.jpg)

Two Cities

When I was in film school, there were only two real cities in America. The first of course was New York City, this was the place where all ideas came from. Everything that was fine, and everything that was not fine, could be traced back to some crack on the sidewalk, some starving artist’s hope scrawled on a late night, east side napkin. We knew, even as film students, that if our ideas were any good, they would have already occurred to someone in New York City. They were in a different time zone there, the time zone of the future, while we were stuck in the time zone of the ordinary present.

And the second great city of the United States? That of course was Ann Arbor, Michigan, which hosted the most important event in the cinematic universe, I’m speaking of course about the Ann Arbor Film Festival. And I’m not only speaking about the legendary green room orgies, the all night reefer sprees, the ageless staff that seemed to need not even a moment’s sleep during the festival’s hurricane of pictures. What impressed us about the Festival was that the most arcane and obscure and impossibly too long and bewildering movies and therefore the most important and significant moments of motion picture history (which was the only part of history we were interested in then) could actually be shown in a real movie theatre – the king and queen of movie theatres, as we thought of it then – the Michigan Theatre, with its velvet plush of 1700 seats.

And even though the movie that was being shown might be about, for instance, the colour red – “Oh, I’ve never seen something quite so red before, and certainly not for that long, imagine a sunrise that lasts all day” – everyone would come and take a seat. And take one of the 1700 seats. And the audience wouldn’t be young, wannabe avant garde hopefuls with bad haircuts and a right hand that permanently twitched if there wasn’t a beer to hold it down, no, no, these were real people, in fact, these were The People. This was The People coming home. This is how we spoke of it then: the garbage truck loaders, the plumbers and dry wallers and hardware store operators, the hair cutters and backroom leather men, they would all come to take their place in the brave new light of the darkness.

Science Fiction

You have to imagine this moment – while people all over the world were cueing up to see expensive American movies, here in Ann Arbor the future had already happened – or so it seemed to us Canadians, from the comfortable distance that the border afforded – you had already entered what we thought of as the next phase. We thought of experimental movies like sushi or thin crust pizza or vibrators or bike lanes, if people would only give it a taste, give it a try, they would leave behind the superheroes and action figures forever. And once the pictures changed, then everything would change.

The Ann Arbor Film Festival looked like science fiction to us, in part because of the movies, that looked like the future of cinema, but mostly because of you. Because you kept showing up, year after year, filling all these seats. And it seemed that you were showing up because of the most politically dangerous reason of all. The reason that would eventually undermine every CIA wet dream and imperial slaughter, or so we imagined at the time. When we came here for the first time, we looked at your faces in wonder, I have to admit it, we came for the movies, but we spent most of our time looking at you, looking at your slack jawed, open eyed faces, soaking in these difficult emulsions. Because what we saw confirmed out deepest hopes. That you had come for pleasure, and not out of duty. And armed those new pleasures, there was no doubt that we would bring down the Pentagon and arrest Sheriff Arpaio, we would end the remnants of slavery and the apartheid state hangovers. We would bring equality to every gender and invent three new ones, we would take politics back from the politicians and we would do it by legalizing everything that made us feel good. It was our pleasure that could no longer be contained, we would expand our pleasures until the system simply burst and collapsed. It was that simple, it was that complicated. We would watch these impossible movies, with their plotless ruminations on light, and we would learn to look into each other’s faces again, and find them more interesting than anything on television. We would broaden the spectrum of our joy and our love, and these movies would show us the way. They would demonstrate the secret life of trees, the infinity of a nose, the view out a window. They would vault us past the armour of our preferences, of our old standards of beauty, of what was acceptable, of our own moral orders, and it would make us soft and accepting, even when we faced the most difficult moments of our own lives. Especially when we faced the most difficult moments of our own lives. These movies challenged us to open and to keep on opening and to keep on loving, until we had untied every knot, until we had unearthed everything inside and outside of us that said no. Until we had lived every revolution.

