Priceless: An Interview with Helen Lee

Originally published in Practical Dreamers (2008)

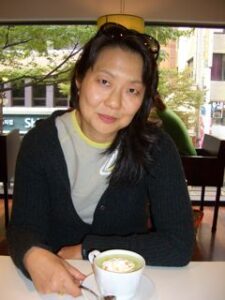

She was supposed to be far too famous to be in a book like this. HELEN LEE! She should have eaten up the director’s fortnight at Cannes, then produced her cross-over hit, before retreating back into a first person cinema which hurts to look at, the way you turn your eyes from certain kinds of beauty. But because she has thrown her lot in with the moneylenders and the shell gamers and the ones who write I promise notes on festival napkins she is living in Korea now, with two kids and a husband who looks like a movie star, plotting her next move and her next perfect dinner. Priceless. She was supposed to be priceless by now, and who knows, by the time this book’s come out she might again be the name on everyone’s lips, another of those endless icons of desire that we are all secretly busy waiting to become.

Like Jeff Erbach, who appears elsewhere in this volume, she can’t pick up a camera and go wandering out into the streets in search of the good light and a face that looks back. Instead, she needs a script and a director of photography and a crew to realize the pictures that are lying inside her. These capital intensive efforts mean that picture making is a slow and sometimes cumbersome affair, and one which involves waiting and organizing and turning yourself into a personal bureaucrat. She has handled all that on small scales in her work to date, and produced a suite of glowing promissory notes which elegantly lend stories to a post-colonial condition. She is one of the smartest filmmakers I’ve ever met, rousing herself out of a temporary haze of shoe stores and insider food jokes to lay down incisive and unsettling critiques. The pictures which have already arrived and the pictures which are in the midst of being born, they cut to the quick. They are somehow always unexpected, as if one were ambushed by a cool beauty, the steady throb of minor key glamour, the raw intelligence which bursts out of the background details. Will she or won’t she?

Helen Lee: To announce that cinema itself, at root and centre, is a white male enclave seems to be stating the obvious—and people don’t like to hear it, not then and not now: how boring, oh do we have to bring that up again, get over it already. To have the same sentiments reinscribed in what’s assumed to be a more progressive, now-rehabilitated environment of indie experimental makers, well it’s a bit galling isn’t it (as if we expected better from our peers than the more commercial arena of feature films)? What being male and white (gay or straight) endows is of course not a natural aptitude or in-born talent for cinema but rather a feeling of enfranchisement, that yes I’m able to go out and make movies as if it’s my right. Thank god there are some women, and increasingly more and more, who believe they are equally entitled. I don’t think anyone was ever happy with the term “people of colour,” but we created that space for ourselves, pried it open, carved it out, squatted it and made our own uses of it.

My illustrious teachers at NYU and the Whitney were wondrous, and we students were tadpoles in a very deep pond. At the same time, nobody was saying anything exactly about my experience in the Asian American world, the way I’d like to see it–which is more sideways and askance–in the critically challenging way that was exciting me at the time. In that sense, criticism and theory (Stuart Hall, ideas of Third Cinema) came slightly before the watershed moments, and prepared the way. But very quickly, they arrived hand-in-hand (Trinh T. Minh-ha, Sankofa and Black Audio Film Collective), inseparable and stronger for it. The most compelling artwork, for me, is almost always socially engaged.

Mike: In his seminal 1991 essay Yellow Peril, Paul Wong writes, “In general, few Asians venture into the field of contemporary art practice. Those who do, make fully assimilated “Eurocentric” work or choose to work in traditional forms or commercial art areas.” How did you get hooked on movies, and how did you avoid (or did you?) the Eurocentric banalities Wong warns against?

Helen: Doesn’t everybody love movies? I had a steady diet of 70s TV kids shows and California sitcoms, graduated to watching b&w oldies and Duran Duran music videos, before becoming thoroughly semioticized through years of film theory. Seriously, that’s the narrative. And ringing through my head was hearing about Kathryn Bigelow and how she had to “unlearn” everything she was taught in the Whitney program in order to make her Hollywood films. That said, I’ve hardly watched any television over the past twenty years, and narrative filmmaking is still an unending puzzle for me. Writing a script is such a mind-crunch, especially when you want to engage in genre but not be entirely subsumed by it (those reflexive experiments hardly ever really work, do they?). I had an early interest in meta-narratives especially those with a feminist perspective (Chantal Ackerman), even when these perspectives are not obvious (like in the fearless films of Claire Denis). In the fifteen years since Paul’s essay, the ground has definitely shifted and there’s certainly more Asians artists in the sphere. To lapse into arguments of Eurocentricism even seems quaintly outdated, glad to say—everything’s become so much more decentralized, and it’s widely acknowledged that some of the best cinema comes from other parts of the world. Korea has also been “discovered” for cineastes and lionized at international festivals and popular in arthouse circuits. But there is always Hollywood as some kind of global standard, and the obsession of box office statistics as daily news. The making of feature films, especially in English, will always be circumscribed by this context, between the American behemoth and European felines. Which is why Canadian cinema fares so poorly on the screens, even (or should I say, especially) on our own.

