Phantom Windows: an interview with Chris Kennedy (July 2017)

Mike: What is the point of artists making movies? Youtube is jammed with DIY expressions, and for those requiring more structure there’s always Netflix or even the local multiplex. What are artists adding to the cinema conversation?

Chris: I was very lucky to have the opportunity to sub in for Kevin Jerome Everson at the University of Virginia when he was on sabbatical a few years ago. Near the end of the semester, the choreographer Bill T Jones visited the school and did critique sessions and studio visits. I sat in on one for a photographer who was a student of mine. Jones asked, “Debra, with everyone able to take pictures with their cellphone, why do you continue to take photos?” I held my tongue but thought to myself, “Bill, with everyone around you moving everyday, why do you continue to dance?”

Yes, image saturation is there, but I think one of the elements of artistic endeavour is to create a sensual interpretation of the world around you and a context in which that interpretation lives. I still appreciate Scott MacDonald’s term “critical cinema” that he uses for what you call the fringe: films that reflexively question the nature of cinema (either subtly or overtly). The goal is to create another way of seeing. Definitely as a viewer, or programmer, saturation can be exhausting, but I’ve learned a hell of a lot about how to experience and understand the world from other artists.

While there are multiple ways to talk, including over loudspeakers, there’s something to be said about a niche level of engagement—a sharing around ideas and things and making them precious for a community. There is value in the intimate experience and creating alternative contexts through which to address the world and each other.

Mike: I hear you holding up the values of intimacy and community and shared values (things that are “made precious”), and how those might arrive via “another way of seeing.” For many years I was under the mistaken impression that fringe movies promoted progressive politics, open-hearted views about class, race and gender for instance. But when I crept over my fear and spoke to some of my fringe comrades I quickly learned this wasn’t the case. After a screening of Alexandra Gelis’ work, I was approached by no less than three esteemed Latino folks who thanked me for admitting Alexandra into what they perceived as the white bastion of fringe cinema. I was stunned by their remarks, which tells you something about my own racism. Do the “alternate contexts” of fringe exhibition replicate the power structures of the society that frames them? Were my interlocuters correct in naming the Toronto avant scene as a space that celebrates whiteness? What are the shared values of our community?

Chris: I grew up in a racially divided small-town in the US, so I am of course coloured by racism, no matter how well I may have been raised. Any attempt to explore beyond myself will smack against the barriers of my experience. But I also believe that it is through fringe media in Canada that I have learned how to see partly beyond those barriers. I started working at Vtape around the time the imagineNative Film & Media Arts festival started, so I learned a lot about Indigenous media then, as an example. Queer politics also intersected deeply with the scene at that moment, too, and the local production centres had a diversity of making back then. It seemed like more of an interlocked progressive time, but that may have just been my newness to the scene, when I was soaking it all in. The scene does seem to have fractured a lot since then and perhaps that’s a result of more work, more festivals and more silos. Perhaps it’s also because the fight for equal representation has a lot more impact using mainstream forms and has frankly had a lot more mainstream discussion of late—giving more spaces for filmmakers that may have been more comfortable in, or relegated to, the fringe scene before. Artists might find the small niches of experimental media lacking in reach and may be aiming for something more substantial than a gig at Pleasure Dome. Perhaps some of the niches have become more white again as a result.

On the fringe front, there are multiple fringes and there’s always exclusion and discovery. Some of the work that is made is not easy to understand on first pass, it takes a while to recognize it. There’s work that has taken me years to appreciate as a programmer and requires me to educate myself further. There’s work that I have just found out about. Add additional barriers of cultural difference, even language difference, and it is understandable things get excluded. But the great thing about fringe media is anyone can support whatever they want if they have a projector and a screen.

Mike: Can you talk about how you came to Canada, and your early impressions?

Chris: It’s a fairly simple story. My father’s family immigrated to Canada from Northern Ireland when he was ten. He grew up in Barrie and Montreal and then moved down to the States for his doctorate, met my mom and stayed. He’s a marine biologist and Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay is central to his research. While raised in the US, I have always been Canadian, with grandparents in Canada, so there was no significant displacement when I followed my sister and moved up here for university at Queen’s, met my partner, and stayed.

