We Have to Do It for Each Other: an interview with Allyson Mitchell by Kami Chisholm and Mike Hoolboom (Winter 2017)

Mike: 3 Minute Rock Star felt like a seismic event in the experimentalist queer margins, a one-night stand organized by Jane Farrow and yourself. Because the all-new work was requested (commissioned seems too stuffy a word), it drew borders around a self-identified community (however temporary and shape-shifting). The movies were short, fun, performative, personal, and often featured the artist. Is it too much to say that the night’s proceedings set up a template for some of your future makings, not to mention a brace of other other local luminaries?

Allyson: 3 Minute Rock Star was part of a fully tectonic shift in my life and it rode on the aftershocks of my Saturn return. The project began in the fall of 1995. I was 28 years old and had only been out as a dyke for a couple of years. I was living on Augusta Avenue in Kensington Market in Toronto. Jane and I had just become lovers and we were flying high on new love. We took a road trip to Florida in the winter and shot a bunch of super 8 film on the way. I had never shot super 8 (or anything else) before and was amazed how it looked after it was developed. We also took a road trip to Buffalo in the winter to see a documentary-in-progress by Lucy Thane called She’s Real: Worse Than Queer (51 minutes 1997) at Hallwalls. I began volunteering at Buddies in Bad Times in an attempt to connect with other gay people. When I was doing this I met Ian Jarvis who encouraged me to also volunteer at the Inside Out Film Festival where I could connect with folks interested in film and video. Everything was just clicking for me — not in a Church Street gay world kind of way, but in a more resistant queer art world kind of way. I was really in love with the idea of Riot Grrrl and the permission that it gave to make art without an art degree, knowledge of art history or any kind of aficionado credentials.

I had also participated in a DIY video-making project called “On the Fly,” run by Scott McLaren and Andrew Bee. They invited a group of us to make a video within a restrained amount of time with some editing support. For this project I took inspiration (with permission) to create a video using a poem that I had read in the Daily Xtra newspaper called My Very Own Afterschool Special by Megan Rivers Moore. It is about two girls breaking up in the high school cafeteria. It is sexy, sad and mad. I was into Ani DiFranco at the time and asked her for permission to use her music in the film and she gave it to me. Classic early 90s lez. These points of entry into filmmaking and queer communities set the stage for the 3 Minute Rockstar.

The idea for 3 Minute Rockstar probably came from Jane. She is a powerhouse at getting things done and organizing people. She had recently moved to Toronto from Vancouver. We had two super 8 cameras at our disposal. We talked with Margaret Wagner at Exclusive Film about supporting the project and I can’t remember the details exactly but Exclusive gave us a deal on the film development and a bulk order of super 8 film. We put a camera kit together that included an instructional sheet on the basics of using a super 8 camera, rolls of film, batteries for backup and a photocopy of a calendar for the months of September and October. We invited lots of folks to make a film. The parameters were that they had to be first time filmmakers. Jane was really connected in the queer and artist scenes and knew so many people. She was charming and bold as hell. The stipulation for joining was that the maker had to self identify as a freak in some way. I realize that this term is problematic and we were remiss to use it, but we were trying to land on something without defining it. We didn’t want to make it gay and not “straight,” we didn’t want it to be only about how you identified sexually. It was leaning towards the punk rock, outsider, misfit, weirdo, awkward, politicized identity of freak. It was the 90s and we weren’t as nuanced as we hope to be now.

Each participant had to give us $50 and that paid for the film, the developing and the screening. This covered costs and we weren’t looking to make a penny. Each person was limited to one roll of film and that restricted the available time, it meant people had to plan it out to some degree. The project hoped for a mix of spontaneity and economy. You’ve got three minutes — do your worst. It was also a democratic form. Everyone was given the same tool, the same amount of time to make and the same amount of time on screen. No matter how good or bad, it was only three minutes. The person who had the camera last was responsible to leapfrog the camera kit to the next person on the calendar. It was a bit wild but it worked out in the end. No one saw their film until the night of the actual screening where all the participants would come together and look at the work. We developed as we went along and would hold the film up to the light to see if there was an image and if something appeared in the first few frames we were good to go. A couple of films didn’t work and we were able to get the makers to reshoot. This worked as a built-in safety net for the folks who didn’t get it right the first time. Everyone got something on screen. Another restriction (or freedom) was sound. There was no synched audio. People were invited to do their sound live at the screening or provide their soundtrack on cassette cued up so that when the projectionist hit “play” so did the audio person.

The Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto (LIFT) supported us by helping to gang up the films and Roberto Ariganello did the sound and Marcos Arriaga did the tricky projection. We held the screening at the old Club 360 Legion on Queen Street West. The event was packed and the energy was intoxicating. Avi Lewis from The New Music interviewed us. The club ran out of beer. Everyone who made a film (50 in total) brought all of the people who participated in the film and their friends. It was a recipe for success. And a recipe I have gone back to time and time again. Jane and I went on to do other versions of 3 Minute Rockstar, one with youth at Regent Park Community Center and Inside Out. That spring the Images Festival, which was headed up by Deirdre Logue, cherry picked a “best of” program (not in the actual festival guide because it was pulled together after the actual printing) and that inspired future programs like Homebrew (1999) and projects like Art Fag (2000) and Art Dyke (2001). A small grant from The Lesbian Community Appeal paid for a transfer to video, and this package can be seen at CFMDC (Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre).

The recipe is about numbers of people collaborating and helping each other, sharing resources, and being open. The openness is the risk of failure, looking dumb, trying hard, being publicly sexual and hanging your ass out (and this happened literally in some of the films in which dildos appeared no less than five times). For 3 Minute Rockstar, Jane and I wanted to be as vulnerable as all the folks we were asking to make films, so we both made our own films as part of the project (though technically we had made the films before, but only like months earlier). I made a piece called Chow Down (3 minutes 1997) about a fat girl trying to pull together the perfect outfit but nothing really works and there is lots of wardrobe struggles along with a soundtrack mash-up of songs that contain food lyrics from the Beastie Boys, Jane Siberry, Princess Superstar and Cibo Matto. Somehow, emboldened by this music, the girl (me) finds the right tight pants, wig and push-up bra that give her newfound self-esteem. She takes this outrageous confidence down to the kitchen where she opens the fridge and is serenaded by a bunch of paper dolls lip-synching to Brick House by The Commodores. Chow Down was the first time I showed my body undressed. I was just finding my voice as a feminist/fat/queer person then.

Mike: You were part of a fat activist collective called Pretty Porky and Pissed Off that featured a winning blend of art and politics. You staged an anti-diet action at Ryerson University on March 4, 2004, along with Joanne Huffa, Abi Stone, Mariko Tamaki, Tracy Tidgwell and Zoe Whittall. This was documented in your film Free! Bake! Sale! (4:20 minutes, 2004). It’s a very local phenom, your group meets people at the door with a bevy of baked goods, and you seem content to speak to people one on one, as if politics were a question of turning one head at a time, or daring to start up a new conversation. Can you talk about why you started the group, what kinds of actions you undertook together, and how you were received?

Allyson: Pretty Porky and Pissed Off started in 1996, around the same time as all these other things were going on. I was an undergraduate Women’s Studies major at York University and I was excited to be learning about feminist theory and activism. Through mail order riot grrrl distribution via Mr Lady Records, I was lucky enough to get my hands on a copy of Nomy Lamm’s famous zine “I’m So Fucking Beautiful” (1993) — an analysis of the intersections of gender, ability, queerness and knowledges from other margins. This changed everything for me. In my life I had never heard one whiff of a notion that it was okay to be fat, queer or atypical in any way. I devoured it. I wanted to sit on it, put it inside me, blow it up and blow it out of me.

I met the artists Ruby Rowan from the band Queen Size Shag and writer Mariko Tamaki. These women and their networks of politicized people drew me in. Collectively, we decided to take this energy, love/rage and make it public and put it on the line with our bodies. We used song, fat camp aesthetics, and street theatre to practice what we were hoping to manifest as truth.

Every action began with a conversation. The first demo we did was to walk up to people and ask them, “Do you think I’m FAT?” as a way to provoke a response, usually a denial of the subjectivity that we had been slotted into our whole lives. We were often met with a laugh or an uncomfortable shrug that offered an opportunity to talk about the average sizes of women’s bodies in North America and the denial of our existence by people who make clothing. Literally, we wanted to dress our fat asses. It is also true that spectacle can do the job of turning heads. We used camp, sugary treats, and the offer of a dance; most people find some kind of delight in seeing a fat woman shake it in a performance of brazenness. We tactically leveraged humour to draw people towards us rather than having them turn away.

