Shooting Indians: An interview with Ali Kazimi (2010)

Mike: What role did film play in your formative years?

Ali: My father was the General Manager for Kodak’s New Delhi operations, so I grew up in a middle class, largely English-speaking family. The Kodak showroom and office was on the ground floor and we lived in an apartment on the third floor. My sister Anjum and I would often spend time in the office after the staff had gone. We would play with the security guards and drivers who lived on the premises. We were surrounded by Kodak marketing materials, life-sized cutouts of white women in bikinis holding the latest Instamatics in their hands, group photos of cute puppies, and the much sought after Kodak calendars.

The warehouse was at the back of the office. Here the orders were shipped, not only in cardboard boxes neatly wrapped in brown paper, but also in wooden crates. For us, the air of mystery was heightened by the aroma that enveloped the packing workshop, a heady mixture of wood and photo-chemical smells occasionally laced with the very pungent aroma of mustard oil, which the guards used to cook their dinner. Even today, when I smell the Indian hard woods teak and salt, I am immediately transported back to that shipping area. There was a huge walk-in freezer, strictly a forbidden zone for us; occasionally we would catch a glimpse of the frozen world and feel the icy air within when someone was sent inside to prepare an order. I digress, but it was a magical place.

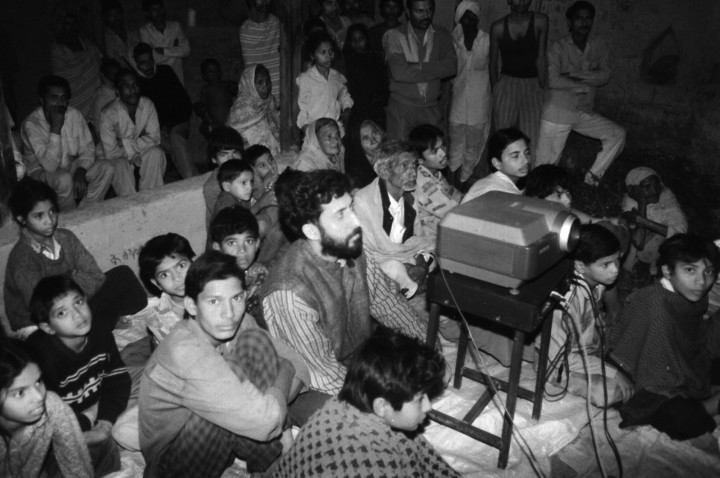

In the sixties and early seventies, India had a fairly closed and protected economy. Anything foreign, however mundane, was rare, thus expensive and much coveted. Delhi was the only city with television broadcasts and the single government-controlled broadcast was restricted to three hours every evening from six to nine. We did not own a television until I was fourteen, instead, radio dominated our home, particularly since my mother was an announcer with All India Radio’s Urdu Service.

We had an old tube radio and we’d all gather round and listen to her show when she was on. I had a nanny, very much like my surrogate mother, who would tell us our mother was actually inside the radio. I have a vivid image of peering through the slits of the radio watching the glowing lamp of the tube filaments. It was a strangely mysterious place and I could almost imagine her in that world. Soon after I’d graduated from high school, my mother encouraged me to audition for the English youth service and I was accepted as one of announcers. I proceeded to host pop and rock music request shows, and also did current affair arts docs in a series called The Roving Microphone. We were expected to do field recordings and interviews, and then work with an experienced producer and editor to pull a show together. This was a time when editors physically spliced 1/4” tape; in order to get a voice to fade they would gently brush the emulsion away. Watching these guys at work was truly astonishing. I did that for three years, and it honed my interest in documentary.

Live radio was absolutely terrifying. There was a large analog clock, and when the big red light was on it was live, and I was alone in that room. Each show was monitored by a duty officer who listened carefully to every word. One day I signed off by saying, “I’m going home folks,” followed by a song called Going Home. When I left, I found out that the duty officer had filed a report against me. He’d taken great exception to my closing remark. Why does the audience need to know where you’re going? You’re not being professional and serious. His presence was a constant reminder that we were working on a government-run radio show, inside the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting.

I was much closer to my father than my mother. He was a very open-hearted and generous man, often drawn to sentimental gestures. I remember when soft ice cream machines arrived in Delhi. It was a big treat for us to drive to this place. Many street kids were there begging, and he bought everyone cones. The kids ate in shocked silence, while the vendors assured him they hadn’t eaten for days. Why don’t he give them money? My father replied, “I want them to have a treat like my kids. I want them to have this special moment.”

In the English-medium private schools I attended, it was expected that one would either become a doctor, lawyer, engineer, an executive, a businessman or a civil servant. Looking back now at my high school colleagues, this was an accurate prediction. When I was eleven, my life took an unexpected turn. My father was killed in a car accident and our family’s economic and social condition instantly worsened. Life would no longer be the same, though it took me many years to realize the magnitude of this loss. He was 39, I was 11.

Because he had been a corporate executive for Kodak, we were living in a fairly posh neighborhood. The company allowed us to stay on for six months, and then we had to move to a lower middle class neighborhood in the “government quarters.” Since my mother was an announcer working for the ministry, she was entitled to a government apartment, but within the hierarchy of officialdom she was on par with mid-level clerks. Delhi is a brutally class-conscious city, particularly in the middle class. My father’s death had been very traumatic, and the cascade of events that followed built on that trauma. A few friends told me that their parents no longer wanted them to associate with me because of where we were now living.

Since I was the eldest of three siblings at the time, I inherited the cultural trope of, “You’re the head of the household now, son.” It took me a couple of decades to recognize how I hadn’t really been given the chance to grieve for my father. We were on vacation when the crash happened, and according to Muslim tradition, the burial has to happen in 24 hours. He was dead, buried and gone, and we had no participation in the rituals surrounding his death. I’ve become acutely aware of how absolutely important that transition is, the ability to say good-bye. For many years I felt this was all a bad dream, that he’d gone off somewhere and would return.

When he was alive, we’d go for long drives and, as he was an Anglophile, he would often quiz me about statues of British monarchs that were still around Delhi at the time. When the statues started disappearing, it was rumoured that treasures were hidden in their pedestals. Years later in Toronto, as I was coming to terms with my father’s death, I would walk around Queen’s Park. It reminded me of Delhi roundabouts. I made my way to the statue in the middle of the park and froze. It was the same statue of Edward VII on his horse that used to be next to my school in Delhi, one of the statues my dad would quiz me about.

My interest in art and photography emerged out of his library, located in a small bookshelf in our drawing room (old British terminology still lingers on in Indian English). My father’s books shaped me completely. I spent most of my childhood happily flipping through the pages of the Annual Journal of the British Photographic Society, which was stacked next to Time-Life books on natural history. Other shelves held work on early cinema and Shakespeare on film. Even after he died, he continued to talk to me through his collection of books.

