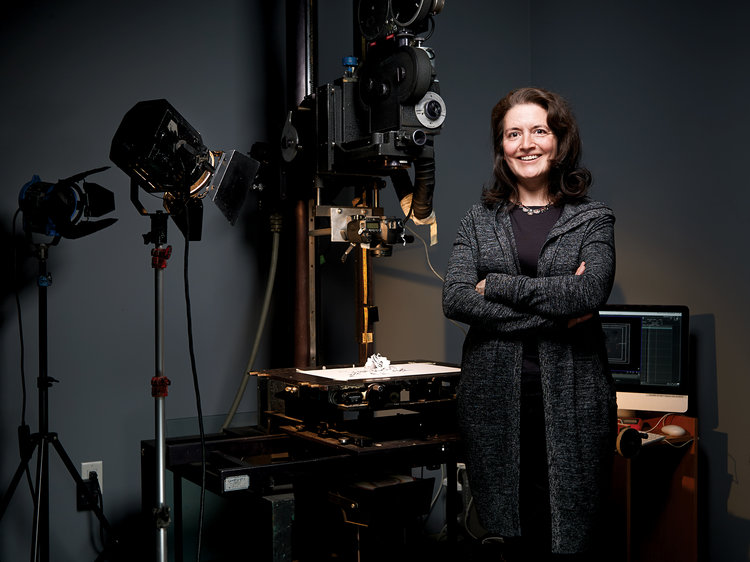

Trust: An interview with Franci Duran (2010)

Mike: Were pictures always important to you? When you were growing up (was it here, in Toronto, or in the other place where pictures come from?) were there already pictures you longed to become?

Franci: Pictures are tremendously important to me. Lately, I like to take them apart and then rebuild them again. I have very few pictures from my childhood. My family left Chile after the military coup in 1973, and our photographs were left behind. Our belongings were stolen or thrown away after our home was ransacked. I hardly have memories of this time.

My paternal grandfather, Mario Duran, was a civil engineer by profession, but also an amateur photographer who took a lot of pictures. He had a Leica, and built his own darkroom. I think the darkroom was an escape from his terrible marriage and provided a temporary reprieve from his six children. After I went to film school, I realized that his photos were not only concerned about the people he loved, but highly structured and composed. He also took super-8 movies. Those were left behind in Chile and then lost too.

Mario was missing for two years, and was already dead, but we didn’t know that. He had driven off a cliff; his smashed car and body were hidden in a valley. There was no reason to suspect political motives, as Pinochet was no longer running the country. Mario was diabetic, he drank a lot, he was depressed and took antidepressants. He was a terrible driver. Even though the crash was labelled an accident, I think he probably killed himself. A mountaineer found the car. His body had been preserved by the dry heat, so he looked like a mummy (without the cloth wrapping). I remember a shrunken brown face with a shock of white hair.

Two of Mario’s photos:

1. I am standing alone in a field of grass, two years old and barefoot. The photograph is horizontal, seven inches by four inches. I am drawn to this picture because of where I am in the frame, top third, left, small. But also because when he printed it, he wanted me to appear as if in a swath of light, in contrast to the darker texture of the grass. But the area I’m in is much lighter than the rest of the grass. The photograph has an oddly digital look, as if someone’s taken the Photoshop Lasoo tool and applied a contrast curve too quickly and without thought. It’s an unsuccessful experiment.

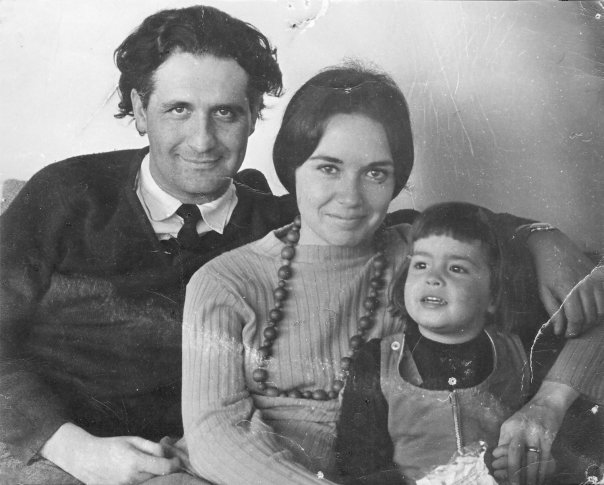

2. The photograph is eight inches by ten inches, horizontal, close-up. My parents are about to kiss. My mother’s face covers about 2/3 of my dad’s. It’s quite stylized and reminds me of an eclipse. When I look at the photo, it doesn’t look like passion, but restraint.My mother is attractive, but she looked terrific when she was young, especially in black and white photos. My grandfather took some great pictures of her and my dad. We have some, my maternal grandmother had some, while others made their way back to us. We weren’t completely without family photos, only the ones from our house. Some of these pictures accompanied me to university, then to my various Toronto, Kingston and Vancouver homes.

