Intro to Funnel screening at TIFF Cinematheque, Toronto

January 31, 2017

by Mike Hoolboom

I’m going to talk for ten minutes.

I’d like to begin with an announcement, offer four thank yous, give a brief intro to the Funnel, and then to the program. We’ll watch the movies, then a number of artists who are present will come and take questions.

Announcement. On Thursday night – that’s two more sleeps – on Thursday night at 7pm at OCADU in room 230 there will be a panel about the Funnel. I know that going to a panel is like taking vitamins but Thursday will be different. David McIntosh will be there, former Funnel director, Judith Doyle used to be the office manager, and Dot Tuer was on the programming committee and wrote catalogues. They are prodigious speakers, teachers and mentors, gifted in the arts of spontaneous expression, that’s 7pm Thursday.

Thank you first of all to everyone to contributed to the book, like the Funnel it was a collective effort. Some offered drawings, photographs, and many of course their words and memories. Special thanks to Clint Enns who was an early believer and who accompanied me to the archives. The manuscript was a sprawling mess until it reached editor Jason McBride who simply held up the book he’d edited about Will Munro, Army of Lovers, and said: why don’t you make it more like this? I tried, and it really helped. Cam Moneo was the proof reader and fact checker, and finally I’d like to thank the person who put it together, this is book number five that she’s designed for me, including books by Mike Cartmell and about David Rimmer, Emily Vey Duke and Dani Leventhal. Her name is Kilby Smith-McGregor. Thank you very much.

The book is divided into three sections. Before the Funnel, the Funnel, what went wrong. I’d like to offer a quick summary of the first chapter which looks at the swirl of events that led to the creation of this experimental film collective that was vertically integrated, like the old Hollywood studios, not only was it necessary to build their own theatre, to show movies, but also to make movies, distribute them, run an art gallery, offer workshops and catalogues.

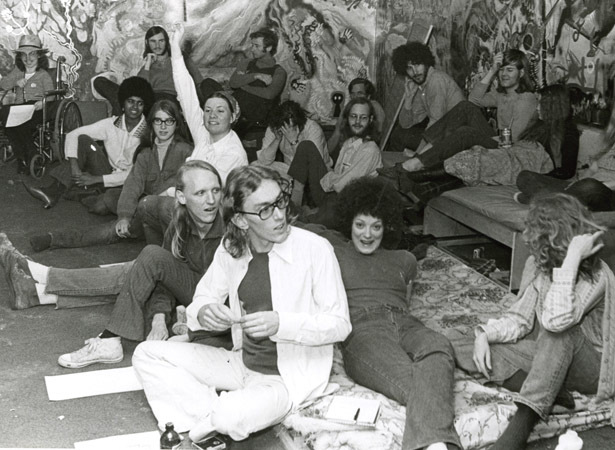

Here is picture number one. There was a dress rehearsal for the Funnel, what could be more Canadian, called Buck Lake, part of the back-to-the-land movement. It was an hour and a half’s drive north of the city, 100 acres of forest, an artist collective, loosely knit. Two future directors of the Funnel, as well as key personnel lived there off and on. They came together to live in a space that was separate from capitalism and mainstream culture, as Keith Lock who went to Gwartzman’s Art Supplies to buy a hunk of canvas that he turned into a teepee and lived in for a year, says: the question was how do you get outside the system? Both the Funnel and Buck Lake were concerned with alternative technologies, and were held together by artmaking, volunteer labour and common ideals.

