The Government was Kaput: an interview with Andrew James Paterson (2015)

Mike: While video artists often appear in their own works, they are usually quick to insist that they are not actors. Instead, they are performing, though sometimes they have cast themselves, not to mention friends and familiars, in dramatic roles with costumes and sets. Could you elaborate on the difference between acting and performing in video?

Andrew: Video “acting” has been an ongoing subject/concern that never quite goes away. There are some who even feel that narrative is making a comeback. Concerns about acting calibre came into play in the early eighties art boom, when both video and performance art became sidelined by the painting boom of the time. How could video and performance compete or become credible commodities? Well, since many of the proto-Canadian video artists were and still are also writers, dramatic elements began to predominate. Video seemed more professional if it more closely referenced its ghost mediums (television and/or film). Similarly, performance came to be seen and evaluated in reference to proscenium theatre or cabaret.

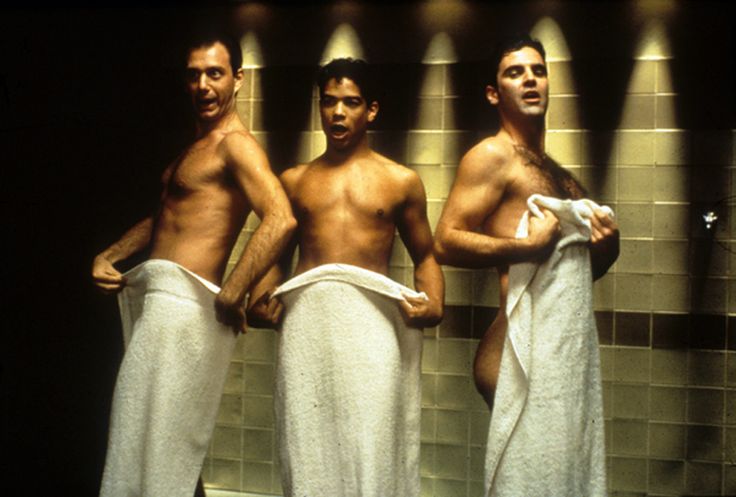

In many tapes of the eighties and early nineties, one can see a shift away from groups of friends performing, toward dramatized scenarios with often uneasy mixtures of artists and professional actors (or artists consciously or unconsciously mimicking professional actors). Some of this tension becomes apparent in relation to the writing of scripts. Are these supposed to be matrixed or non-matrixed performers? (“Matrixed” refers to depth of characterization, both physically and psychologically. “Non-matrixed” refers to strictly visual images. One can recognize a cowboy by his hat and that is all that’s required.) Not all of the performers in these narrative videotapes (my collaboration with Jorge Lozano—Hygiene (42 minutes 1985)—is one of many examples) function in the same mode. This could either be an amusing subtext, or an incoherent mess of intentions.

The question of “real time” is interesting. I think “real time” is rather seventies and even sixties. Early Fassbinder and Andy Warhol come to mind. Warhol’s motif of Anybody Can Be A Star is also important in the context of proto-video-art. Members of a scene or a ““community”” both usurp and critique stardom and glamour. Needless to say, the Warhol clan never required certificates from The National Theatre School or the New York Method Actors’ Studio. Some viewers found this work, and its video art successors, tough sledding owing to its slowness.

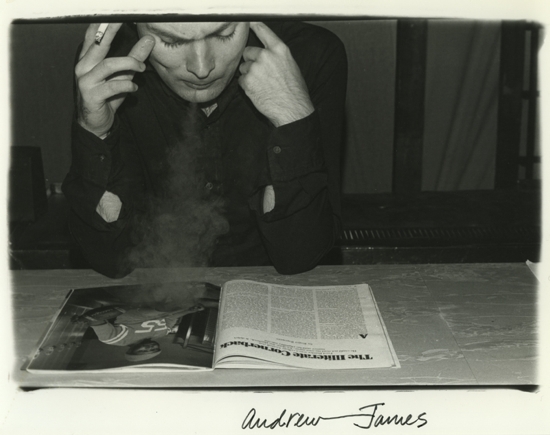

The relationship between words and pictures is also relevant here. Video largely concerned with flash surface and quasi-MTV editing tended to avoid words. Words were for people who could not make pictures. Videos filled with words tended to avoid quick editing, or even any editing at all. In entrepreneurial trade fair circles (Video Culture Canada – 1983) “content” was denigrated because it contained too many words and not enough visual pizzazz. One of the organizers of Visual Culture Canada described content as a smokescreen for technical illiteracy.

But, in the context of the early-eighties art boom, video (and performance) artists often found themselves mimicking their host mediums. Increased professionalism was in demand (or perceived to be in demand), and that involved higher production values, which included a higher grade of performers, which led to an uneasy mixture of performers and professional actors. Ironically, many of the professional actors recruited for narrative videotapes were from the theatre, and tended to act as if on stage rather than in front of a camera. By contrast, the self-performers tended to appear more relaxed and at home with the video medium. They were, after all, generally being themselves (when they felt they were expected to act, that was another story).

There is another ghost at play here, not a ghost medium, but a ghost genre. The genre of documentary (or self-documentary). One might consider the dual meanings of the verb “testify;” either to be a witness or a performer. These are not necessarily contradictory, and smart documentary practices acknowledge this duality. Because many performers in superficially dramatic videotapes are not really acting (either because they can’t or because they don’t even make an attempt), these works are closer to a documentary mode. A scene or “community” is busy documenting itself.

Ah yes. Activism. If one browses the Purchase Collection catalogue for Trinity Square Video between 1982 and 1991, one will notice many collected video art works that tend to eschew formal/formalist premises in favour of a sort of naturalist drama, marked by an often strident concern with being “political.” Here again one finds a blurriness between what is acting and simply self-presentation, but also usually devoid of artifice (or humour?). Many of these kitchen-sinkish videos are arguably not intended to be read as “art” works but, rather, communiqués to or documentations of, various political moments or sub-communities.