Mike: Were your studies at Queen’s the beginning of your life in movies, or were there earlier threads and encounters?

Chris: In high school I made two or three narrative videos for the Maryland State Media Festival using equipment borrowed from the school library’s VTR Club, which was responsible for filming school sports games. I went to university with the intent of studying and making film. While I did a lot of narrative filmmaking for the first three years, Queen’s had a bit of a focus on alternative media and Gary Kibbins provided the most direct entry point. I took his classes in visual anthropology, experimental film and video art, amplified with classes by Susan Lord. I also worked in the department one summer so I had access to their film library and watched a ton of films after hours—including some of yours. Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures (1963) was the most transformative film for me, with Farocki’s Images of the World and the Inscription of War (1989) ran a close second.

Mike: American fringe critic Michael Sicinski wrote, in a piece that you’ve linked to your website, “Chris Kennedy is an undervalued filmmaker in the experimental world, in part because, unlike so many others who stake out a particular plot of ground and till it for all it’s worth, he is a bit of a conceptual vagabond.” Do you agree?

Chris: I think that’s fairly accurate. As I’ve built a body of work, I can see that there are definite themes that course through the work, but there is a wide spread of ideas across the films. I feel more recently that I’m known for the grid films, but then I made other works concurrently, like Phantoms, that are so different. I even got a couple of responses about my new film that are like, “that’s not what you do,” when I’m thinking that it actually cleaves close to a lot of my ideas.

I’m an omnivore, so I’ve been inspired by tons of work. I’ve cited Jack Smith as a big influence, but there’s nothing of his in my work. It’s just the permission he gave towards freedom. Kaja Silverman’s interpretation of Harun Farocki’s work—the idea that we see the world through a conceptual screen—has had a huge resonance for me. I learned a ton through both your interviews and Scott MacDonald’s interviews about the range of ideas in filmmaking. I’ve been drawn to the structural materialism of the UK, particularly for their critique of representation. The films of Kurt Kren were a big influence in grad school. Robert Beavers, Ute Aurand, Kevin Jerome Everson and Nicky Hamlyn have been extremely welcoming and I’ve learned about being filmmakers from them. I’m not really part of a “school,” but I definitely hold my colleagues from my SFAI days close, especially Vanessa O’Neill and Tomonari Nishikawa.

Mike: Like too many of us, you decided to get a master’s degree in art at a slightly advanced age, opting for the San Francisco Art Institute. You made a number of shorts there, including Tape Film (5 minutes silent 2007), a single-take performance vehicle which doubles as a self-portrait. It shows you patiently applying masking tape to a piece of glass, though you seem to appear on both sides of the glass at the movie’s beginning and end. Can you talk about how your sojourn down south marked you as a maker, and your formally conceived gestures of concealing and revealing?

Chris: I got a grad degree at a slightly advanced age because I didn’t get accepted anywhere the first time, when I applied right after undergrad. In retrospect, those gap years were very important to my own development and very formative as a programmer (I programmed for the Images Festival and Pleasure Dome prior to going back to grad school). My time at SFAI was difficult (as all MFAs are) but very productive. Going to SF removed me briefly from the Toronto bubble after eight years there, both challenging me and making me homesick. The school itself was going through some rough political times ostensibly around the efficacy of art (ending in the firing of a few tenured staff—one of whom was a mentor), so there was some motivating camaraderie that glued a few of us together (especially with Vanessa O’Neill, with whom I started a weekly film salon). Most importantly, I was surrounded by visual artists constantly at work (the MFA was studio-driven rather than thesis-driven), so I made five films there.

I spent the first semester stumbling around getting my bearings. I was also economically stalled. I was spending so much on my education, how was I going to afford to make artwork? So I started working with tape—I would trace light on the floor. My colleague Seo Won Tae and I made a large installation where we traced the light from a round window as it moved across the Diego student gallery. But film-wise, I was a bit stumped.

