Fallen Flags: an interview with Amanda Dawn Christie (2010)

Mike: Can you tell me about Helen Hill?

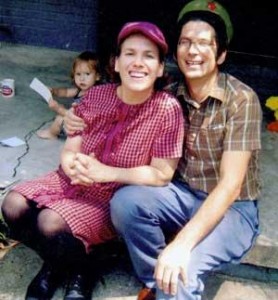

Amanda: I met Helen Hill shortly after moving to the big city (Halifax is the big city for anyone growing up in the Maritimes). I had moved there to work for the Nova Scotia Arts Council during the brief period when they actually had one. It was in the fall of 1999 and I didn’t know many people there yet, but since I was working as the receptionist I got to meet local artists whenever they would come in to drop off grant applications or talk to program officers. One day, a very energetic girl walked in. I say girl because I was sure she couldn’t have been more than 14 years old, when in fact she was actually in her late 20s, seven years older than me. She wore a colourful toque over her pigtails, had mittens dangling from strings out of her sleeves, and seemed barely able to contain the energy that was building inside her. She spoke with a quick, breathy energy, as if the words were too good to hold inside and had to be shared as quickly as possible. She had come in to speak with Peter Kirby (one of the program officers), and to drop off a handmade thank you card for a grant that she had received. Not many artists ever came in to drop off thank you notes or to say thanks in person. We had a lot of people calling and writing letters to complain and criticize the arts council when they didn’t get grants, but not so much feedback when they were successful; so this thank you note and visit from Helen was refreshing.

After her meeting with Peter, she stopped to talk with me on her way out the door. She introduced herself and told me that she and her friend Becka Barker were organizing a festival. I can still hear her extending the invitation, the sentences short and to the point, quick, eager and full of breath. “We’re having a Scrappy Film Festival tonight! And you should come!” I asked, “What’s a Scrappy Film Festival?” She replied with the same rush of energy. “We’re setting up a 16mm and super-8 projector in the parking lot behind the general store on Gottingen Street and we’re going to show some films. If you come early, we have clear leader and sharpies so you can make your own film right there on the spot and we’ll project it for you! Or if you have your own film, you can bring it and we’ll project it!” She handed me a little photocopied flyer for the Scrappy Film Festival, and said, “Hope to see you there!” After she left, I sat for a while with that feeling you have after a very intense encounter, when the other person has left a bit of their energy behind with you, beating in your chest. She was one of the first people I met in Halifax, and unlike many of the other clients at the Arts Council, she had made an effort to talk to me as a person and to invite me out to an event. I was also a bit confused because she was so energetic that I wasn’t sure if it was actually sincere or not. How could someone be so intensely positive?

That night, after work, I found my way to the Scrappy Film Festival. It was a crisp and cool but not too chilly fall evening, and as I walked alone I wasn’t sure if I would be able to find it, given that I still felt a bit lost and overwhelmed in the city. But sure enough, there, in a parking lot after dark, was a crowd of people sitting around drawing on bits of clear 16mm film leader. I didn’t arrive in time to draw on film, but I had brought a super 8 film with me. A few months before moving to Halifax, I had found my parent’s old super 8 camera in their basement, along with two old cartridges of film. Inspired by the Acadie Underground super 8 screenings that I had seen at the FICFA (Festival International de Cinéma Francophone en Acadie) in Moncton the year before, I had taken up my parent’s camera and shot my first two rolls of super 8 film in the summer of 1999. I sent the cartridges away to be processed, but never had a way to view them. It was a film that I shot while driving with my younger brother — the stock had aged, and the colour shifted to a bleached-out green and yellow. Other people projected their own super 8 and 16mm films as well. They also projected some Norman McLaren film prints, and the evening ended with a projection of all of the handmade animations that had been made on the spot with the sharpies and clear leader. By the end of the night, any doubts that I had about Helen’s sincerity were wiped away; it became obvious every ounce of her positive energy was actually genuine.

After that night, both Helen and her husband Paul became very positive forces for me. Whenever I felt lost or overwhelmed in the city, just running into Helen or Paul would cheer me up and fill me with an intense surge of optimism and hope. Around that time I joined the Atlantic Filmmakers Cooperative and began to make other friends in that community.

In the winter of that year, Helen came into the Arts Council and told me about a project that she was organizing called a Ladies Film Bee. She was inviting women to shoot a super-8 film, hand process it, and then get together to animate and manipulate the films like at a sewing or quilting bee. At first I declined because I wasn’t a real filmmaker and felt that she should ask someone more qualified. “Don’t be silly! Of course you’re a filmmaker!” she said. So I agreed and signed up. 12 women were involved and we each shot black and white super-8 film, and processed it in her bathtub. While I had worked in darkrooms with stills photography before, I had never processed motion picture film. She had blocked out the window light using wool blankets and garbage bags. I sat on the floor between the toilet and the bathtub, processing my film nervously in the dark, as she called instructions from the other side of the door. After the chemical process, while my film was washing, I sat and drank tea with her in the kitchen and played with her pet pig. That night I walked home with a grocery bag full of tangled super-8 film that I later hung to dry in my shower once I got home.

Two weeks later, the Film Bee itself took place in Lulu Keating’s kitchen on Brunswick Street. We all sat around the table drinking tea and eating cucumber sandwiches with the crusts cut off for a fun afternoon of chit chat and film animation. There were sharpies and needles, and nail polish, and dyes and bleach, and we sat around the table casually talking as we scratched away and drew on our films frame by frame. I made two super 8 films at the Film Bee: Here (3 minutes 2000) and Dishes (3 minutes 2000).

The Ladies Film Bee took place around the same time that Helen was working on the Recipes for Disaster book. She had asked me to contribute something, but again my insecurities got the best of me and I declined, saying that I wasn’t a real filmmaker and couldn’t possibly have anything worth contributing that anyone would want to read. I still regret not overcoming those insecurities and contributing something. She took the films that we made at the Ladies Film Bee and screened them in Toronto at the Splice This! Super-8 film festival when she launched the book.

I actually consider those to be my first films, as those were the ones that really got me started working with handmade processes. Without Helen Hill’s initiatives and encouragement, I never would have become a filmmaker. I began working in 16mm, always hand processing and working with experimental approaches. For the rest of my time in Halifax, Helen and Paul were a source of inspiration and encouragement for me. Their positive energy was as important as any technical workshops that I had taken.

