Originally presented in the conference “Theory For Practice,” Film and TV School of Academy of Performing Arts, Prague, Dec. 6, 2016.

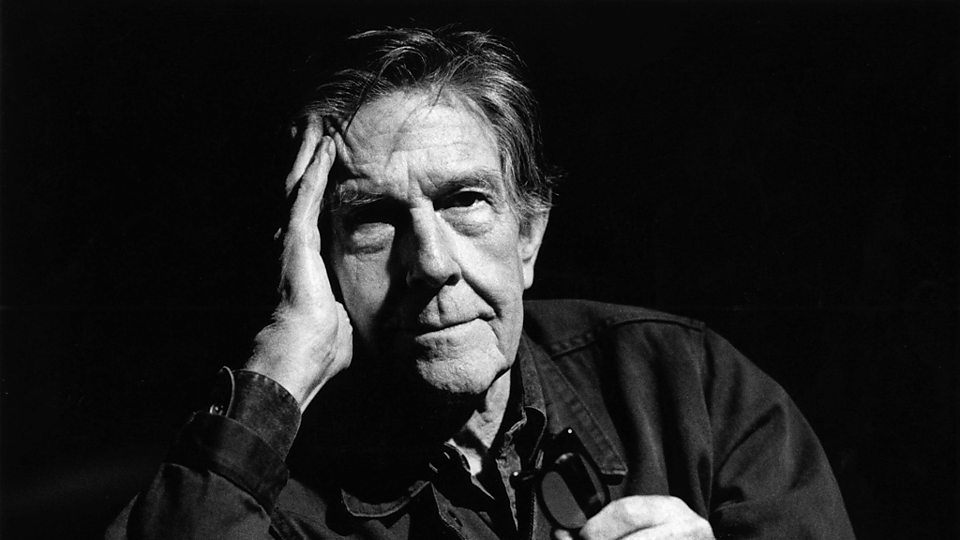

Well I’ve been going back to my old John Cage records, where he talks about university, and he says that university is a place where 200 people read the same book. He calls this “an obvious mistake. Why not have two hundred people read two hundred different books?” You know John was a composer who was trying to get out his cage of a name. The way he would present his work was in concert halls, which are like cinemas, they are public spaces where people gather. I think he’s saying something about what happens when people come together. His hope is that when we arrive at the concert hall the ambition is not to have the same experience as our neighbour, it’s not about reading the same book, instead, it’s about writing the kind of book where 200 readers have 200 different kinds of ideas about it.

Imagine if the hope in art, if the hope in education even, is not to produce agreement. It’s not to produce an experience or an object that we can all agree on, that we find agreeable. What if the hope, the aim, the fantasy, was that we don’t agree?

Learning

Today we’ve come together in a university, and very often gatherings like this share a collective fantasy, a dream, although sometimes that dream stays a secret that can take the rest of your life to unlock. I wondered if our collective fantasy was animated by this question: what if making movies were related to making education? What if the act of learning, and the act of inventing the cinema, were parts of the same duet, the same dance? And I think there is some idea that the talking cure will help us, isn’t there? That the translation of pictures into words has something to do with this relationship between the site of education, the site of learning, and the site of making movies.

I used to think that learning was related to accumulation, learning was going to fill some lack, some hole. I should read another book, watch another movie or make another movie. But some of the most important things I’ve learned have not come from more-and-more-land, which is what our capitalist ecosystem forever encourages, but instead when I can give something up, some cherished belief, some treasured understanding. Education is about knowing less. And knowing less means that I’m prepared to take a bigger risk. For me education is about fear, and our relationship to fear. I believe that making movies, or the relationship between making movies and making education, is about fear.

How to feel open, how to produce the conditions that someone, a student of cinema for instance, could feel safe enough to open, open enough even to risk failure. To take the risk of interpretation. As Maurice Blanchot tells us: when we meet a text, when we meet a book or a movie, in order to read, in order to produce a reading, which is my reading, which is my strange and particular way of moving through the text – making certain parts of the text visible, others invisible – in order to make a reading I have to take a risk. Blanchot goes further, he says: you have to make a leap, a leap of interpretation. And if you do not leap, there is no reading and no book. He says that texts have two sides, the author makes a leap, and the reader makes a leap. There are two sides that come together. And if there is no leap, there is no text. It means that the audience of a movie creates the movie, we become co-directors, or else not, or else the project is a background hum, a temporary distraction.

In order to make a text I have to touch the place where fear lives in my body.