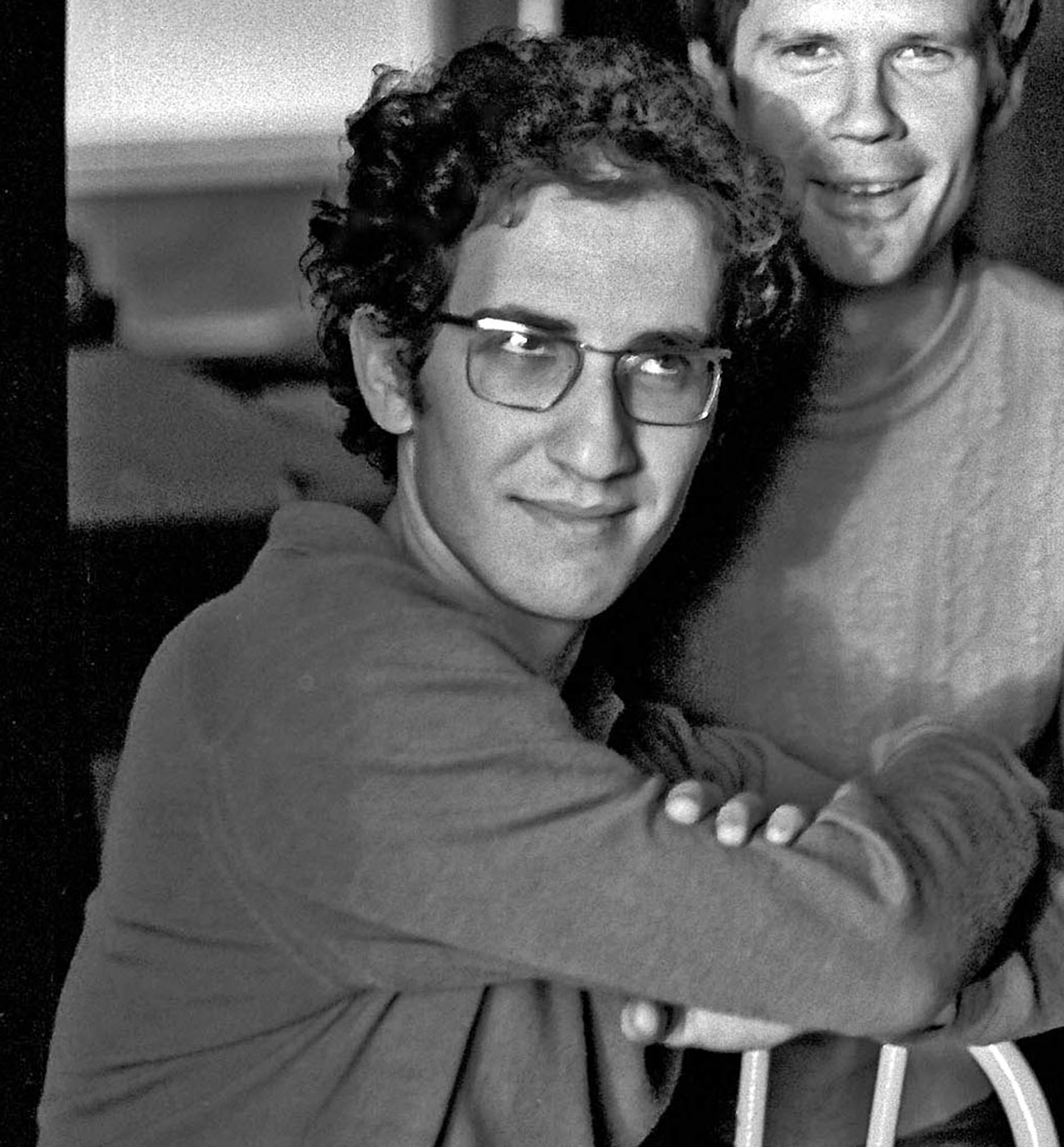

Here is picture two. There were two Toronto festivals in the mid-70s, one of them poached the best flicks from other fests and called itself the Festival of Festivals. The second festival was called… the Toronto Super 8 Film Festival. It was begun at OCA – the Ontario College of Art – by three people. First among equals was Scott Didlake,he was an American draft dodger, and it is impossible to overemphasize the importance that American draft dodgers had on Canadian culture. 100,000 people came through the border, they were young, educated, politically savvy. Scott Didlake did the heavy lifting, he was helped by Shalhavet Goldhar (who would go on to make the wondrous Mold Grows on Baby), and of course Ross McLaren, a witty, ambitious film student who was already making beautiful movies. The first fest was a great success, mostly held at the art college. But after it was over it was taken over by Richard and Sheila Hill, Richard was running the film/video dept at OCA at the time. They bigged up the whole shebang and brought it to Harbourfront. But the three folks who had started the fest were banished, they were out, and they all felt that something had been taken away from them. This sense of betrayal, of establishment values versus the underground, was an early and formative experience in what would become the Funnel.

