Power Plant Gallery exhibition:

Peter Campus, Joachim Koester, Ryan Trecartin, Sharon Lockhart

Toronto, April 2, 2010

Peter Campus

Let me begin with a fantasy, my oldest dream. That it would be possible to make movies that would not only be smart and beautiful, but useful. You would laugh and cry and laugh again, and when it was over you would eat the video. Or unspool the tape, and use it as bandages, or a tow rope to pull cars out of a ditch, or as a ribbon you would wrap around a child’s present. We are all familiar, I think, with video as a presentation model, with video as a frame that presents moments of a world, with video that takes time. But what if video could be used in the other direction, as a tool, as a tool to grant us time. And what might be more useful for us now, now at this time, when we have no time. When some of us at least are suffering not from an attention deficit disorder, but a time deficit disorder. Could there be a video that would grant us the gift of this time that we seem to be always running out of? The time that we have disappeared because of the time bomb that we have thrown our arms around, I’m speaking of course, about the home computer. The computer operates as a kind of black hole of time, it is a machine designed to make time disappear. Could we build some kind of video machine that might soothe our interface? Our irresistible, already seduced, digital compulsion.

What if the next time you got really angry, or really upset with someone, instead of letting all those ugly words climb out of your mouth, what if everything in the world stopped? What if, exactly at this moment when you can feel your temperature rising – you’re getting hot, you’re about to make the worst decision of your life – you get this gift of time. It doesn’t need to be very much time, maybe there’s a small delay, maybe there’s a few seconds of delay. Those few seconds, aren’t they an invitation to change everything? I mean to invent yourself, to stop repeating, to work yourself out of the groove, the things you can’t help saying or can’t help wanting, or can’t help doing again and again, as if they were you. As if they were yourself. What if we could make a video that could help with the creative project you name as yourself?

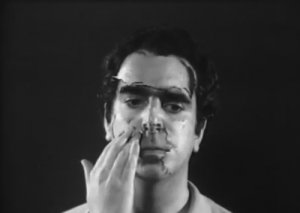

Joachim Koester

Before there was video there was film. The machines of film. You can see the film here as an object, it is both an object, a thing you can hold in your hands, or run through a projector, and a flickering image on a wall. It is a thing, and a process. When we say “film”, I’m going to see a film, usually we are referring to the thing that appears on the wall, and not this, this ribbon of plastic with punched holes in its side, offering us truth, or at least the illusion of movement, 24 times per second. When we look at a strip of film, we can see that it’s made of still pictures, small photographs, and that each photograph is separated from the next by a small bar of darkness. If our eyes were quick enough, if our seeing was good enough, we would see this darkness between the photographs. Instead of the illusion of this continuity of movement, this trick of the machine.

This installation might have something to do with the space between what appears to be moving, but what is actually still. It might have something to do with the darkness that separates each of these pictures, that separates each of our pictures. It’s a kind of reminder, isn’t it, that the impact, the force, the impression, that pictures make, might reside not in the place where words are formed, but in the unconscious. By which I mean, in the body. The body of film, the body of the material, the bodies of the subject of the film, the bodies of the viewers. The space in which you’re invited to move around, as a body, as a body amongst the bodies of film.

What are these bodies doing? Could this be an act of drawing? Drawing in motion? If you concentrate on a single instant, a single line, you can watch it move through a series of variations, or you can zoom out with your looking, and take in the entire field, where all of these lines form abstract figures in restlessly shifting gestalts.

In the middle screen, the figure arrives, or does it? Each of these people look like they are trying to make a beginning. Starting from scratch, starting over, starting again. This is the starting line, only it’s not a race, and nobody finishes. How do I stand here, here in this place, in this place next to the place that you’re standing in. How do we stand together? You and I, strangers, friends, familiars. How can I touch you so that it’s slow enough to feel it, how can I find the right speed, the right intensity, how can I be here now, now, now, without dragging all of my stories into the room, all of my favourite tunes that I like to play over and over again, the tunes which tell me, which replay for me the story of myself, and which keep me from ever seeing you, from ever really being in the same room as you are.

How do I stand? And how are you standing? What and where is our standing?

And then there is a third screen, filled with bodies and a restless, convulsive movement. They remind me of an old church gathering. They remind me of bodies caught in the grip of some possession, bodies that are not “themselves,” that don’t belong to “themselves,” that are moving according to some other, external order. Possessed. I wonder if these bodies might also be a reflection on dance and dancers? I wonder if dancers are sometimes thought of as empty canvasses waiting to be filled, to be painted, by the choreographer. The mind and the body. The mind of the choreographer, the body of the dancer. How can I become again a body, how can I return to the deepest understanding I have? Is it like this, is this necessary, to submit to some external force, some trial? Do I have to surrender, to lose myself, before finding myself? To find myself, so that I could come here, to the second screen, and begin again, having already experienced myself as something other, something alien, to have broadened my perspective, to feel more, and hence to feel your feelings more, and hence to be able to feel our standing, our relation, the space between us, the small moment of time between us, more deeply.

