Talk History: an interview with Philip Monk (January 15, 2013)

Mike: What struck even casual visitors to the Funnel, Toronto’s former fringe movie theatre, was that when luminaries (local or otherwise) showed their work, followed by the requisite question and answer session, talking was strained and difficult. I’m wondering if that was unusual in Toronto?

Philip: If you go to a talk in Toronto now it’s still the case. I don’t know whether it’s specific to this city but I don’t think it happens everywhere. Presentations here are invariably followed by an awkward silence before somebody starts up a discussion. In general there isn’t a lot of participation by the audience. The audience doesn’t seem to be able to carry the discourse, or is too anxious about their own lack of authority. I think it’s endemic to Toronto, whether it’s endemic to audiences in general I don’t know. There’s always been a lack of discourse in Toronto though there are brief moments of efflorescence when it happens.

Mike: The public talks and publishing you’ve done, is that a way to address this absence?

Philip: I’ve had a different status in the arts community over all these years. I was most active in the community in terms of writing and speaking when I was an independent writer. 1982-84 was the high point of discourse and discussion in Toronto, there were many lectures, talks and symposiums organized within the community. It was a highly theoretical moment in contemporary art, in part because of the breaking of postmodernism around 1979. In Montreal Parachute Magazine organized a lot of talks, and that filtered back here. There was a generational change within the art community, and something different was happening in art criticism because of French theory and the Frankfurt School, Walter Benjamin’s allegory, etc. It was a period in which New York was reasserting itself, October Magazine was newly ascendant, so Toronto was catching up and copying again. I think the community was a bit more self aware and self conscious about creating itself as a community. But it was very short lived, and really ended around 1984-85, and nothing’s picked up again. There have been decades with a paucity of talking about art in Toronto.

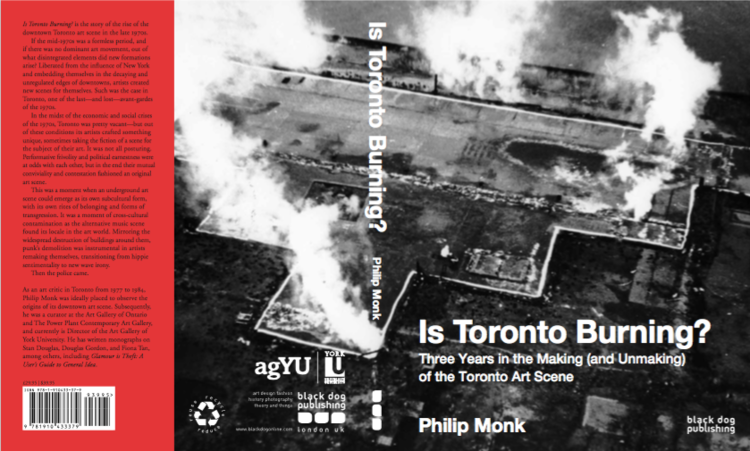

In the early eighties I decided to dedicate myself to writing a history of art in Toronto, trying to deal with the lack of a history. There was a problem of history being in arrears, you can never catch up because you don’t have an older history to fall back upon — to follow or critique. There’s always been a resistance to stating, writing, establishing or proclaiming a history of art in Toronto. People constantly criticize me for my idea of a lack of history, but I don’t know why. Tell me where the histories are. Nothing has been synthesized, where are the books, the articles? There have been few attempts to set something in place from a particular point of view. There is no Toronto discourse we can point to, or histories of Toronto art we can point to, and I think that’s a problem. A separate problem is the resistance to writing this history.

Mike: Why has that resistance been sustained across different generations?

Philip: It goes back to that era in the eighties, and became exacerbated in the late eighties when issues around appropriation of voice became more prominent. The orthodoxy became: you can’t have a history if it’s not all inclusive. You cannot have a point of view or representation that isn’t all inclusive. And that isn’t possible. Because if you write a history you have to make a representation of some sort, you have to select and value, establish lineages, chains, series, where some moments are more important than others. You can’t include everything.

