There are so many movies I want to make.

JM

She was Josie, José, Josepina, Josephine Maria Massarella, Hamilton’s favourite fringe movie artist, a filmmaker’s filmmaker. Supermom, daughter, sister. Her work was precise and immaculate, born inside the 80s dream that alternative cinemas would surely sweep away Hollywood and its imitators. Staunchly feminist, she filled her frames with women first of all. She was always behind her own camera, chasing the silvery dream of film even after most of the labs had shuttered their doors. She died quickly and suddenly in the spring of 2018, after a hospital stint that allowed a bevy of family and friends to stand at her bedside, the steady flow a testimony to how much love she had inspired.

How to speak of her complications? Her joys and struggles? When she is no longer able to say the words for herself.

Felix Werth: My mother was born in Fondi, Italy on March 12, 1957. She crossed the Atlantic Ocean as a baby in her mother’s arms.

Dana Randall (George): They were on a cruise ship and my mom was seasick a lot. So my dad and my 9-month-old sister toured the ship. She was walking and toilet trained, already drinking from a cup. Fully formed. When they got to Canada my aunt showed up with Benny who was two-and-a-half, still in diapers with a bottle, and Josephine looked at him and asked my mother, “Why is he still in a diaper?” She was born running.

Charlotte Disher: That was true of her filmmaking too.

Dana: My father came here as a tailor, my mom was a fashion designer. My father saw that Canadians could buy suits off the rack, they didn’t need handmade suits, so he became a mason working with ceramics and marble. My mom worked in a sweatshop. Their idea was to become fashion designers and go to Rome. Instead my mom sewed underwear bands while my father apprenticed as a mason.

When Josephine was 15, she chose to live in a foster home for a year, rather than with my parents. People like Josephine and our cousins Flora and Christine were girls born in Italy, and when they came to Canada it was not a good time for them. Everything you did was scrutinized. If one uncle thought your skirt was too short he’d walk over and talk to your parents. The way you walked, what you said, who you were talking with. Josephine was the oldest so she paved the way for the rest of us.

Charlotte: They had to fight to get what they wanted.

Dana: They all married young to get out of the house. Craig came up to her and started chatting with her. There wasn’t anything happening, but someone saw her, and my parents found out and they were terrified. It was really bad. I remember my parents hitting my sister. Though sometimes our parents were the least of our worries, because if I was being bad I would get hit by my aunt, possibly by my uncle, and then if my parents found out I would get disciplined again.

They were terrified of being in Canada. You have to watch what you say and do or the immigrant office will deport you. Back in Italy, my mom used to get in trouble all the time, she was a wild child. I think Josephine was more like my mom than she would care to admit. This was on Lock Street in Hamilton, near Main and King on the mountain. The neighbourhood was 90% Italian and the Red Devils motorcycle gang lived across the street.

She married her first husband Craig Patterson at 18. When she was 19 they sold everything they had, packed their bags and moved to Vancouver. We thought they were a couple, but they’d broken up. She came back a year or two later for Christmas and finally told us.

Felix: She moved to Montreal to study Italian and French at the University of Montreal for a couple of years. Later she joined the University of British Colombia Film Society, where she discovered a love for film that shaped her life. It was here that she met my father Michael Werth who was studying engineering, though he soon switched his major and entered the film program.

Dana: My mom was three years older than my dad. I’m older than my husband. My daughter’s dating someone younger. And Josie was older than Michael.

Charlotte: He was 18 when they met, and I remember her going on and on about how beautiful he was.

Dana: He had that long flowing hair. We called him Fabio (laughs). They got married on her 30th birthday, he was 22.

Charlotte: Michael asked her to marry him every year.

Dana: We were stunned when she said she was going to film school. She was months away from graduating in French. How do you propose to pay the bills? She didn’t tell my parents until she’d finished two years of film school.

Michael Werth: The film department at the University of British Columbia was pretty Hollywood-centric. Experimental filmmaking was not on the radar. We became exposed to the masters of that genre through the Pacific Cinematheque and the Western Front showed videos that grappled with sexuality and politics.