Mike: Can you talk about what happened to Helen?

Amanda: I was working on an film in Vancouver the morning that Helen was killed; although I didn’t know about her death until that night. It was an inexplicably strange morning, and it is eerie to revisit that memory. For most of the previous month, I had been working on a series of ultra short 35mm films for the Rotterdam International Film Festival. They had a program that year called “Wait A Second” in which they commissioned filmmakers from around the world to make short motion picture films using rolls of 35mm still photography film. 24 frames of stills film equals 48 frames of motion picture film, so each of these films was only about 2 seconds long. I had already made a few, but that particular morning I decided to work with a roll of colour infrared film that was sitting in my fridge. Knowing that infrared film would have an interesting response to plants and to human flesh, I decided that I wanted to film either vegetation or animals. It was a sunny morning, but there was a heaviness in the air that I couldn’t explain. I looked around my apartment for some plants to film, and noticed that the bouquet of flowers on my dresser was dead, and yet somehow incredibly beautiful because of the way that the sunlight was streaming in and around the withered leaves, crisp petals, and dry stems.

The camera set up I had for filming half frames was such that I would photograph one thing with half the frame covered, then rotate the camera on the tripod head 180 degrees to face the exact opposite direction, and cover the other half of the frame, then advance the film, return the camera to the original starting position and start over. Knowing that this would create a flicker effect, I chose my compositions such that the placement of objects in the frame was nearly identical in terms of colour and shape — only the actual content would differ and flutter in projection. For this film, I aimed the camera at the bouquet of flowers on my dresser. It was a black dresser with a window behind it, and I framed the horizon line of the dresser in the lower third with the dead flowers in the right third. For the alternating frame, I aimed the camera at my bed which had a dark coloured duvet, and I placed the horizon line of the dark bed in the lower third with a white wall behind it. I laid on the bed, and looked at the camera despondently; despite the incredible sunlight that morning, there was a heavy melancholy that I could not explain. Laying on the bed and looking down the barrel of the lens of the camera, I was filled with a sense of confused sadness and a heavy loss of motivation that I could not explain. The film flickered between the dead flowers and myself laying motionless, questioning the camera. After shooting the film, I had trouble finding the impulse to do much of anything else the rest of the day.

That night, I went downtown to drop the roll of film off to be processed. It was dark because the sun was setting early in the cold months. I was walking down Seymour Street when my cell phone rang, it was my friend Ben Donoghue. There was no small talk or pleasantries as he immediately asked, “Amanda, have you checked your email today?” I replied with a bit of confusion, “No, why?” He continued on cryptically to explain that people were talking about something on the Frameworks internet forum, which he knew that I subscribed to, and he didn’t want me to find out that way. “To find out what?” I asked. “Helen’s been shot.” “Oh my God, is she okay? Is she in a hospital? How bad is it?” The thought that the shot might be fatal was not a possibility. It never occurred to me that this was what Ben was calling to tell me. At worst I thought that she would have a long recovery period in a hospital or rehab. “No Amanda, she’s not alright. She’s dead. She was shot in the neck while begging the shooter not to hurt her baby.” I stopped where I stood in shock and disbelief. I had difficulty grasping what had happened and couldn’t form sentences. I felt the air expel from my lungs and a coldness grip my chest. I desperately wanted to know everything, the where, when, why… and yet simultaneously I did not want to know any of it because that would mean admitting that it was true. The whole thing was too unbelievable.

Ben explained that someone had broken into her house in New Orleans at 5 am. She went to the door, and her husband Paul had grabbed baby Francis and ran to the bathroom. While she was begging the man not to hurt her baby, he shot her in the neck, then shot Paul several times in the arm as he ran to the bathroom. Paul survived and Francis was physically unharmed. The police found Paul holding Francis and sitting next to Helen in a pool of her blood. The story was horrific and unbelievable. How could this happen to people who were so kind, loving, and full of life and charity? Of all the people that this could happen to, the fact that it was Helen and Paul made it so much more unbearable.

In terms of the film that I had made that morning, it came to a strange and eerie end. I made eight of those ultra short films and sent them to Rotterdam. In total, various filmmakers had contributed 41 ultra shorts to the “Wait a Second” program. The Festival spliced one on to the beginning of each feature film in the “Sturm und Drang” program. I had a travel grant from the Canada Council to go to Amsterdam to attend the Starting from Scratch Film Festival which took place two weeks after the Rotterdam Film Festival. I was still feeling shell shocked as Helen’s death occurred barely a month ago. I had begun to question my world view and my life direction in general. I was in the process of finishing my Master of Fine Arts degree at Simon Fraser University, and all of a sudden this art making felt incredibly self indulgent. Why bother? What was the point of anything?

I travelled to Amsterdam for the Starting from Scratch festival in February, and there I met Pim Zwier, the programmer who had curated my work and invited me to make the ultra-short films, and who would later become my lover. A few months after the festival, I finished my MFA and moved from Vancouver to Amsterdam to live with Pim. That is a whole other story and chapter in my life, and yet it is inextricably linked to this story, for I can’t think of one without being reminded of the other. During the festival, I was staying at Pim’s house along with two other artists when all of the ultra-shorts came back from the Rotterdam Film Festival and we spent an evening cutting off the leader and splicing them together so that they could screen all at once during the Starting from Scratch festival. All 41 films would only take 6 minutes. It was not until we had spliced them all together that I realized that January 4, I lay down, was missing. The infrared film of the dead flowers and my laying on the bed; the one that I had made the morning Helen was shot; the one that I had in my coat pocket when Ben called to give me the news. I like to believe that perhaps that film is still spliced onto the head of a feature film, traveling around the world and confusing projectionists. There is a good chance that someone cut it off and threw it away; but there is also a chance that it has been overlooked and that it is still spliced on to some film as a mysterious remnant, lingering, and waiting for the light.

Mike: I know that every little girl longs to turn into a horse or a ballerina, but the punishing disciplines and hand-me-down forms of ballet are a mystery to me. Who would want that? Not to mention spending your life in front of mirrors which reflect an ever changing body. It seems a breeding ground for self hatred and body issues. Can you talk about your life as a dancer?