The first performance we did was at the slapped together community fundraiser to support the organizers of the Pussy Palace — the first women’s bathhouse that was raided by the police and used as a platform to humiliate and intimidate sexually empowered women. In the performance we danced to Henry Mancini’s Baby Elephant Walk and sat on cheap grocery store cakes in tight black leotards and wiped whipped cream from our asses and stuck sticky fingers in our mouths and the crowd went wild. This emboldened us. By 2004, when we staged and documented Free! Bake! Sale! we had been at the task for eight years. During that time we learned so much, we sharpened our language around fat politics, we met fat kin working the movement in other places in the UK and the US. We had spoken publicly, humped muffins at Vaseline, conducted workshops with middle school kids for the TDSB (Toronto District School Board) and created a collaborative life story performance called Big Judy.[1]

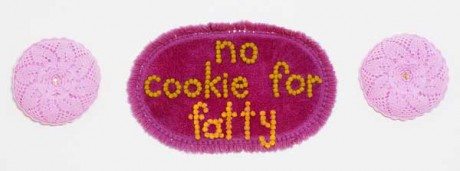

In 2004 at Ryerson University on No Diet Day we gave out cookies and Rice Krispie Squares and we also gave out apples. The Atkins diet was the rage at the time and on that diet apples were not allowed as they were labelled carbohydrates. What is more outrageous? A fat woman eating a cookie in public without shame? A group of fat women breaking through a wall of passive-aggressive politeness to invite you to join them in eating an apple? A bunch of queer fat dykes taking up space on the edges of the very site of the most acute public body policing — the college or high school cafeteria? As a collective of politicized fat women, it felt like the do over you only dream of — returning to those sites of trauma with the knowledge, experience and confidence gained through years of unlearning… with your fat girl gang backing you up!

We don’t have lots of documentation of the early PPPO’d demos and performances. In order to create Free! Bake! Sale! I had applied to make a video as part of a thematic residency at Trinity Square Video on the topic of “eat” in order to make a document of the action. Lukas Blakk and Tracy Tidgwell were also part of that residency at TSV and they made a wonderful piece about fat, class and comfort called Fallout Food (5:40 minutes 2004). The opportunity to work in the editing suites at TSV in order to meld the documentation with music and text allowed me to nuance some of the ideas and make them very very clear. Particularly the texts at the beginning and the end.

At times our work with PPPO’d veered more towards performance and further from direct action. We felt both methods were differently effective at getting a clear message across to make social change. Providing joy and thoughtful entertainment for an affirmed community of supporters rooting you on is one thing, but direct one-to-one conversations with the general population does something different. You can feel it in the moment. The lies behind the veneer of politeness can’t be as easily sustained during eye contact. People can’t look away from the fat body, the fat person who is connecting us across the loathing, hatred and fear. Both kinds of energy were necessary to sustain the project. One fed us and with the other we were the caterers.

A few versions of the history of PPO’d has been written in different places. I wrote my PhD dissertation[2] about what I have come to know about fat by interviewing fat subjects, but also through my experiences with performing fat resistance with PPPO’d. There is lots to say about these politics. What we were messaging in the 90s would be different today, there were so few visible fat bodies then. It feels like there are more now with social media, on television and film and there is more of a general understanding of (though it hasn’t necessarily alleviated) fat phobia. Our politics needed to move as they were appropriated by ad campaigns from places like the Body Shop and the Dove Campaign for Real Beauty. Our politics also needed to be complicated by new experiences and audiences. I think that generally people liked PPPO’d. We would hear thunderous applause in most places where we performed. Support and excitement were palpable.

Critiques around fat body politics and self-esteem as a white feminist issue were directed towards us by ourselves and others. The work we were doing existed largely pre-social media so there weren’t as many anonymous public outlets for people to weigh in. Audiences showed us love, at least to our faces. More critical response came from the media (Leah McLaren in particular) or when we were set in opposition to the director of an obesity centre. There were people who could not get past their ingrained ideas about fat, no matter what we said or how we demonstrated the opposite.

Of course the messaging of PPPO’d was not just to get people to be fat (which some simple detractors supposed) but to use food, sugar and our bodies in combination to show not only skin but bulges and vulnerable histories. We wanted to support each other, unlearn the out-of-proportion shame associated with our bodies and related to eating practices that are a huge part of how we know who we are and how we are supposed to be. Often we had felt that we simply shouldn’t exist in the first place. We fed each other and the visuality of food was important for us to play with in order to dismantle some of the power it held over us.

At the Ryerson demo we experienced all of these things. We flung ourselves into the world and offered a proposal, a way of being that defied how most fat women should be. Most people ignored us, some made fun of us, but a few stopped and talked to us. All of those people — whether they accepted our literature and conversations or not — had to literally face us. We just hung out near the giant student cafeteria. Even shy ones could watch us through their peripherals and now the video doc allows that conversation and gawking to continue.

