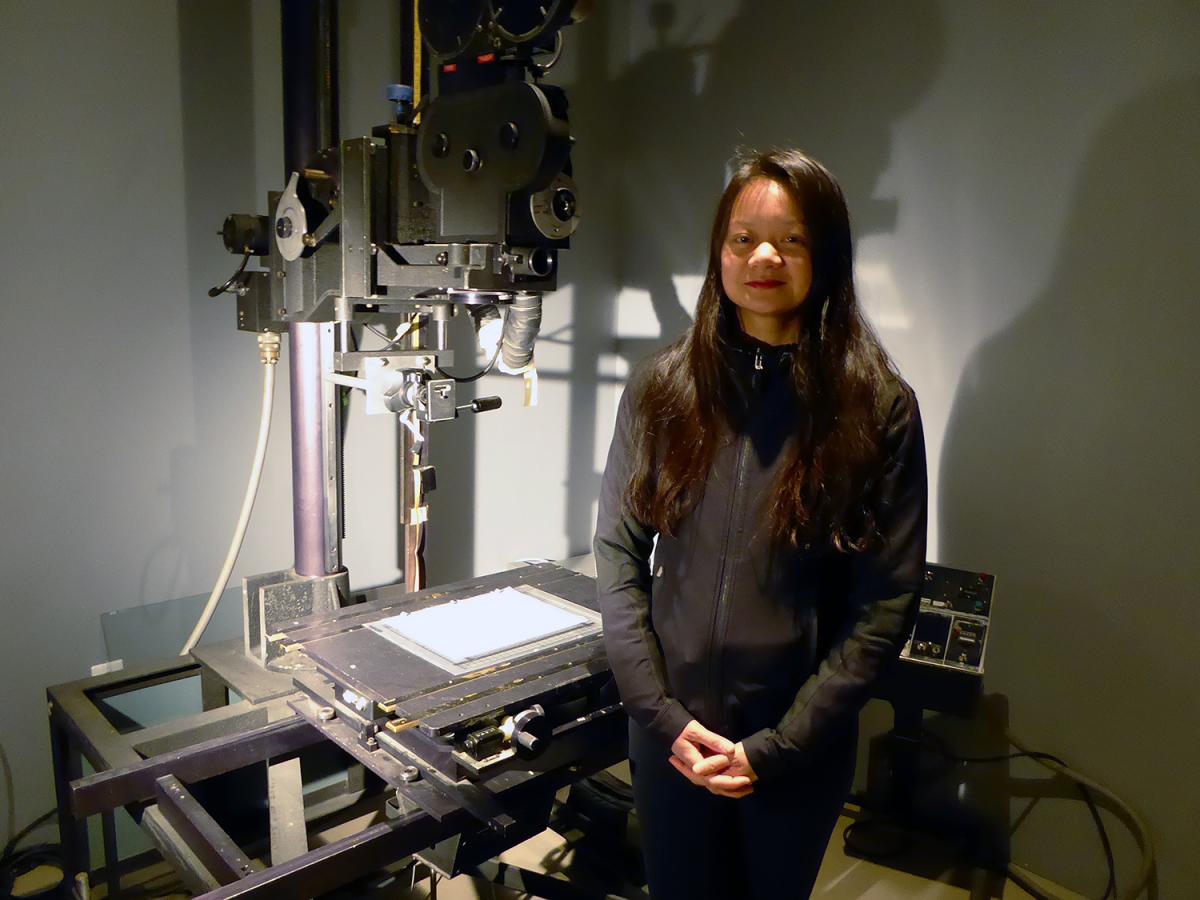

In Defence of the Poor Image. An interview with Leslie Supnet (2014)

Mike: You’ve moved to Toronto from your home in Winnipeg. In this mythically multicultural hub, the avant scene for movies remains pretty steadfastly white, I wonder if it feels like moving into an all-white neighbourhood? One of the things we white folks like to do is to project our whiteness, for instance, when it comes to making movies, we like to stuff them full of other white folks. What do you make of all this whiteness? I wonder if you could speak of your own genetic backdrop and whether you feel that impacts the work you make, the interests you have, and if you feel those interests are being fed by the new scene you’ve become part of?