There were 12 people in the class, and 3 were picked to make films. Josie’s movies were never chosen. But grants and equipment were available through the Film Society, and that allowed Josie to make films like Cold City for Street Artists. It was a psychodrama starring Jill Daum, who is now a well-known Canadian playwright. She was the girlfriend of Maurice who had a band called Maurice and the Cliches. We got involved in shooting a video for them, and that’s how we met Jill. In the film Jill isn’t happy with her arrogant boyfriend and has horrific visions — nuns tranform into hags with melting faces, and there are a lot of severed heads. I don’t think she considered it her best work.

Cathy Ord: In 1983 she asked if I would be in her film Doctor’s Orders, although I remember it as One Woman Walking. I had to walk all over Vancouver and we wound up at the beach. She liked my walk, she said it looked strong and forceful. She was looking for a strong woman to be the background for her voice-over about the relationship between women and doctors. It was about women taking control of our own bodies. We shot it in an afternoon, on one of those rainy Vancouver days.

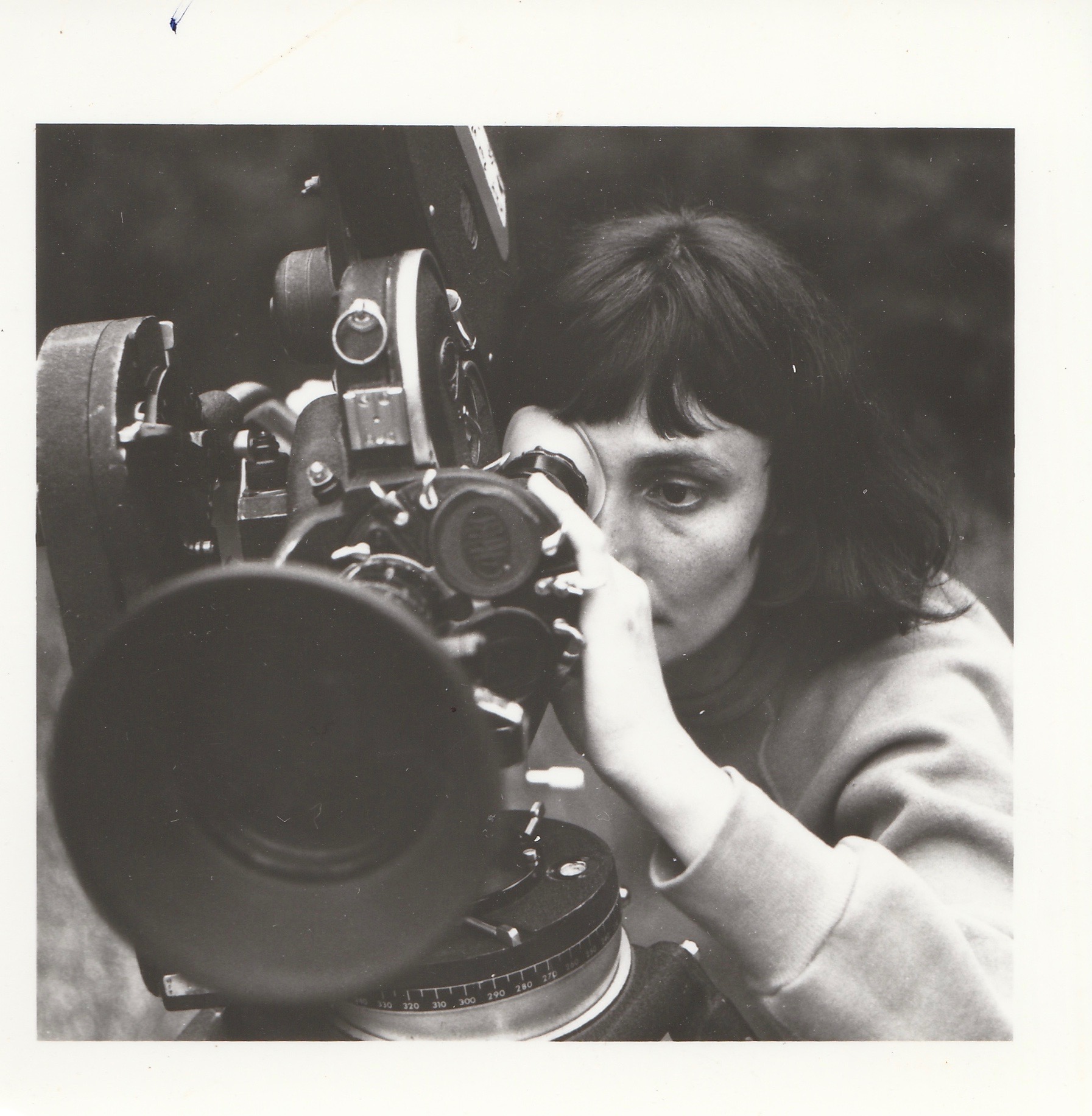

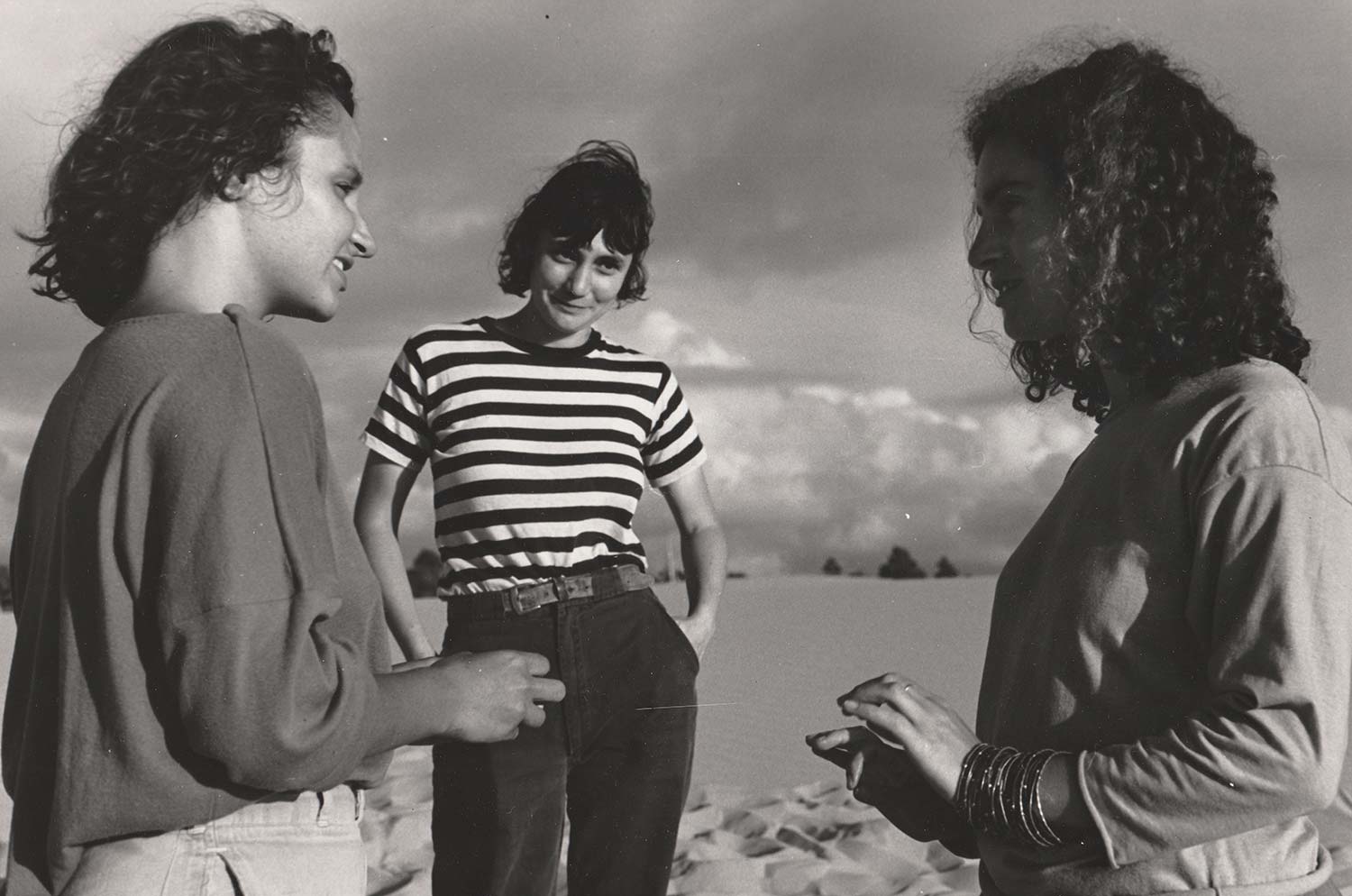

Mike: In 1984 she made One Woman Waiting (9 minutes 1984) on a single roll of film, and it travelled around the world announcing a new talent and vision.

Dana: Josephine shot One Woman Waiting twice. The first time was in Canada, but the light wasn’t perfect, and the second time they crossed the border into Oregon.