In January, most of the MFA film students took Janis Crystal Lipzin’s two-week handprocessing class, and that was a breakthrough. We could finally make films for cheap—a couple of rolls, some chemistry, processed ourselves down in the lab (which had sinks, a printer and a contact printer, which was valuable for my other films). I learned economy. And I learned you could process clean (I never really personally embraced the bucket process aesthetic).

During the Christmas break, I dreamt that things were so bad that I was taping myself into a corner, so I took that metaphor and developed it into Tape Film. I set up a rough sequence of shooting that used all the different stocks that were available and processed each stock in the various ways I learned—positive, negative, solarized. I edited the result and had my first film in SF, made in less than two weeks for (relative) pennies. Ironically, it’s been my most popular film.

Mike: The question of geometry and human-made order haunts several of your movies. I’m thinking about your portrait of Wuppertal’s suspended monorail in Phantoms (14 minutes 2012), which also appears more slyly in the single-take street portrait Schuh Schnell Service (3 minutes 2009-2011). In Tamalpais (14 minutes 2009) and Brimstone Line (10 minutes 2013) you introduce home-made grid objects into landscapes in order to reframe them. In Simultaneous Contrast (5.5 minutes 2008) you use the serial stripes that appear in San Francisco’s bus shelters and re-view the city through them. These grids and engineered projections offer the soothing geometries of modernism, as if the world could be ordered and known after all.

Chris: I don’t quite agree with that. I am definitely addressing modernism and finding some seduction in it, but I don’t think that I’m pointing to a trust in order. If I really wanted to impose order, I would shoot digitally with a high-end camera where I could control everything, rather than with film, where fortune constantly enters. The schwebebahn, or suspended monorail, in Wuppertal is an amazing object that I was drawn to, both for its strange beauty and its weirdness, and I had a few really lovely days shooting it on regular and super 8. One could argue that it makes logical sense to put a monorail over a river that cuts through a valley—it makes even more sense if you happen to have an ownership stake in a bunch of industrial mills, as the original inventor did. However, it’s completely bizarre to encase a natural river in a caterpillar of steel. What a strange thing to do! One of the reasons I asked Ryan Kamstra to write a response text to the train was because it doesn’t take much to imagine it as some kind of sci-fi fantasy—a failed utopia—modernism and its (literal) reflection, so to speak. It has lasted for over 100 years, but it also such a strange anachronistic beast that it could be timeless.

As for the frames I’ve used for my grid-films, they’re so obviously feeble and hand-made that they immediately show how impossible it is to harness nature. We may attempt to control vision, but controlling nature (positively) is beyond our grasp. The first thing that struck me when I first travelled up Mount Tamalpais, a mountain just north of SF, is how small and distant San Francisco was. Such a vibrant city barely registered through the clouds. The grid in my film Tamalpais frames the view, but it is not a truthful frame. It’s distorted by the angle of the camera fixed on a tripod (imagine a reverse perspective with the camera/viewer as the vanishing point) so when you reconstitute the image into a picture (as I’ve done in an installation version) you get this Cubist view of the world. With that piece I was interested in dissecting narrative time—disrupting cause and effect through contiguity. Like a filmstrip, the images in the film exist after each other in time, only because they are next to each other in space. I placed the grid so that it framed up one element of the landscape in one of the 35 squares of the grid. The rest of the grid framed the other 34 shots by complete chance, without my further intervention. The grid creates an any-space-whatever and an any-time-whatever, not a definitive there.

Brimstone Line came about because David Dinnell saw Tamalpais and sent me a picture in response: a picture of grid-shaped devices in Santa Cruz that are used to scientifically measure the current. And that, in essence is what Brimstone Line tries to do—measure currents—the inevitable current of time (we’re facing upstream), the pull of the zoom (which compresses and traps vision), the movement of the filmstrip. I feel that it’s the opposite of surveying land, the field narrows and flattens but the river refuses a fixed point because it’s constantly in motion. The river flows on.