Leslie: Moving to Toronto has been quite the 180 in comparison to my life in Winnipeg. I believe that the essence of the experimental film scene in Toronto runs parallel to the dominant cultural norms of the city. In terms of my living in a community, the economic and racial make-up here in The Junction where I live now is very different. While there is some diversity, the neighbourhood remains quite homogenous. The norm here is young, hip, mostly white families with children, some have Filipino nannies. One of the hip vintage furniture stores SMASH, had toy feather headdresses they gave out during a summer solstice community celebration. An Aboriginal filmmaker friend who was visiting for the Images festival asked me, “Where are all the Neechies at?” and I said I didn’t know. Winnipeg has the highest urban population of Aboriginal peoples, as well as one of the largest populations of the Filipino diaspora in Canada. Growing up for me was a mix of Filipino, Aboriginal, Portuguese, Ukranians and more, all trying to get along and make life happen.

The experimental moving image scene in Toronto is also quite homogenous with respect to curatorial taste and practices. What dominates and gets shown here belies the diversity of artists that live and work in the city. I’m unsure if the popularity of a certain kind of work (slow, structural, humorless, silent, poverty porn) has to do with just whiteness, or a combination of whiteness, maleness, and canonical value. Works that follow a trajectory of accepted aesthetics valued in the world of art is what I see a lot of in the city in terms of programming. For instance, to my knowledge, there have been no Aboriginal Canadian filmmakers shown in TIFF’s Wavelength series (an annual suite of programs dedicated to experimental movies). I hope I am wrong about this.

I am a second generation Filipino, and this part of who I am does impact my work. In the past, I didn’t colour in the hair of my characters in my drawings or animations. I was trying to universalize my drawings by leaving that blank, leaving the viewer to decide how they wanted to identify my characters. But one day someone accused me of only drawing Aryans. She actually used the word “Aryan.” Whether she knew it or not, she was accusing me of being a white supremacist. From that day on I started colouring in my characters’ hair.

I’m working on a master’s of fine arts at York University. Half my cohort are women of colour. Being in this environment has fed my interest in feminist filmmaking and figuring out a feminist filmmaking methodology. The academic scene has provided me with challenges and inspiration, in comparison to the programming here in Toronto. In Winnipeg, I was quite anti-academia and found more than enough inspiration in the artist-run community which I dearly miss. While I do appreciate the work I am able to see now that I live in a big metropolis, I realize the choices made by curators are political whether they acknowledge that or not.

Mike: Was art making a part of your childhood activities? Did you draw, scribble, dance in magic castles, perform for the neighbourhood? Are your parents forever throwing their shadows into galleries and libraries, are they also part of a regular cultural scrum?

Leslie: Art making was a large part of my life growing up. My grandfather was a carpenter and a real creative force. He always tells me this story of how I learned how to draw on a rainy day. The windows in the house were fogged up and he was holding me against the window to look outside at the rain when I began doodling on the window. I was uber shy as a kid, so drawing was a great way to keep busy. I collected Archie comics and learned to draw by tracing Betty and Veronica, and entered many of their fashion design contests, but never received a reply about my designs.

My parents tried to get me into piano so I took lessons but never practiced. My grade three teacher noticed my doodling and enrolled me into an art program at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. I was interacting with kids from different school districts, learning how to paint, draw, and do ceramics. I was terrified of the other kids, but overall it was a good learning experience. At the end of the three month program there was a curated show of the work we made. I didn’t get into that show. Perhaps this is what kept me from going to art school later. However in grade six I was in a puppetry program and our puppets went on display in the children’s play area at the Manitoba Museum as part of the Jim Henson show. My dad was with me and he was quite stoked.

It took some time for my parents to accept that I wasn’t going to be a scientist or a lawyer (my sister became a neurobiologist thankfully!), but they are thrilled I’m doing what I love now, and they enjoy my drawings and other art projects. I would constantly draw caricatures of my family and put them up on the fridge and wait for their reactions. My mother has two jobs, even to this day, and my father works evenings at a sheet metal business. They don’t have much leisure time to go to galleries, but when screenings of my work would pop up they were always there, taking time off work and being as supportive as possible. I really love them and miss them so much!