Michael: It’s about a woman who is a little lost, and then is found by another woman who is more confident, who embraces and encourages her. That was my interpretation anyway. We first tried to shoot it in on Deas Island with Moira McDonald and Maggie Buchanan, two school friends. They make cement there, so there were huge piles of sand, but the location didn’t look good enough, so months later, with different actors, Josie went to Lawrence, Oregon and reshot it. What you don’t see is that just offscreen are dozens of dune buggies screaming around the thousands of acres of dunes in that park. I don’t know how they managed to keep the sand clear but as I recall it took several days to get that one shot and there was only one other take which was basically a throwaway. I think the crew of four women really puzzled the ATVers who found them in the middle of the dunes with a camera but no vehicle.

Dana: She brought the film home to us, a very Italian immigrant family, and we see a woman waiting in the desert, and we’re waiting, and then another woman arrives and relieves her of her post. Josie asked us: what do you think? We all just stared at her. We didn’t get it. She was living in a different world than us. My parents were still afraid that someone was going to call the police because we weren’t acting “Canadian.”

Michael: In No.5 Reversal (10 minutes 1989) there is a reversal in mood, from pillow talk to memories of counter-revolutionary slaughter in Nicaragua. Along the way images of peace, nature and familial love are juxtaposed with zones of destruction. The question is why? I think it was partly a statement of the artist’s struggle — to engage with the reality and horror of life but also to show and remember how beautiful life is, how water keeps washing away the blood of our human mess.

Charlotte: It starts and ends with two women in bed talking, but we don’t hear their conversation. Instead, we hear an upbeat song.

Michael: The Ruth Brown song was on a compilation album we owned, and we had never heard of her before, so Josie just located her and over the phone (and later on paper of course) Ruth agreed to let Josie use the track. I think Josie liked the idea that it was such an upbeat track about sadness, and that played into the reversal idea.

Dana: For No. 5 Reversal she wanted to shoot in Niagara Falls. It was the coldest night of the year but she insisted. We drove down in (my husband) George’s truck, and it was so cold we put the film in our coats to keep it warm. We could only shoot for a few seconds at a time. I couldn’t feel my hands. Josie had her gloves off and her hands were blue.

Michael: In No.5 and in One Woman Waiting, Josie celebrated the relationship women have with each other. I think she was trying to create characters but without using dialogue, and was ahead of the curve on the Bechdel test.

Felix: As a feminist she placed women first, both in front of and behind the camera, and fought against the objectification that sadly still dominates the media.

Dana: We grew up in a society where men ruled. But my mom was the ruler in our house. In mixed company she always gave my father the floor, he was the man of the house. But when we were disciplined, we were more afraid of my mom. All the women in our family were dominant.