Amanda: It’s funny that you should mention horses as well as dance. As I child, my family actually had horses and I have many fond memories of riding ponies bareback in the hay fields behind our house. But we had to get rid of the horses when I was 9 because of my allergies.

As a child I wanted to do and to be everything, all at the same time. I wanted to be dancer and a scientist and an astronaut and a paleontologist and a firefighter and a musician and a writer and a veterinarian. I somehow had the idea that when I grew up I could be all of them at once. However, by the age of 11, I had set my goal firmly on dance, and only dance – everything else (the science team, writing, music, etc) were just hobbies. I was obsessed with movement and locomotion. I lived for the sensation of speed when riding horseback, the dizzying sensation of spinning in circles, the power of my own body to propel itself in play; running, jumping, rolling, and climbing up trees.

From as far back as I can remember, I was consumed with an awareness and interest in the limits between my body and the rest of the world, as well as between my body and my “self,” whatever that was. Even before I was old enough for school, I remember laying in the hayfield behind the house looking up at the sky with my hand extended and feeling anxiety over the fact that there was a place where I ended (the limits of my outstretched fingers and the surface of my skin) and the rest of world began. I felt contained and constrained within this physical body, and yet I also felt separate from it at the same time. I had seen people missing limbs (my grandfather was missing some fingers and a great uncle was missing a leg), so I knew that “I” was not my fingers or my hands or my legs. I would lay in the field drawing imaginary lines across my arms and legs imagining that they were cut off and realizing that if I cut my hand off, I would still be me. I was always searching for that line within my physical body where I ended and the body began. So I guess that you could say that a contentious relationship with my own body began long before entering the realm of mirrors.

My formal dance training began a little late by classical standards: I started at 10 years old rather than 4. Before taking dance classes, I had already done gymnastics and figure skating, so I was well versed in moving the body in unnatural ways and positions. This is essentially what a lot of classical dance, gymnastics, and figure skating does. They impose geometrical shapes onto the human body — the positions are rigid and geometrical, rather than soft, fleshy and flowing; prioritizing shape over motion. This is ironic since dance is about motion, but in many classical forms, movement is used only to connect one shape to another; the movement is merely a link rather than the substance itself. This emphasis on shapes made by the body bleeds into shapes of the body. Classical dance is not only interested in making shapes, but also in owning shapes — owning a body that fits the desired shape of the time (and the desired dancer body has changed throughout the years, along with the fashions).

Mirrors are the ultimate tools in creating these shapes. They place an emphasis on the visual over the more subtle and liminal senses. This is a shame because dance can be so much more about the bodily senses of touch, locomotion, balance, kinesthesis, and proprioception. But this emphasis on the visual sense creates a very real obstacle for many dancers as they focus on the isolated sense of sight; looking and comparing and trying to emulate the shapes of others to the point that they lose the physical connection with their own body. They no longer feel the dance, but watch it from outside of their body. They use the mirror to catapult their brain out into the imaginary audience and imagine what their body would look like on stage, rather than feeling it in the present moment.

There was a certain severity in being surrounded by mirrors and bodies in tights for the entirety of my adolescence. The tights worn in dance classes hide nothing and every stage of puberty is thus carefully analyzed and compared with other bodies in the class. I don’t know what it would have been like to go through puberty with fewer mirrors and wearing regular street clothes, or “civies” as one my dance instructors liked to call them, as if our tights were a form of military attire. I spent so much time in dance studios, that even when I was wearing regular street clothes I could not see myself objectively – I always had that image of myself in tights burned into the mirrors of my mind. I might look alright in jeans and a sweater, but what I saw in my mind was the overly analyzed images of the shapes made by my body in tights and mirrors.

I was actually quite underweight before puberty due to a digestive illness. But once puberty hit, I grew into an inherited, reproductive build that was apparently better suited for babies than ballet. Breasts, hips, and thighs are an abomination in the classical dance studio, and I recall so much energy expended trying to constrain and control them.

At the age of 14, I was weighed by the artistic director of one company and told that I would not be allowed on stage until I lost 20 pounds. From that point onward I was asked to write down what I ate and was weighed every week to ensure that progress was being made. Even at 14, I knew that this was problematic because I felt that I was intellectually above falling prey to the beauty myth. Thus began a mental cycle that would haunt me for years. There was an initial sense of inadequacy, of having an “ugly” body – of not owning the desired shape. This would be followed by the awareness that I shouldn’t care what my body looked like, because I felt that I was above falling for societal pressures. I felt bad about feeling bad. There was hatred of the body followed by hatred of the intellect for allowing myself to hate the body. I tried to ignore or repress those thoughts, but it was a losing battle. Not dancing wasn’t an option, for I was happiest when using my body in space — choreographing, rehearsing, and performing. So at 15 I switched to a different dance company that was much more accepting of various body types, but the cycle had already begun and the mirrored rooms only propelled it further.

During my undergrad I discovered performance art. It used the body but didn’t seem to have all of the hang-ups of classical dance. I continued working with my body from 1995-2004, naming what I did “performance art” instead of dance. I felt that I didn’t have the body to be a dancer, so I called it performance art – but what I was doing was just dance by a different name. While in Halifax, I discovered contact improvisation and began regularly taking contact workshops and attending jams organized by the North End Dance Co-op. I also discovered other forms of contemporary dance that were more about movement and less about shape. As a result, during my 5 years in Halifax, I presented several performances at dance venues and festivals, but I always referred to them generically as “performances” rather than “dances.”

When I arrived at Simon Fraser University in 2004 to begin my MFA, the dance department was incredibly welcoming and encouraging. When I once made the comment that I didn’t have the body to be a dancer, they laughed and said something to the effect of “that is so 1950s!” I began to pursue technique classes at SFU as well as with Edam Dance in downtown Vancouver. I took advantage of the vibrant dance scene in Vancouver and attended many performances where I saw an incredible variety of body shapes, sizes, and ages dancing; and dancing beautifully. I remember one in particular performed by a woman who would likely have been medically classified as obese, and yet it was one of the most incredible dances I had ever seen – because she knew her body and moved well in it.

