Mindfulness

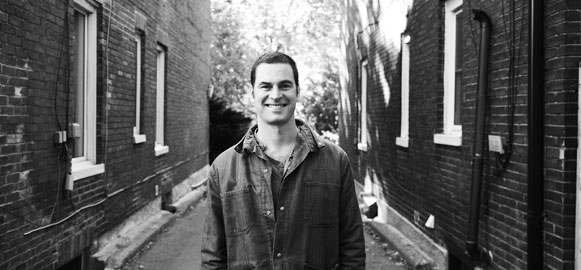

Awake in the World (by Michael Stone) book launch

Shambhala Centre, Toronto June 9, 2011

It’s such a pleasure to be here, here in this beautiful room with you. I think that every room has a nervous system in it, certainly a skeleton and frame, and I can feel in this room the endless hours of dedication and silence and sitting. Can you feel all of that quiet gathered in the muscle memory of this room? It’s a room that’s easy to say yes to, like a beautiful groom – oh yes please I’d like another one just like him – like a beautiful bride. There are some rooms that are easy to say yes to, and for a couple of years I thought I would dedicate my entire practice to room like this, to faces like yours, to eating ice cream. So pleasurable, so many flavours, especially when you’re being mindful. But one day the ice cream ran out, one day even ice cream wasn’t ice cream any more, and worse than that my best friend wasn’t my best friend anymore. How do you sit in the difficult rooms of your life, when things aren’t rolling in your direction, when everyone you’ve ever met calls you up just so they can say, “No. I’m sorry, not you, never.”

On Tuesday evenings, a shifting collection of folks gather on Bellwoods or Queen Street or in the alleyways in Parkdale and practice yoga, and sit in silence, and study the dharma of old books. This year it’s been The Lotus Sutra, and if it hadn’t been written 21 centuries ago, you’d swear it was the 60s again. At the Centre of Gravity we’re trying to learn how to sit in the rooms we like, and we’re trying to learn how to sit in the rooms we don’t like. One of Michael’s favourite sayings is “the heart of the practice.” Perhaps the heart of the practice is simply saying yes to whatever room we’re in.

I think we’re practicing yoga because the surgical strike that separates mind from body — that sees the mind as some kind of precious Tiffany diamond carried around by the meat — this description hasn’t been very helpful. We’re making pilgrimages inside our bodies, inside our lives, and sometimes our meaningful wandering takes us to books like this one. It’s called Awake in the World. It’s Michael’s fourth book in as many years, and offers a kind of greatest hits collection of talks delivered all over the world in the last five years. On nearly every page I can hear Patanjali, the Homer of the Yoga-dharma world, whispering into his ears. It’s a book about why you might practice, and how to practice. It’s a book that unpacks in very clear ways the grounds of Yoga and Buddhist psychologies, and it’s a book about a father and a son. Sometimes we need a book to teach us, and sometimes a six year old boy, and sometimes it’s the way rain falls on a window or the way the traffic on Bloor Street suddenly appears as music. The book looks into suicide and breathing, into rain forests and radical love, never offering a program or prescription, it’s not a book that’s been chiseled out of stone, out of Michael’s stone, but that’s taken shape as a series of questions that are always opening. Please join me in welcoming Michael Stone.

Mindfulness and Ethics by Michael Stone (2011)

Three Levels

Today we’re going to explore the relationship between awareness and morality or mindfulness and ethics. There are three different levels of ethics – there is the literal level, there is the compassionate level and then there is the koan level, meaning the level where you have a practice that allows you to become the situation. You could say the first level is about having a practice, the second level is about your practice including other people, and the third level is recognizing that you are others. You are the interdependent web that we call life. It’s easy to get stuck in one particular perspective. The nice thing about these three lenses is that they allow us to constantly re-see or re-present what we’re facing.