Kami: Food, sweets, eating, and fat abound in your work. From Chow Down to Candy Kisses and more, your work eschews the disciplining of bodies in favor of excess, indulgence, performance, pleasure and play. In Candy Kisses sweets take on a life of their own and even become anthropomorphized. But food does not only take center stage in the works themselves. You detail above how food and fat politics are central not only to your film work, but how you combine these works with performance and the sharing and consumption of food. In this way food, eating, and fat are not just thematic or theoretical concerns, but also helps structure the creation of spaces, interactive engagement, care, and nourishment. These threads weave through all your work, from the films to performances to teaching, and are also the central concern of your PhD dissertation, “Corporeographies of Size: Fat Women in Urban Space” (2006). Can you describe what you mean by “corporeographies” and how it relates to your process as well as the works themselves?

Allyson: Corporeographies is a relatively obnoxious academic term first used by feminist geographer Vicky Kirby {Kirby, 1997 #2023}. Another theorist, Robyn Longhurst, fleshed out the idea by looking at how pregnant bodies in a public beauty contest in Australia interrupted notions of proper and improper gendered behaviour, their appearance questioned how there could ever be a definitive singular body {Longhurst, 2001 #2024}. The pregnant body has another body inside of it for one. And the actual protrusion of belly and breasts push against the body’s boundaries. Fat studies theorists have built on these notions to think about how fat bodies do something similar, they exceed boundaries. They may jiggle when they move and expand when they sit. These examples show how spaces are constructed by bodies, and that bodies are also spaces that can defy scale and propriety. Corpogeographies is a term that smooshes geography and body together.

When bodily expectations push against the limitations of normative beauty and health standards they ask: what kinds of bodies belong here? What should or shouldn’t they be doing? These questions are part of a long process of learning through my own embodied experiences, and are integral to my processes as an artist. I like making immersive sculptural spaces where fat bodies (and bodies that are othered in additional ways) can find comfort, and see representations of bodies that we have something in common with. To be represented and recognized is so powerful. This is why I have made rooms full of soft touchable textiles like Hungry Purse: The Vagina Dentata In Late Capitalism and the Maxi Pad Micro Cinema. Film and video are nutritious tools that offer ways to make fat recognizable and change some of the expectations attached to fat bodies as unlovable, inactive, desexualized. My own body is the place where I push against erasure and see if I can change the conversation.

Mike: You made a suite of movies with community activist Christina Zeidler before she took over the reins at the Gladstone Hotel. They feel easygoing and free, the two of you often appear in them, offering your love for each other as the basis of art, liberation, politics, transformation. In Glitter (1 minute 2003) you two visit a Northern Ontario farmer’s market and gas around, breaking moves and camping it up. In If Anyone Should Happen To Get In My Way (3 minutes 2003) you both appear in a variety of animal-cartoon-head-masks. The body feels like the site of change, the ground of understanding, a place where shame might be turned into new conversations, new joys even. Could you talk about your time together, the movies you made and how you made them?

Allyson: I met Christina Zeidler when we were both hired in 1996 as production assistants for an all-lesbian short film called Dog Days (40 minutes 1999) by artists Margaret Moore and Almerinda Travassos. It was filmed on Margaret’s parent’s farm in Consecon, Ontario. Christina and I hit it off fast and hard. We acted like idiots during the whole shoot — laughing and fooling around. We were a bit intoxicated by the dyke vibe on the set that included Shawna Dempsey, Louise Liliefeldt, Deirdre Logue and Johanna Tzountzouris as actors. Lorraine Segato from The Parachute Club stopped by and did some of the cooking. A-list lesbian art scene. Christina and I became good friends after that. We lived across the street from each other at the corner of Argyle and Northcote in the Parkdale neighbourhood of Toronto from around 1998-2002. We remain close. Christina is a really special person and very talented artist — she is also kind of feral and elusive. She edited and did the special effects for my video My Life in 5 Minutes (which is actually 7 minutes long).

In 2003 we went to the Banff Centre together for a thematic residency called Big Rock Candy Mountain. I was on the disaster end of a crash and burn relationship break up with Lex Vaughn and Christina was ready for something new and willing to do triage with my emotional train wreck. A true friend. I was in the phase when you are leaving a brutal relationship and fully heartbroken and empty, but also have the extreme pleasure and pain of being able to invent yourself outside of the hurt. We road tripped to Banff together and thrifted the entire way, gathering the materials that would become props in our future co-created films, like the stuffed animal heads used in If Anyone Should Happen To Get In My Way the matching leotards we wear in Glitter (1 minute 2003) and the doll that would become Unca Trans (5.5 minutes 2007). We solidified intentions for our filmmaking collaboration plans while we were in Banff.

