This year it’s all about money. Whose got it, who doesn’t, whose in, whose out. It’s that simple, it’s that straight forward. We don’t have to worry any more about taste, or theory, I mean, no one reads theory anymore do they, that’s so 1970s. So pack up your beret, your semions and simulacras and get with the program, because only money will tell us whose hitting the mark and whose yesterday’s hope. Money will separate the artists from the weekend heroes, and I don’t know about you, but I’m getting my bets in early.

This year it’s all about visibility babe, or in the mantra of my real estate agent: location location location. You got to be seen to be a player, and if you’re not busy being visible you’re off the board, you’re history. And history is the only thing in our past which ain’t ever coming back into fashion.

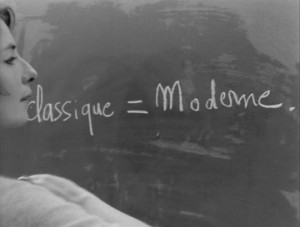

Which brings us to experimental film. Fringe film. The underground. The avant garde. Brought to us, like the Internet, courtesy of the military. If the good folks at the Pentagon and the Wolf’s Lair hadn’t wanted to watch the mayhem close up, there wouldn’t be any cameras light enough for one person to hoist over their shoulders and without that you got less than zero.

Scratching your titles onto the fringe used to be cheap, or at least, not the rent money, but then reversal got phased out because the news room turned from film to video and the prices have never looked back. Who can afford this, except for the already well off, the middle class, the tenured professors and professionals who do a little business on the side, pull out the gold cards and get it done, cut back on the frappacinos so they can lay their money out for some good old fashioned subversive us-versus-them personal-stories-only-please avant-gardism. Show me the money and I’ll show you the Bolex, the three chip digital vid camera. You’ve got the big picture in your hands now and okay it’s too late to even hope to be Stan or Maya or Steina but with a little schmooze, with a little help from your friends, you might be able to muscle into the next MOMA schedule, or strut your stuff into the hundreds, no make that thousands of festivals which pop up on your desktop every morning, eager, ready and willing to pad that résumé.

The fringe is founded on invisible economies not based on money but on something else: the promise of sex, a cause, some vague utopian hope that something, somewhere, will be better if this film, this panel, this conference will be held. Every year, countless hours are spent by the unnamed—the ticket takers and projectionists and floor sweepers of the avant garde, the theatre directors trying to squeeze in a little Abigail Child between the Fellini retros, the web masters still too young to be pulling in the serious coin, adding a little flash to the online fringe. There’s no money in it, so most just stop. They grow up, lead responsible lives, they have mouths to feed. And yet there are always the misfits, the ones that go on, the ones without money. And of course there are the young, they’ve only spent their parents money. If they were really poor they would never hear about the fringe, because the poor never do, it belongs to the middle class, and especially to the young middle-class—perched somewhere between their first job and their first mortgage, they are the fodder for avant events everywhere. The target audience. And surrounding every event, there is advertising, the call for bums on seats, the zero sum game of money.

“Consumerism is no longer about conformity but about difference. Advertising teaches us not in the ways of puritanical self-denial but in orgiastic, self-fulfillment. It counsels not rigid adherence to the tastes of the herd but vigilant and constantly updated individualism. We consume not to fit in, but to prove that we are rock and roll rebels, each one of us as rule breaking and hierarchy defying as our heroes of the 60s, who now pitch cars, shoes and beer. Programming and advertising become interchangeable as consumers live inside a perpetual marketing event. The advertising life is not merely what you see on TV, it’s what the television sees. It is now everything that surrounds you.”

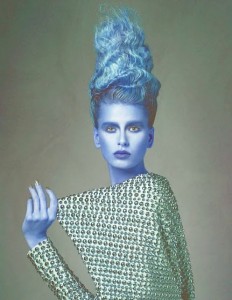

MTV, for instance, has become the new champion of the short film, the accumulation of visual tics which became style in the hands of its underground forbears is now part of a familiar lexicon on display 24/7. Welcome to the avant garde babe. Tune in, turn on, and keep watching. I have seen the future, and it’s a SONY.

“MTV is what the Harvard Business Review calls a ‘marketspace,’ a consensual hallucination where ‘product becomes place becomes promotion.’ In the marketspace the context or contextual surroundings—not the content of the actual programming—is what attracts advertisers, and at last vehicle, style, and the language of the quarterly report have become one. This is how the network’s “radically different future” derives directly from the business imperatives of the most conservative past.”

