Lost

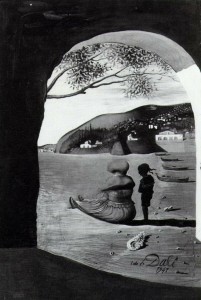

“When we write we offer the silence as much as the story. Words are the part of silence that can be spoken.” Jeanette Winterson

1. Arrivals

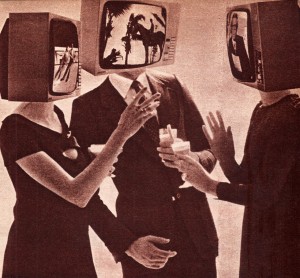

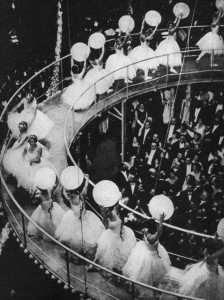

All the movies I watched as a child assured me that love occurred in an instant, perfectly replayable, rewindable, rewatchable. It usually happened with a shared look which arrived as a prelude to language. Love was the unspoken prelude, the sudden thrill of recognition. You. It will always be you. Perhaps as a nod to the new physics, it arrives at the speed of light. “Just one look,” as the song goes, “that’s all it took.” Curiously, this instantaneous and double-sided explosion marks a passage that can never be withdrawn. It happens before you know it happens, as if one is part of a force of nature, caught up in a personalized hurricane shared by exactly one other, and once you’ve both felt it, there’s no turning back. It takes no time at all, and then it lasts forever. At least these are the models, the motion picture molds that I was born only to repeat, to pour myself into.

Let me begin with a confession: I didn’t fall in love in Vila do Conde, I was already one of the fallen. But she hadn’t yet. Is it too shameful to admit that we had met at yet another festival, and one that had decided, in a fit of adventurousness, to dedicate a swath of prime time festival real estate to movies I adored? She watched everything with a kind of democracy of attention. She never missed a program, absorbed everything and nothing, and held forth with an alarming critical alacrity about everything except the movies which consumed every other waking moment. I followed her around like a small circus animal, the more she ignored me, the more interested I became. Call it the geometry of desire, the necessary precondition. Instead of the gaze of recognition, the promise of invisibility. It proved irresistible.

Talk

And it made me wonder. Was every festival only a backdrop to encounters like this one? One-sided, like the cinema itself, where one party does all the talking, and the other all the listening? Where projections can grow in the dark, where we can shine our unfinished and imperfect self projects on those who are sitting near us, caught in this most temporary of communities, this urban whirl of too many pictures and interstitial cocktails. It might have struck me then, not for the first time, how little conversation at a difficult movie fest concerns the movies. Yes, this was yet another annual gathering of difficult movies and the difficult people who make them. But between us we could only muster a few words by way of critique, an occasional opine could be heard floating over the cigarette haze. Even though the crowd was bursting with writers and thinkers who filled books in private, here in post-screening festival scrums voices were simply raised for or against, as if in a voting booth, or more likely, a mall, where an overwhelmed consumer is confronted by purchase options. I’ll buy that. I won’t buy that. I don’t know why, but at the media arts festival the mind reverts to its suburban doppelganger, we all become shoppers again. Or Olympic judges. That movie is an eight. That movie is a six. And then it’s right on to the important matter at hand. Who is falling in love with who? Or if not falling, then at least stumbling, keeling over, leaning in that direction? Yes, it seems the movies, even these avant garde snackables, are merely the backdrop to personal tabloid gossipings.

Arrival

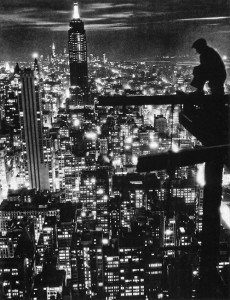

It’s a bad habit, this replaying of scenes from old movies, they’ve trained me too well. But the experience of arriving in a new city is so often carried out via airplane, and who can forget that delirious opening shot from Triumph of the Will when the clouds part to reveal the fuhrer, descending from on high to his fatherland. As a result, I can’t help regarding every flight staff with suspicion. Why have they chosen to repeat this messiah experience, again and again? But never mind, it’s cloudy across southern Europe today, and after a whirlwind of circling the ground seems to rise up and catch the plane in a violent lurch that pitches my neighbour against the overhead racks. There is the smell of vomit, and the ashen faces of apology from the staff. The passengers, unnerved and shaken, applaud.

A young boy is there to meet us, he holds the sign of the great Vila do Conde festival in one hand, and what looks like a manga comic book in the other. I’m too young to wait, this is what his posture says. He hustles us into the car, and then we set off for the festival itself at terrifying speeds. I am grateful to be sitting in the back so that the looks of outraged drivers are mostly registered on my fellow passengers, whose faces eventually fall into a fearful paralysis. If death occurs, it will happen quickly, and the driver’s controlled recklessness (is he actually tall enough to see over the steering wheel?) ensures that our impact will be maximal, no need to worry about a shattered spine or exploded organs, they can take us straight to the funeral home when we’re done.

The fantastical speeds of the European roadways are another way of losing myself. I can feel myself jumping out of my body, I give myself over to this child who has obviously overpowered our usual driver and has dedicated himself to delivering foreigners to the afterlife at optimal velocity. In the cinema, this is called the establishing shot. And in the world of the festival, the establishing shot is delivered at maximum speed and maximum disorientation. The look on our young charge’s face says: everyone needs a mission, something to believe in.

Reborn

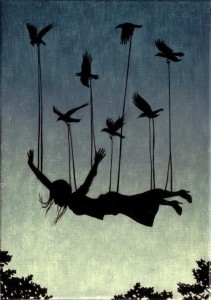

The festival experience means for most a solitary arrival. In the future no doubt this will become a fine printed stipulation. We may have brought our baggage, our personal electronics, our best foldable outerwear, but what has been left behind is muchly more important. Our domesticated life, the routines of monogamy and child care, the responsibilities, in other words, of adult life. We are here to celebrate, and in order to celebrate it is necessary to become someone else. This is a conversion that must be strained through the messiah flight, a shedding of contextual markers, the shadows of employment. Because the people we used to be could never feel this much joy, or this much dissatisfaction. At the festival I am ready to stretch out both ends of my experience, bring it on, good and bad, in equal heaping doses.