It was through this transition from classical to contemporary dance which happened gradually from 1999-2005, that I began to inhabit my body with acceptance rather than analysis. While at SFU, I spent a lot of time alone in the dance studios – not only to work on choreography, but also working through ideas for films and essays. I began to think with my body. The first thing I would do upon entering a studio would be to cover the mirrors with curtains and to turn out the lights. I would focus on feeling the experience of the movement in my body – relying on touch and locomotion, rather than sight. I would only uncover the mirrors at the last stages of refining or rehearsing a choreography – but even then I would often simply videotape myself and analyze the footage afterwards, rather than in real time.

When it came to working on films and essays, I would keep a note book with me in the dance studio at all times, and do improvisation exercises based on the ideas I was exploring (either in film or in text). I would jot down ideas, charts, and diagrams as they came to me. I would often try to replicate the movements of film machines (cameras, projectors, optical printers) with my body. I would also play with applying film language (jump cut, match cut, fade, dissolve) to dance choreography — to approach choreography as I might approach editing a film. I would then do the reverse when working on the optical printer and apply choreographic techniques (breath, direction, momentum, accent) to my films.

In all, I would have to say that the most important development in my life as a dancer was learning to inhabit and experience my bodily senses while dancing – to experience the dance from the inside rather than trying to see it from the outside. This lesson has carried into many other aspects of my art practice and my life in general.

Mike: When you were setting up the 16mm projector in Sackville’s Carriage Factory, you used one of your own films to test it out, in part because, as you said, if it gets scratched, it’s only your film, and not the ones being screened that night. It was a beautiful rainbow of a dance movie, and you were the solo performer. I know you like to work alone, but isn’t there also some sense of affirmation at work in the picture? Some sense of, “I am OK, and I am going to show just how OK I am?”

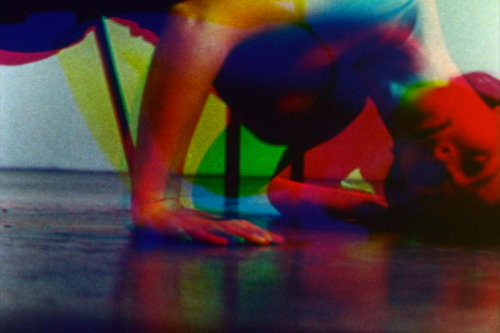

Amanda: 3part Harmony: Composition in RGB #1 (5.53 minutes 2006) is a film that began with an idea I had while working as a commercial photographer in Halifax, but that was actually brought to life and completed while living in Vancouver during my graduate studies.

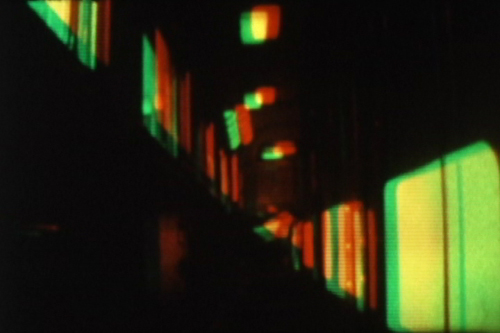

I was reading up on colour theory one day at the photo studio, and I immediately became fascinated with the technicolour process and the fact that light could be separated into its three primary colours (red, green, and blue) and recorded onto black and white film through filters and then recombined again into full colour. I was so enamoured with this concept that I wanted to try it out for myself, but it seemed a pointless endeavor given the ready availability of colour film and digital cameras. Why bother? So I began trying to think of a situation that would actually engage with that colour separation process on a conceptual level in a way that would take it beyond a mere technical exercise.