In 1974, at the age of thirteen, I picked up my grandfather’s 1940’s Kodak Brownie and went to the Delhi zoo to take my first set of photographs. Later that year, my friends and I set up a rudimentary darkroom in the bathroom, my father’s former colleagues gave me the chemicals. We scrounged around and found some white enameled metal trays, and even a red light bulb. The windows were blacked out and we stuffed cloth under the door to keep the light out. Later that day we processed our contact prints and watched with awe as our first photographs appeared on a piece of paper.

I went to St. Stephen’s College in Delhi University and graduated with a respectable Bachelors of Science degree in Physics, Chemistry and Math. I was not only involved in the Photographic Society — running the darkrooms and entering competitions — I was also active in the Hiking Club. This mountaineering society undertook twice annual, month-long expeditions in the Indian Himalayas.

At the English language youth service, Yuna Vani, of All India Radio, the government-owned and operated station. At Yuva Vani, I learned not only to write for radio, but was mentored in story telling while creating short radio documentaries.

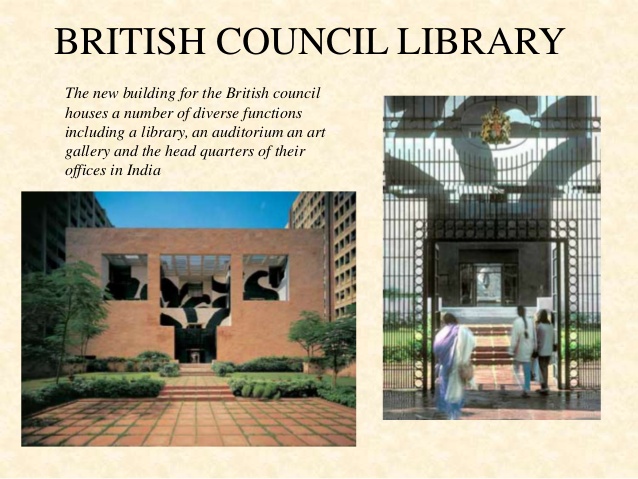

During the course of my studies I had won a few photography awards at University competitions and freelanced for magazines. But it was only after graduating that it became clear to me what I wanted to do. Photography was my calling. Meanwhile, I scoured flea markets with friends for back issues of National Geographic and photography magazines. Or else we would walk to the British Council Library or the American Library to look at the latest issues. I became one of the tens of thousands of budding photographers whose goal became to shoot for National Geographic. My friends, of course, thought I was stark raving mad, as did their parents, who often sat me down to caution me about the impossible odds of making a living doing what I wanted. My own family worried about my choice but never held me back, nor did they force me to choose a safer path.

Ironically, by this time I was already frustrated with the limits of still photography. I realized I wanted to tell stories, and to engage with the world by bringing to light social issues and problems. I had by then been exposed to newly emerging independent filmmakers such as Anand Patwardhan, who had made a film about the attempts by Indian (mostly Punjabi and Sikh) farm workers to unionize in British Columbia. It was deemed harmful to the bilateral relationship between Canada and India and pulled from the Indian Film festival. It was inspiring on many levels and made me feel even more strongly about documentary filmmaking. I had no idea how I would achieve this goal, and of course I had no idea that it would bring me to Canada.

I joined the best possible program that would get me there: a graduate course in Advertising and Public Relations, which had one course in filmmaking. This was my first foray into the world of the moving image, but it was far removed from issues of social justice and I could not connect with the idea of devising adverting campaigns to sell soft drinks in rural India…

At the same time, Canadian filmmakers James and Margaret Beveridge were setting up a new graduate program in filmmaking, in Delhi. It was the closest thing to a film school in the city. I applied and was one of the privileged few to be accepted. Jim Beveridge was mentored by the legendary John Grierson, the fiery Scottish filmmaker who not only is credited with having coined the term “documentary,” but also for founding the National Film Board of Canada. My colleagues and I were shown many of the classic NFB films. It was an immersion in Canadian filmmaking. The Canada we saw was a largely European country. Our Canadian instructors, we observed, had accents somewhere between the American twang and drawl and the clipped Oxbridge British accents. They, in turn, were often surprised by our familiarity with Western popular culture and technical competence.

Six months later, I was one of the two students chosen for an exchange program with York University. Two graduate students would come from Canada. This would be my first trip outside India. In August 1983, I flew from Delhi to London, where my family was now based. The degree to which I had been acclimatized to English culture and references struck me when we landed at Heathrow. There was an unexpected sense of familiarity that was both reassuring, yet at a core level deeply unsettling. I felt colonized.

Two weeks later we landed in Toronto; and we had an unexpected welcome waiting for us. A uniformed officer asked us to step out of the immigration line. He examined our Indian passports and Canadian student visas and asked us to follow him into his office. In a bare room, across an empty desk, we were grilled for what seemed like an eternity. He was not sure if our papers were in order. How did he know we had not bought them in some back street in Delhi? We were stunned and vehemently denied doing any such thing, and launched into a detailed explanation of the exchange program. He seemed unimpressed.

“Why don’t you call our professor, Jim Beveridge? He is waiting for us outside,” we suggested.

“Where is all the money this letter says you have for your scholarship? Which suitcase is it in?”

We were both shocked at this questioning and reiterated our position. He suddenly stopped flipping through the empty pages of our passports and handed them back. “The only reason I am letting you into my country is because you speak such good English.” He stamped our arrival in Canada and handed us our passports. “You will always remember me,” he said with a smile.

Well, I have no recollection of what he looked liked except that he was white, clean-shaven and middle-aged; but I have to thank him for propelling me on a voyage of engaging with Canadian immigration history. I became fascinated by the power of the immigration officer, literally the gatekeeper to a country. A fundamental question started bubbling as I made myself more familiar with Canadian immigration history. If Canada was a such a multicultural, tolerant and welcoming society, why were Canadians overwhelmingly of European descent? Why were second-generation, Canadian-born, Indian children inevitably asked “Where are you from?” Why was the Indian diaspora overwhelmingly from the Punjab and mostly Sikh?

In the fall of 1983, I was in Toronto, not knowing that a new chapter in my life was beginning. Along with my colleague Premika Ratnam, I made films that received awards and we were given the option to stay on. At this stage, a respected Indian filmmaker visited us for a heart-to-heart talk about our career choices. He said there was no way a student from India could break into the Canadian film business, let alone make a career. The only place this was possible was in India.

I knew that in India video technology was exploding, my colleagues in film school were being snapped up by the newly emerging commercial television. India offered many possibilities, but for the kinds of films I wanted to make there was little interest, and even if they could be made the hurdle remained of where they might be shown. Apart from all this, I felt I needed to learn more and chose to stay on. There was a price to pay for this. Even though I had come as a graduate exchange student and had chosen to do undergraduate courses because they were better for production, York University refused to recognize my degree from India. For them, it was equivalent to a high school diploma. My colleague and I fought this for a year with very supportive professors, and lost, but I chose to stay on because the scholarship would be extended, and in filmmaking a degree does not matter.