Charlotte: Interference (20 minutes 1990) was shot in their (Josie and Michael’s) apartment. I set up lights and carried equipment. The woman in the film is supposed to be writing. But she does everything except, she procrastinates, she goes downstairs and checks the mail, she looks out the window. It was shot at Bathurst and Eglinton. Josie converted their bedroom into the office of the woman in the film. She would shoot the same scene over and over again just to get ten seconds of something perfect.

Dana: At the very end I come in and say “Hi, how was your day?” Josie was always behind the camera. Michael would have been doing the sound. Charlotte was always there. If you weren’t an actor you were doing something else. There was always tons of food and wine.

Michael: I can see her love of Chantal Akerman, Maya Deren, and Jacques Tati in this film. It was shot in our apartment where she wanted to celebrate a character who doesn’t really do anything important. Not an unsung hero, but an everyday person. It was shot mostly without sound, and the entire foley track was recorded wild on location, and edited later with a few layers of offscreen effects including some ethereal train shunting sounds.

Charlotte: For Green Dream (23 minutes 1994) she collected footage without knowing how it was going to be used exactly.

Michael: I don’t think it was pre-scripted but grew “organically,” informed by feminism, paganism, eco-spirituality… not to stick too many labels on it.

Charlotte: She filmed in southern Ontario conservation areas, waterfalls, Devil’s Gorge. If she had a choice she would always be filming. It was hard lugging around all of her equipment (she had a large wooden Sachler tripod), especially in the winter with all that snow. Years later, she kept returning to those areas.

Michael: Until the late 90s I was basically the crew. I maintained the equipment, charged the batteries, loaded mags, carried tripods, drove the car, took light readings, did assistant camera, some optical printing, all that kind of stuff. In between travelling on shoots I was working as an editor in the mainstream industry.

Felix: Her unique vision, inspired by Italian filmmakers like Michelangelo Antonioni and early experimental filmmaker Maya Deren, was respected, admired and even loved by the mostly macho cinematographers of her time, who praised her beautiful and often breathtaking images.

Michael: I think it was important to her that her films did not speak with a simple voice. This was not for the purpose of showing off — how smart am I, that you can’t figure out my film — but rather that the meditative images created moods that stirred an emotional response, that opened little parts of your mind, letting you feel what you felt, not telling you “this is how I feel and I want you to feel the same way.” There wasn’t usually a prescriptive voice in her films

Celeste Sansregret: Nightstream (12 minutes 1996) was based on a dream she had before Felix was born about being pregnant. She told me I was playing a fertility goddess.

Felix: My mother had a huge sense of the absurd, inherited from my grandfather and inherited by me. She saw the humour and the ridiculous in almost everything.

Celeste: We drove out to the Elephant Hills on a hot, sunny day, leaving in the early morning. I had a lot of experience as a stage actor, but it was the first time acting in a film. When we found the spot she wanted to shoot she surrounded me with cowrie shells — a fertility symbol. Josie was behind the camera (there was no sound), and shot from different angles. She asked me to look directly into the camera, and think about certain things, knowing they would show on my face.

Edie Steiner: It was a freezing day when Josie filmed my scene of Nightstream. She needed a pristine, snow-covered field, which we covered in red apples. Josie was always meticulous about her shots and we had to toss the apples into the frame without disturbing the snow where they landed. My character was one of several women filmed in a variety of landscapes and seasons.

Felix: Her friend Edie Steiner used to teach screenwriting at Central Tech High School. When Edie didn’t want to continue, she recommended my mother, who eventually added a course in cinema studies.

She watched a feature film every day, her library cards were always maxed out with borrowed DVDs. She liked Chris Marker and early experimental work where the primary focus was the novelty of the camera. Witness starring Harrison Ford was a favourite.

Dana: When Josephine and Michael split up, she moved back in with my mom.

Charlotte: The break up was sudden. I advised her to leave him because she was pregnant and he didn’t want her to have the kid. He was younger and wasn’t ready for it. That’s why we ended our friendship. She became the victim and wouldn’t leave him. It wasn’t a good place for her to be.