Mike: There is an abiding stress placed on women around the question of balancing a ‘work/artist’s’ life with duties of family and home. A friend of mine complained that since she had a child she was no longer taken seriously as an artist, at least not here in Toronto. As someone recently hitched, with two kids as part of the deal, could you comment on the continuing joys and pleasures of balancing a world of self-made pictures with everyday demands of those near and dear?

Helen: Haven’t been able to learn that trick yet, Mike. That uneasy, if downright ill-fitting match of artistic aspiration with motherhood. Perhaps they are equally vital, creative endeavours? We all know about Jane Campion’s work after becoming a mother—whatever happened to that edge and visual incisiveness, her adroit direction—and I say this as someone who was her biggest fan. Something about focus, I imagine (no pun intended), and the intense burning passion and extremely hard work that attends both filmmaking and raising children. I know that to pursue film properly everything (and I mean, everything) has to go by the wayside, including personal relationships. Men can put family on the backburner as they go into production, but it’s harder for women who usually carry the domestic burden on their shoulders, to ignore the laundry, kitchen mess and hungry children. Some of the most successful filmmakers have extremely supportive spouses (i.e. wives), though I don’t know many women directors with kids who have been able to muster the same support. Even the dance of development, when financing is in limbo and endless meetings with various people you want on board your as-yet-unrealized project, combined with creative uncertainty and constant script changes, can only be overcome by 110% energy plus luck, and that can be a bit difficult when you have to be home by five for the kids. The domestic juggle alone is exhausting, never mind adding the more than full-time occupation of being a filmmaker. Right now I don’t feel like a filmmaker anymore. Though believe me, I am craving to make those cuts, add the sound, recut to make it work, rescreen, cut again… that completely obsessive activity so ingrained it feels like part of the DNA. Maybe when the children get older it will be easier, more in the realm of possibility. Or, in the interim, scale down the projects into mini-movies, little video projects. Somehow I’ll try. But right now I have to go and make dinner.

Mike: What a thrill it was for me to watch Sally’s Beauty Spot (12 minutes, 1990) again, though I’m guessing if you made it today it would be quicker, slicker, its surface a smooth sheen. Which makes me wonder: is there a pitch and speed that “belongs” to each time of making, and do movies both express and reflect that attention? Does the flow of pictured events, even in narratives, provide models of time which we watch so that they can inhabit us, so that we can inhabit them?

Helen: That’s so funny, when I see SBS all I see is how rough, even primitive it is. It was shot on a hand-cranked, non-reflex Bolex camera that I bought at a country auction, with those 100ft 16mm rolls, no sound, and we had practically nothing in the way of lights. I think we shot the whole thing in our pajamas. We’d all roll out of bed and I’d wake up Sally, “C’mon, we gotta go shoot now.” One thing I was preoccupied with, besides the ideas of the film, was the rhythm and pacing, because it was originally done for an undergrad editing class when I was enrolled at New York University’s graduate cinema studies program. (I took it as an extra course because I wanted to learn some filmmaking while studying theory; everyone in the class had to edit something, anything, like found footage, but I thought I’d just shoot some of my own footage to cut together for the exercise.) I cut the workprint on a Steenbeck, with magnetic sound. I think there’s a fundamental difference of time and duration between film and video. It’s a much faster and more expedient process cutting in video of course, cleaner, even sterile. Pushing buttons allows you to cut more impulsively, try dozens of variations, and in the process become confused with all the miniscule variations. With film—and stop me if I sound nostalgic—I think you are forced to think things through more, respond more to a physiological impulse because the cut is physical. The feeling of ribbons of celluloid running through your fingers, or threading through the machine, creates a different sense of time and timing. When you’re fine-cutting you can tweak it to the frame, see those individual frames literally pass before your eyes. It’s a feeling like being inside the text, and being part of its texture—you don’t get that same feeling with video, which offers a feeling of gliding mastery, manipulation and digital dexterity. Despite its anachronistic status, in some ways I think film cutting is a more conceptually sound process, the construction of the film can be more holistically achieved. You can have all these trims of different shots and selects sitting in your bin and then an idea strikes. Some happy little accidents can happen while editing, as you’re putting one shot next to another. The physical proximity and handling of the footage is what we miss when working in video.

Mike: Your movie is, amongst other things, a very intimate exploration of your sister’s body. The beauty spot of the title is a mole just above her breast which she is constantly scrubbing and picking at, we watch her putting her shirt on over and again, rouging her lips, kissing a couple of handsomes. Why did you cast your sister for this role? Was the ‘issue’ of her beauty spot already a point of discussion between the two of you? Did you ever ask her to do anything she refused? Sally’s Beauty Spot is redolent with pictures of Asian skin: the disrobing of Suzie Wong (“Take that dress off!”) for instance. There is a delight in looking expressed throughout the movie, accompanied of course by theoretical hat pins, an erotics of attention which lingers despite (?) the quick witted montage. Can you comment?