Ryan Trecartin

When I came to check out the show I arrived with two other people, one entered this space, this interlocking maze of seven rooms, seven videos, seven parts. And I never saw her again. I don’t really know what to say about Ryan Trecartin. This makes me feel better than perhaps it should. I mean, this not knowing. How I long to know, to give it a name, to attach a story to it, to roll it all up in my hands like a little ball. To grasp it, and exert mastery. To name, to grasp, to know. But I don’t now what to say about Ryan Trecartin. Other people say things like he was born in 1981 in Texas. He went to art school in Provincetown, which is close to New York, but is not New York, and graduated in 2004. He came out of art school six years ago, he’s not yet thirty years old.

Each of these seven rooms and seven movies tells a story, a very particular story, with characters, but he’s faster than a speeding bullet, so while I try to follow, I keep tripping up. One of the stories, in one of the earliest video tapes, begins with a very pregnant mother doing yoga. Her name is Carryon Ova. She seems to be speaking to her unborn children, the quadruplets, the four who are waiting to come out. But maybe she’s not. She certainly talks a lot about dying, she’s going to be killed by her husband, she predicts her own death, though time, identity, birth and death, it’s all up in the mixmaster. It’s all being blended together. And the story? The father doesn’t want four kids, he wants three, so in an effort to, you know, get along, to help the family get along, two of the quads merge into one. I guess that’s what they would write, if this wound up on late night television. Mom dies, four kids become three. Five stars.

Frederic Jameson wrote a keynote essay on the postmodern condition, not a picture, not an art practice, but a condition, a kind of world. In order to understand this new world he offered up two pictures: the first, imagine it if you may, is that the postmodern is like… a pair of dark sunglasses. Bent around its frame, the world now appears as a picture, and it’s all there on the surface. Sunglasses take all those horizons, and the hopes of those horizons, and lay them out across a single surface. In the world of the postmodern, in the postmodern condition, you really can tell a book by its cover. The second picture he offers is a flatbed truck. What can you put on a flatbed truck? Well, pretty much anything. You throw what comes to hand onto the truck, you heap it on, you toss in some of your favourites, and some other things that you can’t even name yet. It’s a casual collision, it’s new neighbours, new combinations. The sunglasses, and the flatbed truck, and the videos of Ryan Trecartin.

It’s a queer, queer world Martha. Bad wigs, bad make up, bad paintings, cheap video, thrift store chic, Ikea set dressings, friends as actors: you use whatever you can find. It’s cheap and disposable, like me, like you. There is no ground here, and the fiction of the self, of me, of my world, of my wants and not-wants, is projected here as a series of temporary positions, always staged for the camera eye of course. The self is no longer imagined on a movie screen, but as the screen of our computers, the desktop screen with all those applications open all at once. The self is part word document and part picture, all in glowing candy colours, all open at the same time. Once the self is emptied out, it’s delivered to the computer and reprojected as a series of avatars, of presentation models done up on the spot, improvised in a multitude of posings and postings, sprayed across the surface, the surface of those sunglasses, the surface of the desktop computer, in a hyperbolic demonstration. Not the self as a multi-tasker, but the self as multi-task. All at once. Ryan can talk faster, think faster, videotape faster, change faster than the daytime television stars that he is busy emulating. The flatbed truck of these selves have been made out of Oprah reruns and Lady Gaga outtakes and most of all Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures. Everyone can be renamed, backgrounds can’t be entered until they are rendered, and traumas are short circuited and dished in hipsterism fortune cookies like: “I was raped by my dad’s career. I’m an asshole.” Or: “I’m finally just an “as if.” Or: “I just developed a new personality for the living room.”

Or how about his, from the mouth of one of the quadruplets. After the double masectomy, he/she presents as an intersexed homocore, musing on the disasters of a mother’s death, and a father’s restless dissatisfaction: “Being abandoned (she/he says) is like wearing a sexy necklace. You’re free to take it off. Being post-family and pre-hotel is over.” Or is it? I invite you to see for yourself, to inhabit a place that is post-family and pre-hotel. There are hours of video on display, the earliest works in this exhibition are still available, along with a vast amount of earlier Ryan fabulations, on his Youtube channel.

We’re going to take ten minutes here, which might feel like the shortest ten minutes of your life, or the longest, and then we’ll meet outside the fourth and final room that belongs to Sharon Lockhart.