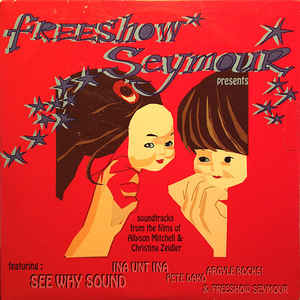

We decided to name our collaboration Freeshow Seymour after an immature childhood joke that we both shared but also because of what it called for in terms of access to making and seeing experimental queer film and video work and other cultural production. When we returned in the summer we got together for several makeshift retreats where we experimented with creating animation from still photography, puppets, and other objects. Christina was living in the country at the time. There were shoots that we creatively collaborated on and co-authored and there were also pieces where we assisted one another or worked in proximity. It was a very idyllic setting, in the rolling hills and farmland of Northumberland County. At the time Christina and her partner Deanne were lending their land to Sherry Patterson who was starting her own organic farm called Chick-a-biddy. There were tons of cats and dogs rolling around and we gave each other the support we needed to try out a bunch of ideas.

We would get together and explore our mutual crush on film. We worked hard for long stretches to try to bring to life tiny creatures, puppets made out of pantyhose and found teenage collections. It was really labour intensive and the general directive was to concentrate on the process and see what would come out of that rather than any kind of predetermined story that we wanted to tell. We used Holga photography, frame-by-frame super 8 using a built-in intervalometer, handheld 16mm Bolex and a rented animation stand from LIFT that seemed really high tech at the time. It was all about potential because most of the formats were blind processes. We had to wait for the actual chemical processing to see the pictures. This meant that the work, by necessity, had to be built on relatively low expectation and frivolity. We were articulating our shared energy, our obsessive attention to detail, our ridiculousness and finding the sublime.

When we got the footage back we would work through what the narrative might be, if there was one. Precious Little Tiny Love (3 minutes 2003) was created from some close-up, timelapse super 8 showing small toy animals nestled in gardens. The work’s meaning arrives through the lyrics and sentiment of the artist Melanie’s song I Don’t Eat Animals, which is a rumination not only on the politics of meat but also race (whiteness in particular), self-care, depression, biopolitics and food trauma.

In our collaborative film If Anyone Should Happen to Get In My Way (3 minutes 2003) we shot continuous gestural movement with emptied stuffed animals on Christina’s head using a Lomo camera that takes four frames per second of still photography. When we developed the work it was very striking and we used these stills as animation cells and reshot them on the 16mm animation stand at LIFT (Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto). We developed a loose narrative script about gendered rage, an inability to speak to betrayal, the emotional refrigeration of social norms that stifle expression. The animal heads are literally social masks. The repetitive gesture that the Lomography captures illustrates a sense of looped and stuck iteration and also the emotions of frustration or agony that comes from emotional suppression and arrested outlet. The music that accompanies the film is performed by Chip Yarwood and Celena Carrol and is meant to build a sense of doom and heaviness. The script lets the audience off the hook at the end by offering a pathetic self-deprecating joke. If you betray me and ruin me emotionally I might not talk to you on the street, so you better watch out!

In the fall of 2003 Freeshow Seymour had a collaborative screening with Pleasure Dome. We made a trailer. Christina’s band Ina unt Ina (Christina Zeidler and Celina Carroll) played and Pretty Porky and Pissed Off performed with live projection on spinning pizza boxes by The League — a feminist film collective. It was an evening that included not only the films we had made together but also those authored singly; although the bifurcation was not always clear because we had acted, edited, and collaborated on most of the work. Christina premiered her epic 16mm film Kill Road (13 minutes, 2003). The evening was not only single channel film though — it included performance, music, dancing and an ad hoc craft sale out of an old suitcase that held Pretty Porky and Pissed Off zines, stickers and small multiples (though I wouldn’t have called them that at the time).

Christina came back from Banff and began managing hotel renovations at the Gladstone Hotel. She began a long and supportive process of working with and amongst the existing clientele and community, the team of labourers and the newer users that the hotel was hosting, like experimental film screenings and alternative art and design fairs. My art studio was in the hotel.