Disappointment

What can I say? We were young. The Wizard of Oz lived in the Emerald City. But the Wizards of the avant-garde lived in Ann Arbor, specifically, in the Michigan Theatre, once each year, in the spring, when everything was beginning again.

So of course you must be wondering, I’m wondering myself – when we came here for the first time, were we disappointed? And of course we… and of course we… and of course we were not disappointed. We were too young, we hadn’t learned how to be disappointed. Disappointment is a mature pleasure, it’s a pleasure that belongs to adults.

With all those movies we didn’t understand, the crazy organist, the gi-normous screen, the steady thrum of crowds, the oversalted popcorn, we fell into a sleepless swoon.

Arrival

I came with a scrum of fellow travelers, and we all slept on the floor in some student dorm that was the size of two match boxes. There were so many of us that we had to sleep on our sides, stacked up like vinyl records. And we all had the same dream. And then in the morning when we got up we saw these cereal boxes, and they looked like the same cereal boxes of sugar-encrusted, honey-glazed, saccharine-injected childhood sweets that we had known and loved only the boxes were ten times bigger than we had ever seen. They were like tall boy cereals, cereal boxes on steroids, and we looked at each in awe and marveling because this was America, where you could have more of the thing you didn’t know you wanted than anywhere else in the world. And if you got tired of that, no worries, there was someone in New York already thinking up the great new thing that would be coming just a few heartbeats before you really had to have it.

At the festival we lived on beer and sugar pops and watched programs that mashed up documentaries about gap toothed women and animations no child should ever see and movies that showed water dripping into bowls. We loved the movies that showed water dripping into bowls the best. We would argue about, you know, the way the drips in minute eighteen would be slower and hence more refined and hence more perfect, than the accelerating drips in minute 47. There was something in the rapid drip drip drip that was almost too, dare I say, commercial, nearly selling out, nearly pandering to an audience craving, even demanding, a pulse quickening, drip quickening, stream of a river of a lake of an ocean of water. We were not fans of the ocean. We were the children of oceans you have to understand, so we craved less. They had promised us everything, they had planted a foot on the moon, they had planted a gun in the mouth of every democratically elected leader in the southern hemisphere, so now we lived for less.

Silence

We wanted movies that would show us only one image, or no images. We longed most of all, for silence, and we found it here. There is no louder silence than the silence of a 1700 seat theatre, packed to the brimful as some eccentric, nearly blind kind of seeing flickers onscreen and there is nothing, no not even a hiss, arriving from the speakers. This was a silence that was reverential, astonished, why not come right out and say it: it was erotic. This was a silence that was erotic beyond our imaginations. We hadn’t known that this pleasure was also possible, and that this pleasure might arrive not simply from the wonders on the screen, but from the audience itself, activated somehow, as if by some unspoken chord everywhere felt but nowhere announced, to become agents of some new and temporary order, all of us part of some silent chorus, granting this undeclared gift to each other and adding our gravity to the rows fore and aft. A rippling, muscular, temporary and tender silence that even the ancient walls of this theatre struggled to contain. Even though it had been born in silence, this theatre, in the days when all of cinema was a speechless thing… you remember, don’t you, that cinema arrived small and silent? Like a child, like a speechless child, and only grew longer over the years, and that this festival, this Ann Arbor of a film festival would carry this old feeling, this history, these roots, would hold and carry these roots forward into a week in spring that seemed to last all year. And that it would carry it in silence, as a reminder of all the voices that could not be heard, of all the people who would never grow up to be president, because they were too black and too poor and too underserved by their schools even to have a 50-50 shot at not winding up in jail like the rest of their neighbourhoods.