Language

One of the terms that’s thrown around a lot these days is mindfulness. The word comes from the Buddhist tradition, in Pali the word is sati. The same word in Sankrit (which you find in texts like The Yoga Sutra by Patanjali) is smrti. Sanskrit predates Pali, it was a language in ancient India that was mostly used by the Brahmin class, so when the Buddha’s teachings were starting to be warehoused via memorization and eventually codified into texts they were laid out in Pali because it was more of a street language. It was a daily language in common use, not reserved for temple chants or Brahmin families. And of course Pali was a language that women spoke, while Sanskrit remained largely in the domain of men. Some scholars think that it’s possible the language of Pali was created for the Buddha’s teaching — this is a tangent we’re not going to follow, but it’s interesting to imagine languages created to appeal to a living situation. This is a nice thing to remember about spiritual practice, that the great traditions that we are referring to are invented by humans. They’ve been designed and re-designed, and as some of these teachings come into our culture, they may have some important things to teach us, and at the same time our psyche and our society are going to change the teachings. This is a good thing. The way we wrestle with ethical principles like non-violence and honesty is how these teachings come into our life. We struggle with them, we act them out, we integrate them, and this is really the process of embodying the precepts.

Sati or smrti literally means “to remember.” It’s a verb meaning “to remember, to come back.” And that’s why it’s translated as mindfulness because it’s a technique of coming back to present experience. It means coming back to this moment, coming back and arriving in your body, in your heart, in the conditions that you’re in.

Two Wings

The practice of mindfulness really has two different wings. We could say that the practice of meditation has two different wings, one wing is called shamata, which is usually translated as calming. The other wing is called vipassana. Vi means to go in and passa is an eye. Literally it means insight. One side is calming and the other wing is insight and they work together.

Sitting

When you sit down, you drop your sit bones down onto the floor and give the earth your weight and let your legs feel the floor beneath you. Sometimes, if my nervous system is very agitated or my mind is busy, I’ll spend some time feeling the stillness of the floor. The ground is always quiet. And then starting to follow my breathing, I’ll give attention to the inhale and the exhale. Sometimes I’ll focus on the breath in my nostrils, and sometimes it’s easier to feel the breath in the belly. This first stage of shamata is being able to let the calmness of the breath spread in the body, and let the body receive the breath.

This doesn’t mean making your breath calm, it’s important when we start to practice formal meditation that we’re not confusing it with the yogic breathing techniques that we call pranayama. What we’re actually doing is letting the breath be natural, and giving attention to the breath and observing in the nostrils if the breath is smooth like silk or rough like canvas, if the breath is more in one nostril or in the other nostril, if the diaphragm moves more to the front of the body, or the back of the body. You can allow the breath to come and go, really trusting your body. Your body knows how to breathe. When the body starts breathing there’s a natural lift in the base of the skull, there’s a sense of being awake and alive and uplifted by the breath. It’s energizing and yet it’s calming at the same time. There’s a sense that we’re awake and also at ease.

The term mindfulness is interesting in relation to shamata because the word sham is where we get the word shanti (or peace). Sham is actually a name for Shiva, and the word shanti literally means ease. It’s a noun and a verb, so it means to feel a sense of ease and also to ease fixations.

So the first sense of shamata, or the first step of mindfulness, or the first step of finding ease, is just to be able to stop. To know how to stop. Our culture is running so fast, we’re all running. Some of us are running away from things we don’t want to look at, running away from stillness or interdependence. And even though intimacy is something we might value, maybe there are ways we’re running away from intimacy by not knowing how to stop, and to be in this moment. The way the sun is coming in the window, the sounds in the room, the feelings in the body, the digestion in the belly, the warmth right now in my legs. When we come into the body in this particular moment we can appreciate that the nature of mind is awareness. Behind what we call the mind, behind all these stories and images and sensations that we’re forever shuffling around in new arrangements, there is a sense of awareness operating all the time. I like to think of this as a natural resource. Being able to trust that place of presence is something available at every moment, even when you’re panicking and stirred up, and the way to find that place is through the breath.

Under the Mind

If you sit still and anxiety is present, or restlessness and agitation, or maybe it’s early in the morning when you sit and you’re tired, don’t try to use your mind to work out what’s going on for you. Instead, go under the mind, or go to the other end of the spectrum, to the body, to feel and trust the body breathing. Sometimes people who haven’t processed deep grief, or undigested traumas, have a hard time connecting to the feeling of breathing in the body, so just go slow. You’re not trying to make a particular experience happen.