It is interesting that many of these tapes deploy a soap-opera format—the daytime rather than prime-time variety. An obvious canonical precedent here would be Lisa Steele’s The Gloria Tapes (55 minutes 1980), which initially confused many art denizens with its foregrounding of feminist and socio-economic issues, even though the strength of Steele’s performance distinguished this important body of work from movie-of-the-week television. Colin Campbell’s dramatic ensemble tapes of the early to mid-eighties are also carried by the artist’s idiosyncratic performances and the witty insightfulness of his writing. But not all contemporaries and/or students were so successful.

Here we come to the embarrassment or cringe factor. Oh my God, what was I thinking? Many video artists active in the eighties and nineties now look back at these works with embarrassment at the “bad acting,” the shrill and strident political correctness, the emphasis on text at the expense of visual inventiveness. I confess to submitting my tape Pink In Public (20 minutes 1993) to a program at Available Light in Ottawa aptly titled Video Barf. Before responding to their call for submissions, I watched the tape and I thought it wasn’t a complete embarrassment. But it is flawed and dated, and some of my embarrassment derives from the fact that I now work in a very different mode (although I have recently used other performers’ voices, if not their bodies and faces). Some of it comes from the fact that this tape (and also the aforementioned Hygiene) are so much of their time, and thus of limited or strictly archival interest. Directorial and editorial strategies which seemed like uneasy compromises now just seem wrong-headed.

Embarrassment and gossip are not-so-distant cousins. There can be vindictive humour at the discovery that a highly rigorous formalist once made industry calling-cards barely disguised as politically-correct, kitchen-sink dramas. Auterist critics could have a field day with artists (both authors and supportive “actors”) whose presence is commonplace in videotapes in a certain time-frame. I have donned priestly wardrobes in at least some of my performative works (okay, I have a priest fetish!), and have performed cameos in other artists’ work, often as an authority figure of sorts. Does this reveal something about me? Well, maybe yes and maybe no.

Archivist researchers may indeed uncover works that have not been suppressed but have certainly been gathering dust. Perhaps artists did not remove these works from distribution simply because nobody ever rents them. There is a thin line between artists disowning works by deleting them from active distribution and artists who assume that their back catalogue is only of minimal interest to completists and other trivia queens or obsessives. However, historically-themed exhibitions are hardly unusual. So… is an artist who deletes components of his or her back catalogue a control-freak, a pompous modernist who still believes in the sanctity of authorial intention and interpretation? Are such artists ridiculously concerned with their own legacies? Well, yes and no.

Mike: I recently attended a Vito Acconci retrospective at the Stedelijk, and was surprised to find his expansive oeuvres in writing, video and architecture crammed into a series of rooms (and self-built pods). A single space might contain four or five long tapes, or more. It was a riot of simultaneity, and seemed designed to discourage exactly the kind of attention required to sit down and watch someone talking “in real time” as Acconci did so often when he was busy, along with some few others, creating the foundations of the art 40 long years ago. Here the work was rendered invisible through its act of exhibition, a not uncommon occurrence. I’m wondering if you could spare some words on the subject of “duration,” a gravity-filled term which comes quickly to mind whenever someone mentions the dreaded phrase “video art.” For most it means: edit-free broadcast that doesn’t know when to stop. Television without the remote control.

Andrew: Yes, video and duration. “Real” time as opposed to dramatic time. Or as opposed to rapid-eye movement or associative montage.

When I first made my own initial tentative video forays, there was a sharp division between those working in “real” time and those wishing to be big and modern and new. “Real” time concerns came from performance and body sculpture. With my theatrical and musical background, I was quite familiar with complaints against real time from those committed to dramatic time. This derision of slowness arrived from video art’s ghost mediums of film and television. Although now we have a surfeit of Reality TV, which is surely the idiot son of durational video-art.

There is a rather awkward transition between solo-performer works (or self-documentary) and quasi-dramatic works using a soap-opera format. Daytime soaps like Coronation Street are the model, using editing to move from character to character, though the pacing remains slow. Warhol is another precursor to artists’ videotapes which deploy friends of the artist in quasi-dramatic roles. Viewers witness a scene, or “community” that is self-documenting. Artists cheerfully, but dutifully, appear in each other’s documents. Viewers either get it or feel excluded.

In the mid-70s, new cameras carried the possibility of working in colour, and brought artists closer to the real worlds of film and television. Artists were obliged to maintain production values, so out with real time and bad lighting and bad acting. Many established artists, and some beginners like myself, self-consciously tried to up the ante and make credible filmic or television-referent works, even if we were unlikely to achieve broadcast. There were tapes that did television very well—like General Idea’s Test Tube (28:15 minutes 1979) and many of the tapes in Television by Artists, which was produced by Trinity Square Video in 1980. Some high-profile videos were not only conceived and edited in reference to broadcast, there were tapes that directly quoted and thus appropriated television. For example, Dara Birnbaum’s Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (5:45 minutes 1978). Some argued that they were critiques or interventions; others thought they were merely regurgitated television.

I remember working as an actor in Eric Metcalfe and Dana Atchley’s Steel and Flesh (12 minutes 1980) at the Western Front in Vancouver. Eric thought I was a Canadian Peter Lorre-figure, like in Fritz Lang’s movie M. The tape was based on Eric’s drawings so dialogue was reduced to spoken captions and used only when absolutely necessary. This was considered an affront to the slow-paced and highly verbal Toronto video scene.