In order to make a movie, to arrive at the place where education is possible,

I need to touch the place where fear lives in my body.

Before we go any further a small confession. I’m not actually saying any of these words, they’re actually being spoken by someone who is sitting in your room in Prague. They might be sitting right beside you. They might be a man or a woman. They might be a man and a woman. They have mastered the art of throwing their voice, of throwing their voice into someone else’s face, into my face. It looks like I am speaking but I’m actually just a representation, an image, I am representing someone, someone who might look just like you.

In the cinema, we throw our voice, don’t we? We take our voice, our ideas, our fantasies, and we throw them into someone else’s body. Or a building, or a tree. The cinema is an art of projection, we project our voice, we allow someone to speak our truth, to speak for us, just like in a democracy, we elect someone to speak, they stand in our place. The image is something that stands in our place. An image is something that we vote for.

Voting

What I can’t help noticing, for instance, here in Toronto, the city of the endless film festivals, is that when I go to the Reel Asian Festival, I see Asian directors making movies with Asians in them. When I go to the Palestinian Film Festival, I see Palestinian directors making movies with Palestinians in them. In other words, I see Palestinians voting for other Palestinians. I’m electing you to stand in my place. And of course, when I watch movies by white people, usually they are voting for other white people. But as we know, white is an invisible colour. In a world of white supremacy, where white men are forever asked to speak at the front of the room, rooms like this, where the president of the country, the university, the company, is always a white man, has always been a white man, whiteness covers everything, it’s voted for so often that you can’t even see it anymore.

First Question

So I guess the first question we need to ask is: what is the first question? How do we start? The starting of a movie, the first step, is the most important step. What if you’re Carl Dreyer and you decide: I want to make a film mostly set in a courtroom, except, sound in cinema hasn’t been invented yet, so there won’t be any talking, in a movie that takes place in a courtroom. Now that is an impossible task, right? Sometimes the first step means you have to find your impossible task. And you have to know this first of all, that it’s not impossible for anyone else, only for you. The movie is a customized vehicle for the impossible, and it’s been designed for one passenger, and that passenger is you.

Portrait

Recently I was approached by a couple of young people who wanted to make a movie about me. We talked about many things when we met, about what it might mean to invent pictures for instance, instead of copying what has already been done. Mostly when people make cinema, they do it according to recipes. Recipes and recipe books are very popular. But is it possible to take a risk, as Blanchot says, to touch our fear, to vote for something that isn’t a recipe? How could you make an individual portrait of an individual, by using a recipe? Though of course it’s the most usual thing,

And all the time I was wondering: what will their first step be like? What are they going to vote for? They asked if we could an interview, and I asked if instead we could have a conversation, perhaps about a theme they suggested of invisibility. Great, wonderful, particularly because one of them is Palestinian. Who would know more about the invisible world than a Palestinian? But when they arrive we don’t have a conversation, instead, they ask me respectful questions, and I provide respectful answers. They are doing the most usual, boring, cliché thing they could possibly do: they are following a recipe. One of the important things they gain from this is that they step out of their own frame. Oh no, this is all about you, it’s not about us at all. I tried to explain that seeing is only possible when both sides are visible. This is what my scientist pals tell me, that molecules change depending on who is witnessing them. We are part of the scene we are seeing, not separate from it. Separation is a fantasy. And by failing to step up and become part of the frame, by staying invisible, they make me invisible too. So the portrait is doomed to fail.

Now the interview, audio only, is their first step. It’s what they vote for. So tell me, what will be the second step? Well, after the words, come the pictures. The pictures follow the words, right? What is important are the words, and then the pictures will arrive as illustration or counterpoint, or in that ugly term they use in North American newsrooms, “B roll.” The images offer only fleeting impressions, they are insubstantial in themselves, what is important is what can be said. That’s the content. This struggle between sound and picture replays the hierarchy of boss and worker (the sound is the boss, the pictures are workers), is it too much to say that the pictures are slaves to the sound? Of course these habit patterns can be resisted, pictures can be used in a different or unexpected way. But no matter how you manage the turn the first step is the most important step, in this case the interview. The first cut is the deepest.

Red Cross

Recently I’ve been invited to work with the archives of the Red Cross. You know they’ve been busy helping people all over the world, feeding kids, setting up camps for refugees, providing medical facilities.