Dana: But they had Felix, and Michael in the end was really happy. She was 35 when Felix was born. That’s when I started seeing the change in my sister. We used to go into Toronto and sleep on the freezing cold floor in whatever warehouse they lived in while they worked 24 hours a day. Then she had Felix and moved to Coleridge where she lined her whole house with that piping you put around sharp edges. She “baby proofed” her entire house! We said: Josephine, what are you doing? Kids are pretty resilient. They can eat dirt. But she would follow him around in case he fell.

When Josephine had Felix, nothing else mattered. She went from being a working person to a stay-at-home mom. She was obsessed with Felix. He’s an amazing person, but it could have gone so differently. She never said no to him.

Jasmine: I dated Felix when I was 16, ten years ago. Josie was my second mom, I stayed at her house all the time. My parents were really strict and she would always lie to my parents for me. She knew I had no freedom. My parents would call the house and ask “Where’s Jasmine?” And Josie would say “I don’t know…” (laughs) She was so understanding.

There were thousands of meals. We’d go over at lunchtime from school, and she’d prepare a five-course meal, and then another for dinner. At the end of the day or night she’d drive me home. Felix and I are still best friends. We talk every day.

Charlotte: I was shocked when I found out that she’d stopped making films.

Dana: I was really surprised that she wasn’t making films.

Jasmine: When I first met her she wasn’t too active with filmmaking. But as Felix grew older and more independent she started again.

Mike: Impossibly, Josie conjured a second life as an artist. After her first 5 (public) movies, 17 years were spent as a dedicated mother, sister and daughter, living in a shared house in Hamilton with her son Felix and her mother Gemma. And then she started making movies again, reunited with her Bolex, indestructible analog accompaniment. She finished three movies, all landscape riffs, the products of slow and careful observation, gathered during daytime hours when the light was also a dream.

Felix: I was happy to see her making things again and it was great to see her technical aptitude. I had seen her film gear ever since I was a child, but it just looked like cool toys that belonged to another world. I had no idea they were associated with her.

For Light Study (12:30 minutes 2013) my mother knew she wanted to shoot on the escarpment, in areas already familiar to her. She would go up to each location for 1-3 days and walk the trails with her equipment. I would go with her. In each spot she would shoot for hours, often a frame at a time. It took three years. Our walks were familiar because up until I was 14 we went for an hour-long walk every day.

Josie: Nature is a great inspiration for my work, inspiring reflection on our relationships with other life beings. Personal perspectives often point towards nature, and look upon it with feelings of humility, reverence, and respect. Light Study speaks to this, infused with a plethora of waterfalls, lakes, and wetlands, a poetic examination of the ecosystems along the Bruce Trail.

The film opens with an ancient waterfall, and ends on a glass-like surface of a thriving marshland. Sparkling emerald waters, and sun-bleached rock faces intersperse with animate life forms flickering across the screen. Here, nature presides over an ephemeral human element, its primordial essence both medium and agent of light’s eternal change.

Felix: She didn’t have a proper editing set up. She worked with sheets of paper, looking through the film frame-by-frame and writing down the edge numbers where she would make her cuts. Then she would get the film digitized and call Boyd Bonitzke who worked on the colour correction and the finishing.

Boyd: Light Study was a purely single-frame 16mm film. When she came to me, she’d already had it digitized, though she couldn’t get anyone in town to do it; she had to send the film to New York. Typically you optimize each camera start in the transfer, but in this instance, every frame was different, so the lab had little choice but to digitize it all at a single, average setting. It meant doing a lot of extreme colour correction on our end, because the one-light transfer was so muddy. The editing per se was Josie’s work, even though she wouldn’t take credit.

She had gathered the footage in conservation areas over several summers. There was lots of painstaking work looking for the right plants and insects and birds and fish. Working single frame required hours of shooting. She would create entire sequences in-camera, many of which remained intact. In other cases she would slice out and rearrange single frames into new sequences in Final Cut.