The next few years were challenging and exciting. The student films that I worked on offered a wide range. There was a film shot in a maximum security prison that examined a treatment program for sexual offenders, a film about the psychological impact of the threat of a nuclear holocaust on kids, a look at the life of a Native photographer. With each film I entered new worlds. I learned not just about other people, but about myself. This is the very nature of documentary.

After film school, making a living in film was not easy. Add to this the overall difficulties of cultural difference and race and the odds are multiplied. Throw in self-doubt and it began to seem that the naysayers were right all along: it was impossible. An early lesson I learned was that you cannot enter documentary filmmaking for money or security. It is a wild and often unpredictable ride. If you choose, as I did, to tell your own stories, then you spend most of your time raising money, pushing paper for applications, and precious little time doing creative work. The reward is that you are allowed to create and generate your own work, developing your unique perspective and point of view.

In 1985, I watched Canada convulse with hysteria and panic when a ship arrived off Newfoundland carrying Tamils fleeing the civil war in Sri Lanka, then a year later when a shipload of Sikhs claiming refuge from political repression in Punjab arrived off the coast of Nova Scotia. Two responses struck me: the kindness of communities on whose doorstep the refugees landed and, on the other extreme, the often viciously racist opinion pieces published in newspapers. The Canadian government response was hysterical in the second instance. Parliament was recalled from summer recess to deal with this apparent national emergency, and a restrictive immigration bill was passed. There was much talk in the media about queue-jumpers and the need to control immigration. The language was coded, there was much talk about due process, but underneath I felt a deep unease and anxiety about race and national identity. I doubted very much if the same reaction would be elicited if a ship carrying white refugees fleeing post-apartheid South Africa had arrived.

Over the next six years my colleague and I would encounter many immigration officers, as we first sought to renew our student visas, and then decided to apply for permanent residence. Some were kind, others officious, and a few were like the one we met on our arrival.

In the spring of 1986, I got my first job editing a documentary in Vancouver. At first glance, Vancouver seemed almost as diverse a city as Toronto; in reality, I found it to be disquietingly segregated. Downtown and its immediate neighbourhoods were overwhelmingly white. Chinatown in downtown Vancouver and the Punjabi Market on Main Street were the only exceptions. The suburbs were distinct and concentrated: the largely Punjabi South Asian community was in Surrey and Abbotsford; the Chinese were largely in Richmond.

Mike: Can you talk about the most common documentary portal – broadcast television? Any thoughts on the past and future of this home diversion?

Ali: Television is wave-like, it’s designed to have a continuously hypnotic and insidious effect. The waves arrive in the material’s shaping. Everything is aimed towards the commercials which structure each program.

I directed docs that were part of a reality TV series. I was a hunter-gatherer who had absolutely no control over how the material would be shaped. The footage was handled by story editors who came from the drama department. They would massage the tapes into five acts and three storylines, each with an appropriate back story. The classic tropes of fiction film were transplanted and superimposed onto documentary material.

The shows were set in hospitals, and I met patients who had seen previous shows that helped familiarize them with the hospital, and what kind of engagements worked with the doctors. There was an upside to it. On my darker days, I felt it was truly exploitative. In fact, there was a level of pornography in watching patients go through medical procedures. But then you’d meet patients or parents or kids who insisted that it gave them a certain measure of confidence and comfort. The hardest part was treating it like a job, to engage with patients in order to develop a relationship of trust that would allow us to follow them through complex surgeries, often the most transformative moments of their lives. The position of the interviewer becomes very powerful, it is almost akin to a confessional. On the other hand, people are very media savvy, we do a huge injustice imagining they are grist for the mill. When people agree to be part of any film there is an unwritten contract. There are many unstated intents on both sides, and as much as we’d like to make them explicit, often we don’t know the full intent of why they choose to be in our films. For patients undergoing medical procedures, one of the unstated motivations was that having a camera crew witnessing their procedures meant the medical system would have to be at its best.

Most of the time I never watched the shows, I didn’t want to feel the pain and frustration of losing the ability to deal with the material as a true director. I was a director in name only, while the producer and editors put it together in the edit room. I finally gave up doing the series after watching a couple of people die. The doctors and nurses, the cinematographer and sound recorder were engaged technically, but I had no task that would add a filter between what was happening and what was being recorded. They were transformative and amazing experiences at one level, but at another level difficult to process.

I didn’t grow up with TV in India. We had one government-run channel that would come on for three hours in the evening. But when I came here, I became an avid consumer of North American media. India was going through a huge flux at the time, there was a separatist movement in Punjab, and violent events were reported almost daily. I saw how India was being represented, and the consequences of that representation in interactions with my colleagues. The India on North American TV was an India of victimhood, of clichés, of the British series The Jewel in the Crown. Warm Raj nostalgia was contrasted with senselessly violent Sikhs. India, along with the rest of the non-Western world, was presented as a place where people did not have the ways and means to make sense of their lives, hence the necessity of intervention by the west.

When a reporter does a “stand up” in an Indian street, a direct address to the camera, they’re typically filmed with a long lens. Behind them is a swarm of pedestrians and crowds, and the long lens squeezes everything together in a crowded mass. This technique wouldn’t be used if the same reporter was addressing the camera in London or Berlin.

I began looking at my own stereotypes around Native peoples here in Canada that came to me from the spaghetti Westerns I saw as a teenager. One afternoon, while driving north with one of my professors, I caught myself asking if there were any real Indians left. He went into a long explanation about lost Native culture and assimilation, and how there were no full-blooded Indians remaining. I started reading a lot, and rang up a remarkable Native elder who invited me to come serve soup at Council Fire, a drop-in centre for homeless people she was running. I hung out and talked, our point of engagement was that we were all Indians, that proved a good icebreaker. I wondered how I might represent the complexity of urban Indian life in Canada without myself resorting to gross oversimplification and generalization?

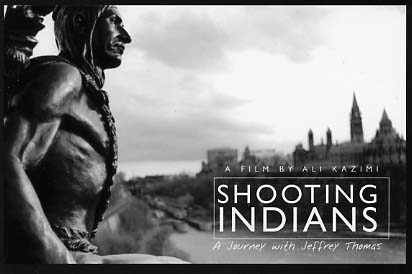

Then I came across a magazine dedicated to Native artists called Sweetgrass that had just started publishing, and found the work of Jeffrey Thomas. He was directly taking on questions of Indians past and present, photographing powwow dancers in traditional clothes while introducing playful interventions. Someone wearing traditional clothing stands next to a sedan. Another applies face paint in a mirror with a pink panther decal stuck in the corner. I called up the Sweetgrass editor and arranged a meeting with Jeffrey. We were both very nervous. He couldn’t believe that someone would want to make a film about his work when he himself was still trying to figure out what he was doing. I felt that he and I had something in common. We were both self-taught photographers, and admired the work of some of the great photographers, mostly American. And we shared an outsider sense of alienation, as he says in the film, that’s what finally allowed him to participate.

