Barbara Sternberg: an interview (1991)

Barbara Sternberg hails from the Maritimes where she began using cinema as a philosophical tool. Her interests in memory and repetition seemed a natural fit for a medium whose material is time. Working alone, and using small, hand-held cameras, Sternberg uses the possibilities of stretching and compressing events, or presenting them in overlapping layers like a rush of memories, in order to pose questions about the way we have come to describe ourselves. In the nearly two decades since she began, she has remained faithful to her home-movie methods. But her project has been increasingly concerned with a recovery of transcendental ideals in everyday life. Even small gestures like cleaning and cooking have become rituals under Sternberg’s gaze. From our daily gestures of tending she teases out the echo of Judaic ideals, whose themes of exile and wandering can be seen written on the face of her many lonely voyagers. Her son struggling up neolithic mounds, foundry workers casting molds, a burning collection of porn stars — Sternberg gathers these and others in a spirit of communion. Each moment tells the story of its own creation, its own history, and invites us to enter.

Barbara: I never thought of myself as an artist because I don’t have that kind of background. The only work I made was very personal, and I never thought about it much beyond giving it to the people I’d made it for. Now I’m coming to think that this personal work is a lot more important; it’s where a lot of work should remain. I made things for anniversaries and birthdays. I made books for my parents which used photos and texts in ways that are pretty similar to the way I work now. But because it was for the family I never… I just liked doing it. The first film I made was with my father’s 16mm camera. My husband at the time didn’t have any home movies and barely any photographs from his growing-up, so I wanted to make him a home movie, to create a past for him. But I never thought of it as filmmaking or art or anything. He was a football player, and I would watch the games and sit through these boring half-time shows. So I came up with some ideas to make them better and wrote a script and approached a television station, which bought it. I couldn’t believe it. But when they aired it, they showed the usual visuals, which made the whole thing boring again. I decided to go to Ryerson Polytechnical to learn how to make films so I could tell people more clearly what I wanted them to do. But once I was there, I didn’t think at all about industrial film, I just started making stuff in a way I would later learn to call “experimental.” It was the way I worked, the way I think. I didn’t want film to be just a recording mechanism, simply translating literature or theatre. But my approach didn’t go over at Ryerson. I got a super-8 camera when my son, Arlen, was born and often made footage with him. He was two or three when I went to Ryerson. I never thought of this shooting as having any relation to my schooling at Ryerson. Everything had separate little categories then.

Mike: And when you left school…

Barbara: I was committed to film on some level, but left without the confidence to make work. I was a non-person there; no one ever looked at my stuff. So when I left I just went back into myself. I think it was good in a way. I turned to super-8 instead of 16mm because I didn’t take myself seriously as a filmmaker. I went back to teaching high school. I made little super-8 films which often involved my son and my husband because they were around. I made my own motorcycle film à la Kenneth Anger, and a karate film — small editing exercises which were never shown. It was partly to get Ryerson out of my system, to reconnect with myself, to rid myself of that professionalism. The marriage ended and I moved to New Brunswick. I was teaching at a community arts centre, and started making little things in super-8 with the boats, the shapes of the waves, the rhythms of the water. Just to do it. Then I made Opus 40. It was about the people in the foundry there. Then I made Transitions. David Poole saw them. He was working at the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre. He said, “Why don’t you distribute this?” But I never thought that I was making them to show others. I think I do better that way. The first film I got a grant for was A Trilogy and I felt watched, like there were expectations, that it should be something people want to see. I think it tightened me up. Even now I feel better when no one knows I’m doing anything.

Mike: Tell me about Opus 40 (18 min 1979).

Barbara: The arts centre where I taught had a goal of using the arts to help students think creatively, and to involve them in an art making that made sense with their living. One of these projects brought us into the foundry. There were two main employers in Sackville — the foundry and the university. Often at school, the foundry kids seemed divided from their family life. So we went to the foundry altogether as a school. There were two parts to the foundry — an old one and a new one. The old one made moulds out of earth imported from France. They would pack the earth down and pour molten iron over it which hardened to form parts for wood burning stoves. The modernized foundry made electrical stoves, but we were interested in the older foundry. It had used the same process since 1837, and the men who worked there thought of themselves more as craftsmen than the assembly line workers in the modern plant. So we brought the kids in and they drew the men’s gestures, or made rubbings, or sound collages with interviews of their parents. All the material was collected from the life that was there. I liked coming into the foundry and wanted to ask the men about repetition and, finally, to make a film about it. I was thinking about habit, ritual, the sun rising daily. Both the building and the work it contained were very repetitious. So I made a plan on paper and interviewed the men.

Opus 40 isn’t my fortieth film; it’s a reference to their forty-hour work week. It starts out as if it’s going to be a documentary. The camera moves into the factory cinéma-vérité style, and a voice asks, “How long have you been working at the foundry? Which area do you prefer?” Then the film begins to perform its own form of repetition, the image divides and divides again. The interviewer asks, “How do you handle the repetition?” But there’s no answer on the soundtrack. You don’t hear the voice-over again until the end. The film cuts to an image split in half, with the workers on the top and black on the bottom. I thought of the black part like a bass rhythm in music. My plan was to show a single man working in both parts of the image, top and bottom, only shot at different times. It would be the same gestures, only making different moulds. So it wouldn’t be a strict repetition, but almost. This was all done in-camera. I’d borrowed a Fuji super-8 camera, which allows you to rewind. I rigged up a matte box and stuck paper in it to block out parts of the image or introduce coloured filters. I wanted to embody the process of repetition in my gestures, so it wouldn’t be as if, oh they do that and I make films. Because film is founded on repetition. The claw runs up and down, the shutter goes round, and I’m moving these filters in and out of the box.

I never used the best footage I shot — the pouring off of the moulds in the afternoon — because it didn’t fit my plan. It was too beautiful. That’s one of the differences in the way I work. I don’t like to use images that are monumental or create a sense of awe in the viewer. I think the first time it clicked in me was seeing a Herzog film which just reeked of the Beautiful. I was so impressed. It was about filmmaking and power on a big scale, and about what he had to go through to get these shots. But there’s a certain contrivance which ensures that everything in the frame is a carefully made image. I feel better keeping things smaller and rougher. My stuff works through an accumulation of the everyday, more through a glance than a look, less a controlling gaze than an observational one. What you hear is the sound recordings of the foundry slowly giving way to the sound of the projector. Then I took the split image and shot it off the wall to create further repetitions in the image, and this move is followed on the soundtrack where the sound is channelled through an echo machine where it’s made to double on itself. The image becomes more fraught as if all the days of their working were happening at once. Then I repeat the question, “How do you handle the repetition?” And the man answers, “What do you mean?” [laughs] It’s so wonderful. He says, “I come in every day. I have so many moulds to make and I do this task.” He’s been here for twenty-five years, and for him the work doesn’t have the negative labels we might attach to it. Gertrude Stein wrote that the history of each of us comes out in our repeating. Repetition can become deadening when you don’t notice all the small differences in it. I thought the workers might complain, but they didn’t.

