When I was just a little boy

I washed up mother’s dishes

I stuck a finger in my eye

And pulled out golden fishes

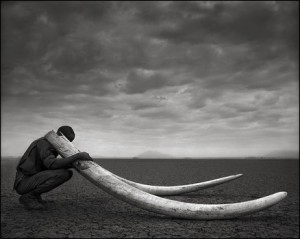

When I was young I had a recurring dream of the salmon run, genes fired with a mating rush that sent us leaping over the banal and commonplace, looking for a place to call home. I always found it in those days, and as I dropped my eggs I imagined my parents inside, twin avatars of mutual destruction, waiting for the current to cool so they could begin again the genetic warfare we call family. “You have my nose,” he would cry, “Those are my lips,” she would add, looking me over like a spare parts shop—here was the first time I would stand with the body’s perimeter shattered, its wrap of flesh and tissue a mask of history.

My body seemed like one of those past-their-expiry-dates models designed for those too young to be horrified about nostalgia. Like the Volkswagon or the Pope. This is how I learned to live in the body granted me by my parents, as if on loan it seemed to me, as I scanned its surface for a trace of uncles long dead—as a compact of partners, a consensus of generations, the visible arrangement of history.

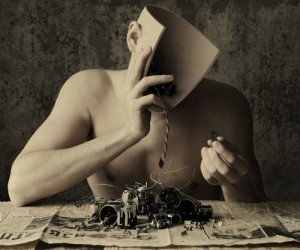

The feeling I got when told I had Aunt Becky’s chin and Arthur’s hands returned to me as a filmmaker without warning one evening. It was at a screening with friends, I’d invited them for our monthly mutual congratulation society, no pleasure quite like being told what you already know. Or hope you know. When along came this stranger, Jim or Arnold or Mathew, the name is blurry now, how did he get there I wonder, already beginning to regret the whole evening. After sweating through a montage that seemed breathless in the editing suite but which now seemed more suitable for an audience of sunning reptiles, oh no, don’t worry, we’ve got all day, and besides, the flies here are delicious. After receiving the obligatory congratulations of my comrades the stranger remarked that my work seemed a warmed-over version of Brakhage. “Brakhage!”, I shrieked, “Like fern and bracken?” Was my precious meisterwork being compared to the nodding fronds of the natural order? The ambient luster of roadside detritus? Unsure of where I stood I took the only course open under the circumstances. I stalled. Quoted outdated stats from The Marxist Review. Issued apocalyptic warnings about immanent widespread ruin if this film was not well received. And then he piped up—No, no, I had it all wrong. Brakhage was a filmmaker just like me, grand American poobah of the avant-garde, you know a little shaky camera, a little shake’n’ bake editing, batches of out-of-focus stuff with important sounding titles. I could only nod. He was smiling by now and holding out his hands. Look, they seemed to say, I like Stan Brakhage, and you’re just like him. Spitting image. So there it was. Happening again. My body—this time a body of work—was asked to imagine its origins elsewhere, its construction a necrophiliac’s catalogue of tasty parts. Warmed over, hadn’t heard that phrase before, surely that couldn’t be optimal.

That’s when I noticed the rot and realized what it was—the smell of history returning. Of course I could hardly keep Marx’s snappy little dictum off the playback machine—that everything in history appears twice—the first time as tragedy, the second as farce. And it didn’t take a genius to figure out which end of the stick I was teething on. Or for that matter anyone I knew. All working in the mortuaries of the avant-garde—brushing aside the boxocosis populi to lick on a hairy old dick, its mortified shaft grown pestilent with misuse but nonetheless yes, sure enough, there beneath the foreskin, there was a little trace, a little spot of the magic jam that’s transported this one to the palace of kings. I figure if I keep licking at this rate in ten, maybe twenty years I’ll have my ticket. Sure it smells bad, but I always think, look at what they run on television every night. Just goes to show you. People can get used to anything.

Originally published in: “Is Dead?” film catalogue of Pinhole Cinema, Seattle Washington on Feb. 2, 1993 — a retrospective program of American avant-garde film from the 1960s