Mike: There are certain moments — can we call them “decisive” like Mr. Bresson did? — that signal a life’s turn. They often appear as catastrophe, of falling in love for instance, or losing someone. In this moment something is gained or lost, and many artists point to these as formative, not only because the necessary wounds shaped who they might be becoming, but also because they turned them towards the unlikely practice of art. Any experiences you might share in this direction?

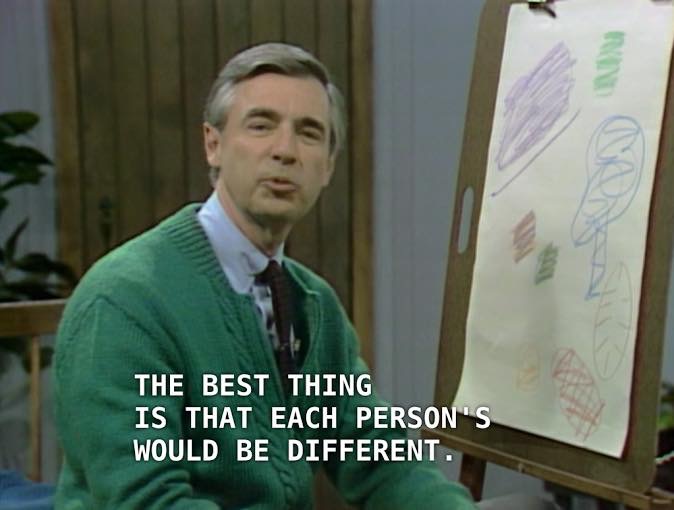

Leslie: When I was five I had one of those moments that made me turn inwards and not want to leave the house for a while. It was my second day in nursery school when another girl punched me square in the face in the hallway before entering class. I don’t remember saying or doing anything that would have instigated that, but it happened, and I was completely paralyzed with fear afterwards. I did not want to return to school. I would kick and fight and scream every morning when my parents tried to get me dressed to leave the house. On days they got me outside the front door, I would continue the fight and run back inside the house. I can’t remember how long this went on for, but they finally gave up, and I stayed at home with my grandparents and my younger brother for a while. I read, made drawings, and watched a LOT of Sesame Street and Mr. Rogers. There were so many assembly-line documentaries on Mr. Rogers — one of my favourite documentaries showed how crayons were made.

Finally after what must have been several months of skipping nursery class, the school called and let my parents know that they would have to fail me and keep me behind a year if I didn’t show up. So one day my dad told me we were going to the zoo, and that I should get ready and wear my favourite dress. My baby brother was coming along as well, and I was super pumped! I remember the dress, it was turquoise with white polka dots and had really pouffy shoulders. My grandmother was also coming along. We got into the car, all smiles, and backed out of the driveway and drove directly to the school (which was on the same street, on the same block even, so it took about one or two minutes). When my dad stopped the car in front of the school I burst into tears immediately and started screaming at the top of my lungs. At that point I couldn’t see that well with all the tears, but I remember my grandmother undoing the seatbelt, my father scooping me up and holding me tight as I tried to kick him and make a run for it. Everything was blurry, I really couldn’t see and I was out of breath. The next thing I knew I was in the classroom, and when my dad handed me over to the teacher who held me in her arms I immediately stopped the fight and gave up. I felt everyone’s eyes on me, and I was totally afraid that the girl would be there. I actually don’t know if she was, because I didn’t want to look at any of the other children, I felt embarrassed by all the kicking and screaming. And I realized I was quite late. I recall the teacher telling me it was going to be all right as she held me, and that my friends were there. She named names and pointed them out, everyone was sitting in a circle and some kids were waving at me, but I really didn’t know anybody. She sat me down in the circle, and they continued the Show and Tell I had interrupted.

Mike: Many experimentalists wind up teaching, and fringe movie shows are often attended by people who acquired the taste in school. There are certain movies and makers that have become part of the common language of fringe movies, part of a canonical history, and it’s no surprise that student work has emerged as a response to that history. What do you think about the central place of schoolings in fringe practice, does it help a living culture flourish, how have your own canonical bruisings fared?