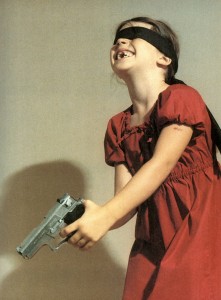

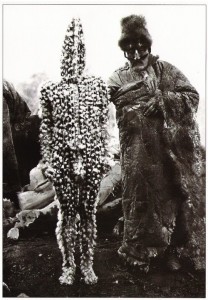

At every festival we may be reborn as children, jobless, parentless, shorn of every duty and obligation except for the rigours of watching, or at least, holding up a conversation or two in the bar. Are we having fun yet? The festival invites its artists and audiences to become something completely unexpected, to wear a new face, never before seen. It celebrates the masquerade, the camouflage of presentation, favouring the quick bon mots over the all night conversation, unless these are the overtures to further extimacies. Each movie presents us with new presentation models, I slip into each one as if it’s a second skin, and when the festival is dedicated to showing short works, this can be a dizzying enterprise – like a teenage girl throwing one glittering top after another on a growing pile. No, not this one, not this one, not this one… But before the discard, there is a promise, a moment of hope, yes, this could also be me. I can also look like this. One of our watching keynotes is simply bearing witness to a never before seen or imagined situation and nodding in time: yes, I could also be this. That small child with the bullet hole in his chest on the Gaza Strip, the mother who has lost her home, the rapper avenger lighting up the neighborhood. And when we recognize ourselves there, it’s not simply an extension of the old colonial grasp, they are not being remade in our image, we are being remade in theirs, as if we were also something over there. Our intimacy and our distance is proclaimed again and again in these short conjurings of other worlds, the other lives we might be busy leading, and which we enter, secretly, like revenants at the end of a mysterious pilgrimage, putting on the clothes, taking on the language and customs. My body expands until it covers the whole world. My skin is stretched tight as a balloon until it wraps itself around every face, every shrunken and swollen belly.

“Empathy is the nature of the intoxication to which the flâneur abandons himself in the crowd. He… enjoys the incomparable privilege of being himself and someone else as he sees fit. Like a roving soul in search of a body, he enters another person whenever he wishes.” (The Writer of Modern Life: Essays on Charles Baudelaire by Walter Benjamin, p. 55)

Secret

And of course we have come to the festival to share a secret. What possibility could there be of creating a group, a sangha, a tribe, without the reckoning of a secret? The dark mystery that lies at the very heart of the matter can at last be spoke. It is simply this: that when we arrive at the festival we are hoping to see something that we’ve never imagined possible before. It’s not simply that we want to see a good film. If we wanted to see a good film we would buy a ticket for one of the in-town offerings and cross the temporary stanchion of the one-night stand. But a festival is a different kind of not-knowing altogether. It is a plunge, nothing less. We throw ourselves into the bevy of offerings, needing to be lost and found, and holding beneath it all our secret hope: that we will see a movie that will change the code.

When we were 16 or 17 – for everyone the age is different of course – but there comes a moment in our lives when these code shifting experiences might happen daily, even hourly. You could fall in love fourteen times in an afternoon, every conversation was the final word, every movie was a paradigm shifting apocalypse. This is the secret promise of the festival, some forever young promise of renewal, that we could reach back to a moment when youth would no longer be wasted on the young, so that at last we could be old enough to appreciate being young, and being young again we might be reborn, recast through the thousand shimmering reflections of these movies until we emerged from the other side, staggered and shiny and a complete stranger. What’s my name again? I come here to lose my identity. To be remade in the factory of personality replacement therapy that the festival promises. And every face that sits beside my face, that stares back at me from the festival café, is also part of the movie, the necessary transformation, the delirium that we are busy embracing, as if this was the very last day on earth, because of course it is.

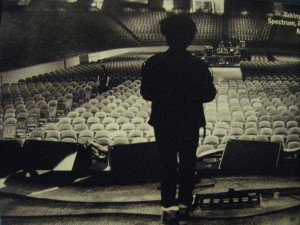

“Whoever is not busy being born, is busy dying,” Bob sang to us, in a song that reminds us that he has been dying for years already. The trick is not to have too much fame, or recognition, and on the other hand, not too much poverty and horror and difficulty. Call it the middle way. And the middle way is only a preparation for the excess of the festival, where we can at last wake up each morning as someone else, our dreams stuffed with pictures from around the world. At the festival the curators gather to cull the waking dreams of the cinema, and as we watch them during what Freud called “the dream day” we gather material for ourselves, we collect moments that can be reconfigured later, when we can at last relax into the sway of the unconscious, and allow ourselves to be played and pictured. And so we incorporate the fantastical vantages of the festival into our own pictures, replayed as if we were somehow central to their unfolding – or perhaps the festival will allow us to relinquish this role as well. How very tiresome to spend so many of our nights in a hopelessly narcissistic involvement, as if the world was arranged so that we could experience it. Perhaps in the full thrall of the festival’s avalanche of pictures it might be possible to let go of this treasured vantage, the what’s-in-it-for-me, infantile capitalist forever bawling out demands, each moment in the picture plane returning neatly to the vanishing point located somewhere between two staring eyes. Could this nighttime relinquishment be a welcome side effect of the festival, its effects no longer aimed at the measurement of visible activities, the newly clipped speech rhythms, the swift appraisals of attire and attitudes, the lightning fast visual cue receiving and sending stations that the face becomes? No, all this might prove to be secondary to the dream work, the hopes of the night granted precedence over the hopes of the day.