I had to ask this question right away: how can these faraway pictures feel close? How can I let them touch me, I mean, touch the events in my life? The first step was to watch these movies again and again, and then to share them with a group of movie comrades. There was a seminar in Geneva, and all of the students, and I was also a student when I was with them, they turned me into a student, as if I had never seen a movie before, this was so helpful, and we could all work together. This was the first step: an archive held in common, the archive was something that created “us”, a group, and the way that we created a group was not by everyone doing the same thing, or having the same opinion, we create a group out of our singularities, out of our individual expressions. The group is only possible if each of us is able to represent ourselves, in a unique way.

Working with each other we trace the way that seeing and power come together. Who is visible, and who is invisible? Who is professional and wise and powerful, and who is helpless and weak?

This was the first step: to work with, to work with each other, to work with the pictures. When we watched these pictures, which were now our pictures, we liked to ask questions like: The camera person, the person who shot these pictures, tell me, do they live in this faraway place, or do they live here in Geneva? And if the camera person is a white person, in a country of black or brown people, what difference does that make? Do the white people in these pictures shot by a white man appear as individuals, while the brown people look like masses, parts of groups? And if so, how can we resist, how can our group resist the habit patterns that lay inside these pictures?

Yemen

So here they are, the Red Cross movies in the middle of the desert to set up a photo shoot. Check out the man in the middle with the camera, he takes the shot then backs away. Meanwhile everyone is lined up, orderly, posed. The soldiers are striking a pose. It’s easy, everyone just has to play themselves. The white shooters gather on the hill gesturing back, back. You’re too close. And then the close-ups begin, somehow the most obscene kind of taking, taking pictures. Oh and aren’t you young and pretty – we’ll come back to you – but first the warriors and then the exotic, the orientalist fashion. Oh yes the beautiful boy who looks like a woman will carry our flag – and behind him the fighters pose. After a brief motion picture interlude we’re back to stills. Look where this man’s hand is. He touches her breast while the village looks on helplessly. The gestures of knowing, mastery and control.

Disappearances

I wanted to start working with Red Cross pictures from Geneva, from the city we were in. It’s important that our pictures have roots, roots in our experience, in the places we actually live. So I began with a Red Cross movie shot during the second world war. It’s about writing letters, and how the Red Cross is receiving letters from China or America or the Sudan, and getting these letters to prisoners of war around the world. The movie shows a staggering effort, the mobilization of thousands of women and men. And it stages scenes in prison of war camps, showing prisoners receiving letters, and how much it means for them. What is clear is the amount of work, so much work, that went into making this possible, and this is mirrored in the work that went into making this movie, so beautifully shot. Carefully shot. The lighting exquisite.

As I watched it I realized that most of these people are dead now, that many, perhaps even most of these letters would never arrive, that the Swiss dream of order and contact and connection, was beautiful partly because of its failure, and so I copied every shot of the film, and made them shorter, and then added a fade, as if each moment was leaving, as if each face was disappearing, as if the whole world was ending over and over again. Which of course it was. Which of course it still is.

The fade allows us to see both sides of the picture. The terrific effort that is being made, and the failure of those efforts. I am voting for both sides with these fades.

Beirut Grammar

OK, now we’re in Beirut. The Palestinians who were forced out of their homes in 1948 in what used to be called Palestine, but what was now newly called Israel – at the moment the new state arrives, it expels the local population. It’s an old story, perhaps the oldest story, and 100,000 Palestinians wind up in Lebanon, in terrible conditions, and in the mid-70s, decades later, they start fighting against the Christian government. The large Muslim population takes sides and switches sides, and many other countries get involved, including Israel which invades Lebanon and kills many people.

In the midst of this war, the Red Cross come and set up hospitals, and try to reunite families. Their cameras aren’t focused on an individual, as usual they shoot a little of this and a little of that. This broken building, this passing group of construction workers who are also fighters, this little girl with her mom pouring water into a pail because there’s no plumbing and no houses.

How could we show these pictures so they can be seen? The question is about visibility. The commonplace is that if a picture is in a movie, or even if an entire movie is being shown, then it is visible. But of course, that’s not true at all. There are many ways to create invisibility. The old way of creating invisibility was by stopping pictures being shown. The new way is by showing too many pictures. If you go to a festival and watch several features a day, you are making some of them invisible. My pal Yann Beauvais used to run a weekly program of difficult movies in Paris for years. He said that in every program of short movies there was one movie that was a spacer, a throwaway, a palette cleanser, it simply cleared space for the next set of movies. In other words there was one movie that was basically invisible in every program. If you program two movies that are very similar, or if you put together a program of shorts that all have a common theme, you bring to the surface a certain quality, and you repress or throw away other qualities, and by eroding the lines between movies, you begin to produce new forms of invisibility.