This silence was before and after. This silence was the beginnings of cinema and it was a testimony to the silence that is still speaking today. In fact in today’s program, in the heart of today’s program, we are going to revisit this silence, which means to conjure it, to live inside it, to sing this silence again. To renew the vow. To listen to the choir of unheard voices. To open not as the eyes draw forward again and again to a point, to the point of it all, to the hierarchy of the beloved, to the one and only. Because the ears are a democracy. The ears are the root place of democracy because the ears admit sound from every direction, from every place. Unlike the eyes they do not create a centre and a hierarchy. They do not, in other words, reconvene some royal court, some old European royal court, with the king in the centre of the picture, and the hand servants, the peasants, the working class, off to the side of the frame, off at the edges of the field. Beneath notice. The ears are always opening, there are no ear lids, there is no off switch. Instead there is flow and circulation, there is an admitting. Not a projection (of power, of attitudes, of interests), there is instead a taking in, an acceptance, a receiving. And in this act of receiving, which is not the receiving of a royal court, but a receiving which creates an open field where the very low and the very high can be heard in the same tones, using the same language, the same sounds, in this act of receiving, when I can feel you arrive in my body, when I feel the sound of you arrive in this body, when I tune my body to your body, when I drop the assertions and preferences that the eyes invariably bring, when I open to you in the act of listening, then I cannot harm you, because you’re part of me. In the act of listening we become parts of each other, in other words, we realize interdependence. This is the heart of democracy, this is the physiology of democracy, at the root level, at the level of this body in this room. This is the lesson of democracy that is being held in this room, in this theatre, year after year. It is a demonstration, a modeling, a hope, but also a realization. Listening is not something that happens to you, it’s something that you do. Democracy is not something that happens to you, it’s not something that happens to a country, it’s something that you do. Or something you don’t do. Or something else is being done, that’s calling itself democracy, but when you tune in, when you listen, you know it’s not.

We wanted less. We wanted less over here, on the screen, so that there could be a little more over there, where it really mattered, in the seats, in the 1700 seats that belonged to the people. In the place of seeing that we would turn into a place of listening.

I believe that democracy begins in silence, not by an assertion. This is what I want. This is what I think. This is what I believe. I think democracy begins in a space of listening. I believe that democracy happens, is happening now, when we make space for each other, for the voices of each other, and most particularly, and most importantly, for our unheard voices. It’s not simply holding space for the usual voices, the headliners, the elected and unelected officials, the rich and the powerful in other words, who are always speaking, the usual suspects as the saying goes. But to hold a space for the unusual suspects, the one you would never suspect, the invisible ones. To hold a space for the unheard choir of your own voices. Not our shiny, perfect, know-it-all, top of our game voices, holding forth, one perfect joke landing after another, but the halting, despised voices, the voices of our weakness, of our miseries, the voices we’ve cast away and set aside, the voices inside us we find unbearable. How to find a way to hold these voices, the voices of our shadows? Because if we can hold these voices, then we can also hold the voices of those around us, the ones raised in accusation and pain and difficulty. The voices that aren’t trying to get along.

It is still my hope that difficult movies and difficult musics prepare us for this place, lay the ground for this place, for the unheard choir of our own lives. You showed that to me here, here in this room, here in this theatre, again and again. You showed me how to make a space for the unheard voices in programs that were too long, and too loud, and too silent, and too full and too empty.

Sangha

There’s another lesson I learned in this room, and this is the lesson of, the lesson of the third person, the lesson of us.