Adam Phillips

“…if you’ve had a mother, or parents, who have been extremely overstimulating in their demands of you, then this trauma of the available media is precisely your medium. It’s like returning to the scene of the crime. Consciously the thought is, ‘This is all very exciting,’ which it is, but unconsciously the thought is, ‘Will I be able to survive it?’ There is this massive demand on you and the question is whether you can do anything with it. I feel, very powerfully, that demand. This might be a slightly mad idea but there is a risk that we’ll have our sensibilities blurred, not simply by compassion fatigue, and so on, but by an overload of stimuli that doesn’t give anybody enough space to develop their own sensibility or discrimination. It’s as though there is a real terror around of people having their own thoughts about things, and so people are being assaulted with simulation. It’s like pornography preempting sexuality.” Adam Phillips by Sameer Padania, BOMB Magazine, No. 113, Fall 2010

Too Much

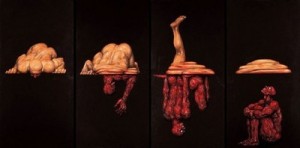

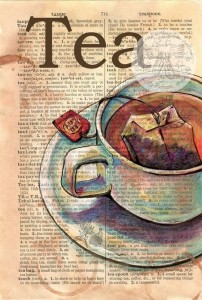

There is a famous story about an august English scholar who has recently undertaken a study of Zen practices. Serious in his pursuits, he travels to Japan to meet a real maestro, someone who has spent long hours on the cushion contemplating the open field of experience, unimpeded by the necessarily restraining demands of a self that is only a collection of fictions. The scholar is invited in to the temple to practice, or to observe practice, and then to a special room where tea is served. Every moment is practice, every gesture counts. The world is also the temple. The guest is offered a handsome cushion, tea is made, and two cups are set out. The zen maestro approaches with the teapot and begins to pour, but instead of stopping the flow when the cup is full, he keeps right on pouring, as tea cascades over the sides of the cup, spilling onto the floor, the handsome cushion, the handsome man sitting on the cushion.

What is this old story trying to tell us? Has the scholar already made up his mind, perhaps? Has he come to ask questions he already knows the answers to? Perhaps his cup is already full, and he has shown up as if there can be more words, more understanding, more practice, that can laid inside his cup. But recognizing his true intentions, the zen master offers his visitor a mirror, a mirror made of overflowing tea. Or perhaps his arm was tired, or Englishmen bored him. How can we know? But this much is for sure: it’s too much. There is too much tea. It’s a story about too muchness, and what is a festival, if not a story of too muchness? There are too many movies to be seen, in too many theatres, and too many new people to meet, and too many old people to avoid meeting, too many old wounds to cover, too many new hopes to squash, too many different pictures from too many places.

Pictures

Tell me, quickly, do you really think you need to look at another picture for the rest of your life? If we were peasants in rural China living a few hundred years ago, or in many other places in the world, we might only see two or three pictures in our entire lifetime. Were they poor, while we are rich? How many pictures do we need exactly? Or is need the wrong word? What word would you use, to describe your relation to pictures? How long do you go before seeing another? I mean a picture of any kind, still or moving, what duration is there between moments of picture viewing?

Perhaps, as Adam Phillip suggests, we are leaning back to replay a childhood moment, when our over demanding parents were calling out. Not content with the tidal wave of internet offerings, the facebooked links, the leavenings of friends, we decide to head to the festival, where we can drown ourselves in the cascade. Bring on the flood. Let there be too muchness. A horizon of too muchness. And perhaps, as Phillips goes on to say, we immerse ourselves exactly to find out how much can we bear. Whatever doesn’t kill us, turns us into a picture. How much can we stand? How much too muchness until we find our limit?

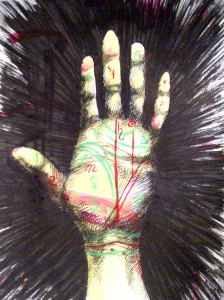

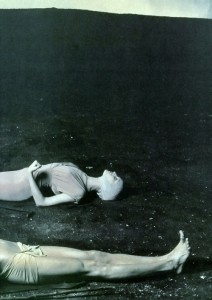

Wound

Perhaps we are drawing our perimeter, our shadowy outline, our self container, as these pictures wash over us, buffeting our cherished identities, the shorelines of our traditional selves quickly eroding and then restoring itself, and then giving way again. Yes, we arrive at the festival with our cup too full, and then we play both parts: professor and Zen master, tea pourer and tea receiver. We grasp the pot in both hands and pour from the infinite tea pot of our too pictured world, filling our already overflowing cup as a testing of limits, seeing if we will be able to emerge from the fray after all, or whether we will leave this place with the stain of it on our faces, where everyone can glimpse it. Oh, I can see by the mark on your face you’ve been to the Vila do Conde festival. How wonderful. How terrible. Anne Carson, the great Canadian poet, writes: “Every wound gives off its own light.” She might have written instead that every festival encounter will leave its indelible trace on all those who have given themselves fully over to these carnivals of transformation.

One Person

We continue to imagine that we are one person, perhaps it’s a mirror phase hangover. When we see ourselves in the mirror, we appear as one person, all at once. Lacan theorized that the infant child met up with this glassy summary in amazement, that the riot of sensations could be gathered up in a single place. But I think this experience is happening again and again, or at least, the physicists insist that our selves are atomized, approximate, unstable fields. Physically speaking. Scientifically speaking of course. And what we conjure in the face of their evidence, the dream that we apply to our fractured and fragmented existence has to do with continuity, we smooth over the ruptures and gaps with storytellings and fairy tales of the self. But something in us lives in solidarity with science, there is an inner physicist who wants to feel again the reality of our relative, conditioned-arising existence. And so we pack our bags and head for the festival, where we can unleash a torrent of pictures against our tried and truisms, directing the unrelenting stream against the apparent certainties of our self. How much can I bear? This is the old question, the old refrain, picked up again and again. How much too muchness can I bear?