Let’s say you sit and you want to follow your breathing but there’s a lot of restlessness. Just notice restlessness while you’re breathing. In other words, you can bring mindfulness to whatever’s present. Mindfulness doesn’t mean that you’re aware of breathing and nothing else. If your mind is busy you can note: mind is busy. If you’re planning you can note planning. If you’re feeling lazy notice laziness, but stay with it and watch how it changes as you connect it with your breathing. When we call meditation “mindfulness” or “shamata” we’re engaged in a practice of stopping in order to be present with whatever arises: our compulsions and fears, our worries and sadness. And by giving these states attention, whatever we’re caught up in settles. This is the sham, the ease.

There is a physiology of ease, a sham of the body. When the soft palette lifts, when the mouth is lifting, in yoga this is called shambhavi mudra, or the gesture of ease. As we release our grip on what we’re thinking about, or what we’re obsessed with, there’s a physiological response through the soft palette, and in the heart, where there’s a kind of openness. It’s a practice that creates a space. When you’re really caught up in something and you’re following your breath, eventually whatever you’ve been hooked by passes away because it’s impermanent, and its passing leaves a space. It might last just one moment before something else arises, but there is a gap between compulsions. This gap is the core of non-harming. It is the impulse of non-violence in the world. To be able to find enough quietude in your body that you can start to see the arising and passing away of thoughts allows you to touch this place of non-harming.

Physically embodying the practice of non-harming is different than swearing allegiance to a philosophy of non-violence, it grounds sometimes abstract ideals into whatever’s happening right now. How can we cultivate the ability to touch that place of non-violence where we’re connecting with the breath at the level of sensation and allowing the conceptual mind to settle in an undistracted and impeccable awareness? This relaxed attention is the place where we start to get a sense of the interconnectedness of life. The difficulties in our lives tend to make us self-centered. It’s my pain, my worry, my distress. In these states our minds tend to ruminate on the past (“If only I had…”) or project into the future (rehearsals, planning). The first thing that leaves is a sense of generosity. How can I give anything to you when I’m in so much pain? This is really the paradox of meditation, we might start sitting imagining that it’s going to give us peace, or send us into a space where we won’t have to be bothered by those pesky feelings anymore, but what starts to arrive via the technique of staying with the breath is a sense of ease. This sham, this ease, is behind the scenes all the time, it’s not something that has to be achieved or earned.

This sense of ease is called shamata, that’s the beginning of one wing of meditation. When things settle then the other wing starts to show up, and this is the wing of vipassana which means insight. We start to get insight into the workings of our mind, into the way that suffering is constructed in our experience and in our society. Simply put, the more stillness you can contact in your own heart, the more you begin to see how whatever you’re sticking to, whatever you’re going after, whatever you’re trying to keep for yourself, is pretty much a futile endeavour. When you see the futility of that you begin to get some insight into dukka or suffering. You gain insight into the ache that’s always trying to be covered over and that is social action. As soon as you make the link between how you’re acting out unconscious patterns of behaviour, or how you’re not able to connect with stillness in your own self, then you’re contributing something profound to the culture. Your friends and family will feel this. Meditation is not really so solitary, it benefits everybody. Part of the vipassana side of meditation is to start to see how suffering is something we’re running away from. The Buddha urges us to fully know suffering, he called it the first noble truth. To fully know violence. To fully know how you kill. To fully know how you feel when you’re unsatisfied. And then you learn how to take care of that unsatisfaction, or sense of lack or inadequacy or however it shows up for you in different circumstances. We’re trying to learn how to take care of our unwanted feelings.

Impermanence

As vipassana continues we start to have insight into impermanence, how everything that moves through awareness is subject to change. It’s flowing. In fact the “I,” I think I am, is also changing and impermanent. The third level of vipassana is called emptiness or not-self. I’m not going to get too much into that today, but essentially it’s referring to the fact that underneath all the distractions and ideations and picture thoughts we touch something different than who we think we are, and the felt sense of that is what I would call intimacy or the oneness of life or interdependence.

Judge

So it’s important when you’re caught up in something to have a kind of relaxed awareness about it, where you’re not judging what’s showing up, and then returning to the breath and letting whatever is predominant come and go and returning to the body as your anchor. As this happens you’ll start to notice the places where it’s easy to be present, and on the other hand there will be certain patterns and sensations where it’s really hard to stay present. This inner work you’re doing is the beginning of non-violence. It engages all three levels of non-violence at once. It’s literally not causing harm because you’re not acting out of unconscious, habitual and reactive roots, you’re not running away from what you feel. It’s compassionate because at each moment you’re showing up accompanied by your breathing. It belongs to the koan level because you are yolked to your experience, you are with your experience as it is happening.