I’ve just posted one of them as my Facebook profile pic so you can see it. This one is taken right before we moved to London (my dad did a post-doc at the University of London). It shows my mom, dad and I. We are seated on a sofa in my grandfather’s house. They are staring at the camera, I’m looking at something else. They look amused, not quite annoyed yet. I like it because of the cracks and push-pin holes in the physical (now digital) photo. It reminds me of where I’ve lived.

But the photo I’m thinking of is not one of those. It shows my mother and my brother Andres, and it was printed in the Montreal Gazette on October 8, 1973. My mother looks very genteel. She is dressed in a fur coat and she’s bent over, zipping up Andres’ snowsuit. I don’t know where she got the snowsuit or, now that I think of it, why she thought she needed a snowsuit for him in early October. Was it really that cold? Or was it a metaphorical coldness? The framing is pretty tight. Andres’ face is squished into the hood of the snowsuit which is cinched tight, but his eyes seem unnaturally big as he stares right into the camera. Reacting to the flash maybe? The headline read, “Les Yeux De L’Exile” (The Eyes of Exile).

My parents, my brother and I traveled in the first planeload of Chileans before Canada’s refugee policy was in place. We weren’t technically refugees, though they gave us a special designation. We arrived in Montreal, which as you know was highly politicized at the time. Rene Levesque was there to greet us, along with various Quebecois radicals, and of course there were reporters and TV cameras. This led me to wonder if there’s footage of my family in an archive somewhere.

I emailed French CBC to request a search, but was told there wasn’t any footage of Chilean refugees from the mid-seventies. But I didn’t believe them. I remain convinced that I didn’t request the material in the proper way. I don’t think it is possible that they don’t have footage of Chilean refugees, although of course it is probable that they don’t have footage of my family stepping off an airplane.

This pursuit put me in touch with Heaton Dyer, a friend of my brother’s and a producer at the CBC. He authorized an internal search for the footage. Many emails later, I found out that if the material exists, it is stored in one of 6,500 badly labelled film cans archived at a storage facility outside of the CBC building in Montreal. To have an archivist look through them would be expensive, and if the archivist found anything, a union editor would have to be hired and a suite with a flatbed rented to look at the films, as the CBC no longer has flatbeds.

I asked if I could look through the cans myself and was told: “They found the French news line-up for that day. The story was dropped from their show and there’s no sign that the visuals exist. End of the line from our end.” I really want to get into that storage facility. So much of our visual history is just sitting there, probably waiting to be thrown away. (I love the CBC. But it is somewhat impenetrable if you don’t know your way through that thick bureaucracy.)

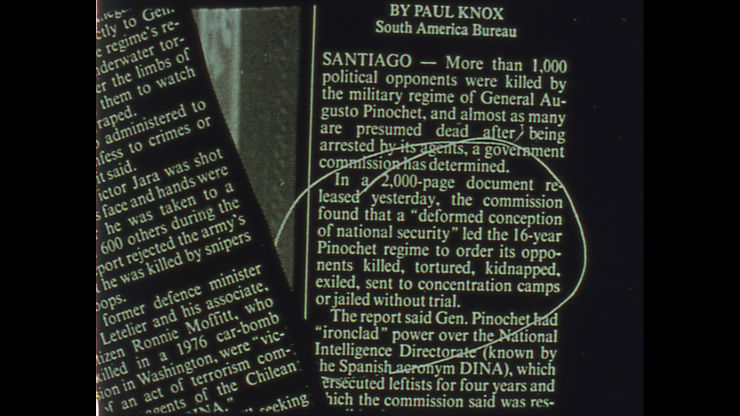

Mike: There is a chilling moment in Bob Woodward’s Veil, where former CIA director Richard Helms recounts a September 15, 1970 meeting with American President Richard Nixon. Nixon fumes about the possibility of Marxist Salvador Allende winning the democratic election in Chile, and orders Helms to take action, offering 10 million in cash. Helms understood the true motivation behind the executive execution order. When Nixon was a young lawyer working in New York, one of his first great clients and patrons was Donald Kendall, chairman and chief executive officer of PepsiCo, which had a bottling plant in Chile. Woodward notes, “The anti-Allende operation was essentially a business decision.” It led directly to the CIA-sponsored assassination of Allende and the installation of military dictator Augusto Pinochet.

Franci: My focus on the artifact is linked to my own early childhood and my family’s exile. I came to Canada as a refugee at the age of six, but have very few tangible memories of that time. Since 2003 I have been working on a film series entitled Retrato Oficial (Official Portrait) which deals with the historical reach of the now-deceased military dictator Augusto Pinochet. The latest film in the series, which currently in development, is divided into three visually distinct sections that, in turn, consider Pinochet’s first address to the Chilean nation, pursue the difficulty of historical recording and retrieval (particularly at the CBC archives), and treat both the problem and promise of the archive.