Eat

Adam Phillips: “There is a strange, magical idea that you can consume without digesting, that you could eat without swallowing, as though there were no process. Again, a psychoanalytic analogy comes to mind: it’s the difference between a mother who needs to feed her child, and the mother who waits for the child to have an appetite and then feeds it. It’s an absurd cartoon, I agree, but capitalist culture is force-feeding us whether we’re hungry or not. What this means is that we never know when we’re hungry, and we don’t have the space to figure out what it is we want. It’s driving us all mad.” Adam Phillips by Sameer Padania, BOMB Magazine, No. 113, Fall 2010

Is it politically irresponsible to be creating pictures now, in this moment when there are already too many pictures? Are we simply giving in to the cultural habit pattern of our time, the capitalist force feeding machine that Phillips is describing? Perhaps there is already a tea pot flowing, a thousand tea pots flowing, and just a couple of cups to catch all that tea. So why add our own meager offerings to that vast collective picture making exhale? And more than this: why indulge in the hyper-capitalist mode of consuming pictures one after another, as if our computers weren’t already capable of delivering more than we could stand? Is the festival the mother that feeds us even when we’re not hungry? Do we have time and space enough to digest anything at all between the festival’s movie offerings, between these prime time extravaganzas of the imagination?

Fringe

But wait. Perhaps the flood is necessary after all, in order to relieve us of the burden of our certainties. Our stale dated convictions. When I was a young old man, I was convinced that experimental movies were the beginning of the revolution, first we would change the pictures, then we would change the world. And I was quite clear, in those long ago nights, about what exactly an experimental movie was. It was something that could be calibrated and identified, hatpinned and captioned. I tried to shore up my newfound convictions in the traditional manner: by huddling with others of my kind, and by rigorously excluding all those who had no allegiance to the newfound faith. Being socially awkward and shy helped immensely by limiting contact with potentially contaminating opinions. Years later I was doing an interview with Canadian video artist Wayne Yung who remarked that there were no more than three or four movies produced each year where the lead was gay and Asian. And I’ve often attended screenings in the many micro-community film fests here in Toronto, the one dedicated to Japanese short movies, or to First Nations experimentalisms, for instance, and realized that what was and wasn’t avant garde depended very much on who was seeing it. And this produced a delicious confusion. Screening more silent super 8 shorts about wind and trees for the usual suspects suddenly seemed a lot less daring than having one of Wayne’s movies play in front of a feature length anything, for instance.

And for reasons that remain mysterious to me, people are willing to accept experiences at a festival that would be unseemly outside its warming embrace. Everything from technical snafus, unsubtitled movies, long winded introductions, line-ups in the rain, all these are braved by intrepid publics who are purchasing for themselves a moment of suspension, a bit of relief from the old certainties. The familiar roster of judgments. The festival provides an alibi for its public to escape itself, as if we were stealing out of our own lives, and becoming part of a panoply of possible selves, tried on for laughs and cries, under the forgiving allowance of the festival. Who are you again?

Losing Time

What is so helpful about movie festivals is that they happen in real time, as the saying goes, and in a real city. Watching the same selection of shorts and longs streaming on the internet is no substitute, just as buying books on the internet is no substitute for a book store. Because on the internet you are efficiently delivered to the book you know you want. But in the bookstore you are inefficiently delivered to books you don’t know you want. In the bookstore (will there by any left, by the time this is published?), the possibility of an un-useful time opens up, a time that is not commandeered and driven to a point. Call it browsing. The art of losing time. Cinema is the art of losing time. And naturally enough the film festival was created in order to extend this art of losing time. It is such a gift, particularly now, in this timeless time, with its mounting pressures for incessant digital contact, to be able to wander through the theatres, the cafes, the unfamiliar faces that are turning into a new family, the familiar faces that suddenly appear strange and faraway. We need this time, now more than ever, so that we find ourselves, and our memories, by becoming lost, entirely disarranged and incomprehensible. The festival invites us to give up our cover stories, to leave our proper faces at the door, to surrender to our secret ambitions, to ambush our best intentions, to speak as if we didn’t already know what we were going to say. In other words: to invent. The festival invites each of its participants to invent themselves, to relinquish the convictions that are busy turning so many of us into parodies of ourselves. As if we were cast in the same play night after night, forced to emit the same cloud of language in the same way with the same results.

2. Letters

Mike,

Thanks again for your kindness to write me and hoping I’m smiling somewhere out there, but again I’m not, hardly able to laugh. Things are getting worse it seems, with my mother (too tired to tell but she’s at her end, has a new/final breakdown and there is no way out but suicide which is a last and difficult thing to do and to dare), at school (chaos over there, and a lack of appetite to start another new year) and most of all with this thing called love.

Yesterday, after not having seen each other for a long time since he was in Greece for weeks, to work there in a restaurant (and finding someone, I was already thinking of that) I received an email from Manfred in which he tells and asks me this and that as if nothing happened and then in the second last line he mentions, among all the things he did in Greece, that he found the love of his life. Boom, just like that. And that he was curious about how things were on my side. I was shocked, I couldn’t say a word, so I wrote him I couldn’t say a word to someone in whom I saw a possible love of my life now that he all of a sudden had found his…”

This is how we write each other, how we find each other, through the words which we prefer to touching, through the long distance feeling we prefer to feeling, and most of all through someone else’s love. We uncover our secret, our secret desire, by being able to speak about our dashed hopes, the promises raised and smashed, and then huddle beneath the shade of them with one another, as if in consolation. I know the way this is supposed to happen: on our first encounter we should exchange a look that contains within it all the looks we will ever have. We are supposed to share a look that is already a prophecy, a look that will never end. This borrowed fantasy (are they all borrowed?) is as clear as it is cruel. The single look, the one and only, signals that once again we have theology rewrapped in desire. I love you is another way of saying God. The two of us, on the other hand, are finding our way together without the help of higher powers. We are stumbling in the dark, perfectly lost. (Can you feel the grieving in each line of her mail? The cost of writing these words?) This love story is triangulated, it isn’t only a question of a him and a her, but of a project, a “love of my life” that is lost, and in the wound of that catastrophe, something else grows. This, I think, is also the heart of the fringe enterprise. Experimentalist movies emerge exactly from this place where something is missing. And it doesn’t attempt to cover up this place with smoothly delivered gender roles, it offers viewers instead the opportunity to feel what it’s like to be a tree for an hour, or a barking dog chained to a fence, or a woman’s shoe. It suspends our usual attentions, and carves out a bit of the world that we might dwell inside for a period in order to remap our attentions and our sympathies. The movie produces a third term, like the lover who is not a lover described in the mail. This is exactly the place of the movie, it is a lover that is not a lover. And like this missing and absent lover, it produces the conditions for another kind of love, is it too much to suggest, another kind of subjectivity, along with alternative modes of self production.