Mike, your observations about the Acconci retrospective at the Stedelijk… I feel there is a difference between “film” and “art.” I know this is a tiresome debate that is unresolvable, but there are different time-frames at play. Watching videos or films in their actual time is so often not on for gallery goers. That is what is done in the cinema. Most of what plays in galleries involves looping, compressing, or freezing time. But with Acconci’s Tower of Babel presentation, is a large and significant body of work being reduced to a sort of one-stop-shopping?

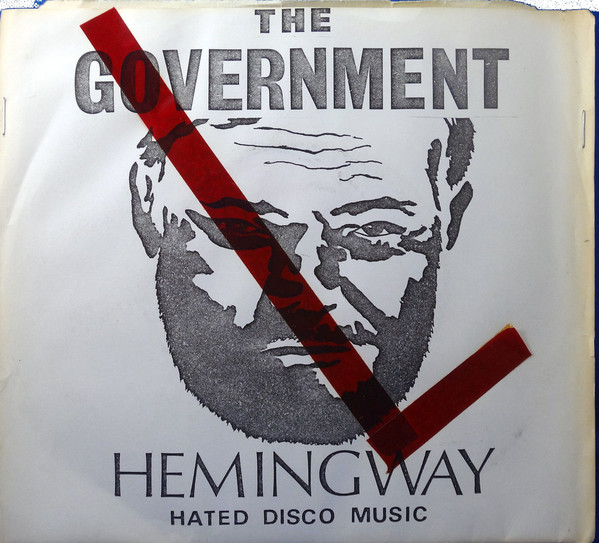

Mike: In the late 1970s you started up a fabled art band trio named The Government. You wrote, sang and played guitar. Can you talk about the band’s beginnings and its intersection with the art scene (were you already part of it?)? Why didn’t you want to be stadium rockers making the big money?

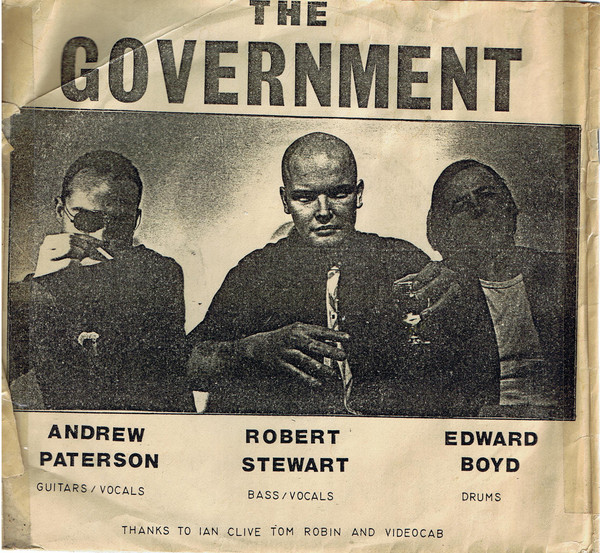

Andrew: The band was formed in 1977 and it initially consisted of myself, Robert Stewart on bass, vocals, and some writing, and a drummer named Patrice Desbiens (a Francophone poet). We came together as a house band for VideoCabaret, who in those days were an intermedia theatre/video/live music aggregation. I had previously been doing live music for this company, in a different band with Michael Brook playing guitar. (Michael Brook, along with Rodney Werden, co-founded A Space Video, which became Charles Street Video, a video production centre for artists.) Michael Hollingsworth was a playwright and co-director of VideoCabaret. We were friends and he needed a band for his play Punc Rok, so I put the Government together. We were trying out different names and not really settling on one, until Marion Lewis of the Hummer Sisters (who were also co-directors of VideoCabaret) kept calling us The Government as characters/musicians in the production that we were writing music for and performing in. We gave in and went with the name. So… there was an incipient confusion between whether we were the VideoCabaret house band or an actual band.

There was a fascination with punk within the Toronto art world, and we were and then were not part of that scene. VideoCab were and weren’t part of an art scene. They were more rooted in the theatre. But The Government, particularly Robert and myself, became friends with video artists like Randy and Berenicci, Susan Britton, Rodney Werden. We’d wind up at the same parties as General Idea and David Buchan and Colin Campbell. Being around video artists, and live video, made me think about using the medium myself. I think I tended, even then, to be rather formal about video because of my interests in film and writing. I had pretensions to being an actor, and not just a musician. But I preferred performing to a live camera rather than an audience. I enjoyed the mediation of technology. This went along with Robert and I being at least as interested in ambient music (or wallpaper or bathtub music) as we were in song structures. I was obsessed with Brian Eno and Robert Fripp.

The Electric Eye was the Hollingsworth production that created The Government. For myself it was primarily a curiosity item for a particular art crowd. It featured the band not only performing live, but also interacting with characters/actors in a pre-recorded videotape. Clive Robertson, then of Centrefold and Arton’s Publishing, wanted to record Electric Eye as an audio cassette, and it wound up as a long-player. Clive saw Electric Eye as performance art. He saw me, in particular, as a budding performance artist, while Michael Hollingsworth and VideoCab saw the focus being on the taped actors with the band as live accompanists. By the time the album was released, we’d severed with Hollingsworth and VideoCabaret. Hollingsworth felt VideoCab weren’t properly credited, and since it had developed under their auspices, he was technically correct. Now it would make more sense to record the thing as a performance-DVD. But I was asleep at the wheel. I should have realized that Robertson and Hollingsworth were never going to mesh very well. I used to be more optimistic about these things.

I saw The Talking Heads at the A Space Gallery in 1977 and in the art school the following night. They were only a three-piece then, and they intrigued me. They were the opposite of punks. They were so normal that they had to be perverse. This, for me, was much more interesting than so many of the punkers—so many of whom were old rockers with their hair cut short. The Heads took the so-normal-we’re-not thing very far indeed. One of my initial resistances to the name The Government was the Heads song Don’t Worry About the Government, which was the diametric opposite of Anarchy in the U.K. and London’s Burning and so many more. Another reservation I had about the name was the fact that we were employees of a company that were heavily dependent upon government grants. 30 years ago, there was a huge schism between people inside or outside of the grant system, and this fault line continues to exist. I received my first small Canada Council project grant when the Government was fairly high-profile, though I felt I lived in a different world than most musicians, let alone the club promoters. So… I guess I had entered an art world.