“Some legendary exponents of the countercultural idea have been more fortunate—William S. Burroughs, for example, who appears in a TV spot for Nike. But so openly does the commercial flaunt the confluence of capital and counterculture that it has brought considerable heat down on the head of the beat king. Writing in the Voice, Leslie Savan marvels at the contradiction between Burroughs’ writings and the faceless corporate entity for which he is now pushing product. ‘Now the realization that nothing threatens the system has freed advertising to exploit even the most marginal elements of society,’ Savan observes. ‘In fact, being hip is no longer quite enough—better the pitchman be ‘underground.”Meanwhile Burroughs’ manager insists, as all future Culture Studies treatments of the ad will no doubt affirm, that Burroughs’ presence actually makes the commercial ‘deeply subversive.’ ‘I hate to repeat the usual mantra, but you know, homosexual drug addict, manslaughter, accidental homicide.’ But Savan wonders whether, in fact, it is Burroughs who has been assimilated by corporate America. “The problem comes,” she writes, ‘in how easily any idea, deed, or image can become part of the corporate world.’

The most startling revelation to emerge from the Burroughs/Nike partnership is not that corporate America has overwhelmed its cultural foes or that Burroughs can somehow remain ‘subversive’ through it all, but the complete lack of dissonance between the two sides. Of course Burroughs is not ‘subversive,’ but neither has he ‘sold out.’ His ravings are no longer appreciably different from the official folklore of American capital. What’s changed is not Burroughs, but business itself. As expertly as Burroughs once bayoneted American proprieties, as stridently as he once proclaimed himself beyond the laws of humans and Gods, he is today a respected ideologue of the Information Age, occupying roughly the same position in the pantheon of corporate-cultural thought once reserved strictly for Notre Dame football coaches and positive-thinking Methodist ministers. His inspirational writings are boardroom faves, his dark nihilistic burpings the happy homilies of the new corporate faith.”

In 1991, NIKE announced that they would hire a Canadian indie filmmaker to direct a pitch, and two avant-gardists hit the short list: Ann Marie Fleming, a first person monologist of considerable élan, and Carl Brown, a home chemistry major whose vast output is largely unknown even in the city where he works everyday delivering mail. Neither thought twice about accepting the charge, which of course eventually went to David Cronenberg. It was considered an honour, a step up, a perverse form of recognition. And of course there was the money. Gariné Torossian, a Toronto-based emulsion bender of the first order, sired in a line of Armenian weavers who has found a way to knit and braid emulsions, was not even so lucky as to be unchosen. When Jann Arden’s video appeared at the beginning of this year, it was clear the director had copped his licks directly from Torossian, all of the signature trademarks were there, but there was never a phone call, an acknowledgment or an apology. And for years the Filmmaker’s Co-op in New York shipped out boxes of the new fringe to ad agencies in Manhattan, ready to strip search the contents for new ways of saying yes.

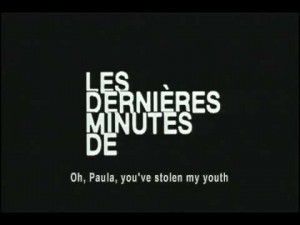

Here lies the conundrum: insofar as attention may be granted, success achieved, they will find you. It’s just a question of time. They will turn you into another part of the flow. It’s when you know you’ve really made it. Arrived. Because as Foucault was fond of saying, There is no outside. On the other hand, you could just be ignored, making your small things on the fringe, far from the madding crowd, removed, withdrawn, refused. Government sponsored resistance, tenured iconoclasts, brave new emulsions. We’ve got an APB for an opposition party but the line’s stone cold. There are rumours of course, and graffiti on the bathroom wall. What if you change just one person. That’s what they tell me. Acting locally and thinking globally. That’s what they tell me. But the screenings have come and gone, the posters shredded, those films already turning into magenta dust, and no one can remember. I can’t even remember coming here today.

When I hear the word avant-garde I reach for my NASDAQ shares. If you wanna win, you gotta play, so spare me the avant whining. It’s dog eat dog star man out there, and those not busy being born are busy eating their heart out. Though as big Bill showed us, it’s never too late to start selling short. Sure I’ve got a few friends who’ve swapped their RRSPS for Tri-X, but do you think they’re any happier for it? So when my kids ask me, “What did you do during the image wars daddy?” I’m going to give it to them straight: there are no small films, only small audiences.

Originally published in: Public 25 ‘Experimentalism’, Fall 2002