The personal experiences of my own family serve as a foil to these investigations. When I was 21 years old, I tried to find the super-8 films my Grandfather shot over the course of 15 years. These films document my father and his five siblings. This footage was left behind in Chile following the coup and stored at various people’s homes. I went back to Chile but was told it had been lost. All that remained was one reel. I was disappointed, but happy that a single piece remained. But when I had the reel transferred, it was not family footage I saw, but a Charlie Chaplin film. Because of the number of times I have moved since I was 21, I have since lost that Chaplin film (and the transfer). After losing the remaining piece of my grandfather’s archives, and unable to recall which Chaplin film it was, I purchased a substitute on eBay, an 8mm print of The Immigrant that I’ve optically printed sections from.

When I started the MFA program at York University, I directed my attention to transmigrating the work I had been doing on Super-8 and 16mm film to digital video. In 2003, I made Lala (3 minutes, 2003), a video that documents the transformation of a single image. I scanned a family artifact, divided it into sections, created zoomed-in (10-12) images from each section, then layered each file in a digital editing program.

When my mother and her siblings put my grandmother (who has vascular dementia) into a home, my mother took on the task of archiving the photos and documents that were in my grandmother’s possession. I sifted through these and came across a photo, taken in 1910, of my great-great-grandfather, my great-grandmother, a baby (my great uncle) and the maid or nanny. It is a curious tableau. My great-grandmother and great-great-grandfather are looking away from the camera, perhaps at each other. The maid’s gaze is directed at us. My great-grandmother wears a fabulous plumed hat. They are outside. In the distance stands an out-of-focus figure, perhaps a policeman or a soldier. It is unclear whether the scene behind them is a backdrop or not. The video is titled Lala because one of my grandmother’s caregiver was named Lala, and coincidentally, so was my grandmother’s wet nurse. In the video, this connection is recounted in voice-over. My mother can identify every person represented in the photograph except the woman who meets our gaze. The missing identification provoked by the photograph rhymed with my interest in lost, irretrievable moments. Because my grandmother has dementia, and none of her siblings are alive, or well enough to remember, I had no way of finding out who this woman is. I assume she was a maid or nanny because she is wearing an apron and because she is mestiza, of mixed race. These are the obvious implications of class and race in Chilean society today and historically, and this is partly what Lala explores.

Mike: Your movies reconvene archives large and small, straining public pictures through the necessary aperture of family. They are grounded in a lived, political understanding but their unusual form ensures that their audiences will be mostly specialists, fellow seekers and artists. Don’t the questions you raise about the disappearance and murder of so many people under the long dictatorship in Chile require a more public interrogation, a more familiar form of address?

Franci: Chilean-Canadians who have seen my movies connect with the images and storytelling, Cuentos de mi niñez (Tales from my Childhood) (9 minutes 1991) and Boy (5 minutes 2005) have made some Chilean Canadians cry, if that’s what you mean. They unwrap a yearning for what was lost, and what I believe was a beautiful, if unachievable, dream. Chileans (in Chile), on the other hand, tend not to connect with my work. They find it unnecessary and needlessly sentimental. They’ve moved onto other matters.

When I show films that are not directly about Chile some people ask me why I’m not making work about Chile. When I tell people about the current Pinochet project, I’m asked why I’m still making work about Chile (and Pinochet). I try not to worry/think too much about this, or I become stuck.

I’m interested in pursuing Chile (and Pinochet) again because I find the fact that there are still people unaccounted for (who “disappeared”) to be unacceptable and a block to democracy. I’m also interested in how people accepted these disappearances, embraced Pinochet, and allowed him to stay in power. Look at Spain. Even 40 years after Franco’s death, there’s a refusal to unearth past crimes. Spanish Judge Baltastar Garzón’s career is in jeopardy for daring to open up mass gravesites and revisiting unresolved human rights abuses committed under Franco’s 40-year regime. How do we allow this to happen? Why this resistance to look at this?

My work tends not to resonate with a lot of people and I know this is a problem. I don’t think very much about audience response when I’m making work. When I was working on Mr. Edison’s Ear (32 minutes 2008) at York University, Phillip Hoffman said I shouldn’t think about audiences at all, and Laurence Green said I should think them more. Who is right? Probably both of them.

When Mr. Edison’s Ear screened at the Hot Docs festival, it was interesting to look out into the audience and not recognize everyone. The crowd was primarily there to see Korbett Mathews’ The Man Who Crossed the Sahara, a documentary about Canadian filmmaker Frank Cole. My film was the opener. I fielded difficult questions about choices and content, and received comments like, “Your movie is very poetic, I had no idea a documentary could be like a poem.” Of course, I love the community support that we get at smaller screenings, but there is value in seeing how a work stands up to an audience with more conventional tastes.