Mike: Many of your movies are not made here in the city of Toronto you call home but in the United States. Your down south portraits range from the bucolic autumn trees of Genesee (3 minutes 2011), unpeopled Northern California mountains in Tamalpais, the high-contrast traffic dodge of San Francisco’s Lombard Street in Lombard (1 minute 2007), and the Indigenous occupation of Alcatraz in lay claim to an island (13 minutes 2009). What sort of portrait of America emerges in your work? While all of your movies have documentary leanings, the more personal or political work feels like it begins with camera encounters, while in most of your work it looks like there is a strategy deployed, a formalist gameplaying or conceptual overlay.

Chris: That’s a difficult one. My relationship to America is foundational, but changing—I have almost hit that point where I have lived longer in Canada than in the US and I have a son who will grow up in Canada. However, it is extremely fertile for inspiration and I expect to find it in future films as well. Perhaps as I become more Canadian, I’ll see the US as one sees sci-fi novels—as allegories of the possibilities of decisions we may make here—but I assume it will always pull at my attention.

Films like lay claim to an island are very much fixed to my experience of the US. I found out about the Indians of All Tribes occupation of Alcatraz as a tourist, but was able to find a wealth of documents through research in the SF Public Library (where the papers produced during the occupation were transferred after the US Federal Marshals finally removed the last of the occupiers). Those documents very much directed the construction of the film—especially the letters written by an ally of the movement—someone who was sympathetic but reflective of how involved she could or should be in a movement that wasn’t her own. I’m curious whether the film resonates here now that reconciliation has become so central to the national conversation.

Most of my films come out of observations or discovery of a subject or device first, without a camera anywhere near me, and then actual research or brainstorming a structure or developing a concept. You say I deploy strategies, and yes, I do place a lot of importance on how the film takes shape and care a lot about editing. That is done occasionally by executing a preconceived conceptual structure, but it is often more through organically working with the material (narrative ordering is also a conceptual structure, after all).

I travel with a super 8 camera and sometimes a Bolex, but that very seldom initiates a film—only Jane’s Window (10.5 minutes silent 2005) and Towards a Vanishing Point (8 minutes 2012) contain footage shot prior to concept. There’s a pile of footage at home that is waiting for me to hit on a creative use—there needs to be adequate friction with another image or idea for a vignette to become something more, just as there are ideas that require the appropriate image to bring them to fruition. Towards a Vanishing Point and the acrobat both were held in suspense until there was that appropriate friction, waiting for elements to coalesce around an idea. For Towards a Vanishing Point, Saul Anton’s imagined conversation between Andy Warhol and Robert Smithson (in his book, Warhol’s Dream), made sense of images I took at an oasis in Egypt, a pyramid in Mexico and a found home movie of a telescope—each of which pointed me to the idea of longing. For the acrobat, the film came together when I learned that footage I had bought from John Kneller was of the longshoreman’s strike in San Francisco. This discovery happened in parallel with my frustrations with some of the political posturing at SFAI—the images and the Ryan Kamstra text I used help me articulate a film that used gravity as a metaphor.

Mike: Jane’s Window feels like your more personal work, and it’s one of the earliest movies you list on your filmography. It’s a moving portrait of your grandmother, filled with quickly observed visual phrases offering details of a room or a face, intercut with visits to a Japanese monastery and Chinese sites, where she spent her childhood. Your partner Sarah appears as part of a lineage of women; painting a wooden horse. Can you talk about how the movie took shape, and why you decided not to continue in this lyrical diary mode of making?

Chris: Jane’s Window came about because I was shooting a lot of diary material as I learned filmmaking, partly to learn the camera, partly to experience that side of being a filmmaker. It took shape after my maternal grandparents passed away and I wanted to remember them and honour their creativity (they were both artists and the house was built by my grandfather). I had a much larger amount of diary footage at that time, but it was only after I centred it on Jane and used the window as a metaphor that the shape of the film truly came into focus. Being raised abroad opened her, and opened me through her influence. Although I still shoot when I can, I stopped making diary films because, frankly, my life isn’t that interesting and more importantly, I don’t really want to make my life interesting in order to make interesting diary films. I’m impressed with people who are able to do that, but I’m more comfortable approaching subject matter at more of a remove. I may still do work that touches on my grandparents’ past, but it won’t be in the lyrical diary mode.