Here is picture three. The Funnel was not the first film co-op in the city, that honour belonged to the Toronto Filmmakers Co-op. It was housed in Rochdale College, an apartment building that still stands at Bloor and Huron. It was a student-run free university, a housing co-op, a daycare, and it was active culturally, housing alternative theatre and literary groups, including the Filmmaker’s Co-op. If you wanted to get high you could just walk down the hallways and inhale. It’s hard to imagine today when a movie studio can fit into a telephone, but in those days expensive gear meant that collective ownership made the most sense, expensive cameras or editing gear or tape recorders could be shared. It meant that equipment was something that brought people together, unlike today where equipment often disperses people. It also raises the question of space: where are we going to put the gear, and where are people going to come to use it. The Co-op was run by anarchists for a spell, but eventually Bill Boyle was hired, and he and his board decided to professionalize – buy better gear, cater to the small independent mostly documentary production orgs in town. Costs went up, the old idealists and artists were pushed out, and soon things had spiraled out of control.

At the very last moment who should show up but a group of people who had begun running super 8 open screenings, they weren’t yet called the Funnel, but they were looking for an organization. They filled the board, Ross McLaren, Anna Gronau, Tom Urquhart, Adam Swica, hoping to recreate the Co-op as an artist’s film joint, only to find out that the money was gone, the co-op was dying, and they presided over this death. Once again we have an initiative that was started by artists, that was taken over, or at least this was the perception, that it had been taken over by so-called corporate interests, by people that had no common ideals or sweat equity, and then it died.

Here is picture number four, the final picture. Meet Amerigo Marras, an Italian architecture student at the U of T. Who does he meet there but the love of his life, yes an American draft dodger Donald Suber Corley. They move in together and eventually turn their Kensington Market house into an art gallery they called the Kensington Art Association. They are living there with Jearld Moldenhauer, yes, another American draft dodger, a key organizer for gay liberation in this country. In the drafty coach house in the backyard the Body Politic newspaper, the city’s first gay newspaper, and Glad Day Books, still shining after all these years – both these initiatives were begun there. The liberation politics were intersectional, they intersected, the Body Politic folks felt that it was impossible to talk about gay liberation without talking about economic liberation. What does that look like as an art project? Amerigo and Suber moved to a building just around the corner from here on John Street, and then with the help of Wintario funds bought a massive four-storey warehouse building at 15 Duncan Street. They were Marxist landlords with one of the biggest galleries in the country. The Liberal Party of Ontario was their tenant. They put on nights of dance, performance, experimental film, workshops, there was a video studio, and international art seminars. In the basement the city’s first punk club opened up, and the Funnel was given a home to run open screenings.

On the fourth floor the rhetoric heated up – was art enough? how to bring on the needed changes? – and in an issue of their home-brewed magazine, recently renamed Strike, they came out in favour of the Red Brigades, a left-wing guerilla group that had kidnapped and assassinated Italian premier Aldo Moro. The Toronto Sun, even then a reasonable voice dedicated to fairness and facts, ran this headline: Ont. Grant Supports Red Brigades Ideology: Our Taxes and Blood-Thirsty Radicals” The Councils threatened to withdraw funds, there was a House of Commons debate, everyone was running for cover. The Globe and Mail ran a cartoon with a Fidel-lookalike asking the Ontario Arts Council for money to buy bullets.

At this moment of national hysteria, the Funnel was asked to write a letter of support for their patron landlords. For the first time a meeting is held, bringing together some of the folks who had attended screenings over the past year. A collective was being born in that pressurized moment. What were they going to do? How were they going to answer the call?

It’s a good thing you all have the book and can find out.