My next film will be longer. I plan to integrate more interviews and bring my inquiries into the present, to look at the current refugee bill, the recent earthquake in Chile, the changing nature of archives, and how “disappearance” is handled in the news now that the news is driven by the internet. I’d like to interview a pathologist who works with human rights cases. I’d love to interview Garzón, who was the judge responsible for Pinochet’s indictment for human rights abuses in 1998.

My friend, hairdresser and sometimes collaborator, Paul Sheppard, told me the following story. He has two childhood friends who became filmmakers. One works in TV, the other is an installation artist and art-based filmmaker. The TV-friend phoned up Paul and told him about the art-friend’s latest movie, a documentary that follows a woman in Saskatchewan who is a diviner that practices water witching. The TV-friend praised the movie for its cinematography, inventiveness and attention to character development, but when asked if he liked it, he replied, “Well there’s one huge problem: She doesn’t find water.”

My friend Jennifer Bain, who works as the food editor for the Toronto Star, said something like, “Then there is no story. He should have killed it.” Lynne Fernie, a doc programmer, said: “You wouldn’t believe how many entries we see where they find water.” Laurence said something like: “That film is obviously a character portrait about the journey, and that can be valuable, as long as a clear inner struggle is established, and the appropriate arc is followed.”

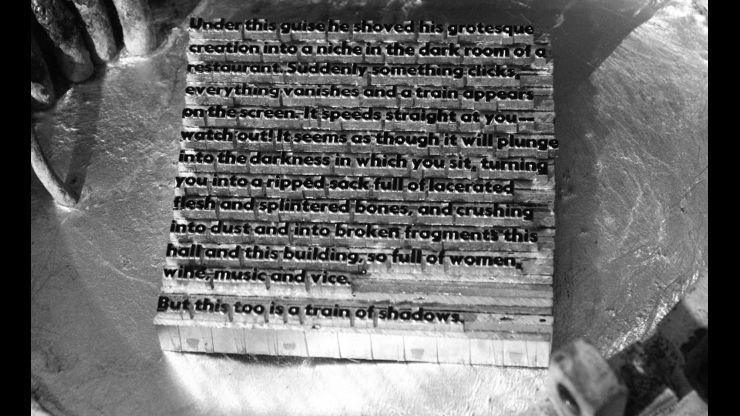

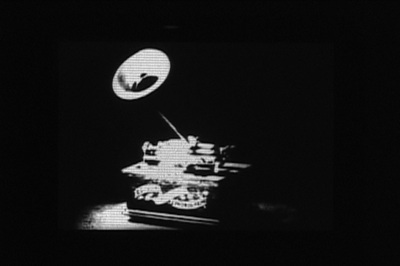

After the “Film is Dead! Long Live Film” screening at the Cinematheque, James Gillespie told me that my film, In the Kingdom of Shadows (5 minutes 2006), had moved him. He used to work as a typesetter/compositor in a print shop and was very familiar with the Ludlow Linecaster, which is the machine I show in the movie. Molten lead was poured into letter moulds, then arranged by the compositor into lines of type. When the lead hardened, these were removed and you wound up with a positive impression, a physical line of type. These are then inked and put on the press and finally onto paper. I love these lines of type because they exemplify a loss, maybe of a time before the digital, when type still had a physical body. When you could run your hand over a page in a book and feel the impressions, the presence of the physical process of printing and the link to the history of movable type (and literacy).

In the Kingdom of Shadows documents a block of type (showing Gorky’s review of the Lumiére Brothers first screening) melting into a pool of lead in a single shot (well almost, there’s a dissolve) that reconsiders historical and technological relationships between cinema, print and review. James said that the film touched him because he always felt a sadness for the words, stories and meanings that disappeared as the lead was recycled or discarded in order to become new texts. This isn’t about Chile, but certainly about language, meaning, and maybe a showing of scars?

Mike: Yes, why not the movie as scar, memorial tract, or evidence of an operation? In Boy (5 minutes 2004) you say in voice-over, “I have lived in four different cities, and each one has claimed a piece of me.” We enter a rain enshrouded city, the frame filled with the simple joys of looking. A slowly moving hail of abstract nights lights precedes a slow motion birth, recoloured and rephotographed from a TV screen. Your voice offers up a series of dates along with the facts that accompany them, your son’s favourite book, animal and word (No). As Jacob’s mother, you are a storehouse of memories that he doesn’t have. His memory is external to him, in this sense, the experience of motherhood is like the experience of a film, another form of externalized memory. Each instance of looking feels like it has been run through your fingers, precious and luminous and crafted with the whole body. And it arrives in fragments, there is no story to pull it all together, unless it is the story of memory itself, with its necessary omissions, its shorn away pieces, remnants, left-overs. The formal experimentalisms and material fetishes that inform this movie, and much of your other work, appear here as an analogue for memory itself, and as a gift of seeing, an inheritance of seeing in the dark. It makes me wonder: is every film the mother of its audience?