I was a graduate student at the time and just beginning to realize my practice as an artist (rather than as a crafter — which is how I identified before going to Banff on an official artist residency). Christina and I were happily in each other’s proximity a lot during those days. We took versions of that Pleasure Dome screening of Freeshow Seymour on the road a few times with the help of Amy Kazmerchyk. We called it Deep Lez Film Craft. Piggybacking on travel for supported gallery and film festival exhibitions at sites like Frameline Festival in San Francisco, the Khyber Centre for the Arts in Halifax, MAWA (Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art) in Winnipeg, La Centrale Galerie Powerhouse in Montreal and Out On Screen (Vancouver’s Lesbian and Gay Film Festival). We also screened our film program at DIY film collectives in Portland. Our screenings were usually paired with performances at queer dance parties where we would dance Lazer Vag Magic to Chilliwack’s Fly at Night, Trans Ma’am to Bowie’s Fame and Bright White Sports Bras to Trooper’s Boys in the Bright White Sports Car. We would also conduct deep lez potlucks the following days where folks were invited to come and do a kind of show and tell of an artwork or idea that they were thinking about and we would collectively workshop how that art could be realized. These actions were definitely predecessors to the politics and practices of the FAG Feminist Art Gallery. As performers, Freeshow Seymour were not “good” per se — but we put a lot of heart into our queer cabaret, lez drag, and experimental dance karaoke performances. The body, our bodies, were the place where we tried to materialize some real and imagined transformations through a cornucopia of cultural offerings.

Swinging back to the beginning of this story and the site where Christina and I first met, it was at that Dog Days shoot where I also got to know Deirdre Logue. We ended up sharing a bed and didn’t get down or anything but we did laugh until we were in agony every night. Juist after returning home from this shoot I immediately ended a miserable and sexless relationship (my first one with a woman). Laughing myself to sleep with another woman seemed like a really great alternative. After all the Dog Days scenes wrapped up on that last day we all went for a swim in Lake Ontario and I paddled around with Christina and Deirdre. I had never been so manically happy. We were laughing so hard that if the water had pulled me down that day I would have died happy.

Kami: You do a tremendous amount of work in collaboration, often as co-director/filmmaker. Of course, filmmaking is largely a collaborative medium due to the workloads and technical demands. But the nature of your collaborations strike me as going beyond what is typical for most moving image artists. In particular, you have made many works with partners/lovers, and often the dynamics of these relationships structure and/or become part of the story the film is telling. Candy Kisses and your latest video, Her’s Is Still a Dank Cave (co-directed with Deirdre Logue, 24.5 minutes 2015), are exemplary works in this regard. I’m curious about how you came to work in this way, what continues to draw you to working in partnership, as well as your thoughts about the different ethics and methodologies of such a practice? How does this relate to what you refer to as “Deep Lez?”

Allyson: Deep Lez is a term that I came up with (with the help of Andrew Harwood) to describe some of the ways that I attempt to think through some of the histories of lesbian feminism with contemporary queer politics and practice. It is a term that quickly grew beyond my own practice and has been taken up by lots of folks who are interested in inclusive queer politics that don’t necessarily have to jettison lesbian from it’s clubhouse. For many it presents a paradox in holding on to lesbian ideas while fragmenting essentialized ideas about who is and can be a lesbian. This is a hive mind project that requires lots of opinions and ideas.

It’s true, I do a lot of collaborating. I rely heavily on the trust of the collective. Often it is because the scale of what I am taking on is beyond the capacity of one woman. This means DICK (do it with community knowledge) instead of DIY (do it yourself). I started working collaboratively from the very beginning with 3 Minute Rock Star which depended on a web of folks to produce a collective voice rather than one solitary genius or individual.

Many of my films express my rawest experiences with love and sex. I collaborate with lovers because artists are hot and there is something fundamental in our common purpose. I am attracted to people who are dedicated to things larger than themselves. I am also attracted to people who hold unique or atypical versions and visions of the world. For me it is all about the “feeling different” people. I make art with my lovers because artmaking is deeply personal, intimate and terrifying. I need a companion in the exercise of vulnerability.

I would call artmaking with my lovers elbow deep deep lez. The brainstorming never stops and we are in it together. Even in a break up film like Candy Kisses, which I made with Jane Farrow at the end of our catastrophic experiment with non-monogamy (sadly the same happened with Lex Vaughn and our catastrophic experiment with what I thought was monogamy), we created the dialogue together in the middle of the break. Beds are the place where queers come up with some of our best ideas for resistance and some of our most intimate hopes and fears can manifest into something else. The bed can be a site of lesbian resistance. How could we ever lose sight of this?

Kami: That’s a great question, how could we forget that the bed can be a sight of lesbian resistance? It’s a question that demands further consideration, especially when one looks at what passes for “lesbian films” on most of the LGBT film festival circuit today.