Helen: My sister Sally is now seven months pregnant and I feel her pregnancy in a wholly different way than from when, say, other relatives or friends were pregnant. Obviously it’s because of the relationship I have with her body, our bodies, over time, as sisters close in age (she’s two years younger) growing up. Koreans have a term called “skinship” which means the feelings of closeness and tenderness engendered from literally touching the skin, or say a couple on their first date and one of them accidentally brushes by the other’s arm or something. It’s not so much sexual as it is sensuous. I think feelings of absorption, feeling subsumed, and otherwise giving yourself over to the other, is part of it. My sister and I are unusually close. When boyfriends weren’t around (and sometimes when they were) we were still each other’s significant other. (I guess that’s all changed now since we both got married this year.) Just after completing the film, I showed it to a fellow Canadian studying in New York, David Weaver (who was at Columbia and also became a filmmaker), and he mentioned pretty much the same thing, the “erotics of attention” you speak of. And for the first time it struck me how sexualized my sister’s body was in the film! I was so preoccupied with the concepts of the film that the idea never even occurred to me. Although it is a sexualization that comes from a self-possessed, self-actualization rather than objectification, I’d argue. Biographically speaking, I don’t think Sally had any complex whatsoever about the mole on her breast, and I had only a vague awareness of its existence even—it was just a rather convenient cathexis. One of my academic highlights was being able to do an independent study with Homi Bhabha through the Whitney Program, a kind of one-on-one seminar with him when he was a guest professor at Princeton in 1992. Since he was one of the inspirations of the film, I showed it to him. He commented on the mole on her breast as a kind of Barthesian punctum, the peripheral detail that is so telling. My sister, no slouch in theory herself, immediately ripostes, “Hey, no way, the punctum is the stretch marks.”

Mike: You make ample use of clips from The World of Suzie Wong by Richard Quine (starring Nancy Kwan and William Holden). We see Sally watching this movie, as she takes cues for her own life, she offers us a model of picture reception. She is the first audience, and we watch the movie over her shoulder. Or at least part of it. Why was it important to insert the viewer into the frame? How did you come to choose this movie, and how does it function within your film? And how do the complicated exchange of looks “work” in your movie?

Helen: It was important to assert Sally as an active and interested viewer who took pleasure in the images of Suzy, a stereotypical “dragon lady” and “hooker with a heart of gold.” Although The World of Suzie Wong is addled with clichés, it was one of the few attractive mass media images, one of the few images whatsoever, for young girls like us growing up in North American suburbs in the 70s, and this old 1960 film seemed to be on TV all the time. She looks smashing in a cheongsam, her sassy attitude and flagrant sexuality was part of the hook (and even more so if she had actually spoken with the British accent that Nancy Kwan must have had since she was raised in England, how interesting would that have been). So Sally’s viewing provokes a discussion about how we find pleasure in things that are supposedly “bad” for us, in reputably racist images such as Suzie Wong. It upends the rather simplistic argument that only “positive” images are good for us, for the so-called model minority citizens that Asian Americans are purported to be. But then I wondered: isn’t it just another kind of simplistic reflex to position Sally as a viewer in front of the film? And then I realized that film is fundamentally full of simple gestures, basic human responses and behaviours. Sally is no longer ignored or invisible, but rather becomes a “reading against the grain” kind of viewer. Because that’s the only way to look at old films or old pop songs, otherwise we revert to nostalgia and sentiment. We have to invent a new historicity to make it relevant to us, how we live now.

Mike: One of the voices in the soundtrack says “Skin as the key signifier of cultural and racial difference in the stereotype is the most visible of fetishes, recognized as common knowledge in a range of cultural, political, historical discourses and plays a part in the racial drama that is enacted every day in colonial societies.” Do you still believe this to be true? It is rare to hear statements like this made in movies made today, why do you imagine that is?

Helen: Yes, it does sound rather totalizing, doesn’t it? Especially for most of us who don’t see the world in that way, despite the dialects of North/South, white and black (or brown or yellow), master/slave—because history can’t be ignored. But probably class and economics penetrates all this. I mean, practically anyone will work with anyone and put prejudices aside if the money is right. That’s probably too crude or rather jaded. I think in cities like Toronto or New York you’ll find both race-identified clusters and also a cosmopolitanism that tends to elide or mask the conflicts—but they’re there, especially in terms of class (as other places such as Los Angeles and Paris suburbs have found), or obviously in terms of religion (London, the Middle East), and the perceived threat of difference. Everyone likes to believe there’s progress and tolerance, and that education and assimilation are working. But the issue of race remains. It may be parodied in Hollywood, or commodified and niche-marketed, but it’s still an “issue.” It’s not often talked about as *skin* per se because that would be so wrong and retrograde, wouldn’t it? French films that take up race with a heavy skin factor at play, like La Haine and some of the earlier films by Claire Denis (who I immensely admire), seem to be made under the ghost of Franz Fanon and the spectre of Otherness, like it’s an inescapable legacy. No matter how far away from a post-colonial environment we think we may be, we’re always confronting the Other, and in turn, ourselves.