Franci: Boy was made as part of a Cineworks (Vancouver film co-op) omnibus project that was never assembled as a whole. The theme, “Vancouver at the turn of the century” (or something like that) was selected by the producer Eva Madden. John Price and Angelique Crowther were part of the group, I can’t remember who else. Eva had some trouble that year, she was very depressed I think, and moved back out east so the whole program was never assembled into a single movie. It was supposed to be completed in 1999 in time for the end of the millennium.

In June 1999 we moved back to Toronto. Then Tomas, my second boy, was born and I left the movie until 2004, when I finished the sound and lab work. But the movie is essentially the same as it was in 1999.

I originally proposed a portrait of the park in the middle of Strathcona (we used to live across the street, directly on the park on Hawks Avenue). I was going to shoot for a set amount of time over a set period of a few days, always in the early mornings. I have never been a good sleeper, but when Jacob was a baby, I was often up early, and spent a lot of time looking out our front window. The park had a beautiful life, a quiet stillness and serenity in the early morning with the elderly Chinese men and women walking around the park and doing tai-chi, the odd parent and toddler, dog walkers. Other times it was more chaotic…

Jacob was born in 1997. My friend Lisa Doyle filmed Jacob’s birth (on high-8). She took some still pictures too. I know I did not have this moment documented just so that Jacob would have a record of his birth (although now he does), rather, I knew I would use the footage some day.

In the first two years of Jacob’s life, David was in architecture school at the University of British Columbia which is very demanding, and in the summers he was at work doing small renovations or doing on-set carpentry for commercials and Movies Of the Week. He wasn’t around much during the day. I spent a lot of time alone with Jacob, and with other mothers and young children. Being with a very young child changed my perception of how time passes. I loved and hated it. I used to think that I was busy, and there was never enough time to get things done, but after Jacob was born that changed. I would get “work” done (design jobs, housekeeping) when he was napping. When he was awake, time could feel excruciatingly slow. For instance, walking to the store which was a block and a half away from our house, might take 30 minutes if I let Jacob’s desires dictate — a one year old can become fascinated staring into a puddle, or lie down in the middle of the road. It’s not linear or “productive.” I was forced to slow down, and came to see Vancouver from another perspective.

During that period Jacob choked on a penny when we were in a café on Commercial Drive. I didn’t know it was in his mouth or even that he had a penny. I looked over and saw he had fallen backwards, unconscious, and he was grey. We (the people in the café and the two mothers I was with) knew he had choked. For the next minute we were all in a panic trying to get him to breathe again. That minute felt very long. It was very long.

I changed my movie to reflect what I was living at the time, the perception of time spent caring for a very young child, and point toward other cities I’ve lived in. It’s a love poem for all those things, I guess. And maybe because love is complicated, the movie is imperfect… I allowed it to remain somewhat unfinished and raw. It should have been a longer movie, to reflect the way I was experiencing time, but I’m not going to add to it.

(I didn’t have Tomas’ birth filmed, but I do have a collection of one-minute shots of Tomas during his first few months of life. I was going to make a movie or installation called One hundred days of baby. I shot 20 moments over 20 consecutive days, then maybe 10 other minute-long moments scattered over a couple of months, because I became so busy with the unpredictable day-to-day of a very young child and baby. I would realize a few days later that I had forgotten to film the minutes I had meant to. I never pieced these together because I became upset that I had been unable to follow the discipline of my original highly structured intention. It’s a good analogy for parenting actually.)

I have a lot of pictures of Jacob from that time. Like other parents, I photographed him obsessively. This was a way of connecting with him, maintaining intimacy, while allowing him to do his own thing, to move and explore as he wanted. I shot very little actual footage of Jacob for that movie. I mostly filmed the city on rainy days because that’s how I experienced Vancouver. I developed this immunity and (complicated) love for the crazy rain that you can’t escape (sometimes it would fall upwards and into my useless umbrella).

I wanted everything in the movie to move (like time and film). Most of the cityscape shots I used are framed out of a moving car. The opening shot was made on Hastings Avenue through the front windshield of our truck, then optically printed. I thought everything should look wet, and melt or dissolve. Vancouver is wet. Birth is wet. Toddlers are always leaking fluid of some kind… Jacob was in the car with us when those shots were taken. The birth footage worked with that too, and I like how the roll bars show the discrepancy between video and film time. Optical printing allowed further explorations.

The soundscape and narration have something to do with the acquisition of language. I don’t have a positive association with learning English because it is tied to the loss of my early life in Spanish. Neither of my kids speak or understand Spanish, even though I tried to speak it to them when they were babies. But it felt like an intellectual exercise, not like parenting should, and I really wanted to feel connected to them. So the narration is in Spanish and English, and not always translated literally/perfectly/exactly because that is the nature of translation.