But the definition of an art band… it’s almost arbitrary. In Toronto there were the OCAD (Ontario College of Art and Design) bands like The Dishes and The Biffs and then T.B.A. Their looks fell somewhere between preppy and mod and they sounded clean. They were suburban—no improvisation, no messy noise. The Government were more quasi-New York hipster; there was some improvisation and quite a bit of noise. We liked “free jazz.” We were urban, although we started getting a suburban audience that wasn’t from an art milieu. There were two other drummers—Ed Boyd and then Billy Bryans—who both changed our sound, which was what we wanted to do. But with too many things flying at us from different directions, we lost our bearing. Did we wish to cater to a more suburban geeky audience, or were we paranoid about losing our art credibility? Shit happened concerning our recordings, of which there were five. I think I can speak for Robert Stewart as well as myself, although I don’t know his current whereabouts. We were suspicious of anybody attempting to mould us or make us over—which makes us sound like modernists or something even more reactionary. If we had attempted to streamline ourselves, then how would we have gone about it? Perhaps added a better singer, at least one other more conventional musician, or commissioned outside writers? It’s all hypothetical. I don’t think either Robert or I had the right temperaments. We were suspicious of many of the people we encountered in “the business,” and our suspicions were usually quite justified. Shit happened. I think The Government got stuck in a nether zone of sorts, between large auditoriums and art bars or clubs. I felt uncomfortable playing in larger venues, either for people who didn’t know what to expect, or for people who had predetermined notions of what they were expecting. That is the pop business: people pay to hear the hits. So, either you go with the flow, or you act out, or cop out. I guess that’s what I ultimately did, although we let the band fall apart without being premeditated about it.

Mike: I wonder if you might riff on the queer underlining of the budding art scenes you are describing. Glenn Schellenberg, keyboard player for ur-Queen Street band The Dishes, said that the young and fabulous on both sides of the microphone were looking for a place to share the late hours. Though removed from the heat in boystown, a suite of art bar migrations (Beverley, Cabana, Cameron, Gladstone) have offered up public spaces for queer hopes in the west end. The Government was also part of that, wasn’t it, particularly at The Cabana Room?

Andrew: The Cabana Room was really an extension of the Beverley Tavern scene, which had been THE de facto art school bar. At the Beverley there’d be a mixture of art students (many of whom played in bands), artists, and gay activists. The Body Politic (gay newspaper), Art Metropole (home to General Idea), and FUSE were around the corner. In 1978 charges were laid against The Body Politic over Gerald Hannon’s article about boys loving men loving boys, and there had also been a raid against The Barracks (a nearby bathhouse). There was a lot of interesting mixing at the Beverley. Sound didn’t carry very well from the stage at the front end to the social space at the elevated back or north end, so people could chatter and gossip independently of the bands. The Beverley is immortalized in Colin Campbell’s video Modern Love (90 minutes 1978).

The Cabana Room was launched in the summer of 1979 by Susan Britton and a guy named Robin Wall whose current whereabouts I don’t know. The programming mixed bands, videos, and performance—often on the same evening. Later on it evolved into more of a music bar, in the conventional sense of that description. This was after Colin Campbell’s Bad Girls (65 minutes 1980) video was shot and shown in the bar. I was in New York with the band when that was going on, thinking about relocating. However, we came back, and remained part of the Cabana scene, although we were blamed in some quarters for the demise of the original space. One of our records was getting radio airplay and thus attracting this rather creepy, straight-geek-record-nerd audience. They were mostly male and not very social. Not at all like David Buchan’s Geek Chic. Ed Boyd, The Government’s drummer, didn’t like playing there because too many of our friends were on the guest list to make much money. Later on, we actually titled an LP Guest List. It was not the most welcome of records, it bombed.

Certainly the initial Cabana blend was rather queer, or at least hospitable to queer elements. I think we’re talking queer and not necessarily gay, although many of the central players were gay, bi or bent. There was a gender-fuck going on; a good night at The Cabana Room could indeed be polymorphous. It was, initially at least, a safe scene to play in. It was some distance from the gay club or disco scene, but also from the straight music bar scene. The Cabana Room was fun in a way that, say, The Edge or Edgerton’s (Toronto’s prime new wave and punk venue) wasn’t. A band could mix in other media like video and performance, although this all started to confuse the music geeks who came down just for the bands. Perhaps not completely ironically, shit also happened within the art world, and this shit was pretty much the end of the Cabana Room being perceived as a safe venue for performers (female, queer) and not just another yahoo bar.

By the time of the massive baths raids of 1981, the Cabana Room was still a default bar for many downtown artists’ activities, but many others had moved on. It was an ancestor of today’s Gladstone Hotel, or possibly the earliest days of The Cameron House.

One of the attractions of “queer” rather then gay is that the word can move across and in-between genders. I support this fluidity, yet I am sometimes put off by “queer” being used as oppositional to “gay.” Sometimes I get a sense that certain people may be celebrated as queer, while others are dismissed as merely gay, whether personally, or in terms of their work. For example, if queer refers to polymorphous and performative role-playing, then AIDS lies outside of this terrain. AIDS is not exactly wonderfully perverse, it is wretched. And AIDS is certainly not strictly a gay (male) concern, but it was gay men who identified the epidemic, and who continue to be prominent in dealing with AIDS as a manageable syndrome of illnesses, rather than an automatic death sentence. Sometimes I hear “queer” rather than “gay” as an age differentiation, or an ageist dismissal. I know a local, female bisexual filmmaker who says that “queer” is synonymous with “bisexual,” which implies that strictly same-sexers are only gay. I personally find this attitude homophobic.