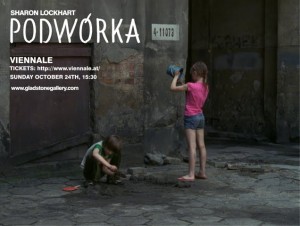

Sharon Lockhart

This is your task, your mission statement. It comes in a small envelope with a plane ticket and a passport and a 16mm camera. The message of course self destructs after you read it. This is what it says: Your mission, should you accept it, is to go to a country you’ve never been to, you’re going to go to Poland, and you’ll have many experiences there. You’ll meet many people there who are going to be important to you for a long time. Why? Because you’re going to arrive with your eyes open, with your heart open, and your task is to make a movie about this country, yes, the whole country. Oh and there’s a prohibition, a stricture, a rule, there can’t be any talking in your movie, or at least, you can’t sit someone down in front of your beautiful perfect camera, which only shoots when the light is good, you can’t get anyone to sit down and talk to you, and tell you about this country. Or tell you what it means to have a body, to live inside a body, in this country. In the very special way that they do.

You decide that instead of trying to cram everything into your movie, you’re going to look at a few things, and you’re going to look at them as deeply as you can. This means of course, that you’re going to give them time, it takes time for another country, another picture, another person to appear, and when you come back, you’re going to offer this time as a gift to all of your viewers.

Each scene, each moment of looking, is separated by darkness. Like the darkness of each frame. Like the delay, the delay of time, in the Peter Campus video. Think of it as a blink, a refresher, a pause. So that the work of looking might begin again.

I’d like to conclude by telling you an old story. It was a story first told 2500 years ago. And here’s the really unusual thing about this story, the nearly uncanny thing about this story, is that if you listen to it really closely, it’s almost certainly a story about you. It goes like this.

There’s someone walking, oh yes, even in the twilight, you can see they look familiar, don’t they, they are moving in that familiar way that you know so well, and they’re on a kind of path, they’re walking not on a road, not on anything paved or ploughed, but they’re on a kind of path, and you’re walking walking, and then you’re forced to stop. Why? Because you are confronted with a small body of water. The shore of this little bay, is filled with glass, and sharp small stones, which cut into your shoes as you walk around here. But as you look across the bay you can see, not that far away, a body of land, and it’s green, and there’s people over there, and they look fine and friendly. So this is the question: how the hell are you going to get over there? You didn’t pack your ultra-deluxe inflatable raft, sorry, it seems you’ve left that at home, again. So you start looking around, you start looking around your own life, and you gather whatever you can, whatever there is, whatever happens to be around, to make this raft. The only important question is: will it float? You don’t bother with oars, making a sail is beyond you, you lash together some already fallen sticks, some timbers, you float your home brewed raft into the water and paddling with your hands and feet, you set off and reach the other place. Once you’re there, you have this decision to make: do you drag around your great invention, the raft you made out of bits and pieces? Well, it’s not going to be much use to you over there is it, now that you’re on land again, and it’s heavy and wet, so you decide to leave it in the water.

This story was told by the Buddha. He imagined that there would be a moment in everyone’s life which would be difficult, which might seem even impossible to get through. Perhaps it’s the death of a friend, or an ailing parent, or difficulties at work. And what he’s asking, I think, is that we act as a collage artist, working with invention and flexibility, you know, like these children, these children here in Poland, who are busy remaking these dismal post-industrial waste lands into arenas of play and happiness. Because the point is not to transcend this world and find a better place in some starry hereafter, but to know that heaven is here, in this place, in this place between you and me, where we can invent extra seconds for each other, if we want, where we might grant each other again the gift of time, and in that time we can come to some feeling of where we might stand, of our standing together, as we are busy inventing ourselves, this moment, every moment, now.

Peter Campus: Reflections and Inflections

Curated by Gregory Burke, Director of The Power Plant

26 March – 24 May, 2010

Beginning in the early 1970s, American artist Peter Campus has consistently explored the formal properties and possibilities of video. This critical engagement is visible in his 1973–76 series of performative exercises that includes the classic Three Transitions (1973), as well as in a body of work examining video’s relationship to the gallery space and the medium’s capacity for transforming viewers’ perceptions of self and of duration. In this exhibition, Campus stands as a key figure who laid the groundwork for many artists’ explorations of screen space.

‘Peter Campus: Reflections and Inflections’ juxtaposes the iconic early work Anamnesis (1974) with a new multi-channel video, Inflections: changes in light and colour around Ponquogue Bay (2009), spanning thirty-five years of Campus’s pioneering practice and his move from treating video as a sculptural to a pictorial medium. Anamnesis confronts viewers with a closed-circuit video feed of themselves; however, its three-second delay disorients one’s experience of time and embodiment. The British Film Institute-commissioned Inflections… fills six monitors with its hypnotic, slowed-down images of Ponquogue Bay, Long Island, digitally altered to create painterly abstract landscapes that hover between stillness and motion.