Leslie: Before I started my master’s degree, I was working full-time during the day alongside an arts practice when I could find the time to do it, for about five years, and four years of this was when I was living in Winnipeg. Fringe filmmaking came to me outside of an academic setting. I took a circuit bending workshop (rewiring kid’s toys or synths to make glitch art or experimental/electronic sounds) at Video Pool Media Arts Centre and was introduced to artist-run culture and the moving image community which was more welcoming than the visual arts community. Since I wasn’t an alumni of the University of Manitoba School of Art, my visual arts practice was quite invisible to that scene. I really loved the spirit of the artist-run, so I took every chance I could to develop my skills through these centres. Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art (an artist-run centre) was a great place for me, that’s where I met Shawna Dempsey who offered encouragement and inspiration. The Winnipeg Film Group is where I met Dave Barber, a great champion of fringe film, and also learned from Mike Maryniuk and John Kapitany who ran workshops in experimental 16mm filmmaking, which have a direct lineage and draws inspiration from Phil Hoffman’s Independent Imaging Retreat at the Film Farm. Sol Nagler brought back what he learned at the Film Farm to Winnipeg, and started a handprocessing/personal filmmaking workshop in Winninpeg that Mike and John eventually took over. It was an eye-opening and empowering experience, I felt as if I was part of a family and heritage. There was an inclusive nature about these Winni-weirdo filmmakers and champions that I was not allowed to be part of in the visual arts community that had formed around the School of Art. In Winnipeg there isn’t a tradition of experimental filmmaking at the University of Manitoba or the University of Winnipeg, however it continues to thrive outside of academia, at the artist-run centres, in people’s basements and micro-cinemas.

In Toronto there is a lineage of fringe film, and yes student work does respond to that lineage. It flourishes here in a very different way than it does in the prairies. The work here is much more serious, and formal. There is a competitive edge here that I have not felt before. I find it mostly within a community of young male experimental filmmakers. The conversations with my peers here are different, mostly philosophical and political, whereas back home it was mostly how we were going to get things done. I feel academia does help keep fringe filmmaking alive here in Toronto, and I have more time than ever before to produce and consume as much as I can. I’m seeing work that I would never have been able to see if I was still living in Winnipeg, and I’m thinking about it differently. Perhaps the downside of such a strong lineage is how deep the grooves are, akin to a deep trench. Anyone who ventures outside the trenches runs the risk of getting hurt.

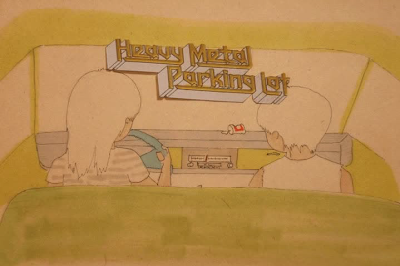

Mike: Heavy Metal Parking Lot (17 minutes 1986) is a beloved underground classic, offering up a clutch of tailgating teens adjusting their mood rings before a Judas Priest concert in Landover, Maryland. You revisit the moment in your The Animated Heavy Metal Parking Lot (1:40, 2008). Why the short form rerun?

Leslie: I took part in a remake contest at the Winnipeg Film Group. To celebrate the release of Son of Rambo (96 minutes 2007) at the Cinematheque, one of the programmers put out a call for short retakes of their favourite films. I was going to do The Sound of Music (1965), but shifted gears when I imagined how obnoxious that could be. The Animated Heavy Metal Parking Lot (2008) tied for first prize with a film by a group of filmmakers from the University of Winnipeg named Astron 6 who remade Weird Science (1985), adding an extra heavy layer of misogyny. Both our shorts played before Son of Rambo, and after the first screening there were complaints about the Weird Science remake. The complaints made it to Facebook where it became an all-out war. It got so heated that the Winnipeg Film Group decided to have a panel discussion, which wasn’t really a discussion, as Cecilia Areneda, director of the Winnipeg Film Group, didn’t allow the jury who awarded the two films a chance to speak about their decision-making process. I believe it would have cleared up a lot of misunderstanding, but they were strategically silenced. Instead, Clint Enns and I were basically ripped apart by Astron 6 and their cohort, as Cecilia took sides (intentionally or not), accusing us of encouraging censorship, which was not the case. We wanted to discuss misogyny, but censorship was the red herring, and it was quite a mess. I learned so much from that agonizing experience, which I’m completely thankful for! And TAHMPL did well on its run.