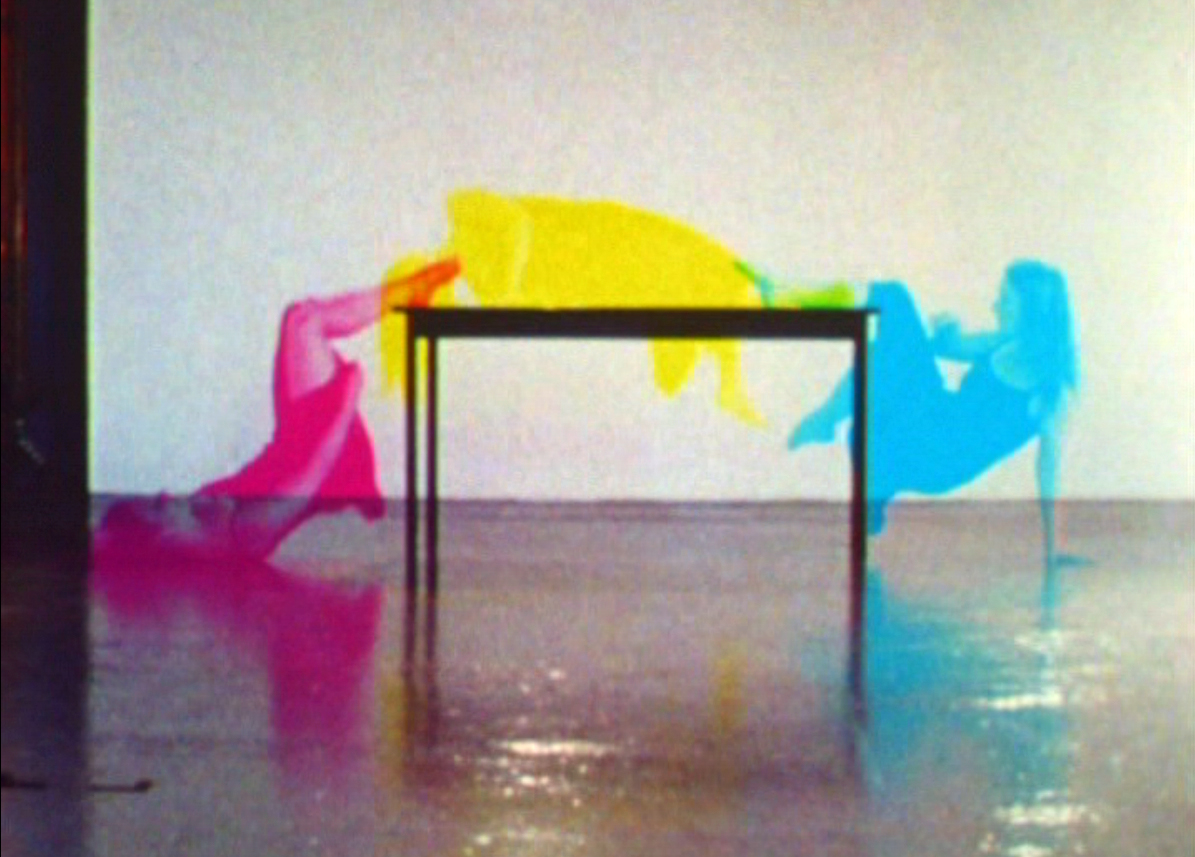

At that time, I was also working in the dance studio quite a bit, preparing choreographies for performances that I was presenting in Halifax. It occurred to me that a dance film might be an ideal way to play with this process. If the camera and the set stayed stationary during three separate passes of red, green, and blue, and if the only thing that differed in each pass was the position of the dancer’s body, then in the final recombination of the primary colours, the set would appear natural and in full colour, while the dancer would be able to separate into red, green, blue, cyan, magenta, and yellow — while only appearing in full natural colour when she was in the same place and position in each of the three passes.

I received a three-minute film grant from the Atlantic Filmmakers Cooperative. Successful applicants were given $3000 to make a 3 minute film. Shortly after receiving the award, I got into the MFA program at SFU, and moved to Vancouver. It was a pretty major transition, as I quit my job at the photo studio, left my ex-husband, and moved 6000 km from the Atlantic coast to the Pacific. This upheaval, departure, and transition would figure prominently in the development of the choreography and movement vocabulary of the dance.

So while the idea and the funding originated in Halifax, the bulk of the work and creative process happened in Vancouver during my time at SFU. One of the ironies of making this film was that I really hated most dance films that I had seen, and here I was about to make one of my own. So even though this film was an extra project above and beyond the MFA requirements, I decided to use it as a chance to figure out why I seemed to hate dance films. During the fall of 2004, I spent the semester watching as many dance films as I could get my hands on, integrating this into my course work, reading about dance on screen, and writing essays about it. I wanted to take the elements that I found most engaging and interweave them into the technical process of colour separation and experimental film.

Despite the fact that I had used my own body in earlier films, if I needed a human body as a compositional element in the frame, I was not planning on performing in this one. In this particular case, since it was an actual dance film, and given my previous hang-ups with my body, I was determined to set the dance on someone else. I would do the choreography, the filming, the processing, and the optical printing, but I would not be the performer on screen. One afternoon as I was discussing the project with Rob Kitsos, I was saying that I didn’t really have the body to be a dancer, and as such I was planning to set it on someone else who did. He replied that this was precisely why I should perform in the film — as a way to get over it. I was very uncomfortable with the idea of performing in the film at first, and that discomfort made me realize that he was right. This was something that I really had to do.

During the spring of 2005, I spent four months working in the dance studio almost every day on the choreography for this film. I was working on three separate but related solos: a red dance, a green dance, and a blue dance. I worked on developing a movement vocabulary specifically for my body. Rather than drawing from the tired lexicon of historical dance techniques and genres, I decided to play with pedestrian movements and reenactments. I played a lot with risk and looking for the line between control and loss of control. As a result, I got a lot of bruises during this stage of the project as I fell off that table over and over again, and it fell on me several times as well. When you watch that film, it looks like the table is nailed to the floor, but it’s not.

Also nested within those choreographies are three narratives, one for each colour. I’m sure that most viewers do not catch them when viewing the film, and I’m fine with that. They are actually very personal narratives that I used merely as a driving force while sourcing the movement vocabulary. The red choreography (which appears as mostly cyan in the film) had to do with sexuality and my sexual identity after leaving my ex-husband. The green choreography (which appears mostly as magenta), had to do with growth, birth, and new beginnings after the move from east to west. The blue choreography (which appears mostly as yellow) was the most intimate and has to do with death. While working on the choreography for this film, two people I had gone to school with died tragically back home in New Brunswick. I worked through my grief in the dance studio by reenacting the events that had lead to their deaths, as well as reenacting the events that could have saved their lives. The movements in the blue/yellow choreography are sourced from these reenactments. Interestingly, the yellow figure (blue choreography) is the faintest and most ghostlike of the three. So when you boil it down to its most basic forms, the three dances are about birth, sex, and death, expressed through pedestrian movements sourced from personal experience.

Mike: Is it strange or not when you note that dealing with death was more intimate than the changes in your body, your sexual identity, or leaving your husband? Perhaps this is all too much to get into in a public interview, but if you would care to share any of these details, it would only deepen the experience for the reader. Entirely up to you – no pressure at all.

Amanda: Perhaps “intimate” was the wrong word to use in that case. It was more that this was the one that hit me the hardest — and I’m not entirely sure why. Perhaps it was the unexpectedness of it all. The Red/Cyan choreography about my sexuality was also quite intimate, but in a different way. It was something that I had been living and working through over a long period of time. I was dealing with my sexual independence after extricating myself from a long-term relationship. The separation and divorce was difficult, but it was also predictable and ongoing. The deaths were shocking. I wasn’t particularly close with this couple, but I grew up in a rural area and went to a small school where everyone knew each other and shared in the growing up — for 9 years these people were part of my childhood and early adolescence, on the playground and in classrooms. It also hit me hard because I was so far away from New Brunswick, and this was my first long-distance grieving experience. It was January of 2005 and these two former schoolmates had been out driving one night in a snowstorm. It was a very bad storm and they had apparently pulled off to the side of the road to wait for better visibility. They left the van running to stay warm, but snow covered the exhaust pipe. As the fumes filled the van, they no doubt peacefully drifted to sleep, as they inadvertently poisoned themselves in an attempt to stay warm. The whole situation struck me much harder than I expected. I worked through the grief in the dance studio with movements of opening and closing doors, opening and closing windows, turning keys, and reenacting all of the simple little things that could have saved their lives. I also worked through the physical motions of emotions that I imagined must have surfaced, slowly drifting towards sleep in the cold winter warmth.

Mike: It seems you found a way to create filmic, material analogues to your lived experiences, can you describe the technical abyss you created that allowed these translations?