It took me a long time to see Jeff as a disabled man dealing with a very serious injury that forced him to live with constant, at times truly debilitating, pain. He had broken his neck in a car crash, and while he couldn’t move in his hospital bed, he wasn’t given treatment in time because hospital staff thought he was malingering. Just another lazy Indian, the nurses whispered. Because they didn’t catch that injury, it left him with partial paralysis. This was an incredible athlete who had professional football dreams, and overnight he had became someone who walked with a cane and a limp. Here was the profound impact of stereotypes, tragically embodied. He’s very stoic about it, he doesn’t draw attention to it, and it hurts him to watch himself on screen as a result. It forces him to confront the way he actually moves.

I began the film as a student, and it was difficult to raise crews because people had stereotypes about “Indian time” and unreliability. I remember speaking to the Dean of Fine Arts at a reception and telling him that I had just visited a Six Nations Reserve. He replied, “How very exotic. Tell me, what was it like?” Native reality seemed so far removed from the realities of mainstream Canada. I recently showed the film to a graduate class in anthropology and one student said that the Canada on view is an alien landscape, a country he didn’t know existed. This is 26 years later.

I didn’t want to make a film that mirrored what many western filmmakers had done in India, which was to make superficial work about people on the margins of Indian society. I was engaged in constant questioning all the time. How was I going to frame Jeff, what was he going to be wearing? He was my interlocutor, and while I felt I could access his urban community, I didn’t want to make a film that would be anthropological. It wasn’t going to be a film about Jeff and his people. He was an artist dealing with issues of identity and representation which in many ways represented my own emerging quest.

Jeff’s great aunt, Emily General, had played a pivotal role in his life transmitting culture, as grandparents often do. I interviewed him after their visit, and he was struggling because she had just told him that he had to learn the Onandaga language. Why hadn’t he learned his own language yet? Why is he making pictures? He tried to explain his position as an urban Indian with roots in both the reserve and urban centres, and that photography was his language now, but she didn’t want to hear that.

His marriage fell apart while I was shooting the film, and this became a huge crisis for me because I didn’t have enough material. His wife Monica was a theatre actor and I knew her quite well. I didn’t know how to make meaning of this break up which left her in such despair and therefore I didn’t know how to deal with Jeff. In the ensuing years, I would occasionally meet his son Bear, who told me that I should go see Jeff when I went to Ottawa. We met seven years later and it was really great to see him. He had persisted in his determination to confront the stereotype of the noble savage with photography. In our years apart, I had been working on a film called Narmada: A Valley Rises, and I used everything that I had learned and reflected upon in Jeff’s work in my own representation of the indigenous people of India. I caught myself circling around ideas of “the pure tribal,” a term even activists used. The suggestion was that deep in the country’s interior one might encounter “real tribals” wearing loin cloths, carrying bows and arrows. I remember undertaking a trip and catching myself with this question: what am I doing? I felt I was in a trance, once again seduced by clichés.

Jeff had started working at the National Archives, where he’d been given the task of naming First Nations people from their large photographic collection. These pictures had been given captions like “squaw” or “warrior,” and he was charged with the task of finding familial relations, names, or whatever details he could muster. That’s when he watched the rough cut of the film I had made seven years before, and he saw what had become archival footage of himself. He was struck by the power of these pictures which showed an urban Native experience that remained virtually undocumented because it wasn’t “authentic.”

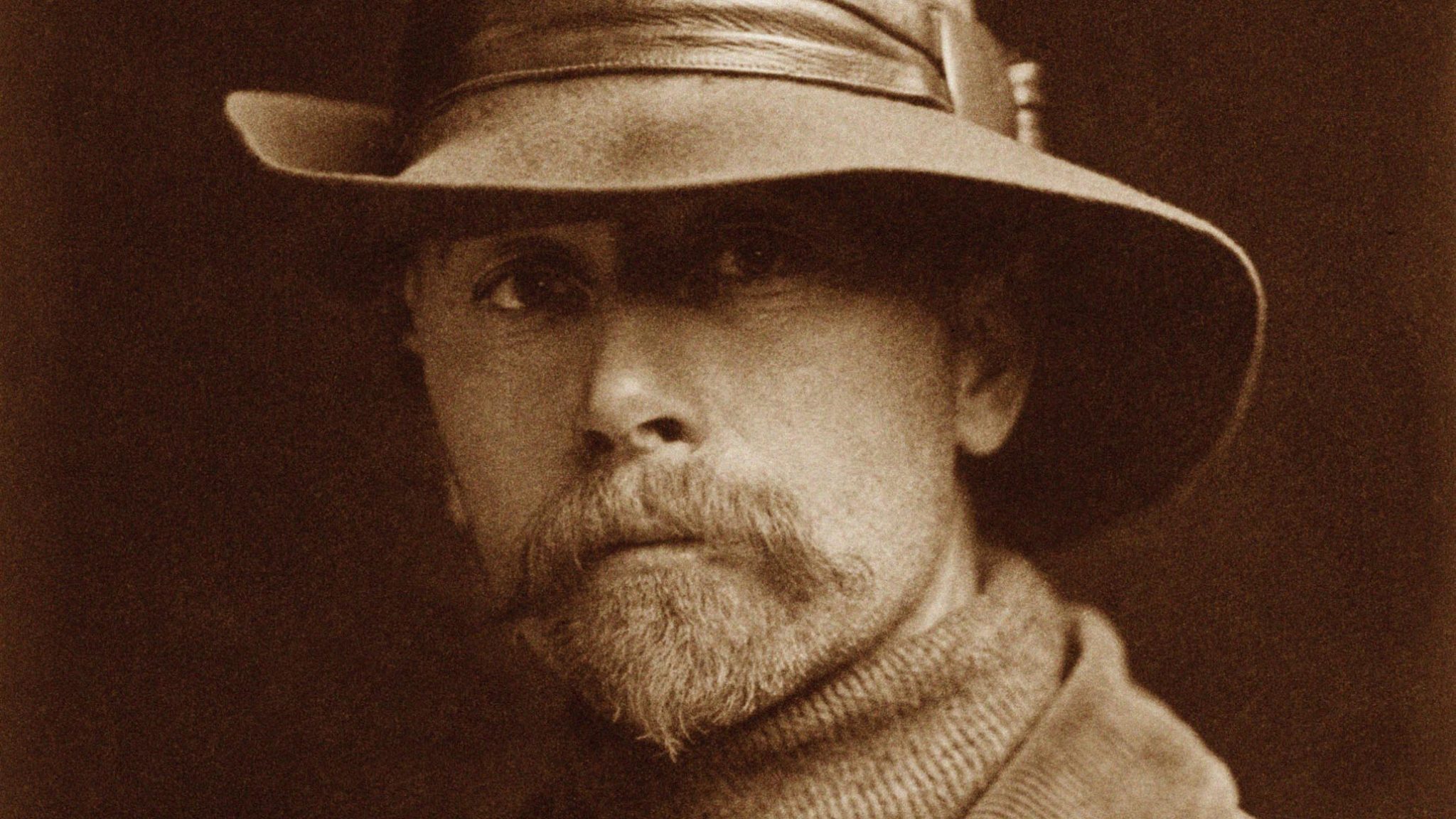

Our mutual inquiries hovered around the work of Edward Curtis, an American photographer working at the turn of the century who had spent over two decades photographing mostly Native Americans in a project he called The Vanishing Race. In the 1980s, Christopher Lyman went back to the original negatives and compared them to the prints, and showed how Curtis removed any markers of modernity or contact with the white man. Curtis became a lightning rod for the anger of Native artists, and Jeff had joined in this outrage against the photographer and the creation of the noble savage image. But when I met Jeff a few years later, he had immersed himself in Curtis as a fellow photographer, and was newly receptive to the complex interactions between Curtis and his Native subjects.