One of the ways that the Red Cross movies create invisibility is that they show somebody, who doesn’t talk, in a group setting with a bunch of other people, and we see them only once for a few seconds. How can we remember this face? How can we know their song, their joys and hopes? What actually remains of, for instance, a panning shot in a street? So my job was to work against this habit pattern, to create visibility for the new city of Beirut, the city of Red Cross pictures, in this mini-archive that exists in a single movie. I’m watching this movie again and again, I’m getting to know these streets, these faces. How can I share with you this experience? I decided to work with a very simple math model. It goes like this: 1+2+3+4+5+6… I would show the first shot, which you can see here is a citizen soldier, running through an empty field in the city, and then a space, a blank, and then we’ll see him again, and add the second shot, a man cleaning his apartment, and then blank, and then we’ll see the citizen soldier, the cleaner, and then a car. The movie will chain together shots, like memories, and slowly present a picture of this city. And slowly we’ll come to know and recognize these pictures, like an old friend, like the way these two brothers touch on a street, the camera, the act of looking, exerts a pressure, and I’m going to respond to this pressure, this fear, by touching my beloved brother.

Greece

Let’s take another example. The earliest moments of the Red Cross movie archive dates back to 1922, during the war between Greece and Turkey. The Red Cross were involved in negotiations that helped bring prisoners home. There is footage, just a little footage, of Turkish prisoners waiting for a boat to take them home. Once again, there is a crowd shot, it’s the most usual thing, and because the shot is very short, and the view is very wide, it’s hard to see anything. Here is another way of creating invisibility.

How can I make this moment visible? By changing the time of the shot. Cinema is an art of attention. It asks: what do we pay attention to, and how do we pay attention to that? Here, I slow the shot down, so I can see the faces of these men, I am voting for their faces, and as soon as you seem them you can’t help noticing that almost no one here is moving, except the white guy with the hat, obviously he’s a red cross boss, he’s organizing things, getting things done. It’s as if everyone is frozen in a time lock, except for him, he’s free to move. And while the whole point of these pictures is to show the men going home, I couldn’t help feeling that some part of them would never leave home, right? Some part of them would never leave this place, the place we are seeing right now. These traumas, these difficulties, live inside our bodies. Our bodies are made out of memory. So the movie becomes about this tension, between the Turkish men who are trying to get home, who will never be able to leave this place, and the emissary, the boatman who will take them across the river of death, the man with the hat, and a red cross in place of a heart.

Vietnam

Let’s track another Red Cross moment. We’re in a hospital where the Red Cross are looking after Vietnamese folks injured in what they called, in Vietnam, the American War. So here is the original footage, this poor kid reduced and shrunken, squatting while the nurse performs her masterly gestures. She’s in charge, a professional, performing her duties, repeating official gestures from the manual. She’s the top, he’s the bottom. Watch how we help the natives, they need us, and slyly, secretly, there is another message: how much cleaner and more scientific and progress-oriented and how very white we are, the ones who made this picture, the ones who are making this medicine. It is a quiet image of white supremacy, or is that too much to say? They are helping out after all.

As I have presented each of these Red Cross movies to you, I’ve tried to lay out how the original pictures, which are already a kind of mini-archive, these pictures lean in a certain direction, they have a point of view, they are interested in making a point, in presenting certain kinds of evidence. Again and again, I am trying to find the other side. So if the original footage is interested in a celebration of mastery and professionalism and control (hey, look what a great job we’re doing here) I would like to show the other side: the unprofessional, not a vertical relationship (boss and worker) but horizontal – a relationship of equals, and what could be more equal than the moment we fall in love? Yes, I’m rewriting these pictures as a love story. And I’m going to give him a voice, because he’s the one who has been left behind here, so I’m going to turn the background into the foreground. In the original footage he is like a stand-in, a piece of furniture even, he’s necessary for the purposes of demonstration, he could be anyone. Look how we’re treating these wounded people. But in my movie he becomes a person, a locus of desire, an attitude, and most importantly, a subject. What defeats the project of white supremacy is to find a subject on the other side that is not white. I absorb these pictures reflecting on my own mother, and her experience in an internment camp, and how she is not white, and how she also wanted to fall in love, though too often was condemned simply to fall because there was so little to eat.