Mike: Can you talk about your animation technique? How do you do it exactly? You seem to favour single-colour backgrounds and figures (are they cut-outs?) that perform simple movements. No scene lasts too long, and proceedings are flat, all on one plane.

Leslie: I use what the industry calls “limited” animation that minimizes the amount of drawing and the gestures between keyframes. I mostly use hinged paper-cut outs, one colour background on one plane, and shoot under the camera on video. However if the work is camera-less, using scanned drawings in a software program like After Effects, I tend to draw frame-by-frame for some of it. I’m not too concerned with under-the-camera shadows or jerky movements, which are frowned upon in the animation world. That’s probably why I get more screenings in experimental/underground or microcinema programs, than animation-centred ones. I always feel a bit strange when I meet other animators, because we all know the amount of work that goes into it, though some is a lot harder than others. I had a convo with Barry Doupé once, and we decided that there are two kinds of animators — the ones who sleep and the ones who don’t. I like sleep, a lot. When I got started I had a full-time job, so this method worked well with the amount of time I could dedicate to finishing something. My illustration style is really bare bones, with characters floating in the void of negative space.

Mike: How To Care For Introverts (1:50 2010) is an emo-manual, driven by a series of voice-over instructions: “Respect their need for privacy. Never embarrass them in public. Let them observe first a new situation…” The homely, cut-out animation features a sad-eyed Asian girl sliding away from a human heap and pushing it across the floor while a butterfly hovers nearby. With the dreamy Grouper music it feels entirely sincere and ironic at the same time. Can you comment?

Leslie: I found the How to Care for Introverts text from a jpg while doing a Google image search for something. From what I could glean from reading it, it seemed like it was a parent’s guide for dealing with introverted children. While it immediately hit home, I found it really funny as well, as I looked back at my childhood. There’s a lot of noise out there, and I simultaneously feel the need to be alone a lot of the time while having the desire to connect with others. That’s where the idea for the illustration came, with the heap of sad children (it was just a drawing at first). The butterfly represents the non-verbal relationships that I value, and the blanket of clouds is a symbol for the distance needed with those who are close to me. The drawing became an installation at an animation festival in Winnipeg. It looped on a TV that stood near the children’s play area of the theatre, and I made fake brochures for parents that outlined the special needs of introverted kids.

Mike: In Spectroscopy (2:40 minutes, 2011) you draw attention to a series of coloured objects during a Winnipeg street walk, offering a sly formalist city portrait that accelerates into pure colour field alternations. It’s Mondrian as a street photographer, the hand-held shakiness of each shot adding to the off the cuff, oh it’s nothing, breezy feel of it all. I’m serious, but I’m not taking myself too seriously.

I feel something like shame in my enjoyment of this piece, as if I shouldn’t. Perhaps because I watched so much of this kind of work in my formative years, I want to throw it away, as if it is part of a past I want to leave behind, in order to make way for something urgent and fresh. It’s fun formalism, short and sweet, with an eye attuned to the way rainbows live in the bushes and trash cans.

Leslie: That’s so funny because I felt a little shame while making it! With film I still have these weird issues and anxieties about holding down the trigger for too long and exposing too much film. Maybe because I’m an animator, shooting from the hip creates tensions and shame. Also when shooting film, if I don’t have a strict plan I feel everything will fall apart. Film. I can feel the weight of its history, which is scary, but not when I’m working in video. With video I get the sense I can go infinitely in any direction. I’m happy that Spectroscopy gives a breezy feeling, since there was some spontaneity there, as I found subjects during my walk. The film itself has a weird history, as it was the first thing I made without Clint cheering me on (we had broken up in the spring), and my boyfriend at the time makes an appearance in it instead of Clint. It was made for the One Take Super 8 event, and so like with most of my One Takes, I felt the need to really structure the film, have a good plan, and stick to it since the edits are all made in camera. The first One Take Super 8 I shot was an under-the-camera animation that turned out to be completely out of focus! My heart sank as did my whole body into my seat during the screening (speaking of shame!).

On the day I shot Spectroscopy there was a street festival happening downtown, a soap box derby race that Ace Art put on, no mosquitoes to be found, lots of yard sales, people and kids all smiling and just taking it easy. I ran into Takashi Iwasaki, an artist who gave me my first gallery show and was a huge supporter early on. We found a Paul Robles-designed bike rack on Broadway Avenue. I walked by the old L’Atelier National du Manitoba space in Chinatown, one of my favourite places in Winnipeg, and took a few shots there, remembering the good times and all those who have left. I should visit home this summer!