Peter Campus (born in New York, 1937) received a BS in experimental psychology from Ohio State University, Columbus, and graduated from the City College Film Institute, New York. In addition to participating in numerous biennials and major group exhibitions, Campus has had recent solo exhibitions at Kunsthalle Bremen (2004), Albion Gallery, London (2007), and the British Film Institute, London (2009–10).

Joachim Koester: Hypnagogia

26 March – 24 May 2010

Curated by Helena Reckitt, Senior Curator of Programs of The Power Plant

Dancers wearing everyday clothes convulse and gyrate, enacting symptoms of a spider’s bite in a riff on the Southern Italian dance called the tarantella; a man mimes actions that channel shamanic gestures; abstract squiggles evoke the experience of writing after consuming mescaline. Hypnagogia, the threshold between consciousness and sleep, is explored in the three films that comprise Joachim Koester’s first solo show in Canada: Tarantism (7 min., 2007), My Frontier is an Endless Wall of Points (after the mescaline drawings of Henri Michaux) (11 min., 2007) and To navigate, in a genuine way, in the unknown necessitates an attitude of daring, but not one of recklessness (movements generated from the Magical Passes of Carlos Castaneda) (3min, 2009). Projected onto floating screens, these black and white 16 mm film loops suggest conscious and unconscious states and gestures, irrationality, loss of control, possession, and the “fringes of the body” that Koester terms “the grey zone.”

Joachim Koester (born Copenhagen, 1962) is a Danish artist based in Copenhagen and Brooklyn. He represented Denmark in the 2005 Venice Biennale. Recent solo shows have taken place at Extra City, Antwerp and Overgaden, Copenhagen and group exhibitions include ‘Dance with Camera,’ ICA Philadelphia (2009), ‘Altermodern, Tate Triennial,’ (2009), ‘The Return of Religion and other Myths,’ BAK (2009). Koester is represented in New York by GreeneNaftali, in Copenhagen by Galleri Nicolai and in Brussels by Jan Mot.

Ryan Trecartin: Any Ever

26 March – 24 May, 2010

Curated by Helena Reckitt, Senior Curator of Programs, and Jon Davies, Assistant Curator of Public Programs of The Power Plant

‘Ryan Trecartin: Any Ever’ is the first Canadian solo exhibition by the American wünderkind, a sprawling seven-video suite amalgamating his ambitious new four-part series, Re’Search Wait’S as well as his acclaimed 2009 video triptych Trill-ogy Comp. Destabilizing and amazing his audiences, Trecartin’s hyperactive and collaborative performance and video art practice embraces a lo-fi aesthetic of chaotic excess to realize his heady explorations of consumer culture and fractured identity in the digital age. With an insomniac energy and frenetic editing, Trecartin choreographs a cracked parallel universe only slightly more surreal than the one we actually inhabit.

His most ambitious exhibition to date, Trecartin’s frenzied riffs on our increasingly virtual world in ‘Any Ever’ will be staged inside a network of “containers” in The Power Plant’s largest gallery.

Ryan Trecartin (born in Webster, Tex., 1981) was educated at the Rhode Island School of Design and is currently based in Philadelphia. He has had recent solo exhibitions at the Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus (2008), Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2008), and Kunsthalle Wien (2009), and was included in such group exhibitions as ‘USA Today’ at the Royal Academy of Arts, London (2006), and ‘The Generational: Younger than Jesus’ at the New Museum, New York (2009). In 2009, Trecartin won the inaugural Jack Wolgin International Competition in the Fine Arts, and was named Best New Artist of the Year in the First Annual Art Awards at the Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Sharon Lockhart: Podwórka

26 March – 24 May, 2010

Curated by Gregory Burke, Director of The Power Plant and Pablo de Ocampo, Artistic Director of the Images Festival

‘Podwórka’ captures six groups of neighbourhood youth as they play in seemingly deserted yards, offering an intimate portrait of daily life in Lód´z, Poland. Shot with a fixed camera, this single-channel video projection highlights American artist Sharon Lockhart’s concern for the interrelationship between the still and the moving image.

Evolving from past works for which Lockhart has entered into a community to document its inhabitants—such as Pine Flat (2006), the result of three years spent in a small town in the Sierra Nevada—Podwórka evidences the artist’s nuanced anthropological gaze as she represents both individual and collective identities. The work’s meditative pace and absence of defined narrative affords Lockhart’s subjects a sense of freedom that also extends to the viewers, who are encouraged to imagine stories for the children portrayed, beyond the space of the screen.

Sharon Lockhart (born in Norwood, Mass., 1964) received her MFA from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena and is currently based in Los Angeles. Her acclaimed film and photography work has been shown in galleries and cinemas around the world, including in ‘Life on Mars: The 55th Carnegie International,’ Pittsburgh (2008). Recent solo exhibitions have been organized by Secession, Vienna (2008), Kunstverein, Hamburg (2008) and Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2009).