As soon as this 26-minute short movie (made in 2018) starts I can’t help thinking: why aren’t more films like this? Strange, weird, singular. I’ve never seen anything like it. It’s a media architecture created by the people who are in it, a collective of more than 50 Indigenous people living in Australia. It’s a story told and lived and filmed from the inside. Why does that feel so rare? I can’t help returning to this John Cage thought: Only what one person understands, helps all of us. If he was Karrabing he might have wrote: only what one tribe understands, helps all of us.

Adolescent capitalism, stampeding and gluttonous, transfigures what it touches. The forest exists for the axe to chop down and the desert for the train to cross; the river is worth bothering about if it contains gold, and the mountain if it shelters coal or iron. No one walks. All run, in a hurry, it’s urgent after the nomad shadow of wealth and power. Space exists for time to defeat, and time for progress to sacrifice on its altars. Eduardo Galeano

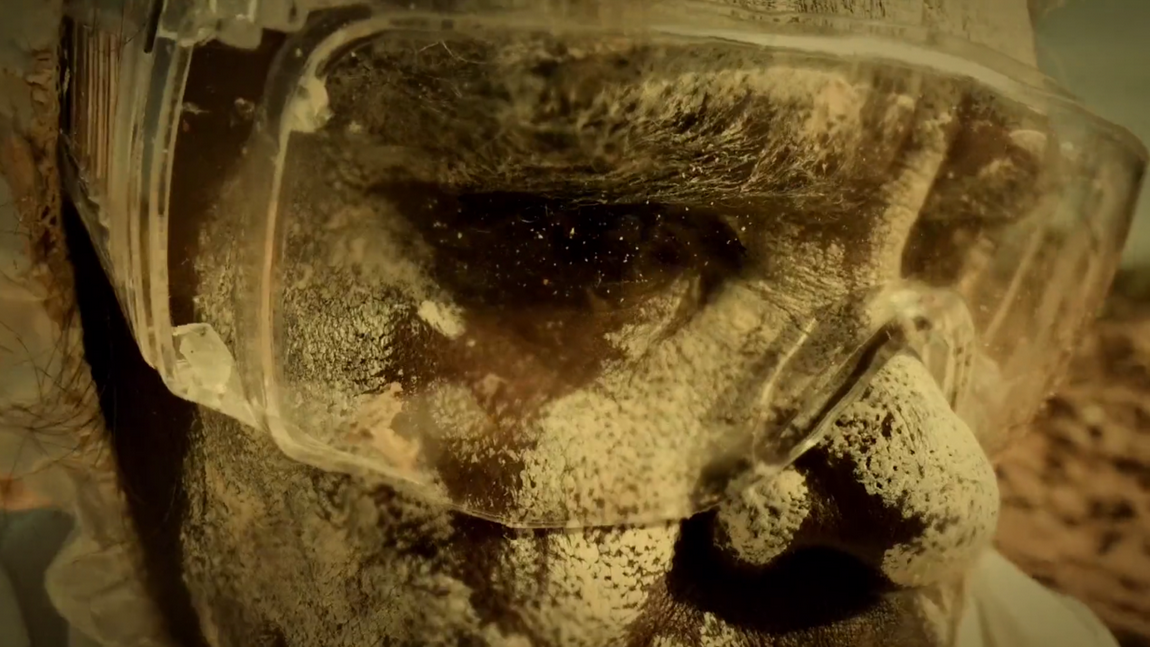

We are delivered to the end of the world, with eternal fracking fires burning, hospitals filled with the dying. While it is never explicitly stated, indeed much in this experimentalist fable is inferred, or else tossed off in mysterious asides, the sickness is capitalism. The fable tells the story of Aiden, who was stolen from home at an early age, so he knows little of his culture, and can barely recall his family. This film is a journey of reclamation, a way to step back into some of the traditions and practices that have been taken away.

For most of the 20th century in Australia, a “stolen generation” was taken from their families as young children and transported to faraway missions where they were trained as domestic servants.

Aiden is one of the stolen generation, now he has come back, in order to wander the land, and find the future in his past. When he is forcibly expelled from “the institution,” he wanders a country in ruins. He finds state workers in hazmat suits hunting down Indigenous youth in order to return them to “the mud,” a bubbling inferno of tubes and pain. Back in the labs, white doctors probe the secrets of Indigenous bodies, trying to understand how they can live in the toxic climate. But contact with whites infect Indigenous folks, the economic war is also a racial war, turning the tribe into birds and animals who are swept back into the mud.

Hovering over this elemental film of bees and fire and a Disney-coloured stream is the promise of the mermaids. These women hold the ancient wisdom of the elders, the ones who maintain the connection to the old ways. Whites had enslaved them too, but they have their own magics to call upon, and free themselves. They are schooling children in the lore, in the book of the soil, the volumes of tree and plant and sky.

Aiden walks through the bio-hazard quarantines, through possible futures and past, trying to reunite with his mermaid elders. Every tree has a parrot face and a story, father and brother appear to help him, the wind whispers secrets through the shredded leaves. The camera is close-up, hovering, always in motion, often centimetres from the earth, connecting bodies with their climate, their roots, insisting on the relationship between a person and everything around them. Each frame offers a democracy of seeing, as if everything was alive. Is it the most necessary, the most contemporary, the most urgently required movie made in the last year?

Karrabing Film Collective (established 2013, Australia) is a grassroots Indigenous media group consisting of over twenty members. They approach filmmaking as a mode of self-organization and a means of investigating contemporary social conditions of inequality. Screenings and publications allow the Karrabing to develop local artistic languages and allow audiences to understand new forms of collective Indigenous agency. Their films represent their lives, create bonds with their land and intervene in global images of Indigeneity.