You’ve been making films and videos for more than two decades, as well as other forms of art including installations, sculpture, performance, and textile art. The technologies of film and video production, not to mention the fields of exhibition and critical reception, have shifted dramatically over this time, particularly with regards to the various queer cultural circuits, which include LGBT film festivals. While technologies have become increasingly accessible, allowing far more people to make the kind of DICK/DIY work you once had to shoot and edit on super 8 and 16mm film, conventional, homonormative and assimilationist work dominates what once were countercultural queer festival and cultural public spaces. In this context, you’ve mentioned that there’s not as much interest in queer artists making work. In your experience as a working artist, where does one find such spaces to exhibit now? Does the queer artist today have to create their own publics, like you did with the Lesbian Feminist Haunted House? How do you think about moving forward and making work yourself in this context, and what thoughts or suggestions do you have for other queer and trans filmmakers, not to mention curators and exhibitors of queer and trans work today?

Allyson: I don’t find any benefits from shifting technologies. The new stuff is cool but every time I switched to a different mode of film or video making to something I thought would be easier, it was actually harder. Computers kill me as much as the chemicals for developing film. It all takes the same amount of time, money, incubation and thinking. My scale of audience hasn’t really shifted since I was in my twenties when I made super 8 films. LGBT film festivals are gone. There is a difference between having a large audience for my work and a growing audience for my contribution. Do more people come and see my work? Not necessarily, but more people know my practice, know of my work, know of my contribution and its accumulation. As you get older, if you stick with it, that seems to be the pay off for Canadian artists who never had a market anyways.

The number of people who show up at your screening doesn’t necessarily reflect your impact or audience — that may be why queer filmmakers are not seen as valuable. Dissemination is easier through the internet, but none of my film and video work is available that way. I love the instant feeling of showing my life on Instagram, but it feels the same as making a giant haunted house. Making a meme takes as long as making a drawing or a short video or a needlepoint. There are only so many hours in a day and so much I can do with my hands and I have to do my paid job for most of that.

Supporting each other to make work is the only way I know forward. This is why Deirdre and I opened the FAG Feminist Art Gallery seven years ago. We were tired of shrinking scenes and spaces and the lack of opportunities to see and exhibit politicized work. I think that showing up to as much as you possibly can, asking what you can do to help, liking your friends’ posts and loving your friends work are the best ways to make spaces and hold them for others. I’m talking about throwing a wide net to catch the close queer family kind of friends, the crushes and the still-not-met yet. Yes of course artists have to create their own publics. They always had to and they always will. When we wait for this to be done for us it is always done wrong, it misses the mark and steals our precious activist energy.

To the last point of your question, curators and exhibitors and institutions need to work a lot fucking harder to contextualize queer/feminist/trans/BIPOC politicized work. There are so few people bringing the work into view. In my recent experience, it is the education programs in major museums, and not the curators (never mind acquisition departments) that champion artists who are interested in complex conversations around the role of art. Education departments are willing to be nimble and/or know how to leverage politicized art to engage publics because it is what people want. I have been to so many feminist/queer exhibitions and screenings that exceeded every kind of expectation for audience numbers and it always seems to come as a surprise to institutions, and it is always immediately forgotten when they return to business as usual. Paying attention to the work and connecting with artists is still very rare. We have to do it for each other. Like this.

Kami: I wonder if you could talk a bit about the thematic thread of imagining queer utopias that runs throughout much of your work. Unca Trans (co-directed with Christina Zeidler, 5:50 minutes 2007), for example, is a whimsical, animated “mockumentary” that purports to be an interview with a trans farmer looking back on his experience after the agrarian revolution. Her’s Is Still a Dank Cave was made a time when many queer theorists, such as Lee Edelman, and artists (including, arguably, Steve Reinke) are critically engaging the concept of queer futurity. It maps lesbian domestic utopias and directly engages with the text of Jose Munoz’s Cruising Utopia. What drew you to Munoz’s work, or to imagine these kinds of utopias and futurities?

Allyson: I made a t-shirt series that say “I’m with problematic” riffing on the familiar “I’m with stupid” t-shirts. I’m still trying to feel my way through the privileges I have acquired because I am a settler in Canada. I am white and cisgendered. Trying to unravel that is part of imagining a future where those subjectivities do not intersect with someone else’s oppression. Imagining our way out of cultural scripts are part of the process. Sometimes that is about telling painful truths and sometimes it’s about figuring out ways to continue on together from queer and feminist perspectives.