Amanda: All of the editing was actually done in advance in the dance studio. I had mapped out the choreography second by second and planned every single shot and camera angle in advance. The film would involve 18 different shots. I even planned out which sections would be printed in reverse, slow motion, freeze frame, etc. During the shoot, we would sandbag the tripod, and mark the floor at the beginning and end of each take. We loaded three magazines with black and white film, and labeled each magazine as either Red, Green, or Blue. We would load the Red magazine onto the camera (black and white film), put a red filter on the lens, and film the Red choreography. Then, we would replace that magazine with the Green magazine (black and white film), put a green filter on the lens, and film the Green choreography. Then, we would repeat the same for the Blue. We did this for each of the 18 shots. We also recorded in sync sound, as I wanted to build the soundtrack using the sounds of my body (footsteps, skin brushing on skin, my body hitting the floor when it fell).

Once the film was processed, I logged it all carefully (as these black and white prints were now my originals that I would print from), using an analysis projector that I had borrowed from Christophe Runne. I used the slate as “0” and then on a sheet of paper I marked down the frame number of every significant action: the height of each jump, when the foot touched the floor, the depth of the landing, the turn of a movement. I logged the frame count of every single movement for each of the three colours.

Then I began the optical printing process using the Oxberry optical printer at Cineworks. I would load the black and white version of the red choreography on the projector, put on a red filter, and print onto colour film. Then I rewound the colour film in the camera, and loaded the black and white version of the green choreography on the projector, put on a green filter, print onto the colour film, and then do the same with the blue. This evolved into 45 days of non-stop testing and printing for 10-15 hours a day. I was determined that if I needed the lab to do any colour correction on the film that I had failed. The floor was 20% grey, the walls were white, I was wearing a black dress, and I had skin tone. I tested each of the 18 shots to find the correct colour filtration to achieve skin tone, black, white, and grey. I had these little Excel (accounting) sheets that I had printed out, and I filled in the details in pen. These sheets included the colour filtration, the neutral density filtration, the direction (forward or reverse), the ratio (high speed, slow speed, or freeze frame), the duration, and the frame count of each shot. Two entire walls of the optical printing suite were covered floor to ceiling with these pages. The project had gone from an intimate bodily experience in the dance studio to an incredibly cerebral and mathematic experience in the optical printing suite. One day when Chris Brabant came in to visit me he said that he had to leave the room because the amount of pages and numbers on the walls were making him anxious. Other people had similar reactions. I found that 10-15 hours a day surrounded by these detailed numbers, ratios, and the clicking sound of the printer had a noticeable effect on my psyche.

Once the testing was done, I printed all 18 shots of the film in one fell swoop, edited in camera. It took four days. After processing the final film, I found four mistakes and decided it was a failed film and I would never finish or show it. Several months later, Chris Brabant was surprised to hear that I had shelved the film. He was premiering one of his own films that he had made on that printer, and he wanted mine to premiere at the same time. He went ahead and booked the Pacific Cinematheque and told me bluntly that I had until November 28 to finish my film. So I hired someone to help with the sound design, I had the lab help with a few colour corrections after all, and that was basically it.

Near the end I had also gotten a FAP grant from the NFB to help with the post production. Once the film was finished I still had $1000 left over from the FAP, and the NFB said I had to spend it, but the film was already done. So I made several extra prints. This is why I often use this film to scratch test projectors before screenings — that and the fact that I am still bothered by those four mistakes.

Now that it is finished and has screened quite extensively, I still don’t know how I feel about this film. It is at once immensely personal and mathematically impersonal. Whenever I see it, there is a part of me that is proud and another part that cringes. I always see those four mistakes. In some ways this feels like a mere sketch rather than a finished work. Perhaps it’s the rough warehouse setting it was performed and filmed in. I had always intended to do a few more versions — that’s why it’s called Composition in RGB #1. But after finishing it, I couldn’t bring myself to make another one. At least not right away.

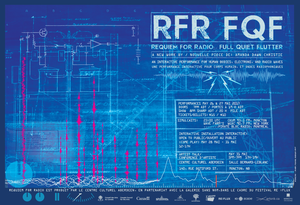

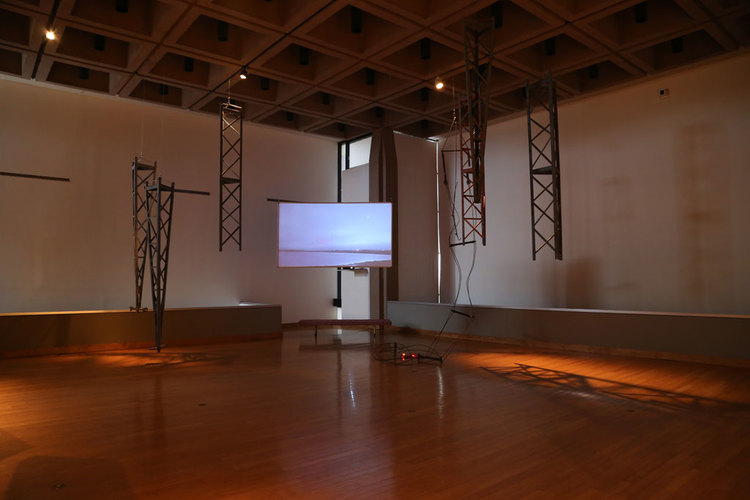

Mike: You have recently left Sackville, New Brunswick where you worked as the Production Supervisor for Struts, the fabulous and funky downtown artist-run centre. One of the tiny perfect town’s defining features (is it possible that in this one stoplight university haven, everyone is either an artist or a student?) is its radio towers. They have drawn you towards them, and inspired a number of works. Can you talk about them?