She arrives in Vila do Conde smelling freshly of disappointment and anticipation, a heady cocktail. If she’s uncertain about the man she’s meeting there, she likes the idea of a foreign city, the prospect of the beach, a film festival in which she can turn into someone else. I think we are both looking forward to turning into something else.

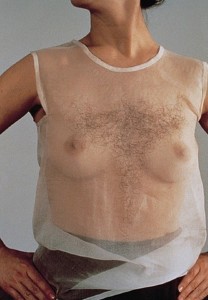

She paces the room as if there are an army of soldier ants beneath her perfect feet, though something in the clean lines of the Santana Hotel reassures her. The anonymous ideal of the modern hotel, the sense that we could be anyone here, we could step into the shoes of the former occupants, begin a new life, even a new love, all this might be possible in this sleekly appointed and perfectly generic bed, with its twin reading lights offering the possibility of a last spotlight, a final soliloquy, before surrendering to the gravity of sleep. Oh yes, the bed stretches out before us as an unkept promise, this anonymous bed that has harboured a thousand anonymous sleeps. Perhaps everyone who lies here has the same reassuring dream. It extends itself as promise and threat, is this the first of our beds, the first nakedly lost and prone and helpless lying together? Or the last? She turns the television on and off, pulls out the desk drawers, opens the Portuguese dictionary they have lain discretely inside the nightstand in place of a bible. She is so nervous that everything delights her. I am so nervous that her delight only makes me more nervous. I offer to rub her back, it seems easier than negotiating the tangled mechanics of kissing, and she happily submits, she’s been cramped into Euro shuttle planes for much of the foggy morning. She turns from detective into client, while I try on the hats of hostess, tour guide, artist, and bewildered teenager. We don’t know who we are, or what we might become together in this place, and the promise of all that unknowing is more happiness than either of us has been willing to admit for a long while.

The massage rolls out and then the first clumsy embrace, the collision of strangers, the faraway smell suddenly so close, as we slide across the universe of each other until at last we are part of the same constellation. The maid comes in once, twice, three times. Well, OK, she doesn’t come right in, she opens the door and closes it. Determined that the room’s modernist imperatives remain clean and dust free. Nightime comes and we are still turning. I didn’t think the body had so many corners, but everywhere there are new discoveries and recoveries and frissons of the unexpected. After weeks of talking our hands are finally allowed to speak to each other without the promissory notes, the prospect of later, the cautious optimism, the whole Santa Claus bag of past hurts we like to drag into the room with every word we speak. We have to touch away the words, we brush the language out of our pores so that we come down to the skin and the muscle and the bones and we find new words there and we stroke them until they are part of the pleasure too. Everything comes along for the ride. Everything says yes. And then we are there, all at once, and at the same time, her face as large as the night sky, it grows larger and larger until it falls away and I follow it back down to the ordinary bed where we are only mortals. And because I am terrified of this new person we’ve become I start talking in the old way. I say, in clear violation of the very first rule of the Santana Hotel, never mind the ten commandments of Portuguese romance, “Wasn’t that incredible, we had the same feeling at the same time!” And she looks back at me as if she were still back in Ireland, still at home in that old dusty limerick of a place, and replies, “What are you talking about?”

And then we are only our old words, we build up the castle walls with them as quickly as we can and we are lost. She showers and announces it’s time to go explore this new village, and that she’d like to do that by herself. This is how we spend the rest of the festival, ducking in and out of our newly found selves. I watch her flirt with the beautiful young filmmakers from Porto. And still we are hovering, at the threshold, not quite a couple, not quite apart either. Uncovering a new kind of loneliness that we savour as each movie rolls by, offering us the prospect of newer and more forbidden selves that we are almost too afraid to become.

“The capacity to be alone can only be developed with someone else in the room. Once it is developed the child trusts that she will not be intruded upon and permits herself a secret communication with private and personal phenomena. The best adult model that Winniccott could find for this is what he called “after intercourse,” when each person is content to be alone but is not withdrawn. This is a very unusual state because of how little anxiety exists. There are no questions about the other person’s availability, but there is also no need for active contact.” (Going to Pieces Without Falling Apart by Mark Epstein pp. 38-39)

3. Lost

“If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will take you there.”

Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

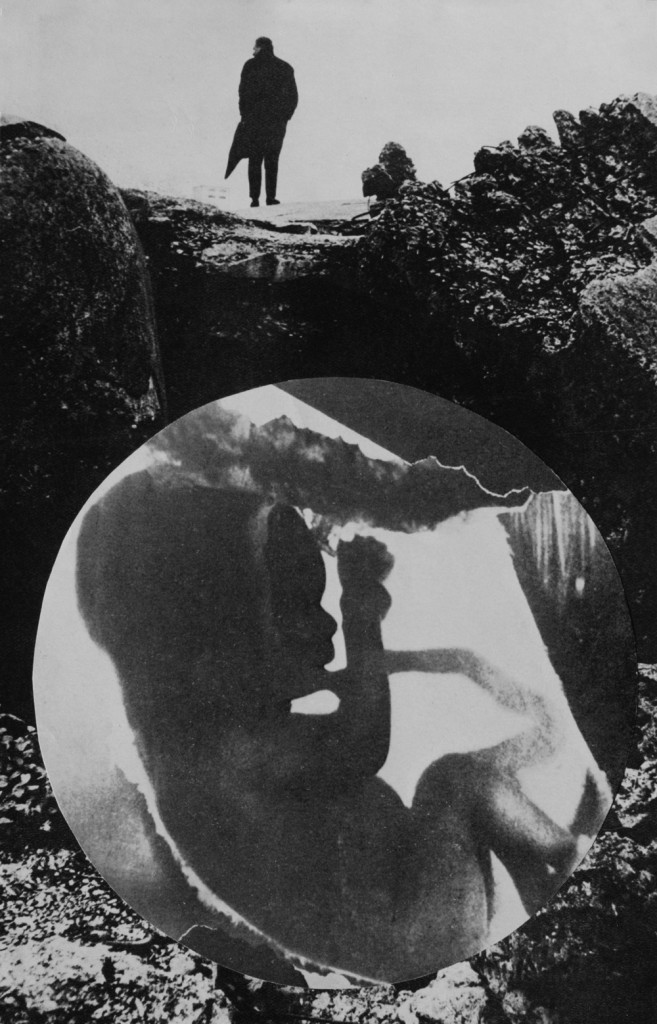

Why not admit it outright: I’m lost. The flood has come, I’ve been broken on the frame of the pictures, drowned in the digital vomitorium, I don’t know what else might be offered now. I don’t know who I am. I try to find my hands in my dreams, so I can sleep lucidly, but as soon as I raise my arms, it seems these hands belong to someone else. Whenever I’m lost I like to turn back to the words of the father, the authority, the law, in order to steer me further into the oblivion I’ve been getting high on lately. So I reach for Walter Benjamin, ubiquitous pole star for every serious media avant gardist, and listen again to the difference between getting lost, and losing oneself. Please let us separate out the qualities of being lost the way an interior decorator would look at a field of shimmering beige paint chips and see a universe of differences. WB writes, “Not to find one’s way in a city may well be uninteresting and banal. It requires ignorance – nothing more. But to lose oneself in a city – as one loses oneself in a forest – that calls for quite a different schooling.”

School

I wonder if there could be a school where I could big up the muscles that would assist me in becoming lost? Imagine an institution of higher learning dedicated not to the practice of knowing, but to not-knowing, or the suspension of knowing. This seems a radical proposition, something to warm the zen maestro’s heart for instance. Or even the hearts of those who are presently at work running movie festivals, and more than that, to those, yes, especially and exactly those who choose to make and watch and entertain the notion of what has been variously named experimental, fringe, avant-garde movies. Because these movies are designed exactly so that one can be lost. Perhaps in absence of Benjamin’s school, they have taken up the call. Where else can one go to be reliably lost, disoriented, unseated, but in the presence of a fringe movie?

Most movies work hard to organize sights and sounds along a trajectory which create a common cause and shared understandings. They don’t call it a thriller if only one person in the audience is thrilled. Though of course there is spillage, even the most canned rehash might include a moment of real looking, or something gone awry, a mismatched eyeline, a hand gripped in tension when it should be relaxed, some telling clue that opens, for an incendiary moment, the interior life of the unfolding scene. And this dizzying moment of unwanted and unexpected revelation takes place for those with eyes trained to see it, for any interested in the fathomless mystery that lies at the unspoken centre of a face, every face, young or old. And once this mystery is glimpsed, even in the half light, even for just a moment, it may become a fragment that can be added fruitfully to the other fragments that will come to be named as a life. My life.

Fringe movies take these unexpected encounters and create a genre out of it, though that seems already oxymoronic. How can we create a school of being lost, a form and framing for the unexpected, for all that actually exceeds the frame? Or to put it another way: how can we consciously produce the unconscious?

Artist

Perhaps one of the jobs of the artist is to convert the known world into the unknown world. To take what might be overlooked (oh, I never thought of it that way), or underlooked (you mean it was there this whole time?) and turn it into an object of contemplation. And the prospect of this viewing isn’t about more grasping and coming to a final thundering revelation. These aren’t how-to lectures. The wash of these pictures – too many even in a single short movie to be fully comprehended and recalled – bypass the usual circuits of safe distance and negotiation, and plunge us into a state of not knowing. In a culture that treasures answers above all – just do it-isms scream at us from every sneaker – here is a place, at least for those festivals that dedicate a portion of its showtimes to fringe movie pursuits, where not-knowing can become a public practice. It’s something that we can do together, like singing in a choir. Dancing in a club. When we tune into the fringe movie frequency, we find ourselves, again and again, face to face with a radical subjectivity, rendered in pictures and sounds. And if the work is good, if the reach is powerful, then there will be something ungraspable about the experience. Something in these fringe movies exceeds our abilities, our capacities, to comprehend. And instead of being frustrated at not being to follow the plot, we are relieved of our literary duties, and are able to hold this place of not-knowing. Of being lost.

Mother

The question of holding is ringing here, ringing all the way back to the fabled English child psychologist Donald Winnicott who aimed to remodel psychoanalysis after the mother-child relationship. His careful observations of post-second world war parentings led him to believe that the question of holding is central to every child’s development. Physically holding a child is one thing, but there are other ways that parents hold their children, for instance, by keeping them in mind, by being near without trying to guide or control the child’s experience. It is in this state of being lost, but with a reassuring guide close at hand, that the child is freed to plunge into unintegrated states, trying on different aspects of their personality, or behaviours that are going on around them. The fringe movie holds a place for its audience in much the same way, while the dramatic movie is like the controlling parent. Here, look at this. Play with this toy. Pay attention to me.

The fringe movie again and again presents itself as a field of possibilities, and then offers that picture back to its viewer as a model for the self. Not the lonely path of myself, or the royal road to the answers, but a field where viewers are invited to wander. Every viewer makes their own way, creating their own film – this is the radical democratic ideal that underlies the exhibition of so many fringe movies today. They require an active spectatorship, an audience busy working with the fragments on display and stitching them together, each in their own way. Meeting the life of the movie with their own life in order to produce unforseen results.

Book

When I read a book I download it to my reader, or else I hold that mass of converted lumber in my hands and turn the pages. I read it in my own time, usually not all at once, I thread the experience of reading into the warp and weft of my living. The book made language a private matter, it removed the necessary performative function, the dramaturgy of display, and turned it inwards, imagining that its readers would be possessed of an inner life, like the book itself. As the saying goes: you can’t tell a reader by its cover. Yes, there were covers and cover stories, things that needed to be covered up, there were insides and outsides, the technology of the book was responsible, in part, for the creation of these psychological divisions.

