ingenuity, Madi begins to write across the blank screen of her pictureless pictures: “Fuck. Process. Shock. Fear. And Belief.”

Loops (installation, 2002, triple projection, 16mm loops)

Loop #1: Watery shadows offer a lattice of lines and wavy rectangles, coloured by hand.

Loop #2: A composition of colour using optical printing and coloured filters laid directly onto the surface of the film. Everywhere the evidence of the hand, the splicing tape, and the labour of bringing together materials.

Loop #3: A swirl of cascading textures, coloured paint on film, re-animated and slowed via optical printing.

Legend (5 minutes, 2002, super 8 and DV-> 16mm)

This animated brief is driven by a native legend (and allegory) that recounts how wolves were turned into dogs. Music by Eduardo Gonzalez.

My Best Friend’s Son (1:52 minutes, 2003, super-8-> U-matic)

Opening with a suite of intertitle transcripts from Alanis Morissette’s monster 1995 hit You Learn, the song rolls over black and white pics of a young boy and his father palling around an amusement park. The adult world appears in miniature cars, boats, trains, or else in delighted distortions in a bevy of curved mirrors, the camera flowing with its subject, forever in motion. Filmed on super 8 in Columbia, then processed and transferred to ¾” U-matic at Toronto’s Exclusive Film Lab, edited in Bogota, this casual vignette won an honourable mention from the National Film Board on International Home Movie Day.

Graffiti (1:50 minutes, 2003, super8-> 16mm)

Building reflections in water. Originally shot on super 8, then optically printed onto 16mm stock, then hand-painted with red ink and reprinted. The architecture is flowing, breathing. It was hand painted twice, the first version had too much colour for the artist, so she spent several more weeks repainting the works frame by frame.

Chambre de Torture, 1944 (2:29 minutes, 2003, super 8, mini DV, 16mm -> mini DV)

Based on the filmmaker’s father, this movie allegorically replays his experience in wartime France. Opening with a playful animated abstraction, three dots converse as if they were children playing in the yard. These dots dissolve into a nightmare forest, filled with animated gunshots and looming spectres. As a Jewish teenager, Madi’s father went into hiding in Strasbourg. When the war ended, he entered the building that he had watched German soldiers entering and exiting from his hideaway. It was the local headquarters. He found a room there with hooks in the ceiling, and layers of blood covering the walls. Years later, in the 1980s, his father announced that he was going to start painting again, and he drew exactly this scene, a memory haunting that appears in the movie. Sound mixed by Eduardo Gonzalez.

Goodwill (1:10 minutes, 2004, 16mm -> mini DV)

First Nation drums and voices give a living beat to this animated short. Stones gather and circle, a stick bears the word “goodwill.”

Anonymous 1855-2005 (1:28 minutes, 2005, mini DV)

Photographs of nineteenth century couples involved in mutual masturbation and spanking are subject to minimal animated reveries. The whole frame quivers with old pleasures while isolated body fragments are set into motion. Each vignette opens and closes with an iris, each inviting its viewers to engage in one of the oldest sexual pleasures: the act of looking.

Etudes #2 (1:40 minutes, 2006, silent, 35mm)

Shapes flutter and disappear, and then reappear in a dance of theme and variations. The scratched and hand-painted emulsion offer a horizon of expanding and contracting lines.

L’Étranger/The Stranger (2:50 minutes, 2006, super 8-> 35mm)

Begun with super 8 shot by Madi for a peace campaign in Columbia. The footage shows actors portraying guerillas blowing up police stations and killing their own people. Either I will shoot them or they will shoot me. The moment of panic between these two impossible choices is replayed by taking the image through different generations of media, each frame was laser printed, hand painted, and finally optically printed onto 35mm. Sound by Eduardo Gonzalez.

Vive Le Film (2:13 minutes, 2006, 35mm)

A joyous animated celebration of the machines of film-on-film, this large gauge short was made as part of LIFT’s 25th anniversary program Film is Dead! Long Live Film! It turns around a photograph of the artist’s Romanian grandparents, taken at a more secure moment, their 1927 engagement party. Two decades later, following the Second World War, her grandparents would be the only ones left alive. Sound by Madi Piller and Eduardo Gonzalez.

Toro Bravo (3:40 minutes, 2007, DV-> 35mm)

A circus of bloodshed. This movie was made on a digital still camera (Canon D20), and then blown up to 35mm, all edited in camera. Here the filmmaker replays bullfights she recalls as a child in Peru, some shot by her father in the 1970s and then rotoscoped. Dark mining sand was used to lend emotional heft, along with charcoal drawings, cut-outs and photocopies. The red blood was made by using plastercine on paper.

The Old Debate of Don Quixote vs. Sancho Panza (2:20 minutes, 2007, DV and super 8-> DV)

Mixing live-action hand-processed footage with animated interludes (drawings in charcoal, cut-outs, photocopies and photographs). The voice-over is based on a poem by Priscila Uppal which offers the difference between men and women (women read and write books (too smart for their own good – unhappy), men fix cars). Made in collaboration with Priscila Uppal (voice and poetry). Sound by Eduardo Gonzalez. Produced for LIFT Poetry Projections 2007.

