May 28, 2020

Notes on a Crowdcast internet talk

sponsored by École d’innovation sociale Élisabeth-Bruyère Social Innovation School

Rethink

Capitalism exploits human life in the service of wealth. How can we reassert our well-being as a central priority? We need to work towards the end of a society of production, to create social structures that allow individuals and collectivities to prosper and not be continually enslaved in the service of a few.

We are living in a society where every aspect of reproduction that is central to our lives has been marginalized, and needs to be returned to its proper place at the centre of the wheel. Domestic work, raising children, the care for those who are not self-sufficient.

We also have to rethink agriculture. We need to move away from agriculture as the production of scarcity and death. Commercial agriculture benefits only people with money, it’s polluting the environment with chemicals that are going into the soil, the water, the land, and into our bodies. When we buy food we don’t know if we’re nourishing or poisoning ourselves.

We need a cultural transformation that puts an end to the distrust of others that is constantly instilled in us by the media. We want a society that values our relations with other people, because other people are the source of our creativity and our real wealth.

We have to put an end to the barbaric treatment of animals. All across the US Midwest they’re going to kill hundreds of thousands of animals because they don’t have the workers to process and sell them. This is a moment when we can see the barbarity of a food industry that is built on suffering. We have so-called farms with tens of thousands of pigs and chickens living together being fed all kinds of chemicals to keep them alive because the environment is so toxic.

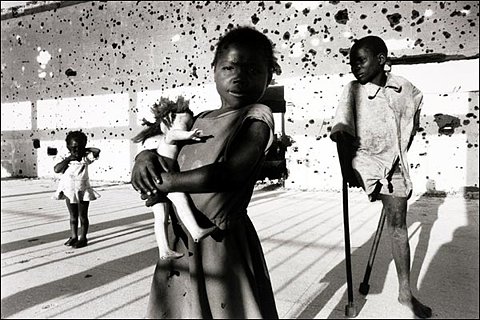

The ecological crisis, the treatment of animals, the destruction of land and water, comes with the expulsion of tens of thousands of small farmers across the world. This was not accidental. People do not leave their ancestral homelands by choice. They were forced from their homes because their lands are being privatized.

Commons

The changes we need to make are broad and structural. Today we have to engage constantly on two levels. One is the immediate level, that has to do with mutual aid, ensuring that our family is safe, particularly those who are marginalized and excluded. But at same time we have to think about the long term. The post-capitalist, post growth society has to rebuild processes of reproduction from domestic life to ecology to a new relation with animals. This will require collective effort.

My work in the past years has turned around the question of the commons, which is a social-economic-cultural principle. It refers to a society where collectively we have access to the means of reproduction, we make decisions about our reproduction, about the most important issues of our lives. We’re not passive recipients of judgments from above. We don’t have governments telling us because they know better. We have five hundred years of capitalist evidence that shows us how governments work to ensure the enrichment of the elite.

We need to shift our resources, and the production of wealth, and place it at the service of our reproduction. We need a reproduction that is much more cooperative, instead of each of us huddled away, separated in our homes. I want to say something about the question of growth that’s connected with consumerism. Consumerism is a symptom of a society where social relations are limited and unsatisfactory. We are so continually defeated by the lives we carry on that we need to replace them with objects. If our relations were more satisfactory we would not want to buy five pairs of jeans to fill the emptiness or massage the anxiety. Commodities are a way to feel more power in a world where we have so little.

Engaging in the struggle will allow us to find out: what is possible and what is desirable. Obviously there is not one model. As the Zapatistas say: “One no, many yeses.” We should be clear about what we don’t want: our new post-capitalism cannot destroy the planet. At the same time we should understand that a good society can be actualized in many different ways. This kind of reconstruction is the most creative work, and it’s necessary if we don’t want to doom the children we’re raising to a terrible future. This Covid pandemic is an alarm bell. We have to hear it, we have to make sure that those who control the outcome of this pandemic are not the same ones who are destroying the earth step-by-step. We have to put community at the centre, it has to be us. Then the new day can begin.