Opus was invited to a MayWorks screening which annually celebrates labour in art. All of the films in the program were documentaries complaining about working conditions. Except mine, which was experimental. Some people were angry, saying, “How dare you make a film that accepts this? Why aestheticize this experience?” I didn’t take the opportunity of filming to help change conditions at the foundry. Whether a film could really change them or not is another issue. I felt if we could come back to being connected with our labour, we would be more human. The film is an experience of repetition and not finally about their work. The film is not about something, it is something. Opus came out of notions of repetition that were more intellectual than lived.

In Transitions (10 min 1982), I wanted to make something more personal. I always felt there was a time-lag between events and their recording, that events in film were inevitably a re-creation. Film suits memory very well: its making is always a going back. But I wanted to make something that wasn’t over before I made it. I wondered if I could make a film about the present, a perceptual documentary perhaps. I would recognize things I saw as “right” and film them — the evidence of wind on snowbanks, or water, or hay, for instance. But, again, I didn’t want to shoot it like Nature Beautiful. No capitals. You write in your journal, you collect bits of film, you talk to people, and at some point it comes together enough to think: oh, this is a film. I was thinking about a state of transition which is characterized by the fact that nothing is singular or clear. I felt there should be a lot of motion, that the film should never rest so you couldn’t make easy orientations. I wanted to layer images for the same reason, so you can’t just make out a single moment because this is the way our minds work. When you’re agitated, the past, present and future – if there are such divisions – are going on at the same time. So I had these fragments and some ideas about how to treat them. But I needed something to unify the material. So I made a narrative ground. I shot a woman in white on a bed, who’s sleepless and agitated. There’s other images of her as well — walking on a river bank with a guy, someone touching her face, her in a restaurant, sitting in a chair with her knees up. But I worried that the central image of her in bed would overdetermine the other images, that they would be read as her dreams or something like that.

Mike: There’s a very brief shot of her walking with a man and all of a sudden the whole film aligns itself around this image. There’s been a relationship, but now she’s alone and can’t sleep. Obviously they’ve broken up. Why? She’s having nightmares; something about her past is troubling her. I wondered at how little it takes to make a story, and how much it takes to conjure something else.

Barbara: Transitions came out of waking up afraid every day. Terrified. That’s what occasioned the film. I wondered why we had to get up, to face every fucking day. Some societies create this feeling of disorientation and fear and confusion as part of an initiation rite which provides passage from one state to another. For me, it was something else. The soundtrack consists of two voices whispering. The difference between the two is that one is talking about personal things taken from my journal, while the other is quoting from a physics text. The journal stuff talked about the face of my mother. One day I just realized how long I’d spent looking into her face so I wrote about…

Mike: How much of her life was in her face?

Barbara: How much of her face was in my life. [laughs] Later, the same voice describes a conversation where my mother says, “He’s your husband. Do what he says — it won’t hurt you to meet his parents.”

Mike: This track is a lot more buried than the other one. I’ve never heard any of this stuff after seeing the film a dozen times or more.

Barbara: I was more concerned with having a personal tone than having details spelled out. A friend of mine felt the film was about the space women occupy between mother and husband — neither is tenable. She described the film in terms of a power relation I hadn’t thought of. The woman in the film wants to live in the present without the expectations of the future or the visitations of the past. To be awake to life, not back in the womb or sleepwalking. Sometimes the voice carries minute descriptions of physical activities — walking, for instance — to try to get the mind to focus completely on the sensations of the present. The last line asks, “Do we have to be aware of every moment?” In all my work, I feel it’s too dishonest to provide a resolution — as if I have the answers. So she stays on the edge of the bed. The film whites out and leaves us with the question and her with the choice.

Mike: I felt the two voices come together in the line that asks, “What more frightening thing could there be than there is a present moment?” I understood this as the possibility of an infinite present, that the next instant I could think or do something that might continue for the rest of my life, that the images we make constitute a place of perfect memory, where we can return to these consequences, where we can learn to travel in time.

Barbara: Yes, the clearest memories I have are in photographs. This film, like Opus 40, is also about repetition. What’s memory if not the order of our repetition? Or history? Or identity?

Mike: Let’s talk about A Trilogy (43 min 1985).

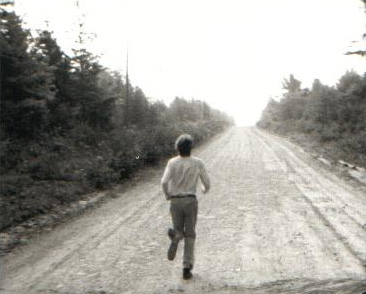

Barbara: It’s framed by a woman at the edge of a pool. It opens with her about to dive in and closes with her dive. The second shot of the film runs eight continuous minutes and shows a man running along a dirt road. The road is tree lined and narrow, so it’s as if he’s traversing this passageway. The camera tracks alongside him. A male voice-over recites fragments from a story: “Duration didn’t come into it.” Or just: “Time. Water.” Things like that. There’s suggestions of death. I actually asked him to talk about what it would feel like to drown and cut his response into fragments. A scrolling text follows which lists historical events. Then there are six kitchen scenes that show a couple in the morning before they go off to work. You hear bits of dialogue about whether the repairman is coming, or who’s driving whom to work. Then a baby carriage is introduced, and a baby which each of them take turns feeding. Meanwhile, news reports relate an airplane crash at sea. A second text follows. This time instead of a list, it takes the form of a narrative which relates the initiation rites of an African tribe. In order to prepare him for adulthood, a boy is circumcised while the villagers mourn him as if he had died. He is cast out and goes through this harrowing experience, then is re-named and told about the existence of the Tree of Knowledge. The next section follows a young boy running up Silbery Hill in England, which is a Neolithic mound, a fertility symbol. Like Transitions, this section is pictured in layers — images seen in superimposition. So we see the boy on the hills rolling through images of water, and volcanoes erupting and a pregnant woman — archetypal images. This sequence culminates in the cutting of the umbilical cord.

Mike: Doesn’t it suggest that each separation replays this initial loss of the mother?

Barbara: It’s cyclical. We’ve been listening to letters from the mother to the boy which lead us to the cord’s cutting and then we hear the boy’s voice for the first time. He’s talking about his choices for the next year, his subjects at school. I thought it would be too utopian to show him being free. He comes into his own, but he does so inside a system. The world is organized into subjects of knowledge — geography, history, math. A third scrolling text follows with a list of questions. Then the three stories — the man running, the couple in the kitchen, and the little boy — all find their endings. The man runs up a hill, and the camera stops and lets him move towards the horizon. The couple are always seen in the morning, but today is Sunday, so for the first time they’re not getting ready for work. You can see the backyard, and she takes the baby in her arms and goes out of doors. The boy runs up the hill and rolls down without the intervention of the other image layers. The woman dives into the water and the film ends. Over the closing credits a piano is practicing scales, continually missing and beginning again.

Mike: The film brings different people together with experiences that they’ve either forgotten or never learned how to remember. It seems especially directed towards the males in the film who are always running, unable to look back and take account of what’s passed.