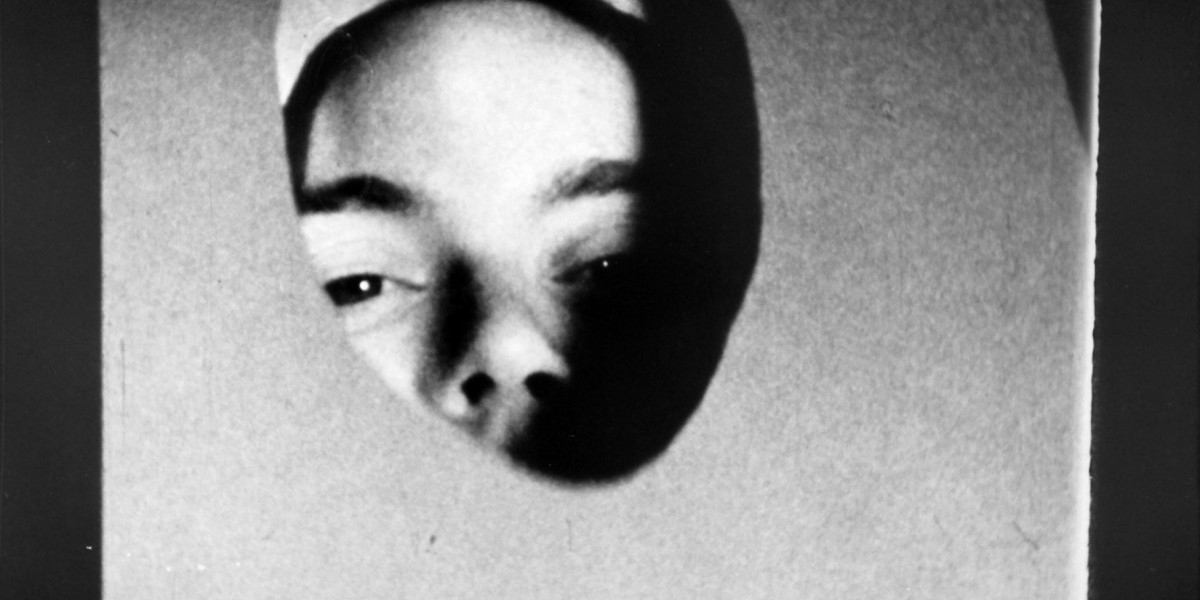

Let’s make a hard cut to the screening. We’re going to watch five movies. The Funnel had a tradition of opening each season with a member’s screening, sometimes people would be given a roll of film and asked to make something. Many movies were made as a result, the first movie we’re going to see by former equipment manager and luminous filmmaker Midi Onodera, is one of the very best.

The second film is by Peter Dudar who went on some of CEAC’s Euro treks as a performer with partner-in-crime Lily Eng. He made a series of dance/performance movies before changing direction with this dramatized account of state terror.

Annette Mangaard was part of the second wave of folks who appeared at the Funnel, where she embraced the home made, processing her own footage, or else re-viewing it using the club’s optical printer as a feminist reclamation device.

We’ll watch just one half of Judith Doyle’s Eye of the Mask, what is tonight, what is this book, if not an ode to incompleteness? Judith is an artist who has looked at the way language sticks to the body in particular ways to create a subject, but here she lights out in the middle of the revolutionary war in Nicaragua and follows a theatre troupe who is trying to marry revolutionary form and content even as the bullets fly.

We’ll close the evening with Jim Anderson. Most of his movie is silent, it shows the playful formalism that was often in evidence at the Funnel, though there is more at stake than that. It is influenced by Mike Snow’s Rameau’s Nephew, a movie that both Jim and Keith Lock worked on.

The program runs nearly 70 minutes, we’ll be back with the artists who will be happy to take your questions.

Ville – quelle ville? by Midi Onodera 4 min. 1984

DP2 by Peter Dudar 16 min, 2014

The Iconography of Venus by Annette Mangaard 5 min, 1987

Eye of the Mask (excerpt) by Judith Doyle 27 min, 1985

Canada Mini-Notes by Jim Anderson 15 min, 1974