Pandemic

At this moment of the crisis there is a new global priority around social reproduction. Economies have been put on hold, and we have located the flashpoints of the crisis in nursing homes, refugee camps and prisons. This is the result, not of the pandemic, but because of neoliberal policies and globalization. These have sponsored both an accumulation of wealth and a concerted effort to destroy solidarity. In the covid crisis we see the crisis of food insecurity, the disproportionate impact on Indigenous and racialized peoples. And the need for agricultural initiatives that are citizen-friendly, we have to reappropriate agriculture.

This pandemic is the actualization of a crisis that has already been announced. One of worst areas of society has been the nursing homes. For many years I’ve worked in the field of elder care, I’ve read the reports and migod, people were already dying. The crisis in this area was there already. In a capitalist society everyone’s life is devalued, but certain people more than others. Elderly people, the working class, Indigenous people. People who are not productive any longer. Under neoliberalism resources have been cut for everyone, but the elderly have been the main victim of these cuts. It’s no accident that nursing homes are a disaster area.

Many are systematically malnourished. Medical supplies are low, medical personnel have been cut. All of this was not accidental. Hospitals were not prepared for the pandemic because there was a decision to have “just-in-time” health care, so you don’t stock up. It’s not profitable. This is important to understand. The lack of preparation and the many deaths are not simply the result of the unprecedented scale of the Covid crisis, but the result of government decisions to defund the health sector. The decision was made that life is not important, especially the lives of certain people. If we understand that, then we can ask the question: what needs to be done?

I see the importance of reclaiming a voice in our reproduction: food, schooling, health care. We need to have a say in what happens in the hospital. We need to decide: what is health care? This is not utopia. What does it mean to be healthy? What is health?

Food

If you look at the last thirty years on a global scale, you see one epidemic after another. Imposed economic policies of structural adjustment have resulted in a massive privatization of land and assets in the former colonial world, which has reduced millions to poverty, while illnesses like meningitis, cholera and ebola circulate. The pandemic has been circulating around the world for many years already. Unless we internalize this understanding, we will not be ready to create a movement and create the changes in everyday life and in our systems that we need to make.

What should we do? The system was built across centuries, that won’t change overnight. But it’s very important in the activism of the present, the response to the immediate needs of the present, that activism includes the long term reappropriation of social wealth: to reclaim land, to regain control over food production. We need to connect whatever struggle we’re making – whether it’s about student debt or health care – to our struggles over agriculture. We need to rally against transgenic food, against corporations stealing our water and destroying ecosystems. Every struggle has to include ecological demands, because this is fundamental to our reproduction.

We need to change how we live in this world. I’ve been very impressed by what I’ve seen and learned from women across Latin America, living in peripheral areas of Latin American cities. Here you find people who have been dispossessed from their land, neoliberalism has brought a steady recolonization across Latin America and Africa. Many are from Indigeneous or rural communities, and now they find themselves with nothing. What did they do? They might have despaired and drunk themselves into a stupor. Instead, they came together and collectively began to see how they could continue. How they could ensure they would not be defeated? They began to occupy urban spaces, start up urban gardens and form collective kitchens. And as they did a whole new social fabric was constructed, with new social relations, affective ties, new forms of solidarity. This is not yet the revolution, but it is a revolution. This new social fabric brings an ability to relate to the state in a different way, not as victims, but as a collective empowerment that can force the state to relinquish some of its controls.

Corporations know that if they control food production they control millions of people. That’s why it’s so important to take back control. That’s why the work of urban gardens is so important, it re-creates the commons, and it has multiplied, from Latin America to Africa, even here in New York. People are creating food production in their apartments, though of course many don’t have apartments. Food can be turned into a collective enterprise, a collective project, to break the isolation that capitalism demands.