Amanda: The Radio Canada International shortwave towers have been a major landmark in the landscape of my growing up long before I even knew what they were. When I was a child, our family would go on trips to Sackville, Prince Edward Island, or Nova Scotia, and we would pass these towers. They are situated right next to the Trans-Canada Highway on that tiny bridge of land that connects New Brunswick to Nova Scotia and just before the turn-off to Prince Edward Island. They are located at the crossroads of three provinces. The field is a broad, flat, reclaimed salt-water marsh which many visitors have compared to the prairies. There are over a dozen red and white towers reaching up to the sky and connected by intricate webs of wires. The tallest tower is 110 metres high, so that gives you a sense of their dominance on this flat landscape. A hundred years ago, this was a ship building town, and it would not have been unusual to see the masts of tall ships in this area; now instead of tall ships it is the masts of radio towers. As children we would imagine all sorts of purposes that these towers might serve, for instance, as a trapeze or tightrope walking school for the circus. As an adult, I remember many trips home from the Halifax airport after long journeys from either Vancouver or Europe, and near the end of those three hour drives past midnight, I would see the red lights of the towers emerging from around the corner at Aulac, and would be filled with an immeasurable sense of comfort, as if the towers were saying “You’re almost home, you can sleep soon.” I’m not the only person to have this relationship with the towers, and I have started collecting oral recollections from other local residents in the area about their relationships to the towers too.

The towers send shortwave radio signals to Europe, Africa, South America, and the Canadian Arctic. They broadcast not only Radio Canada International, but are also contracted out by foreign companies on the other side of the globe, such as Radio China, Radio Japan, Voice of Vietnam, Radio Korea, etc. The radio waves bounce between the earth and the ionosphere, ricocheting up and down halfway around the globe through skywaves and groundwaves. They are situated here because the salt water marsh is good for conducting electricity for that initial groundwave and gives them a good kick off to send them as far as possible. Many people think that the towers send radio signals, but it is actually the wires in between the towers. The towers are merely the supports to hold the wires. This site has been under threat of being shut down many times, and who knows how much longer it will remain active in this digital age (although they do send out digital broadcasts too).

Some people say that they make you dream in other languages. Others suggest that they affect the productivity of the town because everyone’s internal molecules vibrate faster because of the radio waves. Some insist that the towers either attract or repel people from the town – you will either stay forever or leave as soon as possible. I find these stories fascinating and have started gathering sound recordings of these as well.

What I find the most intriguing about the towers is a scientific principle called “external rectification” or “the rusty bolt effect,” whereby two pieces of metal touching in just the right place, with a semiconductor (such as copper oxide) between them, can act as a diode and pick up the radio. Some old farm houses in the region actually tune in the radio via their old copper plumbing, so they can hear the radio in their sink. One woman describes how when she used to turn the water on in the bathroom, she heard Radio Tokyo. Another woman used to hear muffled voices from her kitchen sink at 8pm every night, but only for half an hour. There are many other stories of people hearing foreign language radio coming from toasters, blenders, speakers, light fixtures, clotheslines, refrigerators, and stoves. Over the past few years I have fallen in love with this sort of rural mythology.

I wound up pursuing a few projects related to the towers. In “The Marshland Radio Plumbing Project,” I took the electronic schematic for a regular foxhole radio, and transposed it onto copper plumbing. I basically built a complete radio out of copper plumbing rather than copper wire. When assembled it’s between 12 and 24 feet long and 4 feet high. The sink is the speaker and the diode is made from a poorly soldered joint with copper oxide between two copper pipes. The goal is to get it functioning without any electronic components whatsoever. I figure that if “radio sinks” can happen in “nature,” I should be able to manufacture one. I have taken my radio sink out onto the marsh several times in attempts to hear the radio. So far, it hasn’t worked. But each time, I photograph it, and I announce it to the public so that people can come and check it out for themselves. I became a bit of a “town character” that way. Locals who I don’t even know will ask me how my sink is when they see me in town. The photographs are quite beautiful, with the long flat marshes, the towers in the distance, and this long copper sink structure in the foreground. The sink stands in as a metaphor for the mythology and the radio waves. I would like to photograph it in many different seasons and weather conditions and to make a body of ten very large photographic prints. That’s on hold right now as I don’t have enough money for film and paper, but I’m confident that within the next couple of years I will have enough materials and images to work with.

The sink also works as a sculptural object in the gallery. I am hoping to compile all of the audio interviews into a 45-60 minutes soundscape and to install them on a small audio player in the sink’s drain pipe, so that viewers can walk up to the sculpture sink and listen to the stories coming out of it. Even if it never plays the radio, it will at least contain and transmit the oral histories.

Finally, I am working on a feature length, experimental documentary film about the towers. This would essentially be a landscape film that would use the interviews (in English, French, and Mik’maq) as a part of the soundtrack. That is still in the early stages as I have had no success in finding funding for that project. But I am determined to follow through with it somehow. Hopefully that will be finished in the next year or so or three.

Mike: Could you spare a few lines for Roberto Ariganello, local hero and lynchpin for the Toronto film co-operative, tireless flag waver for whatever was hand made and personal and independent?

Amanda: I first met Roberto back in 2003 at the IMAA (Independent Media Arts Alliance) conference in Regina. I was the chair of the board of AFCOOP (Atlantic Filmmakers Cooperative), and he was the executive director of LIFT (Liaison of Independent Filmmakers in Toronto). He was organizing a listserv for film production centres and was key in making sure that there was a roundtable for the film production centres at the IMAA conferences. He had a passion for making connections and links between centres so that we could all benefit from each other’s experience and resources. He noticed that larger film production centres in urban areas had more access to equipment as they were more likely to receive donations when companies went out of business or switched to digital, and that this was not the case for smaller co-ops in rural areas. Roberto wanted to find a way for smaller centres to share what their needs were, and larger centres to share what their excesses were. In that way, if a smaller centre needed something and a larger centre had multiple items of that something, perhaps the larger centre could donate it to the smaller one. And he wasn’t all talk — he really practiced and lived this idea as well. He was very generous with his time and resources. When I was working on some of my first films at AFCOOP, I would phone him up at LIFT to talk about film stocks, hand-processing, and optical printing.

The next time I saw him was at the IMAA conference in Vancouver (just a few months before I would eventually move there). It was during this visit that I had a few more personal conversations with Roberto and we talked about finding that balance between life and art and work. We talked about films that we were working on and different approaches to our artistic processes.