Mike: She Was So Young Back Then (3 minutes 2002) offers a close-up look at a pair of women eaters, repurposed from television. Your looped material reworking suggests a shared secret in the look that joins them. Can you talk about this movie, and your offering up of this fragment?

Franci: It was made for a film festival designed by Roberto Ariganello, former director of the LIFT film co-op. In order to kick start production, he dreamed up the $99 Film Festival, featuring expensive ideas and cheap materials. She Was So Young was supposed to be part of a trilogy looking at 1980s teen movies made by women. The movies were all about teen sexuality, relationships and fitting in, typical North American middle-class teen girl angst issues. But my three source movies are different than, say, John Hughes teen flicks. They’re edgier, while still being mainstream. For instance, Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982) deals with abortion (among other things) and Smooth Talk (1985) deals with sexual assault. I was a teenager in the 80’s and loved these movies, watching them over and over.

I only finished two: She Was So Young Back Then and Does This Mean We are Going Together? (from Valley Girl (1983) directed by Martha Coolidge). I wanted them to be displayed like “peep shows,” contained in a booth that you’d look into. Maybe I’ll make the third one this summer or perhaps I should stop thinking of them as a series.

The excerpt in She Was comes from Fast Times at Ridgemont High. The scene I documented finds Phoebe Cates showing Jennifer Jason Leigh how to give a blow job using a carrot as a prop. It was shot off my television set onto super-8, then optically printed onto 16mm. When the film came back, the frame lines jumped up and down, and had this irregular, stuttering kind of rhythm. This was due, I guess, to the S8 film jumping in the JK projector as it advanced, or maybe the JK Bolex was not working properly. I liked the effect of this accident because of the reference to motion/action of a blow job as well as to the awkwardness of adolescent inexperience. The rephotography prolongs the look that connects the two girls, providing a visual demonstration of the act of looking and longing.

Mike: In Retrato Oficial (4 minutes 2009) you conjure a country which permits only a single picture: a full length portrait of its ruler. Copies can be made, details enlarged, but no deviations are permitted. As Benjamin famously remarked, facism aestheticizes politics, while communism politicizes aesthetics. Your surveillance myth of a picture that looks back from each artist’s hand, resolves in the first broadcast of Pinochet immediately following the coup, in which he suspends the parliament and the courts. Your feeling for the tactile (or so it seemed to me) couldn’t resist granting even this picture a fractured digital beauty, which led me to wonder about the place of the hands, the touch, in a medium as remote and far away as the movies, which are commonly viewed in an unmoving darkness, as if we didn’t have bodies at all. Or the legacy of touching that a dictator leaves across a generation, as economic shock tactics are so often coupled with state torture, as Naomi Klein chillingly observes in her must-read bestseller The Shock Doctrine. Your material concerns seem to wrestle with the dictator that lives inside your fingers, as if the body and the body politic were the same somehow, as if it were necessary to oppose the decades-long military occupation in Chile on every level, including the level of the material signifier, the film itself, newly grown and luxurious in your careful treatments.

Franci: The fable is an excerpt from Raul Ruiz’s essay Images of Images. Ruiz is a Chilean filmmaker, mainly of dramatic features, though his filmmaking practice led him towards pictures which have gained historical importance, both for the country and for myself. The rights to the original footage of Pinochet’s first address to the country belongs to Patricio Guzman, the Chilean director of the documentary La Batalla de Chile (The Battle of Chile). The address was originally filmed at the Comandancia del Ejercito on September 11, 1973 and broadcast on TV Nacional (TVN) which remains a public TV station. This broadcast was shot by Guzman (on 16mm from his TV) on the day of the coup, and this is what appears in Guzman’s film. I telephoned TVN hoping to find out how much this footage would cost to use. It was very expensive, though I learned in subsequent conversations that the original broadcast master was missing. The new original has become the 16mm footage made by Guzman. The copy has become the original.

The painting is a portrait of Bernardo O’Higgins Riquelme (he is the “ruler”) who is known as the “great liberator” of Chile from Spanish colonialist rule, after the Spanish War of Independence ended in 1818. He was also Chile’s first “Supreme Director.” Pinochet was a great admirer of O’Higgins, and strove to create an association of himself as a liberator, leading Chile away from Communism.

The image of the painting I downloaded for the video is the one that hangs in the Comandancia del Ejercito. It was painted by Francisco Jara Quinonez who was probably inspired by the Gil de Castro (“el mulatto Gil”) portrait of O’Higgins which I really like. The Cubist reconstruction is based on one of Picasso’s Harlequin paintings. I used downloaded material to in order embrace and examine the artifact. The unpleasant, ugly, but present artifacts of digital images. It creates a prelude and approach to the Pinochet speech, making it visible again.