Queerness and the artistic? Well, “artistic” has, in the past, been one of those code words. Your uncle is “artistic” (and also a confirmed bachelor). Are we equating queer and artistic with being beyond bean-counter accountability, and ultimately beyond labels? Is “queer” a beyond-label that has, of course, become a label? Are both “queer” and “artistic” excuses for being beyond morality, or ethics? Wilde once stated that there is only good art and bad art, but I’m inclined to read Wilde’s surface apolitical snobbery as a defiance of class strictures regarding who should have access to beauty and leisure and everything else that is gloriously useless. Like art. But… here’s my traditional lefty Puritanism raising its head. I generally have difficulties with aestheticism and the belief that the artistic trumps everything, or that gifted individuals can do whatever they want at the expense of others. Egalitarian politics has never fit comfortably with either aestheticism or queerness. Class is a terrain that I feel is often neglected or dismissed in cultural and queer circles. Not everybody can afford to be fabulous, although (back to Wilde, that queer Irish socialist) one needn’t be nobility or royalty if one has a great eye and knows where the good thrift shops are.In Grammar & Not-Grammar by Gary Kibbins (2006), a book I edited, Steve Reinke interviews Kibbins, and they discuss parallels between artists and children. Reinke observes that all the images of the artist that Kibbins presents share one quality: the artist is never completely integrated into the adult social world. Steve makes clear that he doesn’t believe this, but certainly some artists perpetuate mythologies of the willingly irresponsible artist. So do divas of all stripes and persuasions. But I don’t think extended infantilism is particularly queer. Self-acknowledged queerness involves at least some degree of sociality, unless one’s erotic stimulus is the closet itself.

When I think of the 1940s to 1960s in New York artistic circles (Warhol is an obvious exception, and there are, of course, others. Jack Smith, if we‘re including film) I think of hyper-masculinity, and of course abstraction. Abstraction was belligerently modernist, while pop superceded abstraction, engaged with popular culture, and at least verged on post-modernism. In Toronto, in the late seventies, parallel to New York in the earlier period, there were either tensions, or else simply separate existences, for modernists and post-modernists. General Idea, Campbell, Buchan, and others liked to dance. They liked to mix up high and lower cultures. It seemed there was a dichotomy between pomo/homo/queer, and modernist straight. But if we’re looking to go beyond labels…

Mike: I’d like to ask you about dating experimental novelist Kathy Acker. Known for her aggressive prose liftings and theory porn novels, I was surprised to learn that one of her earliest amours was P. Adams Sitney who introduced her to what was then named Underground Film. Perhaps these small scenes did not require the strict segregation they have pursued in the meantime. Did this liaison spark literary ambitions of your own?

Andrew: I’m not sure there’s one big significant detail regarding Kathy Acker… I mean, my involvement with her was nearly 30 years ago. After talking with her and reading her novels of the period like The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula and The Adult Life of Toulouse Lautrec, I did pick up something about writing being as much about editing and/or collage as about actual writing. Kathy Goes to Haiti, which she described as an exploitation knock-off, influenced me by setting up genre fiction which was then interrupted or collaged with seemingly disparate elements. This strategy is not unlike Godard‘s mid-to-late sixties films, where a melodrama or noir thriller would be superseded by documentary elements. Cutting between analysis and autobiography was influential to many people. Acker could maintain elements of her own life while problematizing ideas of any fixed self or singular identity. Later on, it was easy to correlate elements of her writing with 80s artists like Sherrie Levine, who were quite candidly plagiarizing canonical works and declaring authorship. She claimed the works along with the artist‘s credit. Kathy was unique as an artist who shamelessly collaged and mixed disciplines which many felt belonged to different worlds: writing, visual arts, film, performance, and punk music. When I knew her the No-New-York, post-punk scene was becoming pretty high-profile, particularly The Contortions, DNA, Mars, Lydia Lunch. Kathy knew these people, but then she had her literary scene, which she felt pretty ambivalent about, but also very committed to.

I hadn’t been in touch with her for years when I was informed of her death, which depressed the hell out of me. The artist Susan Kealey phoned me so that I wouldn’t be freaking at the morning paper. A year before she died Kathy had come to Toronto as part of the International Writer’s Festival. I was supposed to meet her at LIFT, along with people like Louise Bak and Eldon Garnet and Kika Thorne, who shot her interview with Kathy the same night. The recording light was on at LIFT, so I didn’t barge in and interrupt. That was in the mid-90s, and because I was rather Luddite and not online, I was out of a lot of the loops, and didn’t know about her cancer. I wish I had maintained contact and friendship and dialogue, but there we go.

But I do remember our intense discussions and banterings. We used to argue over Beckett and Robbe-Grillet. I was pro and she was con. Kathy was, of course, really into Burroughs, someone Beckett once dismissed as being an editor not a writer. Hmm. She didn’t like a lot of the au courant German writers and film-directors; it was all their guilt and not hers. I remember going to see Herzog’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser with Kathy and she strongly disliked it. The next day we went to see Walter Hills’ 1979 cult movie The Warriors, and she loved it so much we snuck in for a second screening. She was writing a book called Girl Gangs Take Over The World at that time so there was a connection.