Barbara: I was thinking of the “running” as “living” — for which we can’t “know” the beginning or end. Five years after I finished the film, I read The Mermaid and the Minotaur. The author posits that the male world of work and enterprise is based on two things. First, to create a world distinct from the mother who provides our first experience of ourselves when we’re powerless. We escape this lack of power by latching onto the “not-woman” — the man. The father doesn’t remind us of this period of helplessness. The male world of work is founded on signing, on creating identity, and an important aspect of that is to control women, to exert power over them. Second, the world of enterprise is part of our denial of death. Even when women enter that world they do it vicariously through the achievements of sons or husbands. Or they do it in support — the women behind great men — as secretary or nurse. So they’re allowed in, but only beneath men. Her thesis is that until you have both men and women nurturing children through that helpless stage of the first couple of years, this will continue.

Mike: But aren’t these polarities drawn together through memory? To remember or bring back again is an acknowledgment of death. Because going back always returns to the acknowledgment of those already dead.

Barbara: The child dies to become an adult, but the mother dies also. The rituals that remain to us negotiate this passage between states. These old rituals of earth mounds and fire and water aren’t active for us anymore. Even as I put them in the film, I did it with the understanding that they aren’t the same for us as the builders of mounds or carvers of rock. But there’s something that remains, and these traces are felt in our everyday life. We don’t have to go somewhere else to find the mystery of that connectedness. It’s always there. We have flashes of it — some image, some moment that stays with us. Unaccountably. The couple who appear as if out of an advertisement for the desirable life are finally animated by the presence of a child. It’s not the only signal of life’s mysteries, but it’s an obvious one. We don’t have many rituals. We have habits. But a child brings us closer to something else. I wanted to fill the film with the mystery of the everyday, of those moments which we haven’t learned how to attach words to yet, when you feel everything is different but you don’t know what it is, like the hair on the back of someone’s neck or a young girl running across the road. You feel something, like memory, or the understanding of those already dead.

Mike: I felt that the camera pans over Silberry Hill and the child’s rolling ascents and descents marked a re-invention of ritual. The camera passes over this landscape again and again. Your son finally appears inside these pans, as if lured by this rhythm, and the two of you begin a kind of dance. You have flown across the world to bring him to this hill, to a place where you can impart some last understanding — the memory of your time together; that night of nine months. He shows in his rolling over earth that he remembers the unmistakable connection between the two of you, and understands also that it is time for him to leave. It’s a remarkable section.

Barbara: It’s as if the hill is trying to reclaim him. As if he’s trying to be free of it. The woman’s voice is trying to hold him at the same time, and then he has to let go. Separate.

Mike: Did you get any kind of support for this work?

Barbara: I got money for the first time — my first grant. I came to Toronto late in 1984, just after I thought the film was finished. I had a fine cut and was ready to mix. Then I found out all my tracks were no good because they’d been transferred improperly. I thought I would die. So I retransferred the sound, cut it back again, and started making changes. Then I started changing the picture again, redid the mix, and finally released it the next year.

Mike: It’s a film that’s been widely circulated.

Barbara: In terms of experimental film I’ve been fortunate. But the fact that it’s been programmed doesn’t necessarily give me confidence that people think a lot about it.

Mike: Why is it being selected then?

Barbara: Moving to Toronto introduced me to the politics of exhibition — how and why certain works get picked. A lot of it is who gets chosen. I think my early films were considered good apart from the identity of their maker. There wasn’t as much consciousness about being a woman artist. Now we’re in a very self-conscious phase of change. Because my work was taken up by a largely male faction I was ignored by feminists for a time, as if I’m part of a male thing. Or perhaps my films aren’t as “feminist” in subject matter. There are also considerations of race. All this helps to open the canon up, remove its stronghold, but it’s complicated. The danger, of course, is “political correctness” being adhered to mindlessly. I see other filmmakers much more active in getting screenings for their work, but I haven’t done that and I don’t care to. Some people are smarter about distributing their work than making it. There’s a lot of energy that goes into seminars and posters and distribution these days.

Mike: Does this focus on distribution signal a shift?

Barbara: The equation of money with value predominates and that’s a problem. I’m not trying to romanticize poverty, but does money make the art better? Give it more impact? The sense of surface and advertising that permeates our world is also permeating our work. Which is not to say we should live in shit, but this feeling that making slicker work makes us better artists is not necessarily true.

Mike: Do we need an audience for this work — do numbers matter? Is there a certain point where public attention wanes so completely that you have to say, okay, let’s pull the plug on this. What if no one comes?

Barbara: That’s fine. Then I’ll make it for myself. I think the work has an effect nonetheless. Things exist in the world. Look at Gertrude Stein — she was forced to publish most of her work herself. And her writing continues to be felt. I don’t think its implications have yet been realized. But the fact that she wrote what she did, when she did, changed everything. Which is not to argue for dead authors. But if she’d made the decision to stop working based on her audience, she never would have written anything.

Mike: Why is it important to make fringe film?

Barbara: Why is it important to do anything? I just do it. What sustains public attention isn’t necessarily good. It’s better for me to make this work than do horrible things to people. If the role of art is to ask us to go deeper, to remember certain things, where else is it going to come from, apart from art? Is it going to come from a film that supports the status quo even as it’s attempting to critique it? Even if it’s against the Gulf War, for instance, but takes shape as a sponsored television documentary, this work still supports the system. It begs certain questions the filmmaker can’t afford to hear because finally their work needs to sell.

Mike: Tell me about Tending Towards the Horizontal (35 min. 1989)

Barbara: I was in Moncton, New Brunswick, walking past houses, and there was that moment, you know, of looking up when something just clicked, and two years later it was Tending. Around that experience I began to collect material about houses and bodies, and I read books that seemed to relate to these themes. I didn’t want to use images as symbols the way A Trilogy did. I wanted the image to be more incidental, to cast away the signifier. I wanted to communicate something else. I didn’t want someone to view the image as a series of identifications, of words — house, person, car, building. I didn’t want someone to read the film, I wanted someone to see it. So I was collecting images I knew I had to have without quite knowing why. Then I met the Acadian writer, Frances Daigle. She had seen some of my films and said she’d like to work with me. I thought this would be a good way to allow the words and pictures to become more fully themselves. To let her write the words for the soundtrack, and for me to make the images. The film pictures houses, initially presenting them as they are, and moving to a point where they become light, shadow, and colour. For their occupants, these architectures mean home, but for a passerby they remain a divide, a line between inside and out. Something is going on in there, but I’m out here, and the structure that’s holding us apart is endless and immovable. So I took the light of the window, the orange light, and allowed it to fill the whole frame so that we could see the scene inside out. The film describes the dissolution of these rigid structures until they become alternating passages of orange and blue light. These are the two colours natural to film, so the film’s end signals a return to materials.

Mike: On a scientific level, it would be that moment where you experience a table as a bunch of atoms. Was the architecture important?

Barbara: When a child draws a house, she or he makes a rectangle with a triangle over the top. The opening houses look like that. In the middle section I wanted houses that were increasingly covered by foliage and vines, that showed some merging of architecture and surround. A newspaper reviewer wrote that they were “middle-class” homes, but I wasn’t thinking about that. I was simply thinking “house.” But in Toronto now, everything recalls class, race, and gender.

Mike: Throughout Tending I felt we could be looking at anything. The show of houses was immaterial. This seemed the real aim of the film — to do away with the fact that the image “stood for” something. Maybe we could say that the film is crafted out of a certain kind of knowing, a way of living in the world. It’s like the woman described in the voice-over who sits in the library reading any book. She doesn’t care which one, because the feeling she carries is already there. How did you arrive at the title Tending Towards the Horizontal?