I was drawn to utopias (or just futures where we exist) from my depressing experiences in Women’s Studies classrooms. I remember coming out of undergraduate classes after learning about various power structures and oppressions and feeling completely hopeless. Not knowing how or when things could ever change. Part of the project of 80s and early 90s feminist classrooms were about trying to convince people that there is a problem and that feminism and social justice movements are necessary. At the time there wasn’t so much information available in class about resistance, social movements or the tools available to make change, particularly for people my age. Today, as someone who teaches feminist and queer theory, I talk to students about how it’s important not only to have a critique about the world but also to work to imagine how that world could be. It is their responsibility. Otherwise, what’s the purpose? Muñoz offers ideas about marginalized artist communities and movements that are about resistance and queer world making. There are others who do this work too, but for the project of Her’s Is Still a Dank Cave Deirdre and I wanted to explore the formal and fundamentally deep lez exercise of having a conversation between two queer theorists, one from 1970-80s (Monique Wittig) and one contemporary (José Muñoz). We wanted this conversation to occur off the page, poetically, using visuals, performance, special effects and music.

Muñoz and Wittig are two dead authors that we use as fuel to work backwards in time. They remind us that queer time is also an impossible time. This is what Christina and I (in collaboration with Bobby Noble and Vlad Wolanyk in writing the script) are evoking in Unca Trans. We were trying to express the potential for intersectional queer politics right here and now, but it is so hard to describe the present moment. For us, it took imagining a future queirdo like Unca Trans telling us about ourselves right now. Our generation has an irreconcilable theoretical division in queer and feminist theory between the second wave and the new wave that both Muñoz and Edelman are pointing us towards (and older waves that never made it to the surface but we dig through for inspiration and learning about now). This is the dilemma that Deirdre and I attempt to feel our way through in Her’s is Still A Dank Cave, all the while trying to understand queer family, our relationship to furry animals, our partnership and our purpose.

Works Cited

Edelman, Lee. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

Kirby, Vicki. Telling Flesh: The Substance of the Corporeal. New York, NY: Routledge, 1997.

Lindgren, April. “Lesbians to Protest Raid on Pussy Palace: They Thought It Was ‘a Safe Place to Be Themselves’.” National Post October 27 2000: A20.

Longhurst, Robyn. Bodies: Exploring Fluid Boundaries. New York: Routledge, 2001.

Mitchell, Allyson. “Corporeographies of Size: Fat Women in Urban Space.” Thesis (PhD). York University, 2006.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: New York University Press, 2009.

Movies

3 Minute Rockstar. Producers. produced by Allyson Mitchell and Jane Farrow. 1996. Super 8 to video.

Chow Down. Dir. Allyson Mitchell. Vtape, 1997. Super8 to video.

Dog Days. Dir. Margaret Moores and Almerinda Travassos. Vtape, 1999. Video.

Fallout Food. Dir. Tracy Tidgwell and Lukas Blakk. CFMDC, 2004. Video.

Free! Bake! Sale! Dir. Allyson Mitchell. Vtape, 2004. Video.

Glitter. Dirs. Allyson Mitchell and Christina Zeidler. Vtape, 2003. 16mm.

Hers Is Still a Dank Cave: Crawling Towards a Queer Horizon. Dirs. Allyson Mitchell and Deirdre Logue. Vtape, 2016. Video.

If Anyone Should Happen to Get in My Way. Dirs. Allyson Mitchell and Christina Zeidler. Vtape, 2003. Video.

My Life in 5 Minutes. Dir. Allyson Mitchell. Vtape, 2006. Video.

Precious Little Tiny Love. Dir. Allyson Mitchell. Vtape, 2003. Super8 to video.

She’s Real: Worse Than Queer. Dir. Thane, Lucy, 1997. Film: Vimeo: Web. March 22, 2017. <https://vimeo.com/12084539>.

Unca Trans. Dirs. Allyson Mitchell and Christina Zeidler. Vtape, 2007. Super 8 to video.

Footnotes

[1] Big Judy was developed for Mayworks—Festival of Working People and the Arts, in the spring of 2004. The script was co-written by the members of Pretty Porky and Pissed Off: Joanne Huffa, Abi Slone, Mariko Tamaki, Tracy Tidgwell, Zoe Whittall, and Allyson Mitchell. For more on Big Judy see my chapter “Big Judy: Fatness, shame and the hybrid autobiography” in Embodied Politics in Visual Autobiography, edited by S. Brophy and J. Hladki (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014): 75-90.)

[2] Mitchell, 2006 #2016