Mike: Mr. Edison’s Ear (32 minutes 2008) is your longest movie to date, part Edison biography, part technology essay, turning around the deaf inventor of the phonograph. It is punctuated by multi-screen animations, moving text displays, and his own short subject movies that offer a rich tableau of circus performers, staged battle scenes and a child born away by a great black bird. These carefully excised moments are punctuated by interview briefs by a trio of media historians and archivists. Lisa Gitelman offers up this observation: “I think of the spoken voice in that period as the standard of ephemerality. It was the thing you couldn’t keep. Sure, you could have a newspaper reporter or stenographer try and write down what somebody said but there was really no keeping the voice. And with the phonograph there is. I don’t think people made a direct connection, that may have, on some deep symbolic level, offered a level of compensatory stability in a period of profound change. Amidst all the loss involved in social changes, cultural changes, and economic changes, here is one moment that offers a preserve-ability, something to cling to.”

Once again, like Benjamin’s angel of history, you are walking backwards, searching for the roots of reproduction. There is a keening pleasure in materials here, everyone you show looking back at the camera from a century ago is already dead, and you touch these faces, these gesturing, stammering, dancing bodies, with an extraordinary delicacy. It is like watching a very patient mortician in a room filled with her dead care. As these old frames flicker back into life, there is something like an old fashioned wonder in the act of looking at anything at all. To watch two men walk across the street, for example, and see how one approaches the other, and pause for a moment. What a miracle of expectation and mystery this shot is. Or at least: your representation of this shot. You dig into these old frames until you can find your own roots in them, and show them as if you had made them yourself, the issue of your own hands and seeing. What propelled you to make this movie, and how did you attach these scratched and faded frames to moments of your own life?

Franci: I had set out to make a film based on artifacts: three sound recordings made onto wax or celluloid cylinders. It would be an archeology or perhaps a disinterring. I wanted to chronicle the excavation of three stories recorded on cylinders dating from the turn of the last century: a recording of an aboriginal language; a recording of early music; and a recording made for the purposes of either commercial or political propaganda. These three categories were my initial attempt to classify these recordings. I was interested in exploring the physical cylinders themselves, the technologies that activated them, and the sounds people were first interested in preserving. I hoped that this investigation might consider what it is about sound that made it so desirable to capture, represent and preserve.

Cylinders are the physical storage objects onto which sound was recorded, and also the objects from which sound was played back. Imagine a vinyl LP shaped like a hollow tube. Cylinders were placed onto the rotating drum of a phonograph. As these rotate around the fixed axis of the spindle, sound vibrations would be carved onto the surface of the cylinder by a metal stylus. The cylinder is inscribed with a picture of sound. During playback, the process is reversed, the stylus reads back the carved image and projects sound from the phonograph horn. The oldest existing recording, Charles Lambert’s Experimental Talking Clock (1878), was written onto a lead cylinder.

I began to build the first story around some Onondaga language recordings owned by the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), which date from either 1902 or 1903. I saw these as points of origin for the recording industry, and useful for examining the ongoing results of colonialism and the mechanism of propaganda. The Ethnology Department at the ROM sent the CBC cassettes of their collection of Edison wax cylinders containing voices of Iroquois speakers telling stories and singing songs. The CBC based a segment of a radio series on these wax cylinders and called it Iroquois Voices. The show stated that the difficulties in translating the recordings were due to the scarcity of people who could speak the languages. In fact, this is not the case, there are people on the Six Nations Reserve who speak each of the six Iroquois languages. The translation/transcription problems were due to the quality of the recordings. Since their involvement with this project, members of the Six Nations reserve have been able to reclaim a number of previously lost stories and oral histories and have put these to use in their community. This difference in the description of the problem directed my interest towards the differences in archival practices between the ROM and the Woodland Cultural Centre and the CBC.

I visited the Six Nations Reserve and the Woodland Cultural Centre where I interviewed Amos Key, the Director of Language Programs. My visit had a profound effect on the outcome of the thesis that eventually became Mr. Edison’s Ear. I was particularly struck by a story that Amos Key recounted in order to demonstrate the differences of opinion within his community regarding preservation. The Cultural Centre typically displays antique wampum ceremonial belts. A group of elders wanted to use the belts in a ceremony — as they had for generations — and liberated them. After the ceremony, the belts were simply returned to the exhibition case. This practical and spiritual use of the belts caused controversy within the community over their value as useful and historical display artifacts.

Unfortunately, it became overwhelmingly difficult to secure permission to use the Onondaga/ROM recordings and to obtain the required permissions. To properly address the racial and moral issues of colonialism would have required collaborative work, and neither the ROM nor the Woodland Cultural Centre were interested in pursuing the investigation much further. So the video took another path, one that veered toward a more direct inquiry into the nature and recording of sound.