In the fall of 1979, I was in New York with The Government, and there were lulls between gigs. Money was tight, and I was fortunate to be able to stay with friends and read. I remember being quite taken by Susan Sontag’s I, Etcetera. The point-by-point writing ensured that she could skip plots and use a diary form while keeping up a formal symmetry. This blending of fiction and documentary really excited me. From late 1979 into 1980 I kept a diary, and flirted with the idea of mixing barely disguised social comings-and-goings with other observations. Some of these writings appeared in Impulse Magazine which started in 1979. Eldon Garnet was the editor and publisher, and he was very encouraging. I also wrote for General Idea’s File and for Fuse Magazine. I was rather shameless about working for different publications which didn’t always hold a high regard for each other. There were parallels and differences between the lyrics I was writing for The Government and these pieces of what Jeanne Randolph (a writer and critic I seriously admire) calls ficto-criticism. Meanwhile, The Government was rising and then falling, and many new tunes were instrumentals. Some people blend music and words very well, but I was never very good at that. I think it has a lot to do with the fact that I consider emotion to be non-verbal. Many gorgeous musics are mercifully spared the embarrassment of words attempting to represent emotions already there. Also, I love aural wallpaper, and words too frequently suggest meaning. All too obvious meaning.

I think the main reason I let The Government slide was the fact that I’d begun to consider myself more of a prose writer than a verse writer. And I was also interested in film. My novel The Disposables (1986) began as a film-script which loosely borrowed plot elements from different sources, but primarily Antonioni’s The Passenger, which was based on the idea of finding someone dead and then assuming their identity. The Picture of Dorian Gray, pulp fiction and Raymond Chandler were also filters. The main character is a decomposing pop star named Richard Monitor who is a David Bowie-type figure. I had projected onto Bowie’s Berlin period, particularly Low, which in its time violated many of the rules of the pop music world. It seemed to signal a withdrawal.

Another influence on the book was a videotape I made at The Western Front in Vancouver called Basic Motel (22 minutes 1980). I played an errant pop star hiding out in an anonymous hotel who is recognized by a room service woman. That episode was inserted into the novel. So there’s already a repeat pattern here oscillating between popular culture and hermetic modernism, or between anonymity and public personas.

I realize now that The Disposables overlapped with a performance piece I did called The Strange Case of Norman Desmond, which was also about a decomposing pop star. I adapted this performance for video in Immortality (27 minutes 1987). It featured many witnesses testifying about the iconic Norman; contradicting each other, as well as themselves. Many thought Immortality was an adaptation of The Disposables. It is true that I was working within a rather narrow set of references. Immortality is either completely unwatchable, or else so obsessive that it transcends self-conscious camp. I’ll let completists be the judge.

On the Labour Day weekend of 1983, I entered the Three Day Novel Writing Contest and rejigged my script-in-progress into a pulp novel. I used cheap uppers and all of that. Of course, I didn’t win the prize, but I decided to keep tweaking, trying to write a good novelette rather than a three-day quickie. I was thinking Cornell Wollrich filtered through Robbe-Grillet. I liked to milk the fact that so many French intellectuals were keen on American noir, for instance, Camus allegedly based The Outsider on James M. Cain. I think the slippage between fiction and documentary made American pulp novelists appealing, the characters were so thin, the lines between fiction and autobiography blurred.

During this time I was rather at sea. The Government was kaput, and I still thought about making records, if not live music. I made a couple of videotapes which I’m not crazy about. I’d been reading quite a bit of Screen theory about melodrama and its redemptive possibilities, and also Laura Mulvey, and I wanted to make videos from melodramatic stories or situations. I really wanted to make films, but that would have required a much bigger scale of operations. In the meantime, I kept working on The Disposables. I had done a small reading at Theatre Passe Muraille in the winter, and as a tag to Six Days of Censorship, Christina Ritchie asked me to read at Art Metropole in May of 1985. A.A. Bronson (one of General Idea’s three members, who collectively ran Art Metropole) asked me to publish it. Mixing up pulp with correspondence art and visual art, that was the idea. The Disposables was published in December 1986 and launched the following month, and it was all a bit of a whirlwind. There was a lot of activity, but it all happened in a vacuum. I thought The Disposables was like an airport book, one buys it for a quick read but the deeper questions leave a sour taste. It’s not disposable after all. Needless to say, this wasn’t the likely demographic of Art Metropole’s distribution system.

From 1996-98 I spent a lot of time working on an unpublished novel called Systems and Corridors. It’s sort of a murder investigation or mystery (the default plot), but it’s also socio-political. It concerns the strange relationship between a riot grrl type who resumes her post-secondary education and her Lit Crit professor. His name is Barry Ferguson, and he’s an academic star. I made him a weird cross between Camille Paglia and Pierre Trudeau—post-nationalist and post-identity politics. Too aggressively post-everything for his own good. Underneath it all, of course, Barry’s rather traditional. He’s into trade and that seems to explain his being murdered. But of course, that’s the too-easy scenario, so it goes on. The captivated, bisexual riot grrl becomes someone like Nancy Drew crossed with Jodie Foster. Systems and Corridors is a big sprawling mess but maybe a ruthless editor could wrench something out of it, I don’t know.

In early 2003, Pleasure Dome asked me what I was working on, and I told them that I had yet to complete a videotape called Mono Logical, which was originally intended to be seven self-performed monologues. I sat on that project as I realized it needed more than just a live speaker. Then I hit on the idea of mixing the monologues with a collage of some of my earlier works or shooting new super-8 films as backdrops.

Two of the initial monologues in Mono Logical were not conventional voice-overs. One consisted of three, 26-word poems. (I eventually wrote seven alphabetical poems, all of which run from A to Z. These seven poems are now part of a recent video called 12 x 26 (6:20, 2008). The seven poems are read over five 26-frame sequences of 26 images, plus a sequential 12-tone soundtrack, beginning with A and ending with G#.)

Another monologue was intended to be a “free jazz” fake saxophone solo. It was a comment on the vocal quality of expressionist music, and the fact that some emotions are best expressed non-verbally. I’ve always thought religious musicians had their templates: Coltrane and Bach. I get bugged by people about not playing music anymore and I think, “Maybe I should wear all white and go religious and play jazz. Ha ha.” In the first couple of Mono Logical performances, I improvised on guitar over a backing track, performing with my back to the audience a la Miles Davis, one of the ur-modernists of all time. It was intended as a thumb to those still waiting for a Government reunion.