Mike: My Niagara (40 minutes, 1992) opens with home movies taken in Japan. Where are these from? How do they escape the aura of cliché and redundancy that clings to all home movies (which all seem to be made by the same camera person, showing the same family, doing the same things)?

Helen: We shot those “home movies” on Super-8 Kodachrome then transferred to 16mm, a beautiful process that renders super-saturated color and grain you can almost touch. It exemplifies the difference between analogue and digital with all of its scratches and hiccups—a much more “human” look. In a sense we wanted to remake that cliché. I saw the opening sequence as a fantasy, a childhood nostalgia for the main character Julie Kumagai, for whom her mother is an idealized, untouchable figure, long-dead. I don’t know all that many Asians, especially Asians like me who immigrated to Canada in the late 60s or 70s, who took those kind of pictures—we were caught in snap cameras or Polaroids. But it was different for Japanese Canadian/American communities who had been here one or two generations, some of them made those beguiling pictures. I couldn’t resist, at the end of the home movie footage, to steal some thriller genre music (from a 1948 Nicholas Ray film called They Live By Night) to undercut its sweet nostalgia, a foreshadowing of Julie’s sullen, introspective character.

Mike: The clothesline at night with its ghost-like sheets, the snake-like green hose glimpsed in moonlight—you’ve rendered suburbia as a mythical place of beauty and terror. You grew up there, didn’t you?

Helen: And I have tremendous nostalgia for it, despite having desperately wanted to escape it, especially at that time because I was living in Toronto without my family. My parents and siblings had moved to California and then Vancouver (though my sister subsequently moved back), leaving me immediate family-less in my hometown. The situation gave me time to mull over my childhood and upbringing. We shot the film in Etobicoke, in the house that Kerri Sakamoto (the co-writer) grew up in. It was different than Scarborough, where I was raised—a little denser, not as spaced out—but also the same. The safety, ennui and also the repressions lie beneath a pretty and peaceful exterior. The cinematographer, Ali Kazimi, had an idea to shoot these day-for-night shots that would bring a spark to the silhouettes, and evoke loneliness. Now that my existence has been completely urban and downtown the past twenty years I think I look back too fondly on it, even now with all the big box retailers. Of course I could never live there again.

Mike: Throughout My Niagara there is an eye for lingering details. The impulse to stop and admire the shape of a plant takes one outside narrative requirements which are fundamentally paranoid, in this sense, that every gesture, no matter how small, has significance, and that these significances “add up” to a closing denouement, the ah ha! moment. Your movie presents these nomadic attentions as asides, and these two movements of the film seem in opposition. Can you comment?

Helen: That’s so astutely observed, Mike. Because again it was an unconscious process at the time. All I know was I was extremely concerned about these little details and when we were shooting, the crew members (who were much more experienced than me) referred to these shots as “cutaways” and seemed to relax and not care so much about these short set-ups without actors. But to me they were just as important as the dramatic sequences! In fact, there were more of these asides than what ended up in the film, because exactly as you say they were hard to reconcile with the story and tended to hold up the film’s narrative momentum. In that way I felt the narrative had won out over the anti-narrative impulse I was exploring at that time. Those experiments fascinated me, those films by Sally Potter, Patricia Gruben and Chantal Akerman. I thought the film was a “failure” not to fulfill these puncturing effects, these quiet moments outside the story proper that still had something to say. There were similar sound cues in the film, sounds of water dripping, sprinklers, that kind of thing. I think that’s what gives the film its enigmatic character, this sense of estrangement from a typical narrative film, because there’s something else at work. The film ends with Julie serving two bowls of rice for herself and her father, and it’s shot at waist level. There was never a full shot that included her head, or a close-up of her face that would “tell us what she’s thinking.” It was exactly her gesture that was important, the same daily, never-changing, never-questioning gesture of duty and obeisance that ruled her life.

Mike: Each of the characters lives a double life because of their ethnicity. He’s Korean trying to escape the Japan he grew up in, while she longs for the Japan she’s never seen (and hopes to find in him). This double vision which troubles the transparency of representation is typical for makers of fringe movies, which features a disproportionate number of first generation transplants. Their (our) parents grant us an irresistible sense of another world, even as we are busy growing up in this one. Your movie articulates this double vision, both content-wise and in its stylings and vagrant attentions. Can you elaborate on this theme and why it is important for you?