In the Buddhist world they call this the sangha, the group, the gathering, the audience, the audience that speaks, the audience that works. This is the sangha. And there is a kind of promise, or so the saying goes, that the next Buddha will not be a person. The next Buddha will be the sangha. This is what Thich Naht Hahn says, do you know who that is? He’s a Vietnamese monk, very important monk, very important person. It was the monks in his Vietnamese sangha, in his group, who set themselves on fire, in protest against their government, in protest against your government. Thich Naht Hahn lives now in France, in a monastery called Plum Village that anyone can go and visit. Thich lost everyone in the war. His whole village was destroyed. His mother and his father, his brothers and his sisters – they’re all dead. All killed in a war. Do you know what they called the war in Vietnam? They never called it the Vietnam War. Not the North Vietnamese, not the South Vietnamese. Perhaps they weren’t so different after all. They called it The American War. Can you hear the difference in that naming, can you hear the difference that naming makes. The American War. I don’t think you ever get over it, losing your whole family, but I think you can hold a space for them, for the unheard voices, the ones that can’t speak any longer. The ones who couldn’t be hear tonight. And perhaps in holding space for those voices, you might come to feel that it’s no longer important to look to our leaders, because the new leaders are going to betray us, just like the old leaders did. They’re going to call it the Iraq War. The Afghanistan war. They’re never going to call it what it is. The American War. The Canadian War. The Canadian War that never seems to end. Thich Nhat Hanh says the next Buddha is sangha, the group, the gathering. The next Buddha is us.

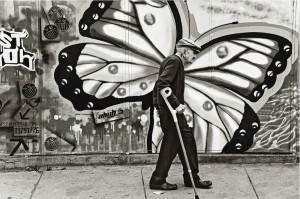

What does it mean to speak in the third person, to speak about us? What I used to think it meant was that everyone looks in the same direction, that we all nod in time, that we’re all on the same frequency Kenneth. But this is the great leader understanding of the third person. This is the eyeballed understanding of the third person. Of us. Because as the scientists will tell you, what ensures a healthy forest is not that every tree is the same, what allows an ecosystem to thrive is diversity, is difference. What makes our group strong is not that we are all alike, but that we are all unique and singular. In fact, I think it is our job, it our duty, to be unique, to celebrate our singularity, in just the same way these singular and unusual movies celebrate their eccentric seeings. Each of the movies we’re going to watch tonight, that we’re going to listen to tonight, observes a certain kind of scene. And sometimes that scene is very small, very circumscribed. It looks so private. I wonder if you can feel in this private place, a place that is dedicated to the way one person is absolutely distinct from anyone else around them, the necessary beginnings of the third person, the beginnings of us. It’s when you are being most fully yourself, that you bring to the room the necessary conditions for the third person.

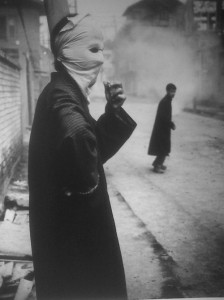

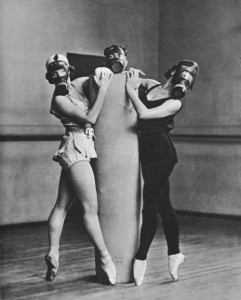

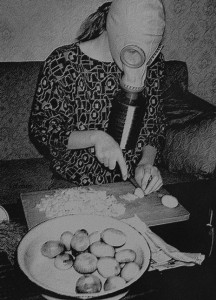

Mask

To be yourself. To thine own self be true. But which one, exactly? Which self am I truing, as the carpenters would put it, or perhaps we might ask instead: how can I express the chorus of my unspoken selves? Perhaps we could do this by putting on a mask. Give a man, Oscar Wilde said, and he’ll tell you the truth. He might have been speaking about the first film we’re going to see tonight. It’s called Asparagus by Suzan Pitt. It is a kind of creation myth, and the mask is a central feature. Perhaps every movie we watch, even the most banal or abstract, is a kind of mask that we try on. Is that me? Could that be me? Could I go that far? Could I feel that much? Could I allow myself to be touched that much? Doesn’t this question of opening, of empathy, lie at the very heart of the project of cinema? Suzan Pitt offers us her own version of the mask, perhaps as postmodernists like Derrida or Luce Irigiray or Jacques Lacan would say, there is no self, there is no fixed and essential self, instead there are a series of masks that arise out of a series of conditions.

