Nomination Statement

written in August 2017, revised in the next 2 years until Jorge received the award.

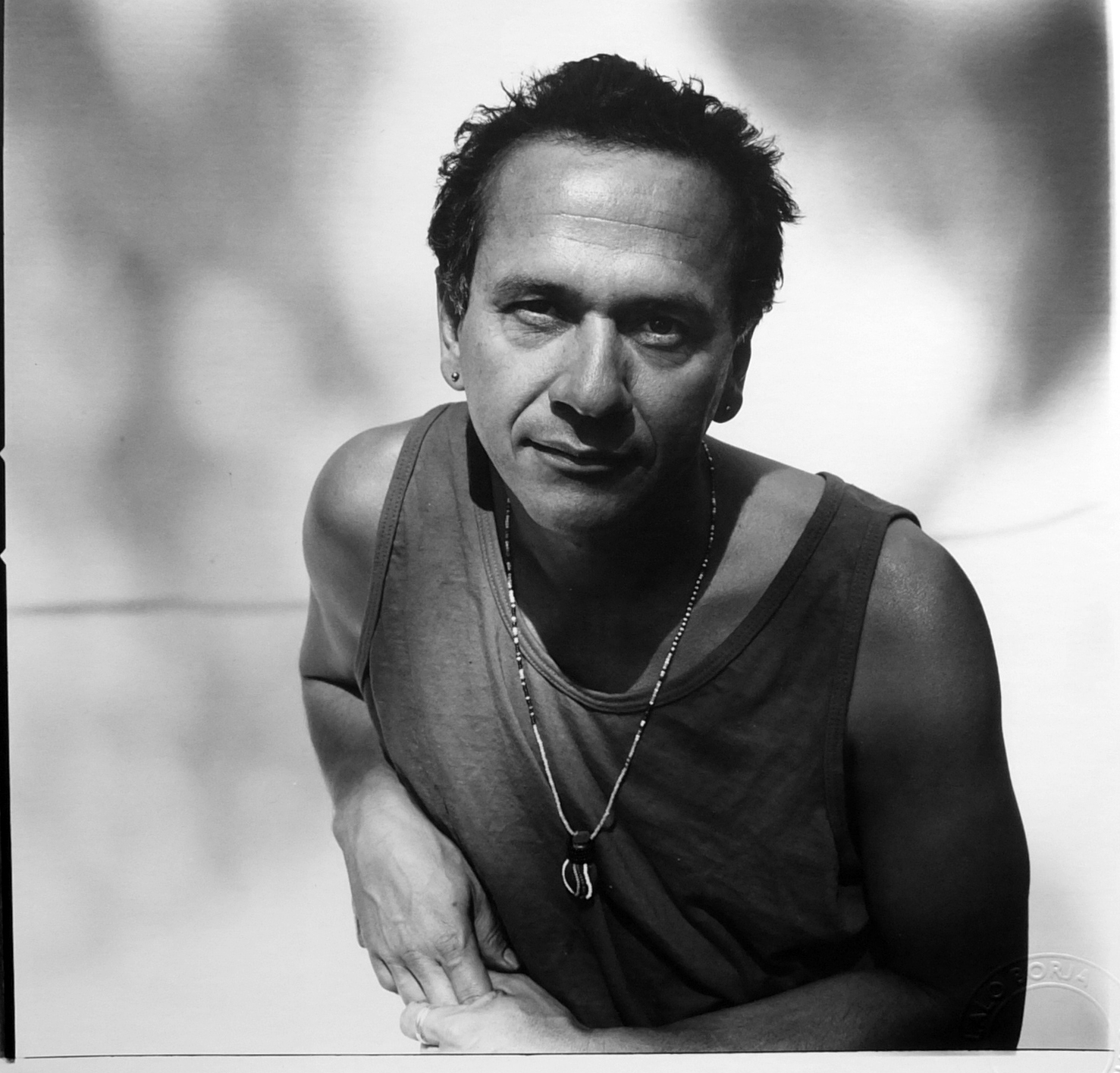

It is with enormous pleasure that I nominate Jorge Lozano for a Governor General’s award in Media and Visual Arts. Jorge Lozano is not only a national treasure, he is well-known and respected in the international experimental film and video art scene. His widely acclaimed work has established him as the most important Latino-Canadian media artist working today.

“For the last four decades, artist Jorge Lozano has been prolific in his production of films and videos notable for their social and political engagement, a strong sense of formal invention and aesthetic rigour. From his single-channel works to his docu-installations Lozano builds unique and compelling structures to house his portraits, giving them a form that assures they stay in our memory long after they are viewed. From the streets of Toronto to the hillsides of Siloé, he serves as a generous and intelligent witness, recording the accounts of remarkable individuals who remind us of the many voices that remain unheard.” Kate MacKay, POV Magazine

A treasure of the international movie art scene, Lozano has made more than 130 films and videos. His restless visual inventions emerge from a period of super 8 activism and personal video interventions in the 1970s. His fiction films have been shown at Sundance, TIFF, festivals in Gramado, Recife, Rio, Guadalajara, Los Angeles, Mar del Plata, Marrakech, Warsaw, Pusan, Sofia, Telluride, Thessaloniki, and many more, though his preferred mode is formally inventive and visually witty shorts, documentary-based work where new identities and startling semiotic formations blend to produce wholly original forms of artist’s cinema.