We throw our voice into the voice of this young man. In the hope that you will throw your body into his body, into her body. Oh, I can identify with that, I have also been in love. The cinema is about throwing your voice, in the hopes that someone else, an unmet stranger, an audience perhaps, might throw their bodies into these bodies of light. And at this moment the archival picture, which is old and dusty and from some past world we can hardly imagine, at that moment the past becomes present. We don’t throw our body into the past, we’re doing it now, in this moment. There’s a collapse between past and present, then and now, your body and my body. It’s so satisfying. And it helps me to be human. It helps me to feel your feelings.

Writing

In order to create visibility, to make something else visible, sometimes it’s necessary to scribble over the picture, to make some audiovisual graffiti. The voice, it’s a question of the voice, isn’t it? Doesn’t every liberation movement – whether women’s liberation, black liberation, gay liberation – isn’t having a voice, coming to voice, a necessary, a central piece of this liberation? It’s as if liberation isn’t possible until the voiceless gain a voice, until those without a voice can speak and be heard. Sometimes in order to liberate a picture – is that too large a word to use? – in order to give these pictures a voice, to create a subject, sometimes it’s necessary to introduce language – in voice-over, in superimposed titles, or intertitles, like in the earliest movies.

Palestine

I recently watched Lia Tarachansky’s movie On the Side of the Road. It looks at the moment that the Israeli state began, in 1948, and how armed Israeli soldiers terrorized Palestinians, massacred Palestinians, chased them out of their homes, cleared entire villages. There are soldiers who participated in these war crimes and they testify to these events. These are facts, undeniable facts, and yet, in the state of Israel, most Jews do not believe these things happened. After the movie Lia was asked: how can we change this? Why doesn’t showing facts to people help to change their mind? Lia said: facts don’t matter. You can show someone a photograph, you can bring them an eyewitness survivor, you can show them a video, it doesn’t matter. We all wear blinders, we have certain ideas about the world we live in. If facts don’t fit our views, then we throw them away, we say they are non-facts or non-sense. And if total bullshit arrives, and it fits our worldview, we eat it up right away and say: that tastes good, that is the truth.

Wow, so facts don’t matter. So if facts don’t matter Lia, please tell us: how can people change their opinion? She said: people change because of their heart, and the head follows after. You have to feel what another person feels, you have to temporarily drop your views, because the feeling, the heart, slides through all of your ideas and views, and this feeling, this ability to jump into someone’s body, this jump happens, which is also Blanchot’s jump, the risk of interpretation, the risk of translation, the risk of living in another body, it is the biggest risk we can face as human animals.

sync image fades in: Oh wait, I can feel myself coming back from a dark place, I’m so wispy and immaterial, like a ghost, but slowly I can feel myself coming back to you. I can’t even see through my body anymore. Oh, there we are, we’re back. Did you miss me? Did I miss you? Did we miss each other? Have we been missing each other? In the cinema, or in the place of education, perhaps we can hope for at least this: that we will miss each other, that we will get it wrong, that we will translate a phrase, a sentence, a face, in our own way, according to what we need. The hope is that these words and pictures might help each of you to come to your own conclusions.

Let’s go back for a moment and review. I wanted to say a few words about pictures, how very often a picture is given to us with a certain point of view, it’s like the picture is leaning in a certain direction, and my interest is finding out what is on the other side. If the picture is about power and desire for instance – what picture is not about power and desire? – then I would like to move that place of power somewhere else, or I would like to lift the curtain and show how that power works. This question of two sides, the inhale and exhale, the audience and the movie, the viewer and the viewed.

We spoke about needing to take a jump, a leap of interpretation, and that without that leap an image was not possible, it’s part of what Barthes named the stadium, the endless faceless faces we encounter, the unremembered, it’s just writing on water.

The cinema is a jumping ground, it’s a place where we learn how to jump into each other’s bodies, into experiences that are crazily different than our own, but we can feel them, they become part of our repertoire. Instead of a fate a repertoire. We feel someone else’s fear, their joy, their delights. This can help us feel human. We talked about creating subjects, finding subjects, even if that subject is a wall or a Palestinian, or a warrior in Yemen, or a brother touching his brother’s arm in Beirut, or a girl filling a pail, or a young and injured Vietnamese boy falling in love with his nurse. The invitation is to make a jump, even though it’s a lot to ask, who has the time after all, our computers are time bombs that have stolen all our time. When I worked in Geneva my students, who were barely twenty years old, said that they were running out of time. Wow. Perhaps the cinema of found footage is a place where we can gain time, where we can waste time, where we can learn to forget, because forgetting is such an important part of memory. Let’s come together to be apart, to learn how to be ourselves, but only when we’re with other people. A self in a crowd. In the dark.