Felix: As the title suggests, it was always intended to be a study, a collection of observations. Light was always the focus when she was looking for locations.

Dana: When Josephine moved in with our mother she lived rent-free and my mother paid all the expenses. We became enablers, she had no money at all. I would collect Shoppers points for her, but invariably she’d buy things for Felix. We all tried to take care of her. We would tease Felix and say: you better get a really good job because someone’s going to have to look after your mom. As militant as she was about filmmaking, she was also militant about taking our mom to appointments, keeping her medications in line. She was invited to a festival but refused because she felt she had to look after our mother. It was a love-hate relationship. They knew how to press each other’s buttons.

Charlotte: I think she felt guilty about not having a job and living with her mother. It’s almost as if she regressed back to being…

Dana: A child.

Charlotte: In terms of living at home. But not in her filmmaking. She never compromised there.

Dana: It’s as if she had a double life.

Charlotte: I had a hard time tolerating the victim personality that came out.

Dana: She acted the victim part so well that she started to believe it.

Jasmine: She had a thing about wearing black all the time, she never wore colours.

Boyd: I asked her if she had ever worked in video, and she said she hadn’t. I urged her to try it. I suggested she run through the list of projects she had in the back of her mind, find something short and manageable, shoot it on video, and see how she liked it. That’s how she made No End. She appreciated the freedom it gave her, the possibility of doing virtually unlimited takes, the ease of image manipulation.

Felix: No End (5:57 minutes 2013) was the only movie Josie shot digitally. She wasn’t working a frame at a time, as she did for many other works. In fact, she was still familiarizing herself with the camera, which was rented from LIFT, the film equipment co-op, and after this movie, she never used it again. Her money was tight so she didn’t actually pay for the camera, she volunteered at the co-op, and used her hours to buy time for the camera, one hour of volunteer time equals one hour of camera time. She did the same for the edit time she needed.

She shot between six to ten days on the project, and I would go with her. She knew the locations she wanted to visit, and had clear ideas about the overall shape of the movie.

Josie: I believe my films have a poetic, impressionistic quality, often challenging the viewer with an eco-aesthetic viewing experience. No End was given its backbone through poetry and its supporting structure through nature. It was inspired by a poem I wrote over the course of six months. What developed was a lyrical journey exploring the interconnectivity of lived experience, with images dancing across vistas of ancient rock and waterfalls, old forests and spanning skies, speaking to me of time, evolution, and dissolution.

Boyd: She went through all the footage and wrote out preferred takes and then we assembled it from her notes.

Mike: In No End a young woman wanders through the landscape, which is powerfully felt and framed. A suite of superimposed titles appear: “burying the burden of grief… releasing all remembrances of you.” It seems her onscreen avatar has arrived both to remember and to let go, to hold and release.

Felix: It started after her brother Vince died of cancer, which he’d been struggling with for eighteen years.

Dana: Vince had cancer four different times. They misdiagnosed the first two. Then he did a stem cell transplant with his own stem cells. He finally tested cancer free, but it turned out there was a hidden blood cancer. When he went in the fourth time he just gave up. He was tired. Both he and Josephine had rare cancers.

Charlotte: It could have been about the loss of her marriage, there was a lot of loss in her life.

Felix: I think the movie is about my father, their marriage ended when I was four or five, and my mother was never in another relationship.

Franci Duran: Josie had a sublime way of shaping light and time. She had a kind, encouraging word for everyone and an infectious laugh. I think of her often and miss our talks about art-making and the politics of exhibition, the pain of exclusion and joy of acceptance, of returning to practice, of claiming space as an older woman, of parenting.

Michael: 156708 (6:37 minutes 2017) was the model number of her Bolex.