The next year, 2005, was the last time I saw Roberto in person. I was traveling across Canada by train. I had a SSHRC fellowship for my MFA studies and I was doing a lot of work about trains. I was traveling from Vancouver to Halifax and back by train. I was shooting 16mm film, 4×5 stills, and gathering sound recordings. These images and sounds would later become the source material for Fallen Flags (8:05 minutes 2008). On my way east, I stopped in Toronto, and it was my first time visiting LIFT, so Roberto gave me a tour and we sat and talked for a while. I was running low on film at that point, and he sold me some short ends, as well as an optical sound reader that he had kicking around. This was just before Kodak was going to stop processing Kodachrome (officially), and he handed me a few rolls of regular 8 Kodachrome. I asked him how much I owed him for this, and he said “Nothing. Just make a good film with it.” I gave him a hug goodbye, left his office and walked out into the hot summer afternoon toward the train station, with no idea that I would never see him again.

During the following year, Chris Spencer-Lowe (from AFCOOP) and I were planning a screening series for the summer of 2006. Chris was the production coordinator at AFCOOP and he taught most of the film workshops there. I had never gone to film school, as I had studied still photography instead. All of my formative training in motion picture filmmaking came from workshops taught by Chris at AFCOOP. We later grew to be friends and artistic collaborators. At this point, he and I were talking about the lack of experimental film screenings in Halifax and the need for some initiatives. Chris was especially concerned with the growing number of experimental filmmakers in Halifax who kept moving away. I myself was guilty of this. So, with me in Vancouver, and him in Halifax, we planned for a week-long event that we called “Cinema X.” It would take place in August of 2006. I was curating a screening of films that involved optically printed and hand-processed films, and I would teach a 2 day guerrilla filmmaking workshop that would cover camera, hand-processing, and optical printing. There were several other screenings and workshops planned for the weeknights. It was all going to kick off on Monday night with a screening of films by Roberto Ariganello. I was looking forward to seeing him again, although somewhat sheepishly because I still hadn’t shot that Kodachrome he had given me the summer before. In addition to screening his films, Roberto was also using this trip as a way to deliver a piece of equipment to AFCOOP.

You see, this is what I meant about Roberto really living out the ideologies that he put forth. AFCOOP had just bought some 35mm cameras, but didn’t have a machine to edit on. Meanwhile, LIFT had an extra 35mm Intercine (editing machine). So Roberto drove the machine from Toronto to Halifax. He arrived on the Friday before his screening to install the Intercine. My plane from Vancouver arrived on the Sunday before his screening.

My plane touched down in Moncton, and I went to visit with my parents before heading down to Halifax for the Cinema X week. Before leaving the house, I got a phone call from Chris, which was weird because I hadn’t given him my parents’ number. He must have looked it up. I was excited about the upcoming week and asked if everything was ready. His voice was heavy and dark as he simply said, “Amanda, something very bad has happened.” He told me that Roberto had drowned. I remember exactly where I was standing. I was in my parents’ living room, standing with a cordless phone, and looking out the window at the field behind the house. I sat down. He explained that Roberto had arrived and set up the Intercine on the Friday, and then on the weekend went swimming in a lake with a friend. He apparently had a heart attack while swimming and sunk. It was a T-lake, which means that it has high tannin content, and that makes the water very dark and hard to see through. As a result, it was hard to find him underwater. Divers came, but it was too late.

We talked about whether or not we should cancel the whole week of events. In the end, we decided that Roberto wouldn’t have wanted that. So we integrated his films into the screening that I had curated and dedicated the week of events to him. It was very difficult to go on with the programs.

“The Coast” is Halifax’s free weekly paper, and they had done an interview with Roberto and I a week earlier. They contacted us each by phone, me in Vancouver, and he in Toronto. The article and interviews came out on Thursday. It was difficult reading his words and the things that he had said about the Cinema X week before it had even happened — the week that he didn’t get to see.

I had made a bunch of handmade, zine-style catalogues with an essay I had written to accompany the screening. These zines had fabric covers (some were fun fur, some were velour, and I think some were felt). After Roberto’s death, I prepared an extra page as an insert to slide into each of the zines. The night of the screening, I presented my prepared talk, but I also shared some words and memories about Roberto, and explained the change in the program and the addition of his films.

Shortly afterwards, I was on a plane heading back to Vancouver thinking of Roberto and the Kodachrome he had given me that I still hadn’t shot. All of a sudden those roles of Kodachrome became more significant than ever, though I didn’t own a regular 8 camera to shoot them with. The man sitting next to me on the plane hadn’t said a word during the entire 6 hour flight, and I was thankful for the silence. As the plane began its decent to Vancouver, he began to talk to me about his daughter, and then asked what I did. When I said that I made films, he asked: “Could you use a regular 8 camera with a 3 turret lens?” I must have been unable to hide my shock and surprise and so he explained further. “I have a regular 8 camera in my basement and I don’t use it. If you think you could use it, I will send it to you.” I gave him my address and we sat in silence for the rest of the descent. Two weeks later, I received a box in the mail with the regular 8 camera, as well as a super 8 camera, and a 35mm stills camera.

Now I felt a deep need to shoot the film that Roberto had given to me on our last visit. I went to Victoria for the Antimatter Underground Film Festival, and took that camera and the film with me. The screenings only took place in the evenings, so I had the daytimes to myself. I wandered around with my new camera, filming images of water and wind in curtains. I had the film processed at Dwayne’s in Kansas (because the “official” lab had already shut down), and the images are beautiful. I still haven’t worked them into a film yet. However, upon my return to Vancouver, I began working on Fallen Flags on the optical printer, and this is where much of my grief was actually dealt with. It primarily showed images of trains that I shot on the trip the last time I saw Roberto, but I also used some images shot at Phil Hoffman’s Film Farm. There is an image of me swimming under water. The original is black and white, but I added a deep yellow and green filtration to mimic what I imagined the tannin coloured water looked like. It’s an image of me swimming and looking for something. Even though Roberto was still alive when I filmed this, it captured what I was feeling at the time. Imagining what it must have been like for swimmers and divers looking for him. For me, it captured something about the moment when I would open my phone book, and find his number still there, and I would forget I couldn’t call him up. I was re-experiencing the loss over and over again. As a result, Fallen Flags is a very dark film. The images that I shot on the Kodachrome that he gave me are very bright and beautiful, and I hope to someday make something more celebratory and light with them. As we talk of all these deaths, it makes me think that perhaps my years in Vancouver were much darker than I realized.