Mike: Can you talk about Narmada: The Valley Rises (86 minutes 1994)?

Ali: When I was at university I befriended a number of self-taught photographers like myself, one of whom went on to become a leading environmentalist photographer in India, Ashish Kothari. In the early 1980s, he formed one of the first environmental groups in Delhi. His group organized a walk through this amazing river valley in central India, the Narmada valley, and wrote a report on an impending disaster which most people in the country hadn’t even heard about. There was a proposed dam, funded by the World Bank, which was going to displace hundreds of thousands of people.

After living in Canada for seven years, I visited India in 1990 and rang up Ashish. He said that Medha Patkar, one of the key activists in the movement, would be in his office the next day, did I want to come and meet her? We met and talked for about an hour, then she looked up and asked, “How committed are you to this?” She told me to meet her at the train station that evening. I went back to my sister’s place and told her that I was going on a trip and didn’t know when I would get back. There was much concern and anguish for my safety because I was heading into remote areas. I boarded the train with Medha and she gave me a tutorial on the entire history of the region. She was a trained sociologist who had come to the valley to do field work for her PhD and stayed on. At two o’clock in the morning one of the activists traveling with her whispered into my ear, “Fall asleep. She’s not going to sleep unless you fall asleep.” I thought I was going to be incredibly rude, but I closed my eyes and pretended to sleep. “Oh look, he’s tired,” she said and then promptly fell asleep. That was my introduction to her.

I spent ten days criss-crossing the valley. It was an India I knew existed but had never experienced at that level. I attended planning meetings about a large political action that would see several thousand people walking 250 km in a non-violent protest against the dam, beginning on Christmas day, 1990. It was now mid-October. I came back to Toronto and tried to raise money, but I was primarily known for my work as a cinematographer. Raising money for a struggle that seemed remote even in India was very difficult. I rented the first professional Hi8 camera that came into the city, then flew back to Delhi. I hired a sound recordist and a camera assistant and we began filming the next day. I left five weeks later, at the end of January.

There was a lot of anxiety about someone completely unknown showing up with a camera. There were no private broadcasters, and the idea of police surveillance cameras was just arriving. Following the same pattern that has preceded each of the G8 summits, there had been a lot of fear mongering in the press, the protesters were described as criminals coming to destroy the dam, sensationalist stories about explosives were circulated. This predictable framework allowed the state government to mobilize a huge security response. I decided I would stay close to Mehda, as well as Baba Amte. Baba came from a wealthy, land owning family and had been quite the playboy. He used to drive a red MG, write film reviews and corresponded with Greta Garbo. One day he came across a man dying in an advanced state of leprosy. He was horrified and ran away, but he couldn’t sleep. Deeply ashamed, he returned, picked up the man and brought him home and tended to him until he died. Baba was an incredibly strong man and a remarkable figure. He took a liking to me as well, so I had strong connections to the leadership. With both Baba and Medha there was a sense of class familiarity, along with our ability to converse in English. There was clearly a limitation to this approach, but I didn’t feel I had time to connect with every aspect of what had become a very heterogeneous movement that included labourers, indigenous people, and large land owners.

We marched from the middle of the submergence zone, the area that was going to be turned into a giant lake once the river waters were stopped. Submergence zones happen to be where valleys are narrow, you need high walls of gorge or mountain range to contain the waters that will collect behind the dam. We started in the middle of the zone, in what is some of the richest agricultural land in India, in a state called Madhya Pradesh. We marched from this state to the neighouring state. Linguistically and culturally, the two states are quite distinct, but even more distinct are the Adivasis, the indigenous Indian people, “the tribal people.” There are two tribal groups: the Bhils and the Bhilalas. Like all indigenous people, they have been pushed to remote and inaccessible areas, and because of this they’ve managed to retain their way of life, language, culture, in fact their entire societal framework. To this day there’s a strong ethnographic, almost Victorian, approach to photographing the “exotic” tribal peoples. Like the urban Indian in Canada who is not seen as authentic because they wear contemporary clothes and live a contemporary life style, I felt the same thing was happening with the Bhilalas in India, who in their appearance were often indistinguishable from other rural people.

Tom Waugh had written a piece in Cineaction where he argued that in the Indian documentary, it was the group shot that dominated. Given tight knit communal frameworks, people felt more comfortable speaking in groups. The one-on-one interview was a western conceit that came out of the confessional, and this couldn’t be transposed on India. One of my goals became testing Tom’s thesis, doing a lot of one-on-one interviews, though these only started once people knew who I was, a couple of weeks into the march.

We marched to the dam and were stopped at the interstate border. A white line had been drawn across the road and rumours circulated that mounted police would use tear gas. Amongst the groups, there were a lot of women, many taking political action for the first time. Most had rarely left the areas around their homes, and remained veiled in the presence of men, and now they were willing to march and confront police. There had been a long history of police repression against peaceful demonstrations, and given the magnitude of this march, there was a lot of anxiety. Both woman and Advasis were perceived to be at the margins of the social framework, so their willingness to put their bodies on the line was extraordinary.

When I showed a rough cut of the film in 1994 to a visiting professor from Beijing he said something that spoke to the very core of the movement. What struck him was how deeply felt and engrained the democratic ideal was in people. He saw this as the biggest difference between the populations of India and China. In India, people were aware of their democratic rights, and were willing to exercise and even demand them. The Indian state, despite its many shortcomings, has been successful at imparting these values.

My crew and I decided to see what kind of preparations were being made on the other side. When we got to the border, it was like a scene out of a B-movie. We were ambushed, drums were rolled in front of the car, and we were instantly surrounded by belligerent cops. I turned to my sound recordist, a wonderfully sweet guy who insisted on wearing a three-piece suit and tie all the time, and said, “You look like a producer, why don’t you go to talk to them?” Our story was that we were free lancers for Indian national TV. Given the poor state of communications we thought they’d never be able to check the story out in this fairly remote location. He returned distressed and assured me that we were going to be arrested. We were hauled up in front of the top brass of the Gujerati police who said throw them in the lock up. I stepped forward and started talking in Hindi, dropping names of various real and fictitious officials I knew in Delhi, trying to use class advantage. We were finally released, but it served as a warning. They had arrested senior journalists at other police check posts. At that time, the state of Indian press was still quite vibrant, those reporters had filed serious complaints with the press council of India so the police were forced to back off.