Sous L’œil du temps/Beneath the Eye of Time (3:16 minutes, 2010, DV)

Hand-drawn loops via paint-on-glass animation show a pair of dogs forever fighting, or else a mythical bull shimmering in its golden glory, attracting malevolent gazes, or being knocked over. At times the pictures veer into abstraction, dreams without an interpreter. The flames are also a flower. Each action begets the next, as the interdependent chain of living and dying continue. When humans appear the bloodletting begins, they bring a rain of skulls, a triumph of the skeleton. Based on the story “One Little Goat” from the Haggadah. Music by Bob Wiseman.

John Straiton (45 minutes, 2010, DigiBeta, super 8 and 16mm-> DV)

Madi’s longest movie is a portrait of veteran Canadian animator John Straiton. Between 1964 to 1987 Straiton made ten 16mm movies using plasticine, rotoscoping, cut outs and cel animation. A hyper-charged, collage-filled labour of love, this homage proceeds via episodes looking at Straiton’s day job in advertising and his growing interest in cinematography (“I only learned by doing it.”). Funny, irreverent and filled with good-time, home movie tech jokes, the movie works hard to catch the spirit of domestic adventure and self-made media. “I only made that film to show my friends… What I called them at the time was animated poems.” Sound by Eduardo Gonzalez.

My Buddha (installation, 2011, superimposed slide projection with 16mm loop with Richard Gorman painting)

Installation remembering Richard Gorman at the Christopher Cutts Gallery.

Left to Paradise (4:24 minutes, 2011, super 8 and DV-> DV)

The telephone wires tremble and the piano is drunk. We are on a trip it seems, arriving at a suite of photographs that return us to the artist’s former home in Peru. A stand of broken stones, a brace of children, a solo boy looking back from a suitably faded wall. Each picture is punctuated by an animated version of itself, as if the pictures were a heady drop of wine swilled in the mouth, savoured in all its variations. “Come live your dreams” the soundtrack croons, though it often slows to a crawl, as if the effort of conjuring dreams was already too much. Finally this love story of past and present looks at a couple embracing with increasing desperation on the street.

7200 Frames Under The Sun (3:20 minutes, 2011, silent, dual projection, super 8 at 18 fps) // (3:20 minutes, 2011, super 8-DV with sound)

The film is comprised of two super 8 films, each 50ft, created in camera. One film animates the landscape with methodical incremental movements that flash rapidly changing images, offering the flora of northern Ontario. The second film focuses a lingering lens on outcroppings of solid rock exposing fossil-like imagery and sensual shapes that visually insinuate their primal connection to the advance and retreat of the glaciers that were central to their formation. An intriguing soundtrack of experimental music, composed by John Halfpenny, pulsates throughout with a reverberating fusion of dense electronic tones, including some that bring to mind the sound of whales, which might be interpreted as a reminder that the shield was once completely submerged under ancient waters.

Commissioned by LIFT for their 30th anniversary. The sound was added when transferred to video for their screening. The digital version has been adapted for installation and presented as solo exhibition at WARC gallery which included John Halfpenny’s soundtrack.

70 meters (17 minutes, 2012, silent, super 8 at 18 fps)

Lonely cityscapes collide in a memory idyll shot in a scarred and silvery black and white. The country appears in a slow moving colour, a restful idyll, there is at last time to look, and to feel the landscape looking back.

Animated Self-Portraits/Autoportraits Animés (8:49 minutes, 2012, 35mm)

Can a movie also be a community? This labour of love brings together no less than 84 Canadian animators of all stripes – from Michael Snow to the maestros at the National Film Board. Each was asked to provide twelve drawings of themselves which the artist animated on a special 35mm rig. A joyous compendium of outsiders, of barely contained rage and good humour. Music by John Halfpenny. Mix by Eric Culp and Alan deGraaf. Sound design by Joseph Doane.

My Elliot (3:18 minutes, 2013, super 8 with digital soundtrack)

Elliot canes his way slowly into the frame in his blue bathrobe, singing Oh what a beautiful morning on the soundtrack’s voice-over. And sits on a bright blue chair, where his breakfast is waiting for him. Eliot Yarmon is 94, still laughing, taking it one spoonful at a time. A sudden acceleration of camera time speeds his day along into darkness, and then he is back in the chair eating his breakfast again, while he sings happy birthday on his answering machine. Soundtrack by Elliot Yarmon.

Suddenly All Changed (5:49, 2013, silent, 16mm)

Each year more than a dozen artists make a pilgrimage to Phil Hoffman’s week-long film farm retreat, where community spirit and black and white high contrast film dance together. This movie bears the obvious marks of bucket processing, offering glimpses of film drying on a clothesline, as if film and the inspirations that only film might inspire, were the real harvest here. A suite of microscopic views follow, the camera hovering nervously, before the filmmaker appears in the river, immersed, part of the landscape, the observed.