Mike: Can you talk about your relationship with man-about-town Clint Enns? Where did you meet, how did you wind up getting together? He is credited with sound design and even editing on many of your animated trysts. Like you, he is a fringe media maker, prolifically producing short works. Rumour is that you formed a mutual encouragement society in order to become artists, as if the decision were no longer up to an individual, but needed to be made as part of a relational compact. Is it difficult having to live with each other’s successes and failures – as one of you is granted the cherished time real estate of a festival slot for instance, while the other is refused? How has living and working with an artist in the same field helped and hurt you?

Leslie: I met Clint Enns at the Royal Albert Arms, at a mediocre indie rock show. We hit it off immediately, and wound up going to a circuit bending workshop together at Video Pool Media Arts Centre not too long after we met. It was kind of a whirlwind. We became exposed to the artist-run culture of Winnipeg through media art archeology, and grew together in that vein, checking out what all these spaces had to offer. We both jumped into Video Pool and the Winnipeg Film Group. I got involved in moving images as well as printmaking at Martha Street Studio — there was so much opportunity everywhere. People and places were pretty close-knit and radicalized too. Clint has been pivotal in encouraging many people to make things, particularly those of us who are in the margins.

When he left Winnipeg a friend reckoned that Clint’s time there was like a social experiment. He brought the Winnipeg film community together to create a healthy, fun environment that didn’t take itself too seriously. For the most part being in a relationship with another fringe artist has been extremely helpful and supportive. Clint is a great editor, sound designer, and my best friend.

I don’t spend too much time thinking about festivals and screenings like I used to. I know Clint can take rejection pretty hard, which is understandable, but I feel that’s where we differ. I admire Clint’s passion for being critical, and working for change in the community. He’s very vocal and I support him when he holds the mirror up when no one wants to look. Maybe I give up too easily as I don’t believe things will change. Recently, Media City programmed a selection of works in celebration of the festival’s twentieth anniversary. Of the nine films selected, only one was made by a woman. As a response to our frustration about some of the programming Clint and I have started our own screening series called Regional Support Network, and plan on creating our own small festival to fill in the gaps.

Mike: You’ve undertaken a series of formal studies in your work. In Toronto’s greenhouse phantasia Allan Gardens (6 minutes, 2014) you lens up the plant life through a glass brightly, bending the afternoon light. In Smoke (2:09 minutes, 2014) you animate a single magazine photo of a volcano eruption, as it to disprove the old axiom that where there’s smoke, there’s fire. In Amethyst Visions (3:40 minutes, 2012), a series of brightly coloured, mostly abstract, gems and clouds, water and horses, flare in and out of the light. I’m not sure what these works are about, can you help me? Are you keeping the chops refined, working out an impulse, the way people build particular muscles in the gym?

Leslie: I made Allan Gardens and Smoke in Phil Hoffman’s process cinema class up at York during my first year of graduate work. The class was given certain restrictions with some of the assignments, and we were asked to choose from a list of constraints. I chose the edit-in-camera and manipulation of one still. We were to look at these short film assignments as doodles or sketches, as an illustrator would do to refine one’s skills through practice, to see where we feel challenged, to see how we deal with fear. So yes, these pieces acted as a way to work out some of our filmmaking muscles, to discover ones we have never used before, and to be critical of our own habits.

Smoke was the easier of the two since I deal with animation most of the time. I animated a scanned photograph of Mount Fuji about to erupt. I really like seeing the four-colour process of scanned offset printing up close, so that’s where the impulse to zoom came from. Allan Gardens was more of a challenge, overcoming that weird feeling one gets when taking out a camera and shooting outside. Though almost everyone in that space had a camera with them, shooting every flower and shrub, I still felt a bit awkward. I had different coloured glasses and Plexiglas and trinkets from the Goodwill Store to shoot through that bent the light. I stayed in the Gardens for several hours, it’s one of my favourite spaces in the city. Everything is fragrant and comfortably humid. There are couples on dates, lonely people wandering.