A similar trajectory might be noted for movies, which began as public display items, freakish novelty events even, but which have turned increasingly, in the past couple of decades, into a home consumer model of consumption. At first there was the revolution of the portable movie, one which could be cheaply rented and brought home, and now of course there is the ever widening portal of the internet. There is no longer a necessary component of going to see the movies, instead, the movies are already there, already here, waiting on a server to be endlessly reviewed. This is the trend, the habit momentum of the past few decades, and movie festivals tend to operate in the face of that inclination, no matter how many interactive computer massaging nodules the festival provides. Festivals still demand some old fashioned going to the movies, and this produces a signal difference in the modeling of subjectivity. Not to mention the quality, could we call it the flavour, of loneliness being offered.

Lonely

On the computer I am happiest alone while feeling the lightest of all possible touches via a steady stream of text messages, and facebook status update, one line emails from friends. Being on the computer is like joining a herd of geese that are oh so lightly brushing one another’s feathers as they step on by. There are no real conversations, no depthful encounters, instead, occasionally a heartful monologue exchange of quacks, but mostly, the temporary diversion of the soft brush with its small questions, whose real function is simply to state: I’m still here. You’re still there. These soft touches provide a close monitoring of geographical traversals. Where are you? What are you doing now? Bentham’s panopticon has found its ideal form in the cell phone, as we busy ourselves telling others where we are and who we are, as if we would lose our identity without these incessant reminders. Have we become so fragile, shattered in the mirrors of our proliferating technologies? I pass phone users on the bus as they announce, “I’m on the bus!” And in front of the bank they proclaim, “I’m in front of the bank!” And in line-ups near and far they insist, “I’m in a line-up!” As if they can hardly believe it themselves. As if there was no self to believe in after all.

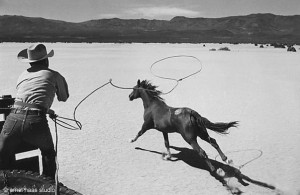

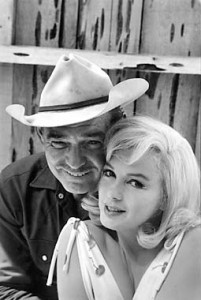

I am thinking of the scene in The Misfits (is it?) where Marilyn Monroe – the last woman in America, the rest have been shipped to Russia as part of some cold war exchange – stands and watches the endless boy-men rope wild mustang horses down to the ground. The cell phone’s locational announcements (“Here I am!”), the endless trivia spewing that comprises so many of these phone calls – “I’m in the produce aisle of the supermarket, did you want grapefruit or cantaloupe?” – aren’t they like the ropes tying down these once wild horses of the self? Or the woman who sees herself in these horses, the one who dreams of the wilderness that might have once grown inside her, before she was only blonde?

I saw this movie in the cinema, where I walked in with all the others so that we could be alone together. I am private, becoming a private person, learning about my privates, in public. What a delicious loneliness this is. It is a loneliness I share with all my fellow cinephiles, all of us craning upwards into the flickering light of the room that is just large enough to hold our dreams. The pictures are so large, larger than life, and my eyes are so small. I bring these pictures close to me, I take them in and receive them, and I do this by making the very large into the very small. I am close to them, absorbed into the picture plane, and rediscover in this reassuring darkness, the old childhood game of fort und da, as Freud named it, of here and there, of near and far. The movie is made up of wild mustangs, and glamorous divorcees and western ranches. It is another life, far away, and it is my life, right here. I am those wild horses, and the men who capture them so they can be sent to the slaughterhouse. I am the man who owns the slaughterhouse, and the other one who sets the horses free so they will never arrive at their destination. Of course, I am also the horses. In this movement between fort und da I never finally arrive, I am in transit, and this is something I can’t announce on the cell phone, which needs always an exact location, a precise point on the map. The old cinema, and the new festivals dedicated to the old cinema, do not exist on maps. I am here and there. I am Clark Gable and Marilyn Monroe. Kissed and kisser.

The Third Person

What does it mean to speak in the third person, to speak about us? What I used to think it meant was that everyone looks in the same direction, that we all nod in time, that we’re all on the same frequency Kenneth. But this is the great leader (left or right, no difference in form) understanding of the third person. This is the old world, heroic model of the third person. Of us. But as the scientists will tell you, what ensures a healthy forest is not that every tree is the same, what allows an ecosystem to thrive is diversity and difference. What makes the festival so beautiful is not that it shows the same movie over and over again, but that it celebrates a fantastic diversity of makings. The festival is a model, a modeling, of diversity. A modeling of democracy.

The festival demonstrates to us that what makes our group strong is not that we are all alike, but that we are all unique and singular. In fact, the festival points out that it is our job, even our duty, to fulfill our uniqueness, in just the same way that these singular and unusual movies celebrate their eccentric seeings. Each of the festival’s fringe movies observes a certain kind of scene. And sometimes that scene is very small and circumscribed. It looks so private. I wonder if you can feel in this private place, a place that is dedicated to the way one person is absolutely distinct from anyone else around them, the necessary beginnings of the third person, the beginnings of us. It’s when you are being most fully yourself, that you bring to the room the necessary conditions for the third person.

Maps

Getting lost. As someone who has never learned how to drive a car, miracles are only a driver’s seat away. How do drivers manage to make all those decisions, knowing what roads to turn onto, and which ones to avoid? They must have maps inside their heads, some deep sense in which the city we live in, lives inside them, and unfurls in the hyper time of driving. I reach out my right hand and nestled in the palm is the other side of the city. The highways and side roads are my nervous system. That’s why my running shoes make that crunching sound when I step down too hard, I have the whole downtown grid gathered up in my arches.

I don’t have these interior maps, so I am getting lost all the time. I can even get lost in the same way, on the same street. It’s a special talent I haven’t found the means to market yet. Just a question of time, though, before this inclination becomes a cash cow, just wait and see. People will grow tired of getting to where they want to go. One day they will decide they only want to get to where they don’t know they want to go, and then they’ll have to hire someone like me to help them lose their way.