The monologues in Mono Logical contradict each other and even themselves. There is the Internet professor who thinks public lectures are obsolete; then there is the student who enjoys potentially random events that can happen in public environments—that character is a budding walking philosopher methinks. There’s the Green Light Kid who can’t drive. And then there’s the town crier or priest, who simultaneously condemns and forgives. I was thinking Johnny Rotten as a priest, which actually he is, come to think of it.

Both dialogue and the performative monologue appeal to me because I am not the world’s most decisive person. I’ll stake out a position and then see the flaws in it. I would either make a terrible politician or a typical one. Self-performance of dialogue admits that the contradictory positions are the writer’s own, even though they are not the writer’s actual stances. There has of course been a tradition of the personal being political, though I would counter that far too often the personal is just the personal. But I am attracted to that uncomfortable zone in which a represented event hovers between invention and documentary. Or that something which might appear like shtick is actually serious.

Mike: Can you talk about the genesis of The Walking Philosopher (3:30 minutes 2001)?

Andrew: The Walking Philosopher was conceived and then shot in 1999. I had applied to the Toronto Arts Council with an idea for a super-8 film called The Trouble with Oscar Wilde, which proposed using voice-over segments against locations like The Granite Club, The Yacht Club, as well as sections of Rosedale, and the Church-Wellesley Gay Village. I wanted to touch on class inequities in and out of “the gay “community”.” I wanted to riff about tensions between being fabulous and functional. The voice-overs were not intended to be literally tied to the filmed neighbourhoods, but text and image were intended as formal compliments that would strike up further associations.

My application was probably too vague, so it was rejected. But I found myself accepting an invitation from Splice This! (Toronto’s Super-8 festival) to make a film on the theme of “Flawed.” I wrote a monologue about thinking as a moving bodily act—a form of cruising, in different senses of that verb. I think academics are sexy, and not only when they shut up. This monologue came to me quite readily and it was called The Walking Philosopher. I made a list of locations which included Philosopher’s Walk, Convocation Hall, the Water Works out in the Beaches, the CN Tower, and the entertainment district where there was actually a bar called Money. That’s what is flawed about the walking philosopher. He is not wealthy, or even comfortable, and thus must think about money, because he does, after all, live in a material world. Then I had to make the film, but I was in luck. James MacSwain, who had been my lover and who remains a dear friend, was attending the 1999 Images festival, and he was staying with me. I told him he could stay on the condition that he brought his Super-8 camera, and he came through. We went out and shot one glorious spring morning. I had intended to make in-camera edits, but we kept accumulating more shots and set-ups so that proved impossible. It was becoming a movie.

The Walking Philosopher was a departure from my earlier work, and not only in material terms. I was behind the camera shooting, and that creates the movement in the film. James had a roll of indoor film, so I decided to shoot a film-noir interlude in the basement of the 401 Richmond building that I wound up incorporating. Milada Kovacova edited it all together for me. I am nervous with splices and sharp objects, and she is a good editor and a generous friend. I showed The Walking Philosopher at Splice This!, with the audio on cassette, and it went over well. In early 2001, I transferred the film to video, incorporating the voice-over and music. This film has seen some action. Inside Out programmed it and referred to it as a tour of Toronto’s cruising sites. Well, yes, but I think much more. The Walking Philosopher references exchange systems—sexual, financial, intellectual. I know it played at Montreal’s Festival du Nouveau Cinema in-between Joe Gibbons and Donigan Cumming. Weighty company, perhaps it was a four and a half minute pee break?

Between 1999 and 2007 much of my work was made in response to residencies and calls for submissions. In each of those six years I made a super-8 film for Splice This! which had an annual theme and an invitational screening. I can’t remember what their subject was in 2002, but it reactivated The Trouble with Oscar Wilde musings, which led to The Headmaster’s Ritual (title courtesy of The Smiths). This was conceived and executed as a small shoot on the grounds of The Royal St. George’s College, where I had attended high school. When I was a teenager there, it wasn’t royal, but there were some rich kids who considered themselves royalty.

I made The Headmaster’s Ritual (3:30 minutes 2002) in spring 2002, when the assassination of rightist Dutch politician Pim Fortuyn was very much in the news. The assassin turned out to be a militant animal-rights activist, not a fanatical homophobe, let alone an Islamic jihadist. I found myself thinking about right-wing gay men—libertarians who equate sexual freedom and market freedom, but also flamboyant fascists. This train of thought led me back to that school with its right-wing Head Prefect who always played Margaret Rutherford in the drama-club and the Colonel Bogey headmaster. I hit on the idea of using a xerox of Hitchcock to represent the old headmaster, and one of Wilde for the new headmaster who encouraged students to have fun. I‘d heard rumours about Hitchcock getting off on public hangings, so there we go. The film itself is like moving documentary photography, but it does have a hard-line monologue, which I guess is why some programmers liked this piece. Between 1999 and 2005 I was relying a lot on voice-over or monologues. These performed narrations put ideas into play without adhering to them. This is an extension of my interest in portrait-performance, which is neither acting nor non-acting. But I had also decided to remove my face and body from the picture, for the most part anyway.

Mike: In Controlled Environments (33 minutes 1994) you play a pair of twin arts council bureaucrats caught in a series of seven conversations about the relation between artists and their audiences, the proposition that anarchy is the ultimate capitalism, propaganda versus art, and more. These split-screened talk backs offer an image of an arts “community” embroiled in itself, not only the video camera as digital mirror, but locked in a self-regarding embrace. Could you talk about how this project was developed?