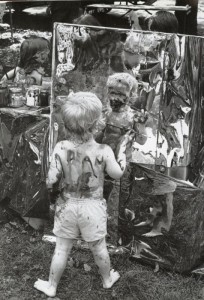

Suzan Pitt grew up in the heartland of this country, in Kansas City, and sometimes she says that her pictures, some of her pictures at least, some of her masks, also come from that place. As a young girl she chances upon an old house in the neighbourhood, given over to ruin and neglect, an unwanted house then, an unlivable house, and she climbs the stairs of that left behind place and finds in the attic a strange doll house. There is an abandoned house inside that abandoned house. Perhaps the dollhouse is the mask of all that has been left behind in that house. In her secret hours Pitt would steal away and up the stairs to go and play there, in this miniature, imaginary, realer-than-real world. In the private theatre of this doll house she could become, as so many children become, their own mothers and fathers, their sisters and brothers. They try on the masks, they take on a role.

There is a deliberate confusion in this film about what belongs inside and what belongs outside. The mask, it seems, is a fluid place, it allows a flow between what is usually kept inside, and what is usually kept outside. A mask is not just something you wear on your face, a mask can be a series of gestures that unlock the unconscious, the way a series of numbers unlocks the combination of a lock. When you put on a mask it can allow you to travel into the difficult places in your life, the dark streets of your own life, the unwanted chapters of your own life, because when you can open to the darkness of your own life, you can open to the darkness of others. This darkness, these bad neighbourhoods, are also a kind of wilderness. The artist lives in Los Angeles where she teaches at CalArts, and also in Mexico, and also in this state, in Michigan, where she has a remote cabin, a house that is not a home, that keeps her in touch, perhaps, with that wilderness. She often runs the exhibition circuit dishing a lecture about alternative histories of animation, call them the roads not taken, or taken only once, the hapax legomena of the animation world, and she relates this to the exploitation of wilderness, isn’t that interesting? She calls her lecture “Cartoon Wilderness.”

Fenz

How to say what you don’t know how to say? How to face what can’t be faced? How to live the revolution? The second film in this program is by Robert Fenz, a well known shooter for Chantal Akerman and Robert Gardner, amongst others. He worked for six years, between 1997 and 2003, on a cycle of movies called Meditations on Revolution. These films see him travel around the world in search of a face that is opening, as if for the first time. He is well known, best known, for his traveling, for his lyric accompaniments, as if he can sing along with the song of every place he visits. He is included in this program in part because he was born here, in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1969. In fact, there was a screening of the movie we’re going to see tonight in Berlin recently, and because the artist is poor he doesn’t have, you know, a thousand silver prints of this excellent and important movie, in fact, he has only two copies, and one of them is in the house of his aunt. So David drove over to his aunt’s house and picked it up so that we could watch it tonight. All of our seeing starts at home, or in the moment when what we always thought of as home turns into something else. A house within a house. Our seeing, the way we see, the way we put on the masks that we look out of, the masks that make seeing possible, perhaps it begins in the dollhouse we call home. If there is a power in the way that Robert Fenz looks it’s because his looking has roots, it has a foundation, it has roots, and the roots of his seeing are here, here in Ann Arbor. In each moment of his looking he brings Ann Arbor to that place, he brings the memory of this sky, of this tree, on this corner, in this light. He doesn’t arrive as a native, as someone who fits in, instead he carries his instrument like a jazz musician, he carries his horn, his axe, his prosthetic eye making machine mask, and he plays his instrument as a kind of accompaniment to what is happening around him. It is always a duet, it is always a duet between this place, the place you know so well, this Ann Arbor universe, and he brings the light of this place to that other place.

In Meditations on Revolution Part One Fenz arrives in a Cuba that is forbidden to Americans, subject to invasion and blockade, its leaders the target of dozens of assassination attempts. And what he shows there is a high contrast world of deep shadows and occasional public gestures lifted up out of those shadows for a moment. But in nearly every frame he points out what he cannot do. This is the most important thing in this movie, and what makes this a radical film. He arrives in Cuba not to show us what life is like, not to hold up a transparent window on the otherness of this revolution, but to point out what he cannot see. Look at this face, I can’t see it. Look at the side of this street, the side of this building, the side of this emotion. I’m here and I’m not here. I’m light and I’m shadow. In other words, Fenz refuses to pretend, he refuses the anthropological project that reproduces the other as part of a familiar vocabulary. Each time he sets up his camera the mystery deepens, this fathomless culture appears even further away. How few experts have the courage to say simply: I don’t know yet. I don’t understand.

