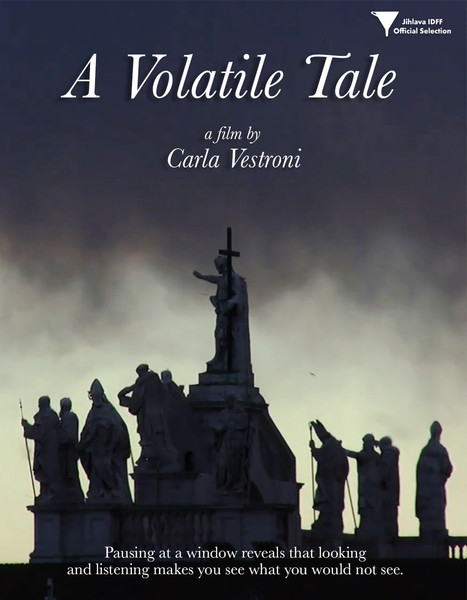

A volatile tale by Carla Vestroni

Originally published in Festival Daily, Jihlava International Documentary Festival, 2017

It’s so difficult to leave my universe of an apartment, when I walk to the end of the world I arrive at my kitchen. But here, in this shelter and solitude, the artist takes up the task of philosophy, posing her central question not once but twice at the movie’s opening in order to frame proceedings: “The thinking that gets you nowhere takes you everywhere. All other thinking is done on tracks and in the end there is always the depot or the round-house.” In other words – linear thinking actually goes round in repeating circles, or else is garbage. The question is: how to do the kind of thinking, or even make the kind of movie, that gets us nowhere, so that we can be everywhere?

It’s a large fantasy: to be everywhere. In order to be everywhere the artist films only from her window in Rome for an entire year in order to conjure A Volatile Tale (44 minutes 2017). The view from her window offers her shadows, crosses and urban gulls most of all. Rooftops. She looks at Greenaway’s A Walk Through H: The Reincarnation of an Ornithologist (1978) through her computer window. Are we watching a dialogue of windows? Conversations with friends drop casual philosophical asides. “It’s interesting how you can look without seeing.”

This movie is also part of the sub-genre of city films (Vertov, Ruttmann, Marker), except that instead of the expansive digressiveness of most work in the field, here the view is extremely restricted, as if the entire city could arrive via the act of narrowing one’s view to a single plane, and finding within that place everything. Perhaps this movie is modelling for us the kind of nowhere thinking that offers a portal to everywhere.

There is a necessary cover story the artist offers up for her steadfast vigil. An urban gull has given birth on a neighbour’s rooftop. How could she have missed such an epochal event? Determined to maintain surveillance, a maximal coverage, she sets up a camera in her window, waiting for new life to appear. Her waiting becomes a necessary ground for the unexpected, the chance encounters that are at the heart of this movie, this kind of seeing. Perhaps even: this kind of life.

The looking is never a long take. Instead, like the birds that are her preoccupation (the central characters in this dramatic interlude), the camera searches in short clips, grazing across a roof before cutting to a neighbour’s window, or offering quick scenes of gull interactions. In place of the joys of duration: short sentences.

And it’s important to note that the window is always open. Friends come to visit and flow into freewheeling conversation, often commenting on the view in warm tones of intimacy. Perhaps the decision not to leave the apartment is at the same time an invitation for the city to enter it. Nothing must be left out, nothing and no one. My home is your home.

Next door the nuns brush their endless hair, or sit in groups and hang out. They have also reframed their life by expressing their faith in an architecture that will change their views, keep them aligned with larger forces. Perhaps this looking is also a form of prayer, which we maintain by assembling in the dark, our heads raised to the light cast on the cinema/church windows. We gather in public so that we can be alone, alone together, and return to a place of public looking so that we can lose our direction, our certainties, and feel the world enter us again.