Helen: At that time, in the late 80s and early 90s, there was so much critical theorization around otherness and alterity, postcolonialism, Third cinema, oppositionality, marginality, fringe films… it nearly busted my brain! Here I was in cinema classes studying Wittgenstein and the Frankfurt School and continental philosophy, and I thought I was supposed to be studying film! (At the time cinema studies was concerned about its position in the humanities and institutionalizing itself in the academy.) It was so much more pleasurable and productive, I thought, to try to apply these interesting ideas to making films. So I was extraordinarily preoccupied by these themes, they were there first for me, preceding the filmmaking apparatus and production skills that I learned in conjunction with the making of these films. These projects were, at first, a critical enquiry or investigation, and then a film proper—as if I was making films instead of writing essays. Making My Niagara was so much about the way its characters were seared by marginality, but we didn’t want to portray only that. Their ethnicity and backgrounds were a given (race wasn’t “the story,” so to speak), so that we could contemplate something else about them, their particular foibles and self-projections. I was also obsessed with tracing a kind of subjective cinema, and how to shoot a film that let subjects speak from a naturally empowered position, not as objects of sociological or anthropological interest. Which is still why I am asked, when someone finds out that I’m a filmmaker, “What kind of films do you make, documentaries?” Because if I’m an Asian woman then it’s about sociology first and films second. The challenge is trying to bring a cinematic structure to this “double vision” as it’s so aptly called, wherever that doubling or tripling may take place—on the level of aesthetics (experimental films), gender (feminist films), or race and ethnicity (films by “people of colour”). Don’t you love that line in Miranda July’s film where Tracey Wright’s curator asks about an artist, “Is she… of color?” It’s such a knowing comment about the contemporary artistic cultural environment, isn’t it, along with its jaded, aren’t-we-all-past-that posture. Well no, we aren’t.

Mike: Can you comment on the figure of the father? He is a box maker, able to make containers (which are empty, it’s as if only those at home here in the new world can fill the containers, while he is able to provide the frame, the shape of experience). When his daughter Julie expresses her admiration and accepts one of his handmades as a gift, she provides a bridge between old and new worlds.

Helen: It is that little gesture of offering and acceptance that provides the tiniest suggestion of where Julie’s gone as a character. Otherwise, she’s someone who’s changed very little throughout the course of the film, as tied up as she is in the trauma of her mother’s disappearance in her childhood. I think that may have been a problem for some audiences, that she didn’t change or transform, as is ordinarily expected. We want our main characters to advance themselves, to learn something, etc. Her mother’s spirit still haunts and disables her. Her relationship with her father is a kind of inverse–it’s so everyday, but their exchanges are stilted. The father is the classic Nisei (second generation) character, which is to say, though he was born in Canada, speaks only English and likely spent some of his childhood in the internment camps during World War II, he is still identified by mainstream Canada as a Japanese man. But again, that wasn’t “the story.” I think that’s how Kerri and I approached the script, we weren’t stuck with announcing the character’s ethnicity or racial background all the time. We wanted those histories to be already absorbed by the characters, it’s a part of who they were, and it wasn’t our job or theirs to explain it all the time. In some ways the father is a vacant figure, or rather evacuated from Julie’s life (which is fairly solitary anyways), so they are in that sense two solitudes living in one household. He can express so little, except by giving his daughter one of his empty boxes. The running theme through most of my films is, ironically, the absent mother. It started with My Niagara, and then continues through the other shorts and even my feature film. I can’t really account for this repeated pattern of maternal loss except to say that the figure of the mother is also a symbol of the motherland, the repository for all the cultural longings, memories and projections that remain unfulfilled.

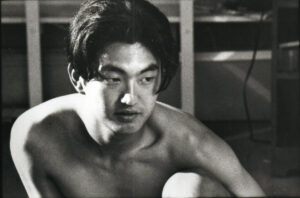

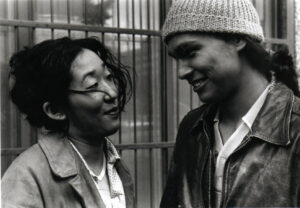

Mike: Prey (26 minutes 1995) is a self-assured drama about Il Bae (or Eileen) who works in the family’s convenience store, and falls in with a young drifter. The move revels in the beauty of its stars, the hunky Adam Beach and beauty queen Sandra Oh. While their onscreen chemistry and acting chops raise them well above the level of eye candy, do you worry that their fine looks present an ideal the rest of us will never manage, and that this frustration will further the cycle of beauty debt and pharmaceutical potions that has extended the reach of capital into every moment of the consuming body?

Helen: Sandra and Adam are hardly beauties of the typical sort, but inherently have stories to tell, a lived-in experience that makes us want to know them. I’d be dishonest if I said they weren’t cast for cheekbones, but more than the physiognomy, there’s a steady gaze that holds your eyes. And most of all, the two had a chemistry that busted archetypes and memories of staid, objectified characterizations. So I don’t think the film presents them as idealized figures in any way. (In fact, Sandra wondered why she had to look so grungy, but it was all in character to say that Il Bae got woken up in the morning with an emergency, and stayed that way all day.)

Mike: Could you elaborate on the title, Prey? This is a movie where every character seems both preyer and preyed.

