- ABC’s of the Canon (pdf)

ABC’s of the Canon

A is for all. We can’t include it all, show it all, say everything. Because we can’t do it all we have to cut, to make a selection, to have a point of view. Because we can’t do it all we have to cut, to cut the body, and the wound is what we call the canon.

B is for behind, for all the canon leaves behind. We have constructed a domestic implement, a household appliance that is for us the image of history. It is called the toilet. The toilet is for the behind, for the past, for all that we leave behind. The toilet is a clean place, it’s a place where we convert the dirty into the clean. It is a place for making history.

C is for catch or catchy. The canon always has a hook, a connector, a sticky side, a catch. The canon is like a pop song with an unforgettable melody—the reason it stays on the charts for 800 years is that it tells us who we are, we find our own there. In the end, we may find ourselves the catch, forced to mouth the inscrutable refrains of the canon. Oh, did you see that movie last night?

D is for the dead. Most people who have lived in the world are dead. Being dead is normal, it’s the usual thing, the condition to which we all aspire. We the living are the exception while the dead are the rule. While we are alive we live amongst ghosts, images of the dead, books by dead authors. We use the canon to talk to the dead and then we use it to talk to each other, to prepare us for our own end.

E is the mark you get in school if you fail. If you are getting E’s you will never be admitted into the canon. Unless you invent something. Like Einstein. Einstein failed math because he was about to reinvent it. The old ways were useless. Now the new ways are the old ways. How many Einsteins have we already failed this year? How many Einsteins will never get beyond their poverty, or lack of education, or the crime of being born in the wrong part of the city?

F is for fifteen minutes of fame. It’s really true what they say—that in the future everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes—and this goes for everyone in the canon too—only their fifteen minutes are the ones everyone pays attention to. When yours come up everyone is busy shopping, or on the toilet, or getting ready to go out, so no one notices. It’s as if it never happened at all.

F is for fuck. Fucking the past. I figure, either I fuck the past or the past fucks me. There’s one condition however (there’s always one). You can’t use protection. You can’t use a condom when you fuck the past. Or when the past fucks you. So finally the inevitable happens. Sperm and egg meet, and a child is born. This is called history. History is what you get when you fuck the past.

G is for going back. I go back to the 16th century and find just one person alive: William Shakespeare. He is the only person I know from that time, the rest have been forced through strainers like so many impure minerals. There are some centuries where no one lived at all. I wonder if it’s possible, using the canon as a guide, to return to these unpeopled centuries and begin again.

H is for having it all, for the here and now, for heresy and history. H is for it happens, that’s all, it can’t be helped, for the history you will never write, that is being written now, while you are feeding children, or waiting in the welfare line, history is being written now while your gestures of the everyday, which you once hoped would be relentlessly scrutinized by generations to come, exist only in the moment of their becoming. Living outside the canon, even you have trouble remembering the everyday of your own life. You go to the library hoping to find your story written there, and realize instead that you will have to change the events of your life to suit the canon. To become legible. Understood.

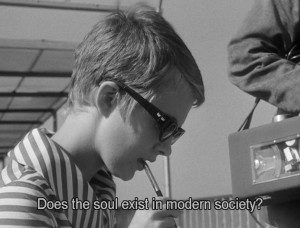

I is for identity, for the I of identity. ID therefore I am. I is the place where one person stops and another begins. It is a perimeter, a grammatical forcefield where the confused bundle of our sensations may be granted coherence. When we say I we are making a canon of one, a science of the particular—not a science founded on laws that will predict events in every case, but a science which will fashion laws which will hold true only once, in one place, a science of the particular.

J is for justice and the law, for the punishments meted out according to a semiotic morality the fathers termed a penal code. The canon is always on the side of justice, it is the word, the logos, the law, the standard by which the expressions of the everyday might be judged.

K is for Kanada, Kanadian culture, Kanadian content laws. The American cinema began without sound, but the Kanadian cinema began without images, searching in a dark others have learned to call home. How many times will we be made to relive the Vietnam war, or Watergate, or American comic books stars or American gangsters of American love? And after all this time in the dark, when it finally appears, the Kanadian cinema, will we recognize it as our own, or will it seem like a child grown strange from neglect, an accident of birth? Having cut ourselves to fit an American mirror, when we turn to face our own, is there any way we could see ourselves except as monsters?