Amethyst Visions was made as part of a commission for POP Montreal’s Film POP programme, in which musicians playing at the fest invited film/video artists to create something for one of their songs, a music video essentially. This piece was also an exercise, making illustrations specifically for music. I chose a song by Cresting, a one man, all analog, tape musician. I wanted to keep the visuals lo-fi and dreamy like his music, so I used an ultra-macro kids camera, as well as an RCA VHS camcorder to reshoot some of the found horse scenes. Obsolete cameras and toy cameras have such beautiful qualities. The colours are always off and bleeding, the world looks so much better. In defence of the poor image!

Mike: gains + losses (3:25 minutes, 2011) feels like a very personal work. It is animated, like so much of your work, and begins with a young Asian girl sitting down to a breakfast of skull and bones. A woman’s voice sounds out as a series of scenes intercut with her unwanted meal. A boy’s chest opens and a smaller version of himself parachutes out. One girl consoles another. A bear has balloons float out of his guts. Babies protest deportation. A clock runs backwards. A boy rescues a sea ghost.

Leslie: gains + losses was supposed to be a very different movie. I received a grant from the Winnipeg Film Group for a proposal I submitted to make an animation about labour. I was going to make some kind of drawn morphing piece of people at work doing Sisyphean tasks, like a kid fixing a broken punch clock, an assembly line at a box factory, but something happened that forced me to change direction. My fifteen year old cousin, Rowie, committed suicide. I remember my mom calling me at work, weeping, and telling me over the phone, without asking me to come home right away to tell me in person. She just blurted it out in grief and I immediately fell apart. Rowie had lost her mother (my aunt) a year earlier because of kidney failure. For years and years my mother was trying to sponsor both of them to immigrate to Canada from the Philippines where they were living, to no avail, and to this day my mother feels incredible guilt about it. When Rowie died it added more guilt, pain and anger. There were a lot of thoughts about privilege and dumb luck, and why we are even in this country in the first place? gains + losses became a visual letter to Rowie, a cathartic, animation-making process. Watching it is still difficult, though it’s been some years now.

Rowie was fifteen and she looked exactly like her mother, who looked very similar to my mother. We’ve spoken to her on the phone on birthdays, Christmases, and when the family sent over money or a “balikbayan box” (literally “repatriate box”). It’s a corrugated box containing items sent by Filipinos living overseas who are called “balikbayans.” We would call to see if the clothes we sent fit, how she and her brothers were doing at school, how our other cousins were doing. We listened to their everyday experiences, like losing the roof of their house in a rainstorm, or Uncle Manny losing an eye due to illness — it was so different from our lives in Winnipeg. In every conversation we would talk about bringing them to Canada, but Rowie wasn’t as keen on leaving the Philippines as her brothers were. I totally understood. Rowie was such a happy child when her mother was still alive. There were lots of jokes and giggling. She would always talk to me in Tagalog and I would respond in English, but we could completely understand each other. It was so amazing! But after my aunt passed away, things changed. Without a mother, Rowie was teased at school. We didn’t know how depressed she was until it was too late.

Mike: Do you feel that you have social responsibilities with your work, that it’s important to represent your “community” or even friends and family? What is the point of making difficult fringe movies today, at a moment when everyone has turned into a filmmaker with their portable telephone cameras? Does it worry you that so many fringe efforts are shown only to those already in the know, they function as hipster confirmation sessions, gatherings of fandom?

Leslie: I do feel social responsibility with my work, and I’m constantly negotiating how best to make media that matters. I think artists have a huge responsibility to show the world for what it is, and communicate our unease with it. The experimental film community is a bit of a trap. While the freedom of making whatever you want is an ideal, it lacks reach. The support from the community is great and necessary at the beginnings of one’s fringe art practice, but it becomes a negative feedback loop. I came into this practice with the intent of communicating what I can’t say with words, as honestly as I can to as many human beings as possible, and it’s a constant battle weeding out what the community feels is hip at the moment (in terms of animation, that means the more abstract the better) which is largely influenced by the tastes of curators or programmers, which seems to be largely influenced by the cult of the Bolex, and the Male Genius. While I attend most of these screenings, I always keep in mind the lineage of taste, and one can’t help but look at the demographics of influential programmers and curators in North America.