Barbara: At a certain point I’d shot footage that had a split image, like in Opus 40, but now split horizontally and vertically. I was trying to choose between the two and finally discarded them both. But before I did, I remember saying to a friend, “Oh, I think I’m tending towards the horizontal.” And she said that’s the title of your film. [laughs] I don’t give a lot of time to titles. For some people the title is the work. Some people’s titles are so fabulous I don’t need to see the films.

Mike: You called your new film At Present (18 min 1990). How did it start?

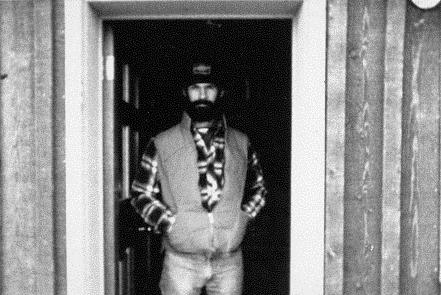

Barbara: I was teaching, so I didn’t have a lot of time to work on film, but I wanted to keep my hand in. I had this footage I liked and wanted to make something with. I kept seeing all these male Toronto filmmakers making work about love. So my film is a response to these films. It has three sections. The first shows four individuals in four settings — two men and two women. All four are framed by houses — a man in a doorway looking out of the house he built; a man smoking; a woman who alternates between picking through broken glass and potting flowers; and a woman sweeping a studio floor. The soundtrack over each relates a parable. Then there’s a House Beautiful-type of apartment, and I run into the shot because one of the features of these male films is that they would always appear in their own films, so I thought I had to show myself somehow. So there I am primping in a chair, trying to fit myself into a life where I obviously don’t belong. In the course of making the film I interviewed a number of men about love. One voice-over begins with an evocation of media clichés — he talks about falling in love in Paris, about the Hollywood romance contained in Casablanca, and about his childhood in Niagara Falls, which remains the honeymoon capital of the world. Then there’s a chorus, or middle section, where another male voice asks, “What’s involved in love? Is it power — is that what we’re talking about?” With a single exception, all the voices in the film are male because I wanted to make a film about love that men would hear. If I had women talking, men would think it’s a woman’s problem.

Mike: So this is a film addressed to men?

Barbara: Well, both men and women really, but for men to hear better they had to be addressed in their own voice. As the voice-over continues to speak about the body and its traces, the images change. They move outside now. They’re not so enclosed, and you don’t see as many couples. People are in more contact with their environment. We see people setting fire to a field and a woman’s voice reciting from R.D. Laing, “They are playing a game. They are playing at not playing a game. If I show them I know the rules, they will punish me. I must play the game of not showing I know how to play the game.” Another male voice begins more tentative than the last, accompanied by the rising sound of women laughing. The burning field is superimposed on a number of naked men taken from pornographic magazines. Another voice intercedes. It says, “Love, hate, he, she — it’s all the same, isn’t it?” The images of fire return to the apartment with a series of snap zooms which break open the space so that the house structure, which is the support structure of this coupling, opens up to another formulation of love which is more encompassing. The film turns to light and the talking becomes laughing. The beginning of the film shows an Aboriginal man opening his mouth as if screaming or calling, and the last shot shows a contemporary, an older man from this society, again in silence, and he’s looking out at the audience, and then he makes this little smile. This smile is really the beginning.

Mike: To risk an obvious question: why an Aboriginal? He feels like the image equivalent of “once upon a time” — a prelude to this male intercourse. His silent shout evokes a flash of light which lands us inside a Toronto living room. At present.

Barbara: I remembered that shot from a television documentary I saw in Saint John eight years ago. I didn’t know why, but I knew I had to have that shot — it was the only one I took intentionally for the film. So I tracked it down and shot it off the Steenbeck. It was important that it was a shout and that you heard nothing, that there’s an expression coming from the mouth that wasn’t words — because the rest of the film was full of words. It comes before the title because it’s before language, in a way, like laughter is before or beyond words. What did you think of the film? You’re in it.

Mike: It’s your best work. The light is clearer and the montage is lovely and always unexpected. I could move alongside the changes without feeling either that I was being hijacked or completely disoriented. It struck a number of very different emotional registers and managed to negotiate them with great elegance. It also has the angriest section I’ve ever seen in your work, which you pointedly ignored in your description of the film — a section which plays over my voice-over. It shows a number of gay porn images of men naked, erect and burning, mutilated by fire.

Barbara: Or “on fire,” “burning,” “hot.” The fire theme was introduced with the burning fields, which are set ablaze every spring to burn off old grass and supply nutrients for new growth. This burning field footage was actually from an artist’s [Bill Vazin] site piece. Art, fire, spirituality… layers of meaning. As to the choice of male nudes, I wanted to show men what it was like to show their bodies, so I put their bodies up there. As if they’re images of love, or whatever the excuses are for always doing that to women. As if they were about anything but power. The film is moving toward a more open and encompassing view of love which is no longer oriented to some exclusive “I love you.” This section marks a regression. It speaks of division and the objectification that comes out of fear. But there’s a lot of laughing in the film, even in that section. So you could say that women have the last laugh.

Mike: And the title?

Barbara: I was going to call it Love Me. [laughs] I called it At Present because it’s like the end of a sentence — the way we are at present. This is sort of where we’re at, a news report on the state of love. It’s also a questioning of where the present is. Is the present the Aboriginal image that opens the film or the apartment that it moves to? Which are we present to?

Mike: People are usually featured in At Present moving in a directionless isolation, like much of your previous work. Tending is a road movie — going where? Your son is running up the hills of England only to roll down again. The sleeper in Transitions never leaves the bed, though there’s a constant flow of images. The worker in Opus 40 is always in motion but always appears to be doing the same thing.

Barbara: But that’s all there is. There’s no place to go. I make films that I wouldn’t like as a viewer. I wouldn’t go to my own films. The stuff I like is not the stuff I make. I like Snow’s work. I like conceptual, minimal work. And yet my work is multi and messy and accumulates meaning through fragments which are layered and more personal. Seeing work and making it are two entirely different things.

Mike: Do you think criticism is important for film?

Barbara: Because film exists only in the time of its projection, it’s crucial that there be writing. Writing endures. It gives work continuity. Many more people have read about Mike Snow’s films than have actually seen them. It’s given that work an existence it wouldn’t have otherwise. But who will write? Maybe criticism should come from other filmmakers — but the way we show our work is no good for discussion. And filmmakers don’t speak to each other about their work. We’re afraid. People work alone. Personally, I get confused by other people’s opinions while I’m working. Painters make reams of work that never gets seen. But that’s a weakness in film — if you make it, it has to be seen with a poster and press and stuff. I think we shouldn’t worry about it so much. There’s lots of work and what’s good will stay around somehow. And if not, so what?

Pecking: Barbara in the 90s: an interview by Mike Hoolboom (2000)

Originally published in the monograph: like a dream that vanishes: the films of barbara sternberg (ed. Mike Hoolboom, 2000)

Mike: The closing title in Through and Through (63 minutes 1992) reads: Anne Frank died in March 1945. I was born in March 1945. Do you feel that you are carrying on Frank’s work in some way?