We have to pose the question of the defeminization of reproduction. Capitalism has left women to do all the work of reproduction, the work of caring for the sick, of raising children. I’m concerned that sharing this work, defeminizing reproduction, becomes the only goal. Sharing homework with a man is better than not (though many women live alone) but that is only part of the solution. The division of labour also divides people according to gender, race and sexual preference. Those inequalities, those hierarchies, are the main obstacles. Racism, sexism and homophobia are the main obstacles for us coming together to realize the kind of commoning I’m talking about.

Post-capitalism

How do we organize the post-capitalist society? When Marx was asked: “What is communism?” he replied, “It’s not an image of another society. It’s the work that changes the status quo on a day-to-day basis.” We have to realize our vision step by step. Right now our imagination is very limited because we have interiorized the idea that there is no alternative, capitalism has become so naturalized. We need to revolutionize our existence on many levels. We need to be more modest and concrete. We can discover what’s possible by building it. We need to move away from the idea that there is one model, one way forward, but being clear about what is unacceptable. The desirable must be continually constructed.

The question is how to change our relation to work, and to use the wealth that we produce in a different way. We need to be able to make decisions about that wealth.

We need to connect different struggles. This is a process that isn’t at point zero, it’s already taking place. If you look at Chile, Ecuador or Argentina, there’s been a tremendous amount of networking by women. The Indigenous movements are connecting with feminist movements. The landless people of Brazil who are doing collective work in the fields are opening up shops in the cities where they’re selling produce. There is a circulation of the struggle that is already taking place. The connection of different struggles, that circulation, is where our energy should go.

Written from Below

We have to approach the question of the commons in a very critical way. It’s a term that’s so overused that it’s come under suspicion, it’s been derided, denigrated, sneered at. In the history of capitalism, every time there is an important concept it’s always immediately taken over. Think of “democracy” or “feminism.” The left is in a process of constant retreat. We come up with an idea and then it’s used against us. I like the word “commons,’ I don’t think it’s a question of finding a new word. Though the semantic is also a site of struggle.

How to stop “the commons” from being used against us? The World Bank insists that they are the keeper of the world’s oceans, a commons for all. But their policies have displaced millions, and they’ve helped elect high-placed capitalist officials who are busy turning former commons into real estate markets, replacing Indigenous villages with mining operations. The World Bank’s claim that they are protecting the world’s heritage is obviously false. Half of our forests have been burned down under the control of the Bank. Not to mention the mining code… but we don’t have time to get into that.

Today the production of knowledge is increasingly commercialized. In the US we speak of the university as an edu-factory. How can we work together to decommercialize knowledge? In Latin America there has been tremendous effort, included in the concept of the commons, to recuperate collective memory. To reconstruct lost knowledge. It’s history written from below, written by those who often do not write history. It represents the construction of a collective subject and collective interest that is fundamental to the struggle, it’s what gives the struggle meaning. The concept of the commons has many dimensions, but it requires a material basis. The loss of land is a loss of knowledge of plants and medicine and lore that has sustained the health of Indigenous peoples. This is what is meant by the commons.

7 Generations

Let’s establish some principals. For example, commoners should be the ones who make decisions about their own reproduction. Those who make decisions about land and food production are those who are producing their society. The commons is not a free-for-all. The earth is not open for all takers.

The wealth of the world is a wealth that has to be cared for and reproduced so we can live the way Indigenous peoples have envisaged, according to the principle of seven generations. In personal decisions, in self-government, in the commons, in our government, every decision needs to take into account its effects on our children seven generations into the future. This requires a constant engagement with our wealth, with how we use the land, the herbs, the fruit, for our sustenance. It requires cooperation. How can we ensure that the ecosystem thrives with our presence, instead of being destroyed by it?

Land commons are the foundation for every other kind of commons. I use the word “land” the way a campasino uses it, to indicate waters, animals, trees, the ecosystem. It’s a broad term. Wherever there has been widescale land theft, for instance with the landless people in Brazil, there are corresponding examples of land commons. These social movements and women have delivered me from the temptations of pessismism. Yes it’s too late but tomorrow is another day, and children are still waiting.