Helen: When we were in production we had another working title, “Automatic,” but that seemed didactic and cold, while Prey already sets up a kind of narrative in the title, and has a metaphoric dimension. I don’t remember exactly where the title came from—probably from Cameron (Bailey, my partner at the time), he’s really good with titles. In any case, it’s not meant to be literally interpreted. Although there is that section in the film where Il Bae sits down with her grandmother, Halmoni, to watch a nature documentary on TV. This is shortly after the surprise encounter with her semi-naked, now banished Native lover in the same room. Avoiding the obvious, Halmoni remarks on a lion devouring its prey, correlating it with Korean survival, not without nationalistic pride. But then she’s completely oblivious to calling this Native stranger a “foreigner.” Who is foreign, native or other here? The immigrant still trumps the Native on Canadian soil, both economically and socially. In terms of enfranchisement, visibility, and power, it is still, ironically, immigrant lives that have advantages over Aboriginal people. And it’s a sorry state, isn’t it, to be comparing and contrasting oppressions, but these differentials in history, educational and social opportunities, must be taken into account. Factor in the privileges of whiteness and class, and there’s a minefield of difference at play. There are no “white people” in Prey (save the pawn shop owner) who act as a “base” from which people of colour are positioned as being different. And that’s the one thing that’s common in all of my films: we are the “base.”

Mike: Amongst other matters, Prey relates a story of young love (whose desire makes prey of each other). Does love occur only where there is something missing—a deficiency which needs to be smoothed through touch and language? Despite their wounds, both Il Bae and Noel appear to be trying on roles, posing with guns and lovers, sometimes shopkeeper or juvenile delinquent or dutiful family member. How do the pictures which surround them, which they are busy occupying, help or hurt them in coming together? Please forgive this dangerously naïve question, but might your movie also suggest that ethnicity itself can be a pose or position?

Helen: There is a certain amount of positioning that occurs as soon as you place a non-white character on-screen. You automatically do the mental calculus from your position as a viewer—it depends where you’re placed or how you place yourself as a spectator, how you can thus read the character. An insider can have “special knowledge” or assumptions about the character, that means less explaining is needed, or rather a different approach. We already know that back story. Can the same be said of, say, gay characters in a movie? You can only go so far with that logic. Because then we’re relying on generic stereotypes, even as we play and manipulate them. Il Bae and Noel were entirely independent creations, but they are constantly flirting with each other on that edge of race, ethnicity, and gendered expectations around desire. The challenge was to frame it in a dramatic story that seduced you and shook up your expectations.

Mike: Il Bae has lost her mother, Noel his sister, Il Bae’s father has lost both his wife and homeland. Is the displaced place of the immigrant always one of loss, is every gain measured by what must be left behind? Is that why you conjure this geometry of loss?

Helen: I do think the immigration story is suffused by loss, and not only the gain of a new life in a new country. Somehow there’s a conflation of mother and culture in my films, this yearning for cultural connection is symbolized by the lost mother. The relationship between Noel’s loss of his sister and Il Bae’s loss of her mother, tenuously linked in the story, is also a linchpin for their connection–not that they should be defined by negatives, however. They’ve both known sadness in their lives, that much is shared. And how does one calculate loss, particularly a concrete one such as a family member? I can imagine that one feels that loss in the body, like the perpetual pain of a phantom limb. If you leave your homeland, the loss can be as profound as the gain. I think of my aunt, who my father sponsored to Canada in the early 80s. I don’t think she stayed six months, not even two changes of season (maybe it was winter, that would drive anybody away), before returning to Korea. Of course it was because she was in love with a man from her hometown, who she eventually married. But the connection to the homeland can remain forever compelling. Look at all of Canada’s immigrants who return “home” on a regular basis, to the point of buying land with the expectation of retiring there. So where is home, really? In the most positive light, it’s like having two homes, which isn’t a bad deal at all. But of course you need economic flexibility for this. Or, conversely, economic burden—for all the people who make monthly remittances to their parents or relatives—another familiar immigrant duty.

Mike: If shorts mattered in this country (or any other country for that matter) Prey might have become Canada’s Do The Right Thing. Does the marginal status of shorts trouble you, or does it provide more freedom (no one is looking so you can do what you want)?

Helen: Do the Right Thing was a watershed film for its time, a no-holds barred provocation on cultural politics that seemed to define that era. It was extremely influential for a whole generation of indie filmmakers, of colour and not, who felt like they needed to address these issues, if not as head-on as Spike Lee did, at least in a way that was culturally responsible and, moreover, culturally relevant. It was very “new” for its time, very exciting. As for the short film format, I remember attending the Clermont Ferrand Short Film Festival in France with Prey and realizing, hey, shorts are not marginal here in Europe at all, they make them in 35mm and they’re shown before features in theatres and bought for television. Canada and the U.S. have caught up somewhat, but the status of the short filmmaker is still nil. In Europe, you can actually be a short filmmaker forever, and not necessarily have to “graduate” to making feature films—it’s a viable format. But for me, at the time, I didn’t start off making films with the ambition of making features. Shorts were very much my world, having worked at DEC Films in Toronto and Women Make Movies in New York, the arena of non-theatrical film and video for the educational market was/is mainly short films. To me they weren’t marginal at all and I made short films with that attitude. Every frame, every scene and every minute had importance. The fact that it was under 45 minutes and would never show in a film theatre or be known to general audiences, that had no bearing. And then my purview widened some more, as I went beyond my own intellectual and aesthetic pursuits, to realize there’s a whole world out there who didn’t even know what a short film is. I was, maybe, willfully naïve about it.