Barbara: There are a number of photographs of women shown in the film: Gertrude Stein, Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, Anne Frank… then others not as famous, friends who died young of breast cancer. As I read their work, I identified so strongly, it’s as if I was them, or they were me. The proximity of Frank’s death and my birth made this connection personal. I am connected to this line of women. Virginia Woolf talks about thinking back through our mothers in A Room of One’s Own, a book which asks why there’s so few great women writers. You can’t be who you are without the efforts of those who have gone before. She wrote on the backs of women, many of them anonymous, who might have written a single poem and stuck it in the attic, and after a time, all those poems made Virginia Woolf possible. It’s the same for me. Without these women, I wouldn’t have made this film.

If Virginia Woolf was a filmmaker she would make my films! (laughs) She wrote about ordinary daily events in a way that has strong connections with cinema. The light shining on a cupboard was as much an event as someone walking through a door. She used the ellipsis (…) a great deal, leaving phrases open. Memory doesn’t belong only to the past but is an “arrow of sensation,” is past and present. She writes of events or objects surrounded by blurs, or covered by a veil, which seemed filmic to me. In The Waves she wrote about drops of time, the impact of the present moment dropping.

Mike: Through and Through also includes a series of texts about breast cancer, listing the names and dates of women who have died young.

Barbara: It’s a fear you live with every day, at least in my life. In Transitions this was expressed as a fear of living, of wanting to go back and pull the covers over one’s head and be unaware. Fear of living or of dying, it’s the same in the end. I feel lately that I’m obsessed with death — well, not obsessed, but it certainly figures in my conversations A LOT. When I was a kid I was afraid of dying and not just for myself. I was afraid of anyone’s dying! And if something went badly I’d want to go back and have that time again. I would get so upset because now that time was ruined and I couldn’t get it back.

Mike: Why does this movie look different than the work that came before it?

Barbara: The film was shot one frame at a time. I’d been editing pictures closer and closer together in previous films, joining moments shot at different times. I wanted to push that further, to connect discrete moments to achieve a simultaneity. So while there is fear, it’s set within the big picture, the eternal. There’s an equally strong sentiment that the world is amazing. Beauty and terror are part of the same thing. Beyond the meaning of any particular shot, I wanted to transmit this energy.

I had been collecting a lot of feminist writing and writing on the Holocaust. Although I wasn’t there, it affects me greatly, and hurts me. I thought if I could make a film about it, I’d be done with it! I read interviews with children of Holocaust survivors and Nazis, as well as interviews with women interned in mental institutions. These interviews were excerpted and collaged into scripts for the sync sound sections in the film. Originally, I’d planned to have a lot of voice-over from all this material I’d collected and loved, and then I made the decision to separate the sound and image. In place of voice-over I wanted to re-locate language into the mouths of speakers.

Jean Marc Larivière played a child of a Holocaust survivor. Maighet Pugen played a girl placed in a mental institution because her mother couldn’t control her. She also played the grand child of a Nazi executed after the war. They had certain themes in common. Secrecy. The burden of history. And control. Jean Marc talked about his parents and their fear of losing control. They would get upset if they saw their kids expressing anger. In another segment he says that he doesn’t have a life of his own. That thousands of people live through him. The incarcerated woman also raises issues of control. As women we have a very limited band of acceptable behaviour. I read about a woman married to a minister, and for a while she wasn’t keeping the house clean enough. When she stopped doing the dishes he had her put away. I felt it was appropriate to put these problems of power in language. Because language distinguishes, between cup and table for instance, and insofar as it distinguishes, it divides the world. With division comes conflict. So while the images in Through and Through worked to bring events closer together and eliminate boundaries, language showed places of conflict and difference.

The film is structured around a series of journeys which go further afield. There’s a trip to Montreal on a train, another to Algonquin Park. The ultimate trip was going to the Arctic. It was a quest for origins, or authenticity perhaps. It was the furthest one could go. The Arctic footage bookends the film. I often do that because it suggests a spiral, a cycle. When we arrived at the Arctic the first thing I saw was everyone else with their cameras, so I started filming them filming It. The Land. The Amazing. The Source. What we all came so far to be wowed by. Initially, the land is shown only peripherally. In the end, people get out of the boat and onto the land. They were filmed to minimize the distinction between figure and ground. It’s black and white, often a bit blurry, highlighting shapes and outlines. The figures often look like an extension of the rock. The boundaries between people and things are dissolved. The film is about these boundaries, or lack of them.

Mike: Beating (64 minutes 1995) takes up many of the same themes and problems.

Barbara: All the unused voice-over material for Through and Through haunted me. In a way, it spawned the two films which followed. The brief, sync-sound sections in Through and Through speak of oppression, identity (I/we), and the pressures of history on the present. Beating takes these issues up again, seeing history through the personal, expressing the anger, fear and pain suppressed in the denial of oppressive situations. Beating looks at the parts of ourselves (myself) hidden in shadows. The existence of evil and horror. Questions without answers.

Beating is filled with voice-over which provided the context for the images. Like Laurie Anderson says: This is a record of the times. It’s the thinking, the issues, the terms, the where-we’re-at in terms of social history. The film uses black and white high contrast footage, both negative and positive, bleached, scratched, and sometimes bi-packed together. Positive and negative are present visually as well as symbolically: good and evil are two sides of the same coin. As much as I want it, I can’t only have good. There’s bleached footage of a young girl primping, innocent yet sensual, with the words cunt and bitch scratched on her. A newspaper photo shows Syrian Jews hanging with placards around their necks, while a series of supers move over them. Whose story becomes history?

The film was edited in sections that were internally cohesive in terms of content and treatment. From section to section repetitions occurred and connections were made, equivalences between different images achieved the feeling or recognition that everything was related. Everything exists in each moment – it is all there all the time.

In my previous films I moved towards the light. But in this film, I thought, okay Barbara fess up. Can I reveal my anger? Am I brave enough? So I decided to show it. I made a large voodoo-type doll of Hitler, a primitive-looking doll with a photo transfer of his face. I wanted to film myself shitting on him, like when one says “Shit on this” meaning I’m through with it. Diminish him The camera ran out of film before I could poo, but I did get to poke out his eyes and cut off his little penis. This was all done in my kitchen, in a domestic setting, because I live these big historical events in my apartment. Which is where I like to work. I film the shadows on the wall of the neighbouring apartment, or shoot my mother or son or whoever’s around. Issues of power and seeing are played out in daily life.

Mike: Your mother appears in the film. She’s lying in bed, eating toast and reading the newspaper. She’s shown in close-up, where you focus on the wrinkles of her face.

Barbara: It’s the view you would get only if you were her daughter snuggling up close on her, which is what I would do when I was little. An intimate bodily experience. Along with the following images of Jim MacSwain (a friend) who sits chewing his nails, fingering his toes, and eating grapes, mean: somebody actually lives all this. History is not abstract, but embodied. These shots are rests, still points in the film.

Mike: Most of the voice-over text is quotation, but some of it is yours.

Barbara: The one passage I wrote is repeated in the film by both male and female voices. This makes ambiguous whether it marks a response to the pain of a woman or of a Jew, or for that matter anyone else. Viewers can fill in their own painful situation. It says: “I want revenge, I want you to know how it feels…” and then, “I want you to say you’re sorry so I know you’re sane, we’re the same…” It’s something I wrote a long time ago to my husband. My then husband. My no longer husband. While making the film I felt I also wanted to say that to Germans, or to Germany — if you can say something to a nation.