His contributions to the field are multiple. He has managed to insert a racial discourse into the white experimental filmmaking canon of North America and Europe. He has brought together radical forms with radical content—consistently finding new ways to bring lineages of formal work into the lives of marginalized subjects rarely seen in artist’s movies. He has refashioned the form of the political documentary, using expanded cinema and multiple-screen sculptural installations.

Jorge Lozano states, “The portable video camera was developed by the American military so that it could be used as surveillance and recording equipment during the Vietnam War. In our hands it became a tool of resistance that helped transform our perceptions and aesthetic concerns. With the portapak we started to understand the mechanisms of bio-political technology used to control populations by regulating information. We had to be realistic, and demand the impossible.” Now Magazine

Lozano was ahead of his time and pointed the way for future generations of media artists, finding new forms to disrupt and make visible the unmarked and invisible privileges of whiteness. Along the way he experimented self-reflexively with forms in order to address power relations that shape the production, reception, and mediation of race representations.

For instance, in Jorge’s early work The Three Sevens (1993), each section opens with an Anishinaabe elder speaking and singing. She is a reminder of the earliest keepers of the land, even as a roomful of immigrants vie to make a new home in Canada. But whose Canada will they arrive in? Reframing the question of displacement and power through an Indigenous lens (the artist himself is part Indigenous (Paéz), part black, part white) the suite of stunningly photographed mini-portraits that follow show individuals fleeing violence and (re)forming communities. Questions about who belongs here and what accommodations are necessary run through the movie’s 21 1-minute scenes, as these new citizens try on new identities, haunted by photographs of disappeared relatives, invent new lives.

In Land(e)scaping (2009) we meet Jessica Morales, a lesbian who is forced to leave El Salvador because of homophobia and violence. She is presented in a series of split screens filled with hills and highways, lines of flight and markings that score and divide the landscape. In El Salvador her property is destroyed, she is beaten and her life threatened by a member of the state military. The imperfect storm of sexuality, gender, militarism and state power once again resides in the body of an immigrant, someone who has become a refugee in her own country, and is then forced to flee. The movie is a way of granting “a voice to the voiceless,” redressing the power imbalances that she has experienced in her own life and the life of her country, which has drawn borders around gender and sexual preference as well as national identity.

His work has been met with critical acclaim from many quarters, as exemplified by the Canadian Film Institute’s Tom McSorley: “The prolific and protean work of Jorge Lozano both resides in and expresses a liminal state. Ranging from non-fiction to experimental to installation pieces, from prosaic to poetic to polemical, his remarkably diverse output explores and crosses much terrain: geographical, cultural, emotional, political, cinematic. Chronicling the complex and various pathways taken from his native Colombia to Canada, from south to north and back again, the contours of Lozano’s own ‘in-between’ sensibility are strikingly rendered in a welter of impressive films. Seldom has a Canadian media artist straddled so many borders so beautifully and so bravely. Crossing and re-crossing territories, Lozano’s work brings us to many thresholds of perception, many moments of recognition.”

In Jorge’s work we are always asked to see how the border, the territory, is being re-marked. Sometimes this border arrives as a particular pressure used by the state to mark its citizens, sometimes the border designates gender or economic status. He was one of the first media artists in Canada to take up transgender representations, which he has complicated across decades of engagement to produce increasingly sophisticated work. Samuel and Samantha (1992) remains a touchstone. Toronto’s “gay ghetto/village” was clustered around Church and Wellesley, and many in the white (dominated) community discriminated against Latino gays. As Samantha states in the tape: “Drag queens and trans aren’t even considered gay by many in the village.” The policing of identities and the territories that those identities were permitted to occupy are eloquently narrated by Samuel, who transitions and becomes Samantha.

Samuel and Samantha premiered at the Images Festival in the Euclid Theatre. Across the road, the Pantera Rosa (Pink Panther) club had opened just a week earlier, providing a new home for queer Latinos and drag queens. After the packed screening everyone went across the road, and a venue that had been underground and almost exclusively Latino became known, embraced and frequented by many in the gay community. This venue was discovered via Jorge’s Samuel and Samantha. Later the same year, the movie was shown again at the same venue, this time during Inside Out, Toronto’s LGBT movie fest. The after-screening party was held at El Convento Rico, a few blocks west of the theatre, and this party put Rico on the city’s gay map. It quickly became a home for drag queen beauty contests and late-night queer celebrations. East of Pantera Rosa, the owner of El Convento Rico opened Tacones (High Heels), and because of these three clubs this strip of College Street was redubbed “the pink triangle.” These clubs dislocated and relocated Toronto’s white gay village, now there was a gay Latin satellite. Jorge’s aesthetic reformations have always been tied to political formations, as he works to bring unseen faces to the screen, and insists on multiple identity readings. For his sterling contributions to community/neighbourhood building, Jorge received awards from Hola, the gay Latino association, recognizing and expressing appreciation for his work.