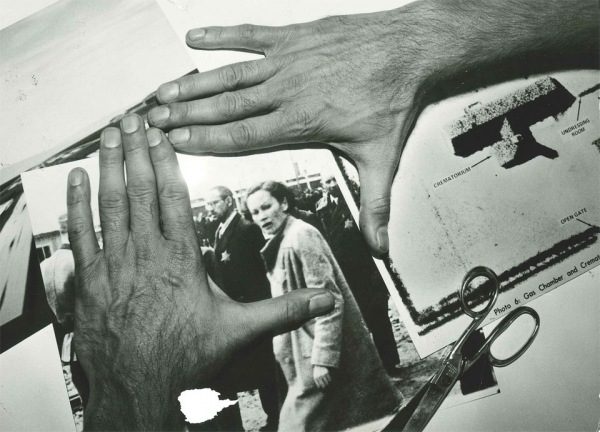

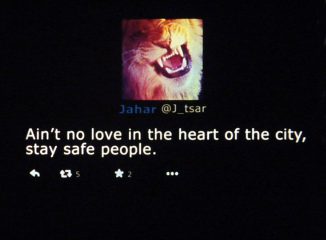

Mike: In Watching the Detectives (35 minutes 2017) you present Reddit and 4chan sites dedicated to re-picturing crowd scenes from the Boston Marathon of April 2013 where two home-made bombs killed three people, and injured hundreds. Why this subject? How did you structure the movie? And why is it a silent 16mm movie?

Chris: I’ve always been interested in how context is constructed through images (you can see similar interests in my earlier film Memo to Pic Desk that I made with Anna van der Meulen in 2006). When I learned about the findbostonbombers conversation thread on Reddit, I was immediately drawn to it. I watched it unfold in real time a few days after the bombing. The redditors would zero in on somebody—literally circle them—and create a narrative around why this person was a likely suspect, until something came along to debunk it. As usual, people’s pre-conceived notions of who is a likely suspect came to play (pointing to our inherent biases and racism), but the construction of believability was also fascinating to watch. For a few minutes, something would become the truth before being declared false.

This material speaks about how we deal with images and information in this era of saturation and shaming. The thread was shut down about a week after it started after complaints about its efficacy and ethics, so it took me awhile to find the texts again. When I did, it was a matter of paring down the long conversation threads to their essence and sequencing them along a comprehensive, narrative timeline. In effect, it was about flattening a bunch of simultaneous conversations into a cinematic sequence. It is very much a narrative movie, and a film about narrative.

I transferred it to 16mm for a number of reasons. Transferring the digital images and texts reintroduced an organic sense of time to the experience, there’s an inherent movement that makes it feel less like a slide show. But transferring it to 16mm did a few more important things for me. It rescued it from the internet, making a case for the real life shared experience again. It reinforces the theatrical experiences and makes us—the audience, the material and the artist—accountable to each other. The internet is filled with atomized individuality and I didn’t want people to experience the film in that way—I wanted us to work through the ideas together. Finally, transferring to film stripped the images of their metadata—in a film about surveillance, I thought it was important to remove elements of surveillance culture that are inherent to the computer—the ultimate forensic traceability of the image.

Mike: Much of your work foregrounds formal concerns—especially questions of framing and the structuring of experience. I’m wondering if you could respond to (former Images Fest artistic director) Amy Fung’s bracing definition of “entitled aesthetics,” and how your work resists or accommodates these tendencies.