Mike: Tell me about the title.

Barbara: Beating suggests the thing and its opposite. The sun beats down and warms us but it can also burn. The wings of a bird beat and so does one’s heart. At the same time a beating is a fist fight, or you beat yourself up with these issues. The myriad of positive/negative associations from the word beating make it a good entryway into the film. There are many beating images in the film. Like the birds.

Mike: Why so many birds in the film?

Barbara: Maybe they’re us, maybe they’re me. The birds are pecking, being frightened and fluttering up in the air, then settling down again and eking it out. Surviving.

Mike: The voice-over ends with a joke that gestures towards reconciliation. Can you tell it?

Barbara: A man is walking down the street and a car pulls up beside him. Who should get out but Hitler. Hitler stops the walker, saying, “You’re Jewish — what are you doing here?” There’s dog shit on the curb so Hitler puts a gun to his head and tells him to eat it. The car jumps and Hitler drops the gun. The Jewish guy picks it up and says, “Okay, now you eat it.” He runs home to his wife and says, “Honey, you’ll never guess who I had lunch with today!”

The film moves, it doesn’t just stay in anger. Anger is the release. The last image of the film is a text which mirrors the beginning text-on-screen: “SOB/S.O.B.” It says: I forgive myself. I forgive you. Maybe only in forgiving will I be able to let go, and be freed from the bonds of the past. I don’t know if I’m there yet!

Mike: Most of your work in the nineties is characterized by a very gestural camera style reminiscent of abstract expressionism.

Barbara: I want each film to accumulate in the viewer as experience, and later you can reflect on its particular images. Each experimental film creates its own diction which the viewer has to pick up on, figure out what language they’re in. Learning this language is the key to understanding experimental film, it’s what viewing entails.

My shooting doesn’t hold onto its subject, or study it. Instead the experience flickers past in light and dark and energy. I’ve been searching for ways to move the image, not to deny its specific meaning, but to add to it, and make equivalences. There might be shots of flames and leaves fluttering and water splashing, but because of the camera movement you experience them in an equivalent way. We apprehend the world bodily. This kind of camera work is less about composition, than about an embodied seeing, a felt perception. The images register experience between abstraction and representation. The camera glimpses. Time passes, it’s elusive and can’t be held. The camera sort of swipes at the subject, takes stabs at, approximates.

Mike: Tell me about midst (70 minutes silent 1997).

Barbara: midst is about seeing and light as energy. It was a reaction to the previous two films. I wanted to focus more on the formal or material properties of film.

Mike: Why is that valuable?

Barbara: It may be important, even desirable, after the period of political work that’s been championed. Art dealing with presence and seeing has been ignored. Abstraction has been considered self-indulgent or old-fashioned. But our understanding is deeper than language. For me it’s not either/or.

Mike: The film is silent.

Barbara: That came partly out of my appreciation as a viewer of Brakhage’s silent films, these beams of light connecting viewers directly and powerfully to the screen. Language activates a different part of the mind, it distances you from the image. So I decided in midst to trust the images alone. Virginia Woolf made wonderful books, but they don’t have to be in my film!

Mike: How did you structure the film?

Barbara: One basis is an art history of colour and perception revisited through film and video. It begins with a painter speaking. Though we don’t hear the words, we see his hands moving, and his work. Then he paints directly on film, showing three primary colours on clear leader. The following section acts out Goethe’s colour theory. He says that the red robes of a Cardinal will appear differently in sunlight and shadow, it washes out or darkens. Seen against different backgrounds, even the same swatch of material changes. Is the colour objective or subjective? How do we know red? Memory tinges events, images fade. Our perception of the world shifts with our frame of reference, when seen through different filters, different lights. The world accumulates meaning through this multiplicity.

The mid-section of the film is the most abstract. I was thinking of Cezanne, father of abstraction, whose landscapes were composed of patches of related colours. I shot farm fields in super-8, then, at the Experimental Television Centre in New York, added new colours to the footage, artificial colours that don’t exist except in video circuitry. The frame is fragmented with multiple images forming an abstracted landscape which vibrate and pulse with light.

Then the film moves to the beach with repeating shots in changing (video) colours. Repetition is a feature in all my films because it’s how we experience life. Each summer suggests summers past, all summers. The minute you dive into the water it’s like every time that’s ever happened. There are kids playing in the water, a close-up of hands rubbing, a woman swimming. Many find the woman swimming entrancing, calming… It’s here the film comes out of its abstracted self into a more emotional or narrative mode. Finally the video passages end and turn into film. We see flowers, bright vibrant colours in a flicking camera motion, so you just have to be present with it. There’s nothing to think about, you’re just with this liveliness.

The film ends in black and white, as it began. White is all light, black is the absence of light. The imagery shows superimposed waves on a beach and then a man’s chest breathing. Sources of life. How can we say where we stop and the world begins? Breath connects us physically — the space in us to the space outside — doesn’t it?

As usual I had trouble with the title! At one point Rae Davis suggested “Belonging” which fit, but perhaps told people how they were supposed to see the film. The word “midst” came from Agnes Martin, a minimalist painter whose writings I relate to strongly. One of her essays was called “In the midst of reality responding with joy.” Hence midst. In the middle temporally and spatially. In it, not looking on from a distance. Contiguity. Connectedness. Silence.

Mike: Tell me about C’est La Vie (10 minutes 1996).

Barbara: Increasingly, my films are made out of footage I already have. I almost don’t need to shoot anymore, whenever I think of something I already have an image of it. I have a bank of images at home which for now at least are enough. The man running down the road, or the man walking against the wind is our struggle, our daily lives, our doing of something while we’re here. It doesn’t matter if you’re a truck driver or an artist or a welder.

C’est La Vie begins with a series of still photos taken on the beach. There’s an old couple, a dog, and someone’s footsteps, and ripples on the sand which evidences the action of wind and water, the passage of time and repetition. There’s a woman dancer turning, and then meteorological footage of the world rotating. There’s also darker images of bats in a cave and animal bones lying out in the sun. And there’s a swan, its huge wings slowly and powerfully moving up and down. During take-off there’s a mad kicking and flapping before it moves serenely through it all. One day I watched birds pecking and it dawned on me that they’re not thinking. They’re just eating. Pecking. That’s it. There’s no mystery to solve, it’s all right there in front of us.

All of the footage was stuff I already had which I bleached afterwards. I took the workprint and put it in a tub of Javex which removes parts of the image. With colour film the top red dye layer is bleached away first, leaving the image green, if you leave it in longer the second dye layer bleaches away and you get yellow. Black and white footage becomes fragmented and harder to see. This obscuring and tearing apart is how the world is, it’s not just laid out for us, you have to look through it to see where you are. So the movement over the surface of the film is as much its subject as anything shown. It also unifies the diverse footage.

Mike: Tell me about Awake (3 minutes super-8 1997).