Film on Film (3:18 minutes, 2014, super 8 with digital sound)

Kaleidoscopic structures mirror and dissolve in a circular iris, shimmering with colour, perfectly abstract, shot on super 8 film. The pictures were prepared by painting 35mm film frame by frame. These frames were optically printed and the resulting footage was hand-processed and manipulated. These images were then transposed to acetate cels before being re-animated onto super 8 using reflections in glass. Original music by Rick Hyslop.

Bacchanal (15 minutes, 2014, silent, super 8)

The filmmaker announces: “It’s about music and asses.” Madi turns her poetic lens towards Caribana, North America’s largest street festival, an annual celebration of Caribbean culture held each August in Toronto begun in 1967. In this edition a light kissed suite of glittering objects wink in the sun, before the first face appears, framed in a golden headdress. Dancers gather, the camera staying close in a dance all its own. As the day progresses and the bodies shine with the endless exertion of display, the dirty dancing begins, serial public frottage with audience members temporarily lifts the city’s chronic restraint. Twerk rules.

Dimensions: The Fungi Affair (installation, 2015, Oculus Rift, sculpture and single channel video)

This made-for-a-gallery installation, features Madi’s first foray into the dizzying world of virtual reality. Begun with a series of mushroom photograms onto 35mm film, the VR converts these tactile impressions into an immersive walkabout environment, where movements are controlled by the viewer.

Passage (40 seconds, 2015, DV)

Made during a residency in Dawson City in the Yukon, this hand-drawn animated movie shows a landscape that is broken up into lines and human-made geometries that finally turn into homes. (The movie asks: what is the cost of home?) Horses (or are they dogs?) are tied to a sled so they can transport their human masters. What was once wild is now under control again, restrained and newly useful.

Loops (performance/installation, 2015, triple projection, 16mm loops)

A trio of loops cut for a show in the Setzkasten Gallery in Vienna. Painted found footage. Live sound by the Strangers, and Butoh dance by Adrien Gaumé.

Sunday Solitude (4 minutes, 2016, super 8 and 16mm-> DV)

Shots of an artist’s studio moments in Vienna in grainy black and white gives way to a rush of agitated trees, and then nightlights turning, amusement park incidentals, daytime park casuals, before a graveyard visit in negative turns the mood sober. All of this fleeting, vanishing, disappearing, hardly remembered. Electronic music courtesy of B. Fleischmann.

Into the Light: The Film Resistance (3:42 minutes, 2016, 35mm-> DV)

Mushroom spores contacted onto 35mm for a decade are collected, then printed onto high contrast black and white film, before hand colouring. A cosmological impression, a dazzle of specks and ribbed circles. Made during a residency at MQ21 in Vienna. Music by Stephen Voglsinger, recorded live at Sternstudio Gallery, Vienna during a film performance in April 2016.

Before and Beyond the Image (performance/installation, 2016, 16mm loop, slides, sculpture, and sound reader)

An animated self-portrait in black and white, the artist lifts her arms and as soon as she touches her head, the drawings dissolve into photographic representation. Live sound produced from a sound reader. All the elements are left as an installation once the performance is over.

Untitled, 1925 Part One (7 minutes, 2016, 16mm-> DV)

Each of the trilogy’s three parts begins with a Spanish voice-over, translated into English in a series of short subtitles. They are ghost poetry, speaking for and about the artist’s grandfather, who dared the crossing from his native Romania to Peru in 1923 at the age of 22. Part one is a coastal idyll, the houses are deserted and emit an old light, the waves are rolling, the men, barely glimpsed in the glare, have let their lines out for fishing. Boats and birds turn into temporary shadows. The camera is often on a tripod, steadily looking with an exacting frame, part of the wind, the ruins, the pelicans gathering. Each part of the trilogy is scored with a spare and sober track by Rick Hyslop that provides a delicate counterpoint, here a solo percussion.

Untitled, 1925 Part Two (8:45 minutes, 2016, 16mm-> DV)

Part two in the trilogy continues the search for roots in the artist’s homeland of Peru in a stunning and lyric work imbued with a rare intensity. Beautifully photographed, a masterpiece of stone, steeples, coastline, houses on narrow streets. Footage of the Andes appears in solarized glimpses, the silver mining of this geography echoed in a formal treatment that brings the film’s silver up to the surface. Here is a temporary summit and culmination, a summary work, dense with a lifetime of seeing and materialistic practice.

Untitled, 1925 Part Three (11 minutes, 2016, 16mm-> DV)

The titles present a subject haunted by her own whiteness, destined never to fit in. A stony path opens the way, and then a suite of mist-enshrouded shots cover the ruins of old empires and the Andes. The vegetation is wet and newly alive. After the descent, we enter the city of Cuzco, home of Indigeneous insurgencies for more than a century. The people fill the streets with marches, the markets open, children play football in a courtyard. Bricks are made by hand, potatoes are gathered one at a time, the old ways are the new ways. In the closing sequence, the numbered seats of a coliseum evidence an old colonial order, where everyone knows their place.