I think the fact that I stayed in spite of this intimidation helped me gain the trust of everyone in the march, it was a break through moment. I didn’t talk about it, but word spread, and people would laugh when they saw me and say, “Now you’re one of us, now you know what the cops are like. This is what we face every day.” Later, when we were attacked at night, people protected me. People would hide tapes for me. While marching people would be chanting slogans all the time, and often these slogans would turn into something playful and funny. “Whose forests and lands are these?” The response was: “They’re ours. They’re ours.” They would tease me for running up and down the length of the march shooting. Sometimes someone would call out, “Whose filmmaker is that?” And the response would ring out, “He’s ours. He’s ours.”

We were at the border impasse for four weeks, and because I had a car, and communication was so important, I became the go-between for the international NGOs. One of the key contacts in the US working with the environmental defense fund in Washington was an activist named Lori Udall. Lori had been with me on that trip during the fall when I’d gone to the valley for the first time, so I’d got to know her very well. Lori would brief me on what was happening, and I would meet the committee at the camp and give them the news. It looked like the World Bank was going to suggest an independent review of the project. Who should be on the panel? During the course of Shooting Indians, I had read through the Berger report on the Mackenzie Valley pipeline and forwarded his name. Lori was thrilled, and when the review happened, Tom Berger was second in command. The review asserted that the World Bank should step back. It was an unprecedented breakthrough, first of all that the World Bank allowed an independent review, and secondly that it agreed with the movement that there were serious flaws in the planning and implementing of the project, and that the settlement process was fundamentally flawed. As a result the World Bank withdrew their Dam funding.

I had never experienced a non-violent action, and two things became clear to me. First of all, non-violent political action was political theatre, and once you recognized it had to be theatrical, it needed to be witnessed, it had to have an audience. This audience had to be called upon not only to witness, but as a consequence of the unfolding drama, it should be moved and compelled to demand that the protesters’ needs be met. I became acutely aware of Ghandhi’s understanding of the role of media in whatever he did — his deep understanding of visual media, newsreels, photographers. Everything that he staged had an epic, visual feel to it. On the other hand, in this remote place, with no reporters coming from the state-controlled media, with marginal support from the press, which quickly died out once there was a deadlock, I became aware that non-violent stands on their own, without an audience, could be futile. There could be personal stands, but without witnesses they could not have a larger political impact.

This movement was asking some very profound questions. We all grew up in Nehruvian, socialist India under this common ideal: that someone has to sacrifice for the greater common good. But that someone was never the speaker, it was always someone else. The second question the movement asked was: development for whom? And at whose cost? These two questions still remain unanswered to this day. India is going as far as it can to keep from answering these questions. In the eastern side of what’s known as the tribal belt, we now have a significant armed insurgency which is described as “the greatest internal threat to the Indian state.” It’s being driven by large scale mining which is displacing people, and is being organized by a Maoist movement which has been working with the Adavasis. They have seen huge actions like those by the Narmada Bachao Andolan (Save Narmada Movement) that ultimately failed to stop the dam, or the displacement of people. Non-violent action has been unable to transform the course of development which has become even more ruthless in a globalized India.

Mike: Continuous Journey (87 minutes 2004) is an epic voyage of filmmaking that took eight years to make. Can you take us back there?

Ali: In the spring of 1996, the Canadian Navy was put on alert off the east coast of Canada. The RCMP had received a tip that a ship with 90 South Asians was heading towards Nova Scotia. The ship failed to materialize, but the event, of course, made headlines across the country. The papers were filled with the same old tropes of immigration queue-jumpers and the need to overhaul the immigration system. I find moments like these deeply disturbing and alienating, and decided that the best way to deal with this was to finally take up the challenge to make a film about the Komagata Maru. Few South Asians in Canada knew about what happened, even fewer understood the story in detail. This is the main reason why I pushed ahead.

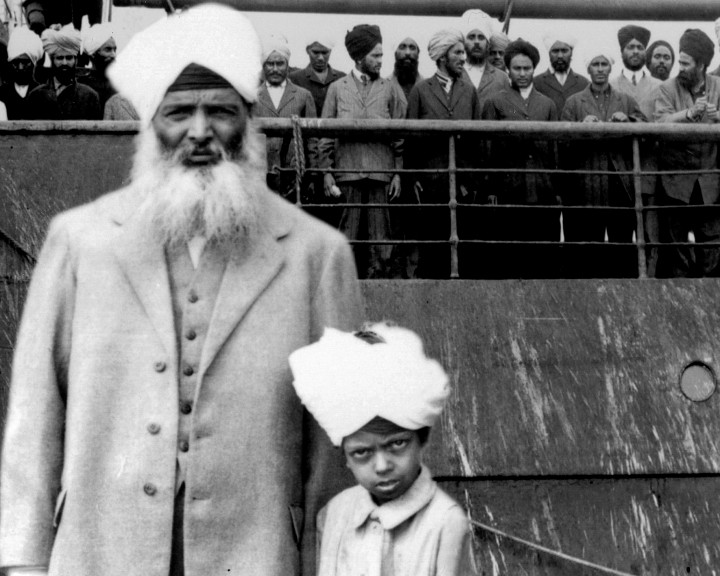

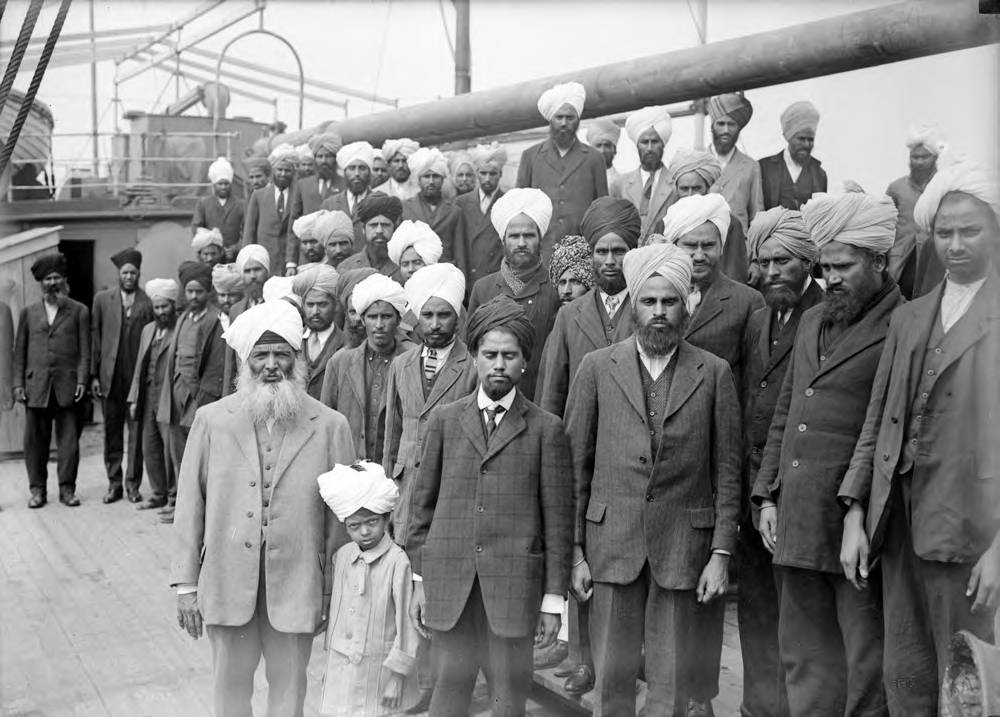

In 1914, Gurdit Singh, a Sikh entrepreneur based in Singapore, chartered a Japanese ship, the Komagata Maru, to carry Indian immigrants to Canada. On May 23, 1914, the ship arrived in Vancouver Harbour with 376 passengers aboard: 340 Sikhs; 24 Muslims and 12 Hindus. Many of the men on-board were veterans of the British Indian Army and believed that it was their right as British subjects to settle anywhere in the Empire they had fought to defend and expand. They were wrong.