Barbara: The soundtrack is from Gertrude Stein’s Making of Americans, I excerpted a passage on aging and disillusionment, which Stein doesn’t see as negative. Being old means understanding that no one will ever understand or agree with you completely. When you’re younger it’s different. You try and fail, but age brings the knowledge of how things really are. Her text is read as voice-over and mixed with sounds taken from a girl’s track and field meet. You hear the crowd urging on the racers, the screams to win, to participate in the race that life’s become. Stein’s text, by contrast, is reflective and internal, awake to what reality is, instead of being a sleepwalker.

It’s all edited in-camera and shot in my bedroom. It shows a light bulb, curtains, and the television is on. My company. The camera allowed me to rewind and make superimpositions, so the pans in my room are seen at the same time as tree branches and a series of titles: “win win win” and “time space.” The superimposition in sound and picture show layers of reality, different times which converge on the mind.

My new film is called Like A Dream That Vanishes (40 minutes 1999). The title is from a Jewish prayer which likens our lives to grass that withers, or dust, or fleeting shadows, a whole string of ephemeral things, and the last one is “as a dream that vanishes.” The kind of shooting I do expresses the ephemeral nature of events. We get a little bit and then it’s gone. I wanted to make a film entirely out of leader. There would be bits of colour, with maybe a frame of an image, just these little splashes of colour at the end of a roll. But of course it didn’t end up that way. I think I keep making films because I’ve yet to make the one I see inside.

I wanted to create a visual space that would blur distinctions and boundaries. To move between form and formlessness, creation and dissolution. To conjure this place of dis/appearance, I wanted to use the beginning and ends of camera rolls where the image emerges from or dissolves back into pure light. I think of the emulsion of film as analogous to the ‘stuff’ or sea of life.

While I was working on this film, I met Rae Davis’s husband, John, a retired philosophy professor. To make overt the philosophical interests that have been below the surface in a lot of my work, I decided to interview him. He begins with Hume and the question of miracles. Is human testimony sufficient to prove the miracle of Christ rising from the dead, for instance? Then he describes the use of language in our attempts at making meaning, which leads him to Goertl’s Incompleteness Theory. This theory accepts that truths can be provable but contradictory, it’s an almost irrational position.

The film alternates between quick snippets of fast camera and blur and coloured leader and sync sound passages of John sitting in a chair. Out of this leader emerges something like a narrative, a chronology. You see a young child, then a four year old running and falling, which might be read as “the fall into the world.” Then people on a ferry (the ark — if you stretch), adolescents on a porch hanging out, jabbing, poking, drinking. Then individuals doing daily things, a woman combing her hair, contemplative, aware of herself. There’s a sax player, a girl alone on a bridge, a guy playing tennis. All of these images are the lived drama of the world. While shooting, I was thinking of Shakespeare’s seven stages of man.

All the world’s a stage

And all the men and women, merely players

that have their exits and their entrances

and one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first the infant

Mewling, and puking in the nurse’s arms…

Last scene of all,

that ends this strange eventful history

Is second childishness, and mere oblivion

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

By the end of the film, John’s speaking and the gestural footage draw together. He suggests that philosophy has returned to its roots in wonder and adds, “The world isn’t a very tidy place. We think it is, but it isn’t. It’s a very messy place.” And then he laughs.

Transitions (1991)

In 1986 Yvonne Rainer presented her feature length fringe opus Privilege to packed houses across North America. When floored audiences asked why they had never seen movies about menopause before, Rainer replied that the fringe had been the province of the young for as long as she could remember, and its traditional subjects—sex, perception and memory—simply reflected the age of its makers. In Canada there are fewer than a dozen filmers who are still making work past the age of fourty. Day jobs, family, and spiraling costs have contributed to this frightful attrition, alongside the failure of the fringe to find a home in the art world and its institutional supports. Simply put: as one grows older there are more reasons not to continue making than to endure. Many who have managed to maintain owe something to the work of Barbara Sternberg, a tireless champion of the fringe. She helped co-found Pleasure Dome, worked as the experimental film officer at the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre, was one of the key organizers of Toronto’s experimental film congress in 1989, as well as teaching, organizing tours and lectures. And for the past twenty years she has been steadily producing her own work, unique in its blend of myth making and diary address.

Born in the Maritimes, she came to Toronto in 1972 to study film before moving back east in an effort to unlearn much of what her education had imparted. She began work on a number of small, incidental exercises, which eventually included a trip to the local foundry. This watch over the local workers became the subject of her first public film Opus 40 (1979). Working in a more personal vein, she completed Transitions (1982), which details the sleepless imaginings of a woman. In 1984 she moved back to Toronto for good, began her organizing efforts on behalf of the fringe, and made a series of archetypal autobiographies. Characterized by an off-centered, anti-spectacle photography, her painstakingly crafted films take up issues of labour, love, and exile. While her work is informed by feminist sensibilities, its address is particularly aimed at men, who form both the subject and object of her work. Rendered in a rough schema, Opus 40 takes aim at the father; A Trilogy, the son; and At Present, the lover. In each of these films she pictures the essential isolation of her male subjects, and relates them, via montage, to the larger realms of the symbolic.

Opus 40 (18 minutes 1979) is Sternberg’s first publicly released work, her earlier makings withheld in a gesture of restraint rare in a medium whose makers typically include even the most elementary efforts in their public presentations. Set in a New Brunswick foundry, the film looks on as the men perform simple and repetitious gestures that forge oven parts. Their movements are treated as a series of themes and variations, Sternberg introduces colour overlays and split screens which echo the repeated gestures of the workers. Photographed entirely in super-8, Opus 40 (the title derives from a fourty hour work week) is at once a documentary on labour and a meditation on repetition.

Opus opens and closes with the grain of the voice, its nameless workers responding to the filmmaker’s questions about repetition. Two foundries exist, both aimed at the manufacture of stove parts, but the newer one is more mechanized, lending the workers in the old foundry a renewed sense of self-satisfaction. Alongside Sternberg’s admiring look at the bodies of men at work walks the ghost of Gertrud Stein, whose insistence on the importance of repetition and twice-told tales lends a solemnity to these proceedings.

Transitions (10 minutes 1982) pictures a woman dressed in white caught between “asleep and awake.” The restless insomniac never wanders far from her bedside perch, a linen enclosure which fails to ease her troubled reflections. The bed is drawn in the same white cast of its occupant, and together they constitute an arena of projection, a blank scrim on which the filmmaker inscribes the dreams of her protagonist. A flow of images passes over her—storms of insects and ocean waves, freight trains and fauna. Some of these moments caught in passing—like the seascapes and trams—are themselves metaphors for a mind let loose, rushing past the gates of reason. Elsewhere moments of narrative appear, as she dines with a lover, walks with him on the beach, turns to look at him. If these moments never last for long, perhaps it is because they are too painful to be recalled, and in their place an onslaught of metaphors ensue, each crawling with the horrors of division.

Her waking dreams are accompanied by a double-mouthed whisper on the soundtrack—the first offering philosophical expressions about time, repetition, and memory, the second marked by a more personal imperative, speaking of the demands of her mother and her husband. She is somewhere between them, between a dutiful daughter and a willing partner, between asleep and awake. Befitting its circular, psychodramatic form, Transitions refuses narrative closure, choosing instead to add light to the image until the screen glows in blankness, its white sheen the sum of all possible images, but also the white on which another night’s restless solitude may be repeated.