The movie is twelve minutes long and it’s silent, in other words, you are the soundtrack, we are the soundtrack. And if silence, as we spoke about earlier, if silence is the beginning, the primal scene of democracy, perhaps we could see if we can feel, in the silence of this old new theatre, whether we might discover it again, whether we could live inside it again, here, for just a moment.

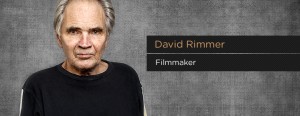

Garbage

There are three movies in the program. Asparagus by Suzan Pitt, Meditations on Revolution Part One by Robert Fenz, and finally Al Neil: A Portrait by David Rimmer. David was born and raised in Vancouver, and his movies recount the story, the history of that place. Walter Benjamin said that there are two kinds of storytellers. There is the one that is always on the move, bringing the story of one place to another. And then there is the storyteller who lives their whole life in the same village, who knows the rites and rituals, the secrets, the doubts and shame, of that village, and is able to spin their stories, the masks of their stories, from that place. Robert Fenz is the traveler, David Rimmer is the stay at home guy, the one who parks his camera in a window for several months, so that he can shoot a few frames every day, gathering up a record of moods and inclinations that look like the climate of the inside and the climate of the outside.

David was the garbage collector of the avant garde. He would take people’s garbage and turn it into something miraculous. Do you remember the instruction the Buddha gave to his sangha, his group, his audience, about the clothes they should wear? It’s India, it’s hot, and if you were part of the growing clutch that gathered round the Buddha you owned a single piece of clothing, a simple robe. And the Buddha asked that these robes should be sewn out of material scraps that had been used to clean floors, or as menstrual pads, or diapers. The disgusting unwanted parts of our lives, can we say yes to that? Can we wear them where other people will see them? David said yes, he was a magician with materials, he would take a small scrap of film and loop it and make it dance. He could find a whole universe in the corner of a room. And he had this friend, this eccentric, quintessential loner friend. For much of society this man was garbage, his music, his art was incomprehensible noise. But this man taught David how to listen, and this listening, this act of opening, particularly to the unheard voices, the difficult voices, the disgusting voices – this is the beginning of democracy.

David replays jazz as a family story. His fellow travelers ask Al to “play the changes man” but he can’t hit the breaks, off in a moment after moment that didn’t adhere to those timings. Perhaps he was trying not to decide, to keep this moment free of habitual preferences, even by the long lines of jazz maestros that had preceded him. And then later in the movie, Al rasps out the memory of his mother’s funeral, filled to the brim with strangers, with family he hadn’t seen in years, and he walks away from them too. This history of refusal becomes a strange and solitary music, as he moves away from the habit patterns of his own muscles, the happy making tricks and easy licks that too quickly become home, even for the avid improviser. The stuttering stops, the abrupt shifts in tempo, the reaching into the piano to find a more direct relation to the strings, all this is a way for him to find himself again at the piano as if for the first time, even as he continues to carry the refusal of the familiar in each note.

The woman with a mask, the traveler who never leaves home, the garbage man. I hope you might find some pleasure in these offerings, as I have found so much pleasure in the gifts that you have given me, by holding this space, the space of this theatre. The hope of the Ann Arbor Film Festival, I think, is not for a better world some day later on, but for a politics of compassion that we are busy creating together whenever we leave our lonely computers – connected to everyone and no one – when we come here and find ourselves again doing the work of the present moment as a tribe, a temporary collective, learning to speak again, to listen again, to live again in that most difficult and necessary place. The place of the third person, the place of us.