As my project unfolded, I began to focus upon technologies of inscription. I was already interested in the origins of artifacts and memories, in translation and in the transference of objects and experience across generations. This has to do with the way things move, especially in things we cannot see, like sound. How do you make an accurate picture of sound? How do you graphically represent something you cannot see so that you can keep it, or even sell it?

I began to notice and document films where sound vibrations are inscribed — albeit temporarily — onto a liquid’s surface. In Walt Disney’s Snow White, the main character is relegated to servitude by the evil step-queen, and sings as she cleans. These vibrations of joyful song travel through the air and come to play across the clear water, which only a moment ago revealed her reflection. The song is illustrated by the gently rippled surface of the well’s water. New waves appear, disturbing the first, until another voice arrives — the prince who joins her in song. In It’s All Gone Pete Tong, alcoholic, hard living and recently deafened Frankie Wilde realizes he can have his life as a DJ back when he sees vibrations in his scotch. He devises a system of seeing sound using contemporary computing technologies to translate audible sound into visual waveforms. The result of his effort is an awe-inspiring musical performance unlike anything anyone has ever heard. Finally, in Jurassic Park, a close-up of a child’s glass of water, the surface vibrating wildly, announces the impending arrival of something large, scary and unexpected. It is the first indication that a T-Rex is coming (and marks the arrival of digital compositing in movies).

Every video has a secret life that describes its making. Mr. Edison’s Ear took more than three years to complete and has taken many twists and turns. From the Onondaga recordings to Snow White, I found myself turning towards Thomas Edison. He was trying to invent a machine to record the Morse code of telegraph signals. But he found that the recording, when played back at a high rate of speed, would emit tones. He realized that sound could be recorded.

One of the connections I hoped to establish in the video is between the phonograph, the capture of sound, and my fictionalized Edison’s body. The prioritizing of sound as the experience of hearing, and the rooting of this experience as auditory perception, establishes a circuit linking listeners to technology and back to the body again in a multitude of patterns. I was fortunate to capture (on video) Hodge’s anecdote of how a mostly deaf Edison auditioned performers by biting down on the edge of his recording phonograph. He would judge the singer’s quality according to the vibrations he felt. Mr. Edison’s Ear might be built around this recorded tidbit. When I told this story to Dr. Kenneth Norwich, the physician and engineer who appears in the video, he replied, “There’s a story about Helen Keller, which I just thought about. Apparently, even though she could not hear or see, she nonetheless enjoyed opera. What she would do is bring a wooden crate to the theatre and sit on that crate and through vibrations somehow experience the music.”

This description of sound as a tactile presence prompted me to then inquire how the experience of hearing occurs physiologically, specifically, what happens once the auditory nerve receives the information that causes us to perceive the sound as hearing. The preoccupation with his body that my Edison exhibits is associated in my mind with the phonograph that, as Tom Gunning identifies, captures and separates sound from its source. Thus, as my Edison wanders through the collection of material I have pieced together for him, I wanted him to seem lost, like a ghost wandering among remnants. These remnants and ephemera were created by successive technologies and now exist in different archival formats.

Mr. Edison’s Ear makes use of text as an image of sound. I have manipulated found type, or text in the video, in order to do work on the subject of deafness. I wanted to illustrate deafness through the space that surrounds the written word. I wanted, as the poet and typographer Robert Bringhurst puts it, “to produce a state of reading/being in the viewer: There are always exceptions, always excuses for stunts and surprises. But perhaps we can agree that, as a rule, typography should perform these services for the reader: invite the reader into the text. Reveal the tenor and meaning of the text. Clarify the structure and order of the text. Link the text with other existing elements. Induce a state of energetic repose, which is the ideal condition for reading.”

I took excerpts from Edison’s diaries, and tried to distill them into poetic fragments. Edison’s writing is both lengthy and comical. We always read type as images and patterns as our eyes traverse the page. I wanted to show this process and draw attention to the visual beauty of the single word, even the single letter. Writing is the solid form of language. It was important to remain true to the original typesetting of the book containing Edison’s diary excerpts. The Diary and Sundry Observations of Thomas Alva Edison was typeset in Baskerville, a typeface designed by John Baskerville in 1750, an inventor in his own right, who established the shape of the book page (and in particular the academic book page) in the 18th century. This standard remained in place for over a hundred years.

The project treats Edison’s personal and corporeal understanding of deafness as crucial to his invention of the phonograph. Historically, the video explores how the phonograph functions as a metaphor for the pain of entry into modernity. The video is a collage of contemporary technologies and archival sources most of which originate from the five-million-piece Edison archive.

I am continually drawn to “found” images. Images from another time have another life, no doubt other meanings. This inclination of mine has to do both with pleasure and a sense of disquiet not fully abated. What is the truth of an archival image? Can the archive be trusted? What really can be trusted?