During their two-month detention in the harbour, Canadian authorities drove the passengers to the brink of starvation. The stand-off was broken with the intervention of Prime Minister Robert Borden, who also called in a Canadian battleship to underline his stance. On 21 July, over 200 fully armed local militia lined the shore, while The Rainbow prepared for confrontation on the sea. All of Vancouver came out for the spectacle. Major confrontation was averted through eleventh-hour negotiations, and in the end, provisions for the Komagata Maru’s return journey were provided.

The consequences of the incident were dire: informants within the community were murdered, and a key player for the Empire was assassinated. Upon its return to India, the Komagata Maru encountered hostile British authorities who fired on the passengers, suspecting them to be seditious. Over 40 people went missing or were killed. Some of the passengers escaped, including Gurdit Singh, who lived to tell the “true story.”

Many people warned that I had taken on the impossible; it was a very complex story and there was minimal visual material about the events. What remained unsaid was that there was still considerable resistance to examining some of the so-called “darker chapters” of Canadian history. Independent documentary production in Canada is driven by broadcast television. The prize for all filmmakers is the increasingly rare broadcast license: a commitment from a Canadian broadcaster that ensures a national prime-time broadcast along with a fee that meets a minimum threshold. One broadcaster, one of the few who knew about the historic events, advised me, “Do us a favour – blame it on the British.” I looked for a glimmer of irony, but there was none. In casual conversation with another broadcaster he offered me pragmatic advice: “History on television is watched mostly by men in their mid-thirties to the mid-fifties. These are white men. So push the race stuff to the side and pump up the cloak-and-dagger intrigue. You should get some interest.” Another funding body suggested that I examine how the roots of “violence in the Sikh community can be traced back to the events surrounding the Komagata Maru.”

In the eight years it took to piece the film together I spent a lot of time in the National Archives looking at documents, photographs and film footage. I came across repeated references to notions of a “white Canada” in official documents and newspaper articles. At the same time I was struck by the almost complete absence of people of Asian and African descent in photographs and films. The links between their absence and the presence of white Canadians were becoming more insistent – yet there was no acknowledgement in the popular history of Canada that it had such a policy.

The events of July 23, 1914, were far too dramatic to remain unfilmed, even though film technology was barely two decades old. A Canadian warship was brought alongside the Komagata Maru. Hundreds of militia were ready on shore with fixed bayonets. Tens of thousands of people from shore watched the drama unfold. Archivists all around the world told me that the footage simply did not exist, that it either had been destroyed or lost.

I had been given some archival film footage on early Chinese immigration to Canada by friend and colleague Richard Fung. Richard had ordered some material from the National Archives in the mid-nineties for his film Dirty Laundry. I had the Betacam tapes sitting at home for many years. I finally had them transferred to VHS and was scanning them while I spoke with someone on the phone. I started seeing shots of soldiers in kilts with fixed bayonets marching through residential streets. The reel was catalogued as the Governor General’s visit to Victoria. I recognized the streets of Vancouver. I quickly got off the phone. This could not be. Surely these were not the Seaforth Highlanders? The only time they had marched through Vancouver was on July 21, 1914, when they had been called to intimidate the passengers of the Komagata Maru. The next shot showed boats of all sizes in a very crowded Vancouver harbour. My mouth went dry. The next shot was a brief jerky pan of the Komagata Maru and its Indian passengers – one of the very few turning points in early twentieth-century Canadian history to be documented on film. After nearly 90 years I was the first person to recognize this mislabelled footage – there was no turning back now. I sat and wept.

One segment of the film that shocks almost everyone is what my film editor Graeme Ball dubbed “the White Canada sequence.” We edited together a set of shots from early twentieth-century Vancouver amateur movies of family and social events. I had come across a song called “White Canada Forever” in Ted Ferguson’s book A White Man’s Country (1975). “White Canada Forever” was a beer parlour ditty that had become an anthem of sorts for the Asiatic Exclusion League. During the anti-Asiatic riots of 1907, a mob led by the League went through the Japanese and Chinese quarters of Vancouver singing the song and smashing property and businesses. According to some reports, “White Canada Forever” enjoyed an revival while the Komagata Maru was in the harbour.

The Komagata Maru’s voyage and its aftermath exposed the Empire’s myths of equality, fair-play and British justice, and became a turning point in the freedom struggle in India. This is a story that helps ground the South Asian presence in Canada today. I believe it is because of the efforts waged a century ago by people who came from South Asia that we are all here now. These struggles for justice and equity are far from over, but this process makes Canada a better place for everyone.

Mike: Passage from India (22 minutes, 1997), finds you digging into the roots of the Indian community here in Canada via the family chronicles of Bagga Singh. Your film is both intimate and international, and shows how individuals have helped to push against racist laws and norms. Can you talk about the trip of making this movie?

Ali: Since moving to Canada from India in 1983, I had wanted to learn more about the origins of the Indian community. Most of the people that I met at University were second-generation Canadians whose parents had come from India in the mid-60s and early 70s. I knew there had been an earlier wave of immigration, mainly to British Columbia, though most Canadians knew little about it.

Over the years I worked on several films dealing with immigrant issues and this early history kept re-emerging. In 1986, the Air India crash which claimed the lives of over 300 Canadians of Indian origin, threw a harsh spotlight on the Indian community in Canada, and specifically the Sikh community in British Columbia. The militant Sikh nationalist movement in the state of Punjab in India received some support from the community in Canada. The Air India bombing was suspected to be part of that struggle. Two years earlier, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her Sikh bodyguards in retaliation for the Indian Army’s attack on the holiest Sikh shrine, The Golden Temple. In the 80s, it seemed that the Sikh community was always in the spotlight.

However for me, this was not just Sikh history, it was part of my history as a person from India. The earliest Indian immigrants to Canada were largely Sikh, but they considered themselves Indians and played a critical role in the struggle for Indian independence. Without their ground-breaking struggle, it would have been impossible for me to immigrate to Canada. When the opportunity came to do Passage From India, it provided an opportunity to seek out some of the early families whose ancestors had settled British Columbia. I was joined by researcher/writer Nisha Pahuja. Nisha’s parents came to Canada from India in 1971, when Nisha was two, so her collaboration introduced another layer of understanding.