In 1986 Sternberg completed A Trilogy (43 minutes 1985), a moving and complex work which philosophically narrates the separation of mother and son. Composed of a number of apparently discrete elements, the film draws them together in a masterful weave of archaic ritual, home movie, dramatic interlude, and speculative address. At the heart of this intertextual weave is the filmmaker herself and her teenage son, Arlen. As he reaches the age of consent and prepares to make his final deposition of leave-taking, the film turns towards a reminder of all that has passed between them, and hints at what might lie ahead.

Throughout the film, the son’s movements are invariably those of traversal. Whether rolling over hills, racing across streets, plains, or seashores, he turns the landscape into an ecstatic shock of light and dark as the camera tracks his restless navigations. On the soundtrack, mother and son exchange letters—he has been sent to boarding school—and both begin to write in place of touching, detailing the events of their newly separate lives. Between past and present something has divided them, evidenced as much by Sternberg’s moving re-readings of a letter that is never a correspondence, as by the awkward school uniforms of a son which tailors a unity of purpose his movements continue to betray. This time apart, this distance between them, is interrupted by the filmmaker’s school visits, amply in evidence here because of the central place accorded the camera in mediating the distance between them. Then the film returns again to England in a multi-layered explosion of elemental fury and home movie pyrotechnics. As the boy climbs the English heath, volcanoes open and spit fire; images from other sequences in the film, slowly introduced and repeated over the course of A Trilogy‘s forty-three minutes, re-emerge here in new formations. As in a musical composition, Sternberg gathers phrases and motifs and plays them in different combinations. She is never content, like the chorus in a pop song, simply to replay the same theme over, but makes an image of memory itself, which she suggests emerges from this weave of associations, these fragments of lost days. The young boy looks out to answer his own watch ten years on, a woman’s pregnant torso turns in darkness, and in a hospital room a boy is being born, his umbilical cord cut by doctors. This section draws together all of the separate themes of the film using superimpositions as a metaphor for memory. As these images continue to recycle and recirculate, Sternberg turns to her closing text—a last scroll of intertitles filled with questions about being, time, and memory.

If the men in A Trilogy never lose their way, Sternberg suggests that this progression is accomplished only in the act that forgets the mother. Their amnesia impels the rational progressions of a positivistic science and its mythologies of objectivity, progress and the unmoved observer. A Trilogy carries on a dialogue with men from a distinctly maternal perspective, asking that they remember the stories of their youth, stories too quickly left behind in pursuit of a future they imagine to be different from the present, but which slowly turns to reveal the same face and the same understanding.

Double exposure was a technique of silent movies that saw itself as the translation into images of the theatrical aside. Destined to reveal their thoughts and feelings, it makes the face of the stars seen in fixed close-up even more inhuman, literally pierced by battle—landscapes, sea, sky, roads, unclaimed elements… but finally this process reproduces the visual sensation you feel at day’s end, when, during a trip, you look at your own reflection or that of another in the train or automobile window, traversed by the tumult of a landscape fleeing like an arrow. Double exposure will significantly be replaced by the travelling shot, realized from a moving automobile. Paul Virilio, The Aesthetics of Disappearance

A period of four years separates A Trilogy from Sternberg’s next effort—Tending Towards the Horizontal (32 minutes 1989). After the screenings and publicity which followed A Trilogy‘s release, Sternberg enjoyed an unprecedented exposure, marking her beginnings as a “public” filmmaker. Negotiating this scrutiny for the first time, Sternberg worked to banish the eyes of her audience from the very personal working methods she had been nurturing since leaving film school. The result is the most hermetically withdrawn and ambitious of all her film work. Its project aims to revoke the place of cinematic representation altogether, passing over the simply visible in favour of a presentness which can never finally be pictured. Tending Towards the Horizontal is a half-hour road movie, largely shot from a car passing through Toronto’s middle-class neighbourhoods. These solemn enclosures of brick and mortar are interrupted by momentary glimpses of a body at play, rolling and tumbling through the obligatory crimson tide which heralds the opening and closing of each film roll, the emulsion turning a bright red in the flush of sunlight that greets a camera’s opening. The spare accompanying track consists of a single voice, author Frances Daigle narrating three stories written in response to the film’s passage of domestic architectures. They are stories of wandering and transition, images of a world in flight inscribed in Daigle’s French-inflected monotone.

If Tending‘s catalogue of dwellings points to its origins in documentary, it is a documentary of consciousness. Sternberg aims to short-circuit the signifying practice which marries an object to its representation; her nomadology disarms the image, draining it of historical specificity and narrative circumstance. Tending‘s marriage of housing tracts and blankly delivered voice-over crafts a veil which is solemnly and insistently lifted to reveal the filmmaker’s Judaic origins, rootless wanderings through a landscape of exile. Cast into the waning light of the magic hour, we are asked to join her in a directionless walk, to enter into a history which can leave no traces and no reminders because it is time itself which has vanished here. Tending ‘works’ in a manner not unlike throwing a light switch in a darkened interior—for a moment everything appears slightly brighter than it really is, the world glimpsed with a profound attention and awareness. While most films are intent on creating a world for their viewers to inhabit, Tending instead asks us to return to our own.

At Present (18 minutes 1991) is Sternberg’s reaction to a male-dominated Toronto film scene. Especially incensed by its naked female subjects, Sternberg responded by framing her cast in isolation while a retinue of male suitors talk about love in a series of voice-overs. Each seems caught in that small circle of attention we call our personality. Her opening gambit wonderfully raises the stakes, exposing these small circles to the charge of history. Re-photographed from a Steenbeck screen, a screaming primeval man appears, his arms held aloft in an attitude of furious self-assertion. Though his mouth is open, the image is silent, its protagonist rendered mute. If its flickering rage reasserts its status as an image, it is also a reminder that we are watching an actor at work, painted and costumed to resemble our forbears. In a startling moment of juxtaposition, his silent cry is not answered by another ancient cry, but a contemporary architecture, a home which frames its male builder and resident. Peering out from a modern day enclosure, his smile assumes a dialogue and familiarity with his antecedent, as if our restless overturning of appearance had done little to change our understandings. Here Sternberg suggests that history possesses a circular shape which inevitably informs the passages of the present.

After this prelude we watch a quartet of sitters, each rendered in isolation. Photographed in a pervasive natural light, they perform a variety of domestic tasks—potting plants, sweeping floors, and rolling cigarettes. The film’s trajectory moves from inside to out, from home interiors to a natural setting which finally de-emphasizes the differences of gender. In order to fuel this progression, the filmmaker invokes a primal fire. It is a torch of memorial and of castigation, brandished initially against images of naked men caught in solitary states of arousal, this fiery storm a frank rejection of their alienated sexuality. The fire returns in a field-burning ceremony that destroys a rotting old growth to make way for new crops. The fire that is purgative and restorative is like Derrida’s pharmakon—both poison and remedy. The film closes with a shot that echoes its opening image—an old man (Sternberg’s father) sits before the camera, staring speechless into the lens before breaking into a smile. Suffused with natural light, Sternberg’s photo essay gathers images from an astonishing variety of circumstances and interweaves them with rare skill. These documentary vignettes are witness to the image of a new understanding, raised in a reinvented soil of communion and celebration. Her perspective throughout is resolutely maternal, bent on rejoining her solitary heroes with histories too easily left behind.