David

My friend David drove up to visit last summer, and asked if we might stroll around the islands that are parked off the coast of Toronto. He brought along a serious movie camera, the kind that rolls off emulsion in large lengths, well, it was considered large at the time, brave new cameras like these made it possible to create a single shot that would last as long as ten minutes! Eternity in other words. We step off the boat onto the island and head north. It seemed like he was looking for something without quite knowing what that something was, and I knew better than to ask him about it. It was so fine simply to be in his company, to be hearing the leaves whispering songs, the grasses rubbing songs, the water rising songs. His ears are so fine that he can hear the solar fires hissing on the sun’s surface, coronal ejections they’re named in the trade, and when they occur he just looks over at me and nods. The fire is on fire. What’s beautiful about listeners like David is that he grants you the gift of his attention just by being in the neighbourhood. When you get up close to him you start hearing what he hears, all of a sudden what seemed like noise turns into something necessary and rhythmic.

We arrive at last at the far end of the island, on a wooded boardwalk where David begins the long and cumbersome process of setting up the camera. The three legged support needs to be drawn out, and the device cleaned again, the lenses wiped and rewiped, the delicate sprockets threaded into the path. This is the place. This is the spot. He’s driven up here, five or six hours at least on a trudging highway, across the border, and then we’ve walked for the last hour, here and there-ing. This driving and walking is the approach David makes to arrive at this place, this spot. I should make clear that this place is not possible without the approach. The approach is what makes the picture possible.

The camera is pointed out to the lake, there are rocks forming occasional promontories but mostly sky, a great clear expanse of sky that is slowly darkening as David’s patient preparations go on. When he is finished, when everything is ready to go, he crouches behind his new child of a machine and lets the camera run. The film moves slowly, regular speed is 24 frames per second which makes a steady hum, but David is rolling at half that rate, so the sprockets sound light and delicate, like someone playing their favourite note on a xylophone over and again. It takes twenty minutes to serenade the filmstock through the gate, and as the film moves the sky is moving, and the water is moving, and the light is moving. At last, the xylophone sounds break off, meaning the film has rolled off its core and is fully exposed. David shuts the camera down and we pack up and begin to walk towards the middle of the island. Five minutes into our stroll the entire scene before us shifts into an unearthly reddish glow. A shock of red covers everything and we look at each other, and then I realize why he’s driven all this way. We stop moving, awed by the sight of this ordinary and everyday miracle. Of course this delirious offering was supposed to wind up on David’s film, and he was minutes away from touching down. He had made a long approach, but needed to wait just a little longer. Naturally he was travelling on hunches and instinct, and he was leaving tomorrow so there would be no redos or second chances. Besides, he had only brought one roll of film. He had no regrets, or at least, none that he announced. We had stood witness to the thing itself, we had seen the movie he sensed might be out here waiting, even though he wouldn’t be able to bring it back for anyone else to see it.

Unscheduled

While most festivals imitate mothers who enjoy force feeding their children, some remain admirable in their restraint. Like the festival in Vila do Conde, for instance. There are no movies shown in the morning, because the festival’s fraternal tribe understands that it is necessary to make an approach to the image. The space before the picture makes the picture possible. The morning is part of the night, it is the exhale of the night, just as David’s long drive made his sunset seeing possible. And so there are luxurious mornings in the Portuguese sun, and a quality of time that is neither this nor that. It is an unprescribed and unrehearsed time, in other words, a fertile and necessary prelude and seedbed for the pictures that will come. This is where the real work is being done, so that the pictures will have a place to settle, stomachs are emptied so they can be filled. Imagine an event that includes unscheduled time, imagine taking a time out in the middle of a civil war, or the deciding world cup game. It is so compelling to make a case for filling time, for doing something, and so difficult on the other hand to make an argument for not-doing, for not-knowing. And yet.

Betrayal

Perhaps it is time to speak of betrayal. What would a festival be without a heady dose of betrayal? When we betray someone, or something, the commonplace is that we are letting them down, that there is a received opinion, a fixed idea, that is proven to be false. Every good experimental movie is a betrayal, in this sense. It asks us to leave behind our certainties, the people we used to answer to, the firm convictions we held when walking in the door, and surrender to the laws of a new and temporary science. Not a science dedicated to the establishment of fixed and unchanging laws that will hold in every instance, for all time. But what Roland Barthes named a science of the particular. A science which creates laws that hold true for a single instance. Like yourself. In order to change, in order to step out of the ruts and routines of the person we like to name as ourself, it is often necessary to betray that self, to betray something of one’s own history, to speak and act outside the range of predictable responses. In other words: to invent. Each experimentalism invites the viewer to invent themselves in a science of the particular. Each of these eccentric and idiosyncratic seeings creates a new local instance of time management, along with a new language, and as audience members, alone in our newfound collectivity, we are summoned to the dance.

“A tough life needs a tough language – and that is what poetry is.” Jeanette Winterson

The Couple

And what of the couple who met at the festival? Their every word says yes and no. Every movie they are seeing together does the work of the third person. Will they ever learn how to say us? Will they ever be able to say, “We know, we would like, we think…?” Will they eat cake one day together? Of course they will, and then they won’t. The festival ends in a miasma of fog. Every plane is grounded, and there is a long wait. What a delicious thing it is to wait. The horizontal time, the small shared suffering, it is all designed for them, expressly for lovers. He leaves his bag on one of the small busses that ferry passengers onto temporary staging platforms of the self, and then there is time to retrieve it. Around them scrums of angry business travelers are arguing and shouting into their cell phones. Every one of them announces, loudly, so that the airport shakes with the understanding. “I’m at the airport!” But the couple don’t mind. They are not yet in the adult world. They eat sandwiches and apples and talk in a newly quiet language. They fly to a nearby city on the smallest plane ever invented, and then there is more waiting. They discover another secret: they love to wait. There is nowhere else to be. They love this place in between places. They thrill to the possible identities, the people they might be becoming when they look into each other. The beautiful words fall out of her effortlessly, she speaks of her father, the shoes she used to walk in, the way the sand reaches up along the shore to touch every part of your skin. The horses have been set free. The slaughterhouse is empty. The festival is over. They are going home together.