There’s a wonderful joke in meditation circles that your mind is like a bad neighbourhood that you don’t want to go into alone. How true is this? Some corners of our minds are threatening to us, we don’t really give some areas of our life too much attention. Meditation will bring up these areas, and so we use this simple practice of following the breath, we go into those neighbourhoods accompanied by the effortlessness of breathing. Even when we encounter parts of the psyche that are threatening or difficult, the breath is as loyal as a really good friend that never leaves you.

Home

The practice of mindfulness meditation is a practice of coming home. It’s a practice of arriving. If we can’t arrive and meet each moment then ethics is just good philosophy, or it’s discipline, neither of which is really the heart of what we’re working towards. So let’s say that our practice right now of non-violence will be the creative engagement with each moment as it is. If you can’t meet what’s going on for you moment to moment to moment, you lose track of yourself, you lose track of your life and you’re unable to hear the oneness of life. This practice is about the loving response that happens naturally when we’re not stressed, or highly reactive or projecting our suffering onto institutions, politicians, our teachers, our children. Our practice sings when we’re able to stay with the truth of what’s happening in our experience. I hope you can see how being mindful day to day is inseparable from ethics. I like to call this situational ethics. Situational ethics means having the ability or creativity present, as a wellspring, to meet any situation. To be able to drop your fixed view. This is the heart of non-attachment. Non-attachment is a skill that’s not so different from learning to play the piano, or speak a foreign language. We’re training our brains, our nerves, our breathing, to be able to show up. I don’t think you can separate creativity and non-violence. I think they both come back to this ability to meet the moment fully without prejudice. When you can really meet conditions as they arise you are practicing non-harm. You’re practicing creativity.

Sometimes when I sit I like to start with a reminder that I’m setting the intention to be present without judgment about whatever’s going to come up for the next thirty minutes. I set the timer where I can’t see it, I trust it to be the container that will hold the experience. Whatever shows up in that time container, whatever shows up in that room, whatever shows up in the whole field of awareness, I am present with it, with the breath in the background. And if I get too caught up in something, I’ll just come back again to the feeling of breathing.

Off the Cushion

At the end of sitting meditation I like to bow, and then before I get up off my cushion I’ll sometimes review the sit and ask: where was I caught? Was there something strong I was invested in, or something I may need to give attention to? I’ll just note it without a lot of elaboration or judgment and then I’ll get up. Sometimes meditation reveals areas of our life that we need to give attention to, and we don’t want to just leave them on the cushion. Oh, there’s a lot of sound in the digestive system today, I need to eat really simply. Or: I’m feeling stiff and I really should have a bath. Perhaps the instinct of self-care is an extension of non-judgment when we’re quiet in the meditation practice.

Relationships are the key to yoga, relationships are the doorway to the dharma. But to be in relationship honestly and courageously we need a practice that allows us to be in our lives. To be who we are. Mindfulness meditation is smrti or sati, the practice of coming back, the practice of returning, returning to your life. This is my life: loneliness, I can be one with that. This is my life right now: loud construction at the corner. This is my life right now: hunger. I can be one with hunger. This is my life right now: so excited for the weekend. It’s the last day of the week, I can’t wait to have a break. To be one with that, to feel happy, to be joyful. And then to watch as every sensation passes. Shamata is about stopping whatever we think should be going on (How is my life supposed to be right now?) and arrive at the way that it is right now.

Non-violence

Meditation means making a commitment to really work with the nature of your mind. And most of the time when stuff comes up like an emotion or pain in the body or relationship trouble we start analyzing it, thinking it through, trying to work out our emotional life. In meditation we’re not using that part of the mind to get hold of things, we’re opening up to our lives and being intimate with whatever’s going on. If there’s restlessness, there’s restlessness. You can be mindful of anything, and as soon as you’re mindful you’re present again.