In the late eighties there was an episode that scared people off from trying to write or demonstrate a history through exhibitions. That was the inaugural exhibition of the Power Plant in 1987 called Toronto: A Play of History. There was a panel discussion that was organized by the Power Plant, and all the participants were so critical of the institution, the exhibition, the Roots sponsorship, that curators were afraid to do a Toronto show thereafter. No one did a Toronto show for years until I did exhibitions at the Power Plant in the nineties These shows weren’t all inclusive but thematic Toronto group shows. To my mind that episode kicked off a curatorial fear of trying to represent our own history because they would get dumped on by the whole community. How dare you represent a history that’s not all inclusive? Therefore we have a lack of history and we suffer those consequences.

Mike: CEAC was an organization that was concerned with its documentation, preserving continuities of thought and action through their magazines first of all, the hiring of a librarian (John Faichney), and the establishment of an artist-book library.

Philip: It’s hard to know because they were so short lived. I’m not impressed so far by how well they’ve documented their activities. The fact that CEAC is so unknown points out a certain failure on their part in that regard.

Mike: Did you ever go to CEAC?

Philip: I was a student at that point, I never got involved in CEAC. I went once to try and find out about some of the events that were advertised, and then the whole thing fell apart. My knowledge is archival.

Mike: After the Toronto press declared CEAC a government funded terrorist organization, both arts councils unilaterally withdrew funding. There was little protest by the artist community, does that surprise you?

Philip: I vaguely remember the events happening, by that point I did have Strike Magazine. But I really wasn’t involved with the arts community so I just read what happened. I’ve seen the letters from the faculty at York (Bruce Parsons, etc) that were published in Only Paper Today. I don’t know if there were any other responses to CEAC, other than that letter. From what I read the arts community was very frightened, and they were protesting the lack of access to CEAC’s equipment.

Mike: It’s hard to imagine a similar non-response today.

Philip: There are new rules at the Councils about defunding, you can’t lose all your funding at once. But no artist-run centre could function the way CEAC did. I think there would have to more accountability around money and content. The AGYU (Art Gallery of York University – where I’m a director) functions as an intellectual enterprise, and we have some social responsibility to our community. But we’re not doing that from a strict political position, we’re not Marxist-Leninists, we’re not even anarchists (laughing). I think it would be difficult for an artist-run centre today to operate as its own ideology. CEAC was an ideological entity promoting a position, not responsible to servicing artists. The presenting face of the organization was not an exhibiting space, but the ideological profile of the core group running CEAC. That’s the impression I have, looking at the historical documentation.

I don’t think the councils would fund a group so its members could make work. That’s a collective, not an artist-run centre. In the 90s in Toronto there were various collectives that turned away from the artist-run system. They took charge of their own financing and didn’t look to the government because a collective only serves its own members. It would be hard to find councils willing to fund a collective that wouldn’t serve other artists. CEAC was producing art, but they were producing for themselves, and using CEAC money to promote themselves. The publications and tours were about promoting themselves. This isn’t a judgmental point of view.