L is for the looking glass, the mirror, our reflection. When we look into it we see ourselves. When we look into the canon we see ourselves. And for works that survive it was the same 100 years ago and 100 years before that and 100 years before that. How do these works endure? Is it because when we look back, we do so through the lens of the canon? That the canon is all that remains visible. Or is it deeper than that still? Perhaps we could say that the canon is what makes the visible visible. It is not a description of the world, or a kind of shorthand summary of times past, but the possibility of our understanding anything at all.

M is for mourning. The canon is about going back, grieving, building altars to the dead. There are some who insist that all art is a kind of mourning, a building of monuments to honour the dead world. The canon is the shape of mourning, a ritual of loss.

N is for now you see it now you don’t. For the disappearing canon. One canon slips away and another rises to take its place. The new canon inaugurates a present that extends infinitely in all directions. This is what we like now. This is what we have always liked, will always like.

O is for obla-dee obla-da, ooh baby baby—for all the nonsense that makes its way into the canon. While you slave away at another masterpiece you wonder why, the canon is already stuffed with the trivia of great minds. The canon would rather add the shopping list of an acknowledged artist than a great work by you.

P is for personal connections. For sleeping your way to the top. For writing about your friends. It’s important to understand that the canon is always made by friends. By people who drink the same beer. Laugh at the same jokes. By small communities that depend on limits, exclusion, outcasts, scapegoating. The canon makes a scapegoat of history, raising itself in the place of memory.

Q is for quotation, for reciting moments of the dead, for using our mouth to suck on the language of the past. Quotations hover between two states—between honouring the dead and necrophilia, between granting the past its due and crawling into its bed determined to fuck everything in sight.

R is for repetition. What if we only used our words once? What if our language was made up of words that were like the lines on our thumb? Unique, individual, subjective. Without repeating ourselves there’s no way to understand anything. Without repeating ourselves there’s no way to understand anything. What we are told to repeat the most: that’s the canon. The order of repetition.

S is for sorry you didn’t make it, sorry you didn’t get in, sorry there’s no room. The canon gains its strength from all those who are left out, from all the rejection notices and refusals. The canon is a class system without a middle class, either you’re in or you’re out.

T is for trying, and trying again. For: there’s always next year, you did your best, it’s not how you play it’s how… T is for the words you say when words aren’t enough.

U is for numero uno, the winner. The winner is the top ten, the favourite, the best. The winner is the survivor, the first one to cross the finish line of history, the one whose picture you can see on t-shirts and bubble gum cards, bedsheets and beer coasters, baseball hats and matchbooks. The winner is everywhere, like an elevator fart, or gas blown into a closed container, the winner expands until it covers all of the available space.

V is for vogue. For canons that may last just a few days, or a few months, or an afternoon. For canons that may be shared just between a few close friends. For canons that may be rubbed, inserted, inhaled, ingested, spread on toast or between the cheeks.

W is for the great white way. If the canon sometimes appears invisible, it is because for years it was written with white ink on white paper. In this way it assumes the condition of writing, it is the white page that makes writing visible, the glare that appears from the report of the canon, the white blast securing new territories, new lines of division. Four hundred years ago sailors took arms overseas, now we send the canon by fax modem.

X is for experimental film. What does it mean to be part of a canon of experimental film? To be at the centre of a marginal practice? I spoke to a filmmaker at this year’s festival whose film is showing in someone’s top ten list. This film has now shown three times at the festival. For six years he has worked on a new film, and when it was done he submitted it to this festival. But it was refused. The festival only wanted to show his old film. Because he is married to the past, he has already become a ghost, eaten alive by his own history. Naturally, everyone envies him his success.

Y is for why me, why her, why him, why now? Y is for the questions the canon admits, each interrogation spawning the next, until the canon appears floating in the midst of a vast query, a lonely answer in a world of questions.

Z is for Zlapotropolis—a 9 minute b/w film produced in the early part of this century by a couple of twins from Sudbury. While it was heralded at the time as an event in cinematic history that would rival the introduction of the close-up, it was lost in a freak fire and never heard of again.

Originally published in: Take One, Fall 1993 and LIFT Newsletter, Jan. 1994.