Jorge is one of earliest and most consistent chroniclers of gay Latino life in Toronto during the past decades, showing up at marches, demonstrations, rallies and nightclubs. His ongoing community reports appear in many movies and installations, from the billboard remix of In the Body of Knowledge (1981), the collage-essay Does the Knife Cry When It Enters the Skin? (1984), the Nicaraguan revolutionary ode Letter from Fatima (1984), community soapbox What’s Going On? (1990), anti-identity audio-visual graffiti proclamation Samplings (1990), the queer narratives of Brief Chronicles of Glia and Luna (1992), the arch-feminist Pacquita La Del Barrio (2000), poet bio-short Pedro Pietri: Puerto Rican Obituary (2000), the performative lesbian idyll of In Deep Skin (2004), the irreverent trans portrait Lola’s Art (2009), and Situations (2012), a triple-screen condensation of public resistances. Unlike some of the more strident work of his peers during the same period, Jorge’s movies are both aesthetically sublime and politically sensitive, a major bulwark and support for a community that continues to be politically active.

Cultural critic Deborah Root writes: “Lozano’s speaks in many tongues, he is constantly compelled to critically rethink and redefine paradigms set in motion by centuries of colonialism and marginality. He is something of a magician, creating new ways of seeing, new realities… By writing himself into the middle of The Three Sevens, as he does in much of his work, Lozano allows us to see how he is implicated in the story he is weaving, as indeed we all are. And the implications cut across space, as someone coming here to flee political violence carries with them a particular kind of trauma, and a fear of deportation that may well have death as its center.” Splintering Time, Fragmenting Space: The Video Works of Jorge Lozano, catalogue

TIFF programmer Chris Kennedy notes: “The last decade has been extremely prolific for Lozano: half of the nearly 100 works in his videography were made since 2005, and he has expanded from single-channel work to installation, most impressively with the eight-screen MOVING STILL_still life, which premiered at the Ryerson Image Centre in late 2015. Part of this explosion of work derives from Lozano reconnecting with his Colombian homeland through frequent travel to his birthplace to lead youth media workshops, which has stoked his desire to tell stories from the impoverished areas of a country still suffering through a long-running civil war.” TIFF program notes

Not content to simply make work, Lozano is a community builder. He co-started the aluCine Toronto Latin film and media arts festival in 1995 with Sinara Roza. Canada’s longest-running Latin film festival celebrated its 20th anniversary a couple of years ago with a massive Jorge Lozano retrospective, as aluCine continues to provide a two-way portal between Latin American artists and Canadian residents. In the earliest years Jorge ran the festival out of his living room, and arranged screenings and tours throughout Asia and Europe. His dedication to expanding the dialogue between local and South American artists culminated in a series of brilliantly curated programs that have traveled around the world, bringing necessary exposure and visibility to ignored bodies of practice.

Lozano has also helped innumerable artists-of-colour to create movies, acting as camera operator, musician, sound recordist, editor, producer. His small cache of low-fi gear has been distributed widely across the city, and his name appears again and again in the credits of movies made by others, as his DIY spirit inspires and animates those around him. The list of artists he has helped along the way reads like a who’s who of Canadian media artists of colour, such as Julieta Maria, Alexandra Gelis, Lina Rodriguez, Guillermina Buzio, Ulysses Castellanos, Juana Awad and Alejandro Ronceria. Once again, this demonstrates how Lozano not only supports existing communities but reinvents and expands them by introducing new perspectives and artists, emboldening new generations.

Additionally, for the past two decades Lozano has organized youth workshops both in Canada and across South America. Typically working with homeless kids, economically marginalized and struggling with racism and criminal records, he has developed new forms of pedagogy that empower youth through self-representation. Refusing traditional hierarchies of teacher and student, he has helped hundreds of first-time media makers create personal, socially conscious works, many of which have gone on to great acclaim in festivals around the world.

Jorge Lozano is an artist who continues to reinvent his forms, his ways of living, and his community. He is forever translating his thoughts and encounters into media moments, deeply concerned with the art of asking questions. Why this gender? Why this desire, this neighbourhood, this poverty? The artist’s commitment to experimentalism is animated by the necessity of these questions, which are forever opening, like the artist’s heart. While his importance and centrality has long been recognized outside the country, it’s my hope that some of this acclaim may also be accorded at home, where he has done so much to energize the field of artist’s media.