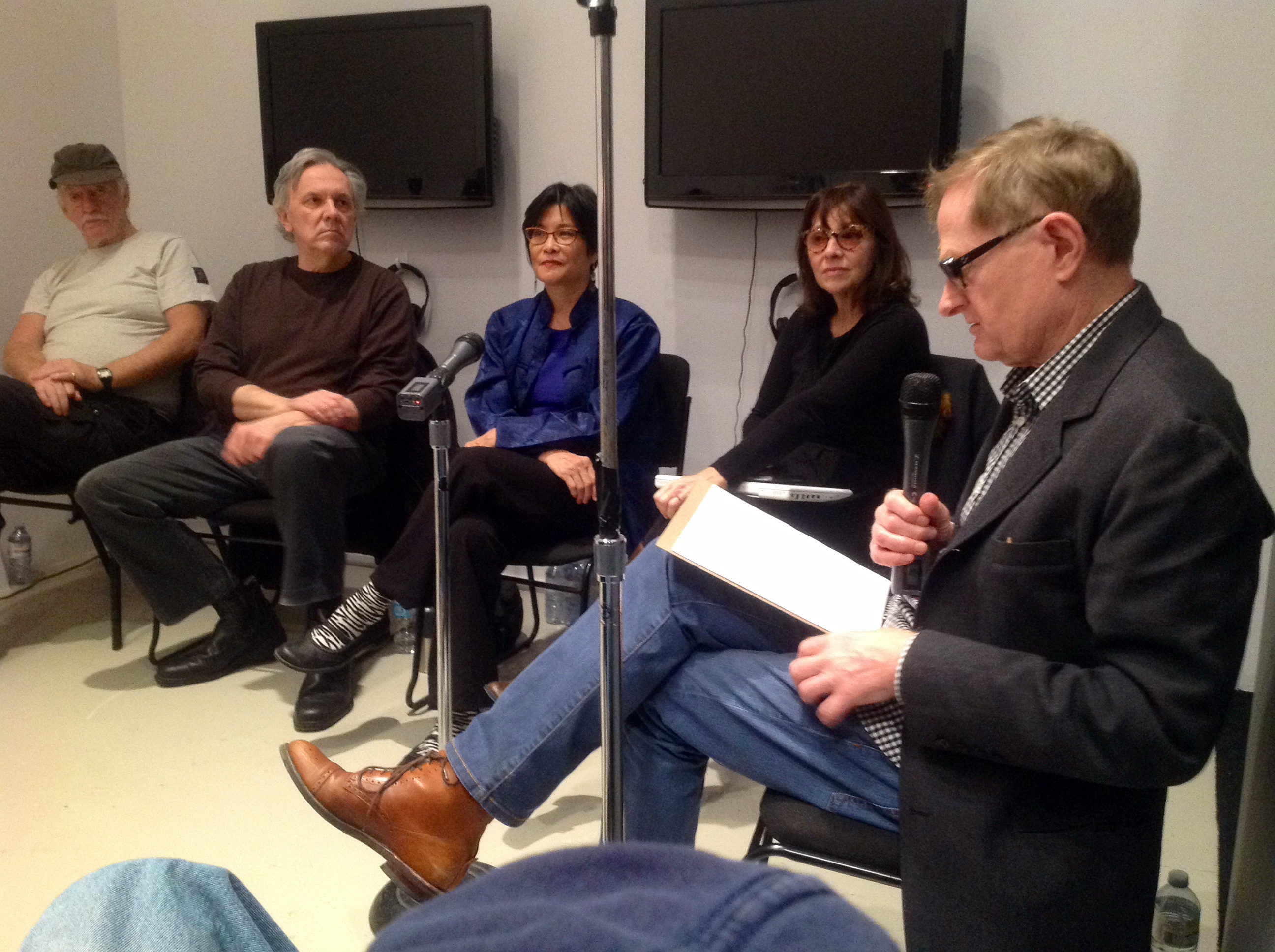

Ron Giii, Peter Dudar, Lily Eng, Diane Boadway, Philip Monk in CEAC panel 1, Art Gallery of York University, Oct 2014

Mike: Is that distinct from what General Idea was doing?

Philip: I think there are similarities between the two groups, I’m writing an article about that right now. Obviously they both had their own magazines, and used those magazines initially to promote something else but eventually to promote themselves. Or themselves and their ideological friends. They were both highly aggressive, and both developed a rhetorical language about themselves through their publications. They both had a notion of what effective art should be. Both were highly ambitious, highly talented, very smart people operating. Both had a certain amount of charisma to be able to draw people towards them and support them. One survived, the other didn’t. Both developed rhetorical models and existed on those models. One rhetorical model survived, the other blew up. General Idea’s rhetorical model was more cushioned by the frameworks of art discourse, while CEAC’s rhetoric was increasingly anti-art. I think there are interesting comparisons between the two, I’m working on an article that looks at the dialogue between General Idea’s File Magazine and CEAC’s Art Communication Edition/Strike. There is a certain rivalry between the two groups, an unspoken critique of General Idea that operated through Art Communication Edition that set CEAC’s direction, though General Idea was never explicitly named.