Amy: “…So much of what I see harkens back to a legacy of experimental artists and their works and aesthetics from the 60s and 70s… By this term, entitled aesthetics, I am speaking to the lineage-chasing artists and curators who choose to regurgitate canonical aesthetics from decades past. Entitled aesthetics inbreeds a type of navel gazer who does not understand that aesthetics are time-sensitive tangents born of socio-historical contexts. For the genre of experimental cinema, like Abstract Expressionism in painting, or like Beat poetry in literature, the canon has been filled by a very narrow demographic that benefited from a post-war condition that turned towards abstraction in form and content as a reflection of the world, and at the base of this, of course, is a systematically racist, sexist, and ableist society. It wasn’t only white men doing these things, but only they are celebrated and remembered, and as a result, continually re-hashed to stretch their legacies further.” (http://postspecificpost.tumblr.com/page/5)

Chris: I see Amy Fung’s framing as an extension of a longstanding paradigm—a lineage even—of arguing about the relative merits of various types of work and whether historical aesthetic practices are “time-sensitive” and politically efficacious (or are even valid in their time). I had a similar argument ten years ago at SFAI with Okwui Enwezor about the future and value of analogue filmmaking. I’m sure if I talked with him now, he’d share my surprise about the resurgence of analogue filmmaking these last few years. Unfortunately, my argument with Enwezor preceded the firing of someone I cared deeply about, something that also repeated itself in the context of Fung’s article. Policing aesthetics is a tricky area, especially for a curator of a festival with such a broad mandate, but her specific statements have a long history and I’m on all sides of the issues they invoke.

In reference specifically to the term “entitled aesthetics” and the postwar condition: The New American Cinema, of which US experimental cinema emerged from, was started and fostered, in large part, by Jews and other displaced people escaping the Holocaust and Soviet or Japanese occupation—people like Maya Deren, Amos Vogel, Jonas Mekas and Nam June Paik. I’ve always understood part of the urge to create archives and lineages came from the fact that these artists had to flee with barely a suitcase—they had to reclaim a history. Later, the larger experimental scene included people like Jack Smith, Warren Sonbert, Marlon Riggs, Barbara Hammer—queer artists who were very much pushing against the status quo. As a straight white ango-saxon Protestant, I am thankful to have these and many other people to inspire me with their work, to teach me the possibilities of radical culture and to help me question myself.

I do agree that even these scenes were part of a racist, sexist and ableist larger society and that participants in these scenes, to this day, suffer from all the ills of regular society with a few extra ills thrown in for good measure. My grandfather’s own behaviour taught me that artists should not be role models. And yes, lineages come and go for good and ill—it was always amusing to watch New York’s now extinct Views of the Avant-Garde from afar. Lineages of teachers and students were so blatant you could draw a hereditary kinship chart—although I don’t question the deservedness of many of those artists to show their work in that environment. Despite those agreements, I do think that there are possibilities in this project, that we can open it up, and the mere calling out of certain “aesthetics” is not only vague but limiting—as in her follow up poem when Fung calls out an Indonesian artist for being interested in Christian Metz. Why shut down this possible conversation? It undermines many new makers as well as parallel histories that are coming to more general knowledge and are being amplified. It also forgets that experimental filmmaking is such a peripheral form in and of itself that the ultimate rewards of “lineage-chasing” are so very, very low.

Amy was stirring things up, perhaps more than she expected, but I think there’s other ways to frame the larger argument. Deirdre Logue, hand-processor extraordinaire and lesbian herstorian, who was heavily feted at this year’s festival, put things a little more kindly, “How do we both resist and reconcile our participation in this oppressive system?” I think learning from our many forerunners, with an understanding of their failings and ours, can’t hurt.

Mike: You have been a very active programming presence in the city for many years now, currently you are curating TIFF’s year-long Wavelengths series, and co-running Early Monthly Segments with Scott Miller Berry. I’m wondering if you could talk about how your views on programming have changed across the years. Do you feel that programmers have responsibilities to the local community of makers (who often make up most of the audience)? There are some who feel that the small number of programming portals should be more widely shared, and of course there are new collective formations blooming in response to already established structures. Should there be time limits on how long one can be the artistic director of the Images Fest, or working at TIFF?