Josie: I shot 165708 entirely in 16mm black and white film using single-frame photography, employing in-camera techniques and chemical manipulation of processed film to produce an eidetic study of temporal elasticity. I incorporated techniques like stop motion, time-lapse, light painting, flicker, tinting and toning. These techniques, combined with cycles of alternating exposed frames, imbue the work with a rhythmic magnetism, apparent both in the tempo and the aesthetic of the images. I’m particularly happy with the dynamic original score, composed by the acclaimed Graham Stewart.

Felix: She sometimes asked me questions about the edit, for instance, does the dissolve of Jasmine’s face to a shot of water have macabre implications? Is there a suggestion that she’s drowning? We talked a lot about the movie’s transitions, how it moves from one scene to the next.

Jasmine: She asked me to be in No End but I was going through a hard time so I couldn’t commit to it, but I had free time when she asked me again. She made it sound very casual. Would you mind shooting some scenes for my movie? You don’t have to talk. We would start in the morning and shoot until sunset. It was four full days with me, and many days shooting by herself. She kept telling me to pretend that water was disappearing, that the world was brittle and dry, so that’s what I was facing right now. She shot one frame at a time. There was lots of walking, turning my eyes and looking, everything I did had to be slow. We reshot each gesture 30 times.

Dana: She wanted a fire scene so we said come on over, we have a fire pit. We burned wood for four hours, and she’s just going on and on shooting with a Bolex. When we saw the movie, the fire lasted three seconds. I looked at her and said “Really?” But Josephine was like that, she’d make you redo it until it was right.

Josie: Another challenge is calculating the frame count for the alternating frame cycle technique. In order to calculate the sequence of frames, it’s important to know the length of the shot. Using a camera that allows single frame photography, such as a Bolex, I set the frame counter to zero. I then expose the first frame, write down the frame number, cover the lens, and advance the film one, two, or three frames (depending on the total number of images in my sequence). I then write down that frame number, remove the lens cap, and expose that frame, repeating the process until the first image sequence is complete. Finally, I repeat this entire process until all image sequences are complete.

Boyd: It was never a lot of work (my role in the editing) because of the nature of the films she made, shooting single frames in 16mm. She’s the only one who can edit that. She knows what she sees in her mind. Some of the footage for 156708 was optically printed, or hand-tinted or toned. I asked her, “Did you have to spend all that money? We could have done that digitally.” But she was in love with tactile processes. She felt it looked different.

Charlotte: I think she felt a lot of pressure to make films, that time was running out.

Dana: During the last year she really went downhill. To have one rare cancer is one thing, but three on top of each other… She had sarcoma and pinna, and then Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule.

Charlotte: Seeing Felix in the hospital… that was a really hard thing for him. He maintained his upbeat manner, teasing her relentlessly, right to the very end. Playing games with her, trying to keep her mood up, being silly. I know that helped Josie tremendously. Some relatives started crying hysterically, or stared her down, the Italian way. After the stroke we didn’t know how much she could understand, but she could still read emotions and body language.

I was there when Michael showed up at the hospital and she got a little bit weepy, I hadn’t seen her like that. We were worried what her reaction would be to seeing him again. Their relationship had become a little bit better. She reached out her hand and then they were holding hands and she was smiling at him. It was an incredible moment.

Dana: She always tried to encourage us to follow our more artistic paths. Our sister Mary wanted to be a writer, but became an accountant. Our brother Vincent played guitar and became an architect. I wrote poetry and wanted to sing and I’m in marketing. Josephine was the only one who followed what she wanted.

Jasmine: Her voice is so clear in my head. She’s still alive.

Boyd: She was very humble, reluctant to take credit for what she had achieved.

Charlotte: She refused to do anything else. She was single-minded and militant.

Dana: She asked me: don’t you want to do exactly what you love? And I said: not everyone gets that choice.

Charlotte: I missed years of her life and when she was in the hospital I apologized to her for that.

Dana: She always wanted to go out for coffee and I apologized for not making the time.

Charlotte: We all had a chance to say good-bye. And then she fucking died.

Dana: That’s just like her, right?

Charlotte: It just seems so crazy. I’m still on what I call the Josie diet, which started when she went into the hospital. Too much wine.