Kinodot: Nothing Else But This

An interview with Alena Koroleva by Yunglin Wang (June 20, 2019)

Published on Pleasure Dome website http://pdome.org/2019/destinations/

Yunglin: Kinodot Experimental Film Festival was launched in 2012. In the first two years it was an online minimalist short film festival in Saint Petersburg, Russia, then the festival started showing in different venues. How and why did you found Kinodot? How do you distinguish it from other film festivals?

Alena: Mikhail Zheleznikov and I started the fest in 2012. At that time we worked in the selection committee of Message to Man IFF. It is one of the biggest festivals in Russia with a focus on documentaries. Part of our job was to watch thousands of submissions, and sometimes we couldn’t find a place for interesting unusual low-budget works, they just couldn’t fit. So we decided to begin our own project. We were convinced that to make a good film you don’t need a lot of money, producers, big team, special education or fancy equipment, only a good idea. We believed that restrictions create freedom, and remain fascinated by the idea of simplicity. We invented four criteria, although each selection had to fulfil only one of them.

Yunglin: Can you talk about Kinodot’s four submission restrictions?

Alena:

1. No Money – films made without a budget.

2. No Mumbling – films without dialogue or narration.

3. No Music – films without a music score.

4. No Montage – films made without editing, made in one shot.

With these restrictions we wanted to show how we dream about the liberation of filmmaking from a dependence on money; excessive use of music, which sometimes is used as an easy way to manipulate feelings or create a “mood;” avoiding too much text is a way for cinematic language to thrive; and films made in one shot is just a beautiful idea. We don’t have anything against montage, we wanted only to emphasize the possibility of making a work in one take. Eventually we dropped these criteria in order to broaden our selection, but we still have them in mind and welcome minimalistic and low-budget productions. We had a great example of a one-shot movie in our last edition – Mr. Yellow Sweatshirt by Yoni Brook and Pacho Velez. It’s an allegory about someone lost in bureaucracy, it shows a man trying to enter a subway, but his card doesn’t work. The winning movie this year was by a student, Yung Lean, Please Be My Yung Love by Julia Mellen. It’s a love story told in Youtube era-style – made with very simple means: loose, casual, even messy, but at the same time honest and risky.

The first two editions of Kinodot took place in Erarta, a contemporary art museum, where we showed our programs as single-channel screenings. The program was also streamed online where viewers could vote for their favourite. We offered a money prize that was raised through submission fees.

In 2015 we presented our selection in Fligel, a courtyard with many adjoining spaces (galleries, cafes, bars, shops). We put one movie/monitor in each space and invited people to walk about and see the festival in their own way. In 2016 we changed our exhibition format because we felt the gallery experience wasn’t optimal for the works we were interested in. We found a Photo School that was willing to host screenings, a friendly place with an audience. We had a professional jury for the first time.

Our current selection remains a mix of films and visual art works created for galleries. But we decided to move our program completely into the theatre because when you sit in a dark room with others, even if a work is a bit difficult, you can dedicate your whole attention and see a movie from beginning to end. The theatre space creates a different perception of time, it allows you to go deep into a screen, there’s nothing else but this. Time is a plastic aspect of the medium itself, movies typically squeeze and stretch time. Every movie is a time machine. The theatre allows these expressions of time to be fully absorbed.

Yunglin: In 2012 I organised the Taiwan Video Art Biennale. There were 90 video works shown on 40 TVs and projectors in the museum. Due to this reason, I am curious about what you think about video artworks being selected to an experimental film festival, as well as the boundaries between experimental films and video art today?

Alena: Both film and video have their own histories and genealogies, their own family settings. But video art today offers a fantastical bouquet of styles and subjects. On the other hand, much of what passes for “experimental film” comes from a tradition where certain artists have been so overexposed that they have created the field of inquiry, and newer artists continue inside these lines, making formal, “apolitical” conservative materialist works. We try to keep our selection open to a wide variety of practises, and use the umbrella-term “experimental films” for all kinds of unconventional, genre-bending, time-based visual works.

Kinodot is an independent project, we run the festival without government subsidies or financial support. We operate on a small budget raised from submission fees, and this way we try to avoid any interference in our programming. While there is no official censorship in Russia, it has become more difficult to show films. A new law for film festivals copies the Chinese model where the government tries to control all public screenings. Recent years have been marked by repressions: journalists and artists jailed for fabricated cases, protests are supressed. Distributors and owners of cinema theaters sometimes cut and reject films just in case. We had to move one Kinodot screening into a bookstore, because cinema theatre owners didn’t want to show a film that showed Pussy Riot protests (We Make Couples by Mike Hoolboom). But so far we’ve been able to show all the films we wanted, one way or another.

Yunglin: In the “Destinations” program you presented with Pleasure Dome, works were selected from past editions of Kinodot. The main concept of the program is related to “home” and “identity” and derives from the concept of “bare life.” Could you elaborate on the curatorial concept?

Alena: In the last years we’ve presented shows entitled “Highlights from Kinodot,” but for the “Destinations” program I selected films that touched me personally. Some of the most sincere films I’ve discovered in recent years have related to home or are an attempt to recover lost roots. Like so many others I don’t have a home, I live a nomadic life, drifting between countries and cities, so the question of place feels generative. It’s an essential place to start for artists, to find a connection with the world, to find your main points of interest. To know who you are.

Displacement and political oppressions continue around the world. People lose their culture and language, their ancestral roots. To find this connection again is sometimes made possible through pictures. Every artist invents a different way to speak about it. But at the same time we share the necessity of this relationship.

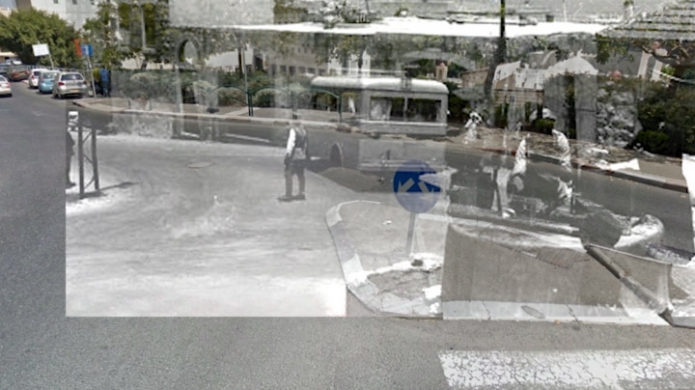

I wanted to show movies from around the world – from Africa, Asia, Middle East, Europe. We share a common hope and need: to be connected. For instance Your Father Was Born a 100 Years Old and So Was the Nakba was made by Razan AlSalah, a young Palestinian woman who uses Google Maps to return to the place where her grandmother used to live, at the seaside in Haifa. She can’t go back physically, she’s not allowed even to visit, this virtual passage is the only way she can see the neighbourhood of her ancestors. The pictures are filled with anger, all the Arabic names have been erased, replaced by new names and legends (liberation for who?). This film is a revolt against these erasures and the catastrophe of forgetting.