Andrew: Controlled Environments consists of seven split-frame conversations between arts bureaucrats A and B (echoing Warhol), both portrayed by myself with minimal dramatic or costume variation. A is a resigned lifer or career-bureaucrat, while B is on the verge of quitting. B keeps challenging A about falling back into bureaucratic comfort zones. It is B who posits that only public art matters because it is at least visible outside art-world parameters.

This piece was written as a result of my own self-conversations regarding state-patronage and statism in general. However, those self-dialogues are themselves based on, and even appropriated from, dialogues with people both inside and outside of state-patronage systems. Probably because I might be considered a reformed entertainer, and also because of my lengthy history of service-sector employment as a waiter, I know more people hostile to state-patronage than many other artists. I know people who believe in the market as the great leveller, and people who distrust state-apparatuses as being hegemonic and elitist. I’ve known people who make overtly “political” art who choose to stay outside of the granting systems because those systems are, at least on the surface, apolitical and/or meritocratic.

I don’t think the two bureaucrats in Controlled Environments are indicative of a self-contained “art “community”.” I think these are two individuals who know where their bread is buttered, but who are also aware that their safety nets are tenuous and quite likely to collapse. One must remember that these two characters are chatting and arguing during their off-hours, except that they don’t really seem to have lives outside of their jobs. They are attached to each other, so to speak. One worries that the other has picked up the new boy on the job. One worries that the other drank too much at a Christmas party and made a fool of himself. They are both concerned that their jobs will become redundant, and along with them, the many artists who live and work outside of “the market.”

If I portray both A and B, then my perspective might well be neither or both. A viewer will hopefully formulate their own ideas. I usually prefer to problematize communicative models, presenting motifs that active viewers can take up and play with.

Okay, the self-embrace question. The mirror question. In the early days of the video medium there was not only the sensation of instant playback, but the pleasure of self-observation. I’ve never really enjoyed directly addressing audiences, I prefer my body to be electronically mediated. I’m not terribly keen on live entertainment, I prefer “cooler” viewing and listening options.

Do I feel that my work is condemned to the same old art networks? Sometimes I do. I’m not terribly well-connected anywhere else. But there have been exceptions. It meant a lot to me when my regular grocers saw Controlled Environments on YYZ-TV back in 1994. There was a Rogers Cable option available to time-based artists showing at YYZ Gallery back then. I don’t think I’m necessarily preaching to the converted, in fact, I don’t think I’m preaching. Perhaps in a couple of older works that misfired, but not in recent work. Something like AIDS Has Not Left the Building was admittedly originally made for a context (Pride Video) in which I thought the subject of AIDS had to be moved from the back burner to the front table, but I don’t think this tape is preachy. It posits a situation and then the ball is in the viewer’s court. That piece was intended for public venues rather then galleries, although it has played in both.

Mike: You mentioned once, in a late night whisper, that you are newly concerned with mortality. Perhaps you see your video work as a trace of the comet’s trail, a legacy even, your growing body of work at once pronouncement and record. In the past few years your parents have died, can you talk about how that changed the way you think about your own death (or did it?)? What would you like to say to those who will come after you? If you got to choose, how would you like to be remembered?

Andrew: For many people, I am more of a figure from an earlier era than a person living and working now. That often causes me to feel like the clock is ticking, and that there may well be contradictory obituaries at the end of the line. David McLean, one of the performers in Immortality, once told me that tape was like every obligatory AIDS memorial he’d ever attended, with its host of witnesses offering contradictory testimony. Who owns the narrative? Do I? No, one doesn’t own one’s narrative. But who hasn’t thought of eavesdropping on surviving friends (or enemies) as they talk about you after you’re gone?

My fascination with abstraction is another instance of death drives. Abstraction is all about molecular decomposition. The breakdown of everything figurative can be viewed as a decaying process, surely? Perhaps that’s why I resurrect the body now and again. I just shot a film for the upcoming Eight Festival, where I run toward a trophy and caress it. The film is called Trophy Life (3 minutes 2009), which is not the same as a charmed life although it could be. Much of my work progresses toward a void. I’m sure it’s my parallel needs for the ultimate physicality and to move on to another world.

There’s a connection here with my flicker film fascination. The single-frame editing rhythm is akin to what I experience when I think I’m going to fall asleep, or into a temporary death. I’ve tried to capture that very moment of losing consciousness when I’ve had a hard time falling asleep (which is not infrequently); and of course this doesn’t work because I’m too self-conscious about experiencing that exact fabulous moment. I have been around people in the final stages of their lives, when they oscillate rapidly from here to there. My parents are both gone, and way too many of my friends died too young and too early. I’m currently in a holding pattern — an extended “what next” moment — and I wonder if there is a “next.”

I’d prefer to be remembered by my work, as my life really isn’t that unusual. I’ve done quite a few things that I’ve enjoyed doing, although it’s not as if I have all that much to show for it. I do see some continuity throughout my interdisciplinary career. Some of the formalism of my later videos is not unprecedented. In some of the early Government songs, I would take a faulty Xerox and then attempt to write music in the shape of that accidental image. I’ve always been interested in grids that decompose, many kinds of freedom become possible only within strict boundaries. I love Laura Marks’ blurb, “Freedom is paralysing, grammar is liberating.” My flicker fetish comes out of this mindset; being presented with a limited set of choices is exhilarating. Choices have to be made, otherwise, why not just drift away and enter into Chanceville? Why not set up an image-generating apparatus and press sample-hold? That can be as good as the images and the sounds are, but I prefer chance interludes to be situated in the context of rigorously formal structures. So, maybe that makes me a modernist who doesn’t entirely believe in the death of the author. Maybe that’s been a tall part of my life story, and maybe that’s what becomes apparent in my body of work. The rest is just biography, and that holds limited interest.