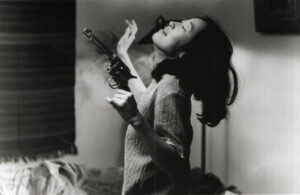

Mike: Subrosa (22 minutes 2000) is a pop-coloured monodrama about a twenty-something orphan, newly landed in Seoul in order to find her mother. This quest narrative ends with little resolution, the city turns into an increasingly blurred and abstract backdrop as she uncovers few clues. Why this story which refuses story telling, these arrested moments shirking any sense of closure?

Helen: I never feel like my films are at all autobiographical but the desperation and futility of the protagonist was something I felt while making Subrosa. The film originated as a kind of prequel for the feature film I was developing at the time, called Priceless (which was never made), which dealt with the same character five years on, still living in Seoul, still engaged in a fruitless search for her mother, among other trials. I’d been enamoured with Korea for a number of years. It’s the place of my birth and, at the time, a country I knew very little about. So of course it had a huge place in my imagination. I think for immigrants there are two contradictory impulses about your home country: one is to negate or ignore it, and the other is to romanticize it and puff it up. I did the latter. I had wanted to make a film in Korea for a number of years, but had a hard time finding the right shape for it–it is indeed a kind of inchoate, all-consuming feeling that you’re trying to hammer out into script form–a difficult task for me. But oddly, the script for Subrosa came out in a couple of days. I was in the throes of a personal crisis, a break-up that I was taking very badly, and the film came out of my wallowing. It was shot in a number of video formats (1-chip and 3-chip mini-DV, Beta SP) then transferred to 35mm film. We shot it over an eight day period and somehow the small five person crew I originally planned ballooned to fifteen–although we were still quick and mobile enough to grab shots in markets, on the streets, by the Han river (there are no filming permits to speak of in Korea). There was enough of a narrative impulse, enough of a kind of story musculature, to permit these “abstractions” as you say. I was aware that the fish-out-of-water and search-for-roots story was familiar enough to take other liberties, and let these scenes slacken into something else. Yes, there was definitely a sense of the closer she got, the further she was, and that her search was less about finding her mother than about losing herself. I think it’s a self-obliteration story.

Mike: The lead is often lensed in extreme close-up, whether taking in her first impressions of the city, talking on the phone, or checking out floral arrangements. The camera proximity centers the action, and grants the viewer an anchor. We are always seeing with her, alongside her. But is the closeness also a kind of deception, because we don’t find out so much about her? Like her lost mother, she is close and far at the same time. We discover little about her in a strict biographical factoid manner, perhaps there is another level of knowing which arrives before that, and which is finally more powerful, and more cinematic?

Helen: Again I wanted our knowledge of this character to be organic, and not psychological. I think you may be detecting a kind of anti-psychological refusal of character, at least in the western sense, where one enunciates oneself all the time about who we are, our tastes, our status, our opinions, our sense of ourselves in every way from what we like to eat, where we went to school, our favourite authors. This is a conception of individualism that is wholly western. We know very little about this Subrosa character. She wears a red coat. She speaks English in an off-accent—although in fact she speaks very little. I think there’s a diaristic feeling to the film. The close-ups you mention are part of an exploration of subjectivity that had been obsessing me for some time. But those decisions also came along with tiny, hand-held cameras which allowed us to fit into tight spaces and produce tight frames. There’s something about seeing someone so large on screen, getting to know an eyelash or a mole; sometimes that says enough about the character because that’s all she’s willing to tell you. The danger, especially dangerous for Asian characters, is to end up being called “inscrutable” because then you’re finished. The viewer doesn’t have an entry point and it’s game over. There’s that fine line between enigmatic and unknowable, a line that many art cinemas graze against, that may be compounded by ethnic or cultural differences that further frustrate or intrigue the viewer, depending on who s/he is. As the main character plunges deeper into an unknown Seoul, she loses herself even more. When she plunges into the river and emerges she arrives at a zero point. As if she’s been born again.

Mike: She is the visitor, the seeker, and is corralled into a bar where she has a nearly wordless sex encounter with the handsome barkeep. You deliver this extimacy in a single, red-tinted medium shot, but I’m wondering if you could elaborate on the question of onscreen sex. It so rarely approaches the boredom and disgust, the rawness and emotional accelerations of “real” sex—is it possible? Pictures have allowed the surrogate experience (as if we were there…) of so many things, does sex lie beyond the image’s capacity?