If you try to get rid of restlessness or anxiety it’s actually violent. It’s actually himsa, it’s killing because you’re killing the actual life of your body and mind. If you’re able to face your agitation in an upright, tender and respectful way you’ll see deeper layers of life. The precept of not killing really comes alive in formal meditation practice. Everything that comes up in your practice is your life. If you’re gentle in the midst of what is happening, you can bring that gentleness to other parts of your life, and of course, you can extend that quality of softness to others.

It’s a practice of non-violence because we’re becoming non-violence. This isn’t accomplished by restraining the impulse to cause harm, but to take qualities like busyness out from behind us and exposing them to awareness. When we sit still and observe the impulses to get up and get away, we might recognize that if we had some space around these habits we could wake up more and more. Being busy and not getting to the cushion is not your fault. To meditate is to get underneath that a little bit. Meditation practice can be happening all the time.

Meditation is the heart of non-violence. When you exhale, that space at the end of a thought, that space is where creativity comes from. That space is where improvised responsiveness comes from, that’s the space where your heart needs to go before your thoughts get hold of what you should do. All ideologies come from top down thinking and so do ethics that are too stiff, or Victorian rules. How can we find the connection between what we touch in our meditation practice and ethics? Non-killing has to do with converting your reactivity into a more tender zone, and that takes training, just like learning a language does.

Underneath

We meditate so that we don’t have to create more suffering for ourselves even if suffering is present. We can also come home to suffering, to fully know suffering, our own and the suffering of others. We can be sensitive and tender to the suffering of others because that person is also you. And then this brings the other wing, vipassana or insight. We start to get under how we think and see without the prejudice that comes from our unconscious. This is not easy and it’s not hard. It is a daily practice that you can take up to benefit all beings. You might think at the beginning that meditation is just for you, but you’ll see over time how calling mindfulness practice the heart of non-violence is activating the practice in your own heart, and in the body, and in the body politic. All is one. So please be courageous and share with your partners, they too are aspiring bodhisattvas and Buddhas.

Centre of Gravity

Michael Stone talk April 20, 2010

Yoga Sutra chapter 2 intro

Consciousness is not a thing, but is conditioned, impermanent, dependently arising. It is dependent on making contact with an object. There are six kinds of consciousness:

Nose, skin, tongue, ear, eye, mind consciousness.

When a sense organ contacts a sense object it creates consciousness.

Then there is a sensation.

Then there is vedana: feeling. There are two kinds of feeling: raja (attachment, desire to repeat pleasurable experience), dvesa (aversion, desire to move away from what is not pleasurable). These terms are twins, they are part of each other. Raja is already dvesa, dvesa already raja.

The problem is not the big cravings/aversions, the problem is the millions of small cravings/diversions, the ones happening each second, over and over.

After sense organ-sense object, then sensation, then feeling, then asmita (ahs me tah), the storyteller, the I-maker, superimposes I on the situation. You can’t have story of yourself without attachment or aversion. If you have a pain in ‘your’ foot, there is a deep feeling before it becomes ‘your’ pain. I am always the main character of my story. Even while dreaming. Jung understood the ego as a defense complex. Its first function: to like or dislike, he said that before liking or disliking, there is no ego.

You create yourself in every moment of perception.

The problem with storytelling is that it ages. It gets stale, it loops.

After asmita, abinivesa: fear of collapse of story of me. In every moment of experience, in every moment, I’m dying. “I” doesn’t have the reality that sensation has. “I” is a virtual life of imagination. Because we can’t control physical reality, we try to control metaphysical reality.

When any culture creates language, religion is created, symbols can be made, because we are sufficiently divorced from real experience.

For some: spectrum of feeling is very tight. Can’t allow themselves to be too happy, or too melancholy. The practice of yoga expands range of what you feel. Asana practice: learn discipline and consistency, and the container of awareness broadens. Can feel more range and subtlety: not so quick to label our feelings.

When you’re fully in your life you don’t see it.

Asmita, the I-maker: creates a being (me) outside of space and time that is going through all this, but the storyteller can never be grounded. The self is a fiction. Instead of clinging to this fiction, we can become creatively engaged with our lives, instead of living out unconscious plots. Storytelling that is chronic prevents us from feeling. How to strive for a life of love, attunement and eccentricity. Situational ethics. Creative responses without need for overarching laws and precepts.