As Nisha spent hours on the phone, which she unabashedly loves to do, remarkable stories began to emerge, not just from Vancouver, but all over British Columbia. Prem Gill, in Vancouver, did additional research and played a crucial role in seeking out additional people. In October, I came west to attend the Vancouver International Film Festival with my film Shooting Indians: A Journey with Jeffrey Thomas. This trip gave me an opportunity to meet people who would potentially be the subjects for the film. Most of the old-timers from the first generation had passed away. However, their children were still around.

The meaning of the old phrase, “You have to know where you come from to know where you are going” soon struck home. Many families knew very little of their own history. In some cases the impact on kids who were third-generation was painful — they didn’t see themselves reflected in Canadian history books, their parents knew little of their own family history, and had passed little on to them. At other times there was a recognition of the history, but no interest, some saw themselves as simply Canadians. They were fully assimilated, yet the notion of the extended family was still extremely strong. In some families I felt a degree of awkwardness when they discussed the rural and working class roots of the first generation.

Everywhere I went there was tremendous generosity and openness. Some people like Kam Power of Abbotsford, driven by our interest, did some of her own research on her grandfather by going to the local archives, and gained some insights into her family history. Over three generations the community had done well for itself in spite of the pervasive racist policies of the government. Most families lived in large suburban homes and worked as professionals in a wide range of fields. Some were now the owners of saw mills their ancestors had worked in as wage labourers. A few had become economically and politically influential in British Columbia.

After a long search, I met Belle Puri a well known CBC Vancouver reporter who had become a producer. I was struck by her knowledge of her family history and her understanding of it, even though her maternal grandfather, Bagga Singh, had died before she was born. I felt Belle had a very clear sense of herself as a British Columbian whose roots were quite deeply integrated in history. Being a media personality, Belle was not at all daunted about being in front of the camera.

I returned to Toronto, feeling quite thrilled, but I still wanted to get stories about personal incidents that would give a sense of what it was like for people before 1947. The film would be woven from three strands: the history of immigration from India and the challenges faced by the first immigrants in Canada; a personal history of the community through anecdotes of second generation people; and the main spine of the story would be Belle’s family — an ambitious plan for less than 24 minutes of finished film.

In between interviews with Belle, we went on a road trip first to Kamloops, in the British Columbia interior, for an interview with Gurbachan Heed who had lived there since she came in 1932. As is the norm in South Asian homes, she laid out a fairly elaborate tea for us, with samosas, Indian sweets and savouries. Gurbachn Heed lives on Singh Street, named after the family farm which at one time ran the entire length of the road and was perhaps the only street in Canada to have a Punjabi name. Now she has 100 acres of apple orchards. In the background new condominium developments loom above the apple trees. She spoke of the interaction between the Sikh community and the Japanese and Chinese workers they would sometimes hire on the farm, and the setting up of the local Sikh gurdwara.

On Vancouver Island the first stop was Duncan, and an interview with Karm Singh Manak. Nisha had warned me that Karm is very particular about his bridge games every night, so we only had an hour. The entire extended family was there. Tea, cookies and samosas were served. Karam Sing Manak spoke at length about the struggles at the saw-mills and the fight to get a franchise for Indians. At the same time, he talked about his non-Indian friends and the support he got from them.

We stayed in Duncan for the night and drove towards Victoria the next morning, but first we made a small detour towards the small logging town of Lake Cowachin. We were all beginning to feel that this road trip was a pilgrimage to the roots of the community. It came as a pleasant surprise to see the presence of Sikh workers acknowledged in the small museum of this town. The museum director gave us directions to Paldi, which we had missed on the way to Lake Cowachin. Paldi was the only town named after a village in India and was settled by Indians.

On the way back to the main highway we looked carefully for the dirt road leading to Paldi. This time we got the turnoff and there it was. A small gathering of neatly kept houses, and a fairly large Gurdwara. Mayo Mills which bore the owner Mayo Singh’s name is long gone, as are the bunkhouses that housed the workers. As we walked around the deserted streets, the rain clouds parted and a perfect rainbow appeared. In its heyday, Paldi was a multicultural mix of Chinese, Japanese and Sikh workers. It is still inhabited by eighteen families.

We arrived in Victoria soon after five, and prepared for our last interview with Kuldeep Bains, who came to Canada as a young man in 1954. His father had preceded him and had lived in Canada since the twenties. Kuldeep Bains is the owner of a large travel company. A distinguished man in his late sixties he leads a vigorous life, spending part of his time in Victoria in a modest bachelor apartment with a spectacular view of the Harbour. Even he had tea and Indian sweets for us.

Our final interview was with Nick Mohammed, who even in his seventies is an impeccably handsome man with a physique of a forty year old. Nick’s father came to Vancouver in 1905. He was one of the few Muslims who came from the Punjab at the turn of the century. Nick joined him as a young man in the late thirties. He worked in the saw mills as well, and visited the gurdwara often, for social visits. The Sikh community was supportive of all peoples from the Indian subcontinent. Nick was soon spotted by a school coach as a natural athlete and was encouraged to take up wrestling. He was the national champion, and then became the first person of Indian origin to represent Canada at the 1956 Olympics. He just missed getting a medal, placing fourth.

What struck us all in these interviews that in spite of the openly racist laws of the period, none of these old timers harboured any bitterness. They spoke passionately about Canada and were able to separate government policies from their interactions with ordinary Canadians. At times they even laughed at the indignities they and their parents had to suffer, but they refused to be victims. They used the law to fight back and were quietly supported by many white Canadians around them. Jack Uppal was the only one willing to talk about racism. His father, Dalip Singh Uppal, had been on the Shore Committee that was mobilized when the Koagata Maru arrived. Jack appears in Continuous Journey as well. After all these wonderful interviews with people, the task of choosing which moments to use in whittling it all down into one sliver of a documentary was quite a challenge in post-production.

It is vital for each of us to know our histories, even on a personal level, and this was brought home for me again only a few years ago. I had chanced across manuscripts of short stories written by my father. He was a frustrated artist, unhappy as an executive, but I did not know that my father wanted to be a writer. Along with these stories were rejection letters from several magazines. I had no idea that my father wanted to be a writer. The stories were fictional, if clearly autobiographical, but a bigger surprise lay in store. One of the stories was written in the first person and the main character, a young man, dreams of going to Bombay to be a filmmaker. I had no idea that my father secretly dreamed of being a filmmaker; it came as a huge shock and surprise. My father had actually gone to Bombay for a couple of years, hoping to engage in the Bombay film industry. I think he liked working at Kodak so he could live vicariously through a whole range of filmmakers, I have photographs of him with directors like Polanski and Satyajit Ray. So in spite what I have told you, perhaps there was some small piece of genetic memory that pushed me in this direction, and that would only be revealed to me when I started calling myself a filmmaker. Living a dream that began within my father.