Chris: First about longevity: Susan Oxtoby was an important presence here in Toronto for years. As a programmer who was a part of the institution of the Cinematheque Ontario (now TIFF Cinematheque), she was able to build a platform for local work as well as build longstanding international relationships that helped her champion experimental work within the context of cinephilia. There is currently no one in a position like Susan’s—institutionally supported and able to fully use that institution’s resources to further the field—even Andrea Picard (TIFF programmer) is on contract, as am I. Mike, you have also, over the course of your career, moved in and out of programming roles and the local audience and community have benefited from your long-established links to an international network of fringe filmmaking, and you do it largely for free. Other city scenes also have one or two people of longevity that allows them to do certain things that younger programmers may not have the resources to do. I’m thinking of people like Steve Seid, Kathy Geritz and Steve Polta that helped historicize an otherwise fluid and volatile community in the Bay Area. It’s actually remarkable that we don’t have anyone more institutionally enabled to do this in such an equally active place. It makes sustaining Canadian programming practice very difficult and limits our ability to bring Canadian work to an international field as well. It hobbles us.

Beyond my four years at Images and five years on a small contract with TIFF, most of my programming has been volunteer, so I understand why those specific jobs may be coveted, but the solution isn’t term limits. That also does us a disservice. Haven’t complaints about recent artistic directors of the Images Festival been that they didn’t know the local scene at the start of their terms (maybe they’re even openly hostile to it) and it took them a while to settle in (thankfully with the help of programmers who were a little bit more abreast of things)?

Kate MacKay, Scott Miller Berry and I started Early Monthly Segments almost ten years ago because we thought the Toronto scene was a little staid at the time—we thought Pleasure Dome wasn’t as active as they could be and there wasn’t much else. I had come back from San Francisco where there was a huge history of screening collectives and you sometimes had to choose between two experimental screenings in one night! I had started a weekly screening salon in SF with my colleague Vanessa O’Neill, so I was pretty inspired by that energy when I returned to Toronto. Kate and I were not programming anywhere at that time (we both got our programming gigs a year or two later) and Scott was only doing administrative work at Images, so EMS was our outlet. We did one Indiegogo campaign for our Warren Sonbert series in year three, but otherwise never applied for funding. We pay expenses from the door and chip in a little extra ourselves. So when I hear there isn’t enough this or that, my first response is: “start your own.”

Now there are a lot more collectives: Vertical Features, MDFF, Colectivo Toronto, CONVERsalon, Ad Hoc, Vector, re:assemblage, Regional Support Network, so there’s more happening again. Maybe when the Commons@401 and TMAC finally get up to speed there’ll be more institutional options too.

In terms of responsibility to local makers, Pleasure Dome has started to take a leading role on local filmmakers again—the subtext behind the film/video kerfuffle at New Toronto Works a few years back was really, “why are local filmmakers only shown in New Toronto Works?” and I think the last two years of programming has done a lot to address that. With my role at TIFF Cinematheque, I see it as using the resources of a large institution to bring in stuff that would otherwise not be seen so that we can make films in a larger context. I’m constantly paying attention to what’s being shown in Toronto and making sure I can augment it in my role. I do show local work, and I submit that many people may think that I don’t show enough, but I think an international context is something we should strive for. I also think the audience for TIFF Cinematheque is not only the local maker scene, but the general film-going audience and the more I can open that audience up to experimental filmmaking, the better for us all. Toronto can be fairly parochial. Every year at Images there’s the local screening at 7pm on Saturday night where everyone comes out. They all leave before the 9pm screening, which invariably has one or two international guests staring at 20 people in the audience where just a few minutes ago there had been 150. While it’s important to champion our own (and there are many ways besides programming I do this), it’s also important to be curious beyond ourselves. Building an ecosystem of multiple venues and programming visions is one of those ways.

Mike: How has becoming a father changed your work as an artist, and as a programmer?

Chris: It gave me a better sense of priorities. In all honesty, having something concrete to partially distract me from the arguments that have rocked the arts community in the past few years has been a blessing. It’s also the first time in my adult life I’ve had peers from outside the art world—fellow parents—which is also helpful for a sense of perspective.

I’m still very much committed to this type of filmmaking and the scenes it intersects with. Programming and administration are as important to me as my filmmaking and more time consuming. It’s been difficult to balance everything over the past four years, and it hasn’t all gone smoothly. But as excuses go as to why I can’t be as productive as I might want to be, I’m glad to have this one.