Helen: She, the main character, is deliberately unnamed. When she asks to see her adoption files, to find out her “real” name, she is denied access. She goes into this search with nothing but her body and her wits, and a small sense of history. The fact that she unwittingly mimics her mother’s past, traveling to the army base town, visiting the brothel for information, and then has passionless sex with a stranger, well it’s more than ironic. I want to cry for her. The red-tinted shot is alluded to early in the film when she checks into a yeogwan (small motel) where she pulls on the overhead light, fluorescent white and then red. All the love motels have it—the red light that’s supposed to be sexy or discreet or something. It’s pretty lurid, that’s for sure. And it’s the same red light under which she has sex. It seemed very appropriate. As for capturing “real sex” on film, I’m not sure what to think of all those ”non-simulated” sex cinema experiments by Catherine Breillat, Leos Carax and the other French filmmakers, or the American one by John Cameron Mitchell (and future blogspots or reality TV cable shows—just the thought itself… I’d rather not), except that you invariably feel a bit like a voyeur. But I know in my films the sex acts are more signifier than signified—it’s about much more than the act itself, and I think most filmmakers would tell you that. But sometimes, like for the aforementioned filmmakers, the act itself is what’s important. I think cinema acts as a kind of “condenser” for all sorts of things, including sex. And the fact that the emotional and physical components, inextricably linked in most forms of sex (even when they are “unemotional” or “empty” experiences—the lack still means something), exceed the limits of cinema’s capture—is that a bad thing? Cinema is many a marvelous thing, and functions from mirror to mimesis to metaphor, but it’s not life. Yes, at times cinema can be realer than life itself, but sometimes woefully not.

Mike: Can you say a few words about Priceless?

Helen: I worked four years on a film that was never made. We garnered continual interest, and attended every selected market from CineMart in Rotterdam to IFFM in New York to IFFCON in San Francisco, to Pusan. Is this in any way sane or normal? No, of course not, it’s potentially self-destructive, to put so much of yourself in a project and have it fail. It’s like starting a small business that goes bankrupt before it even opens. And then there’s the whole psychic, emotional and intellectual investment that seems all for naught. A colossal waste of time and energy. But then you think, hey, maybe it was good practice to write thirty drafts with four different script editors (because, as Toni Morrison says, there’s no such thing as writing, only rewriting) and continually defend its reshaping, even though it still wasn’t good enough in the end. I think there’s an alchemical aspect to filmmaking, outside of logic and reason, akin to karma, that works in your favor and tips you towards a green light, or not. Sometimes it’s your time, and sometimes it’s not. Most people can’t wait it out.

Priceless was a culmination of all the ideas that I had explored in my short films about ethnicity and being an outsider, about cultural displacement and estrangements. But it would be set in a new location for me: Korea, before the plot moves it back to Canada. It was a fish-out-of-water tale, with some thriller/crime elements (starting with an immigration scam that turns into an inadvertent child kidnapping case), but it was an essentially personal story. It’s now five years dead. At the time I thought the funding structure disintegrated and my relationship with producers along with it, but now I realize the opposite is true. Canadian international co-productions with countries other than England or France or Germany (where deals are made in the lingua franca of English) were fairly rare, and the Canadian producers simply felt threatened by the prospect of working hand-in-hand with a Korean production company who didn’t speak their language but would have equal say. This was shortly after the IMF collapse of the Korean economy in 1997, mind you. The irony is that now, with Korean cinema being so hot, it seems like the time is ripe for this kind of film to happen. But back then it was wild, unexplored territory. And, simply put, Canadian producers are a cautious lot, with a lot of tethers choked to the purse strings. It’s the whole oxymoron of the term “independent” which often means dependency on a lot of things, including funding sources tied to deadlines, policies, quotas, etc. It was all together a demoralizing professional experience. When Priceless collapsed, Anita Lee (co-producer on Priceless) approached me about making The Art of Woo. It would be done very quickly, and ultra-low budget.

Mike: Every artist I know makes dazzling things on occasion, and then years might follow which are filled with variations on the same theme, or the minor chords, place holders, the marked time between new ideas or bold expressions. The Art of Woo feels (for me) like one of those movies. How strange that it should be your longest work (not to mention that smooth Dolby sound and 35mm image). The smallest has become the largest: does this seem similarly disproportionate to you?

Helen: Oh god, I just hope it’s not my last. I haven’t made a film in such a long time, I’ve had a burgeoning personal life that I can’t complain about (though I do), relocating to a new country, learning another language (my forgotten mother tongue), taking on responsibilities of motherhood. All the emotional investment and time that I put into films is diverted elsewhere. As for the small/large thing, I don’t regard Woo as either large or small, but one and the same. Because I had that odd view, years ago, that the short film was/is important. It feels so vital at the time, almost like a compulsion, otherwise why would you put up with all the bother and hardship that it takes to cobble together a film? And Woo, despite or probably because of its weaknesses, was truly a learning experience. Sometimes, I agree, you need to “feed” yourself, to simply live life. And then your work takes a different shape, seizes other concerns that reflect this broadening horizon. I can sense this shift happening, because now I live in a completely foreign context from my Canadian upbringing. It’s been a huge adjustment, being in Seoul still makes me feel like an outsider, only with different layers of estrangements and feelings of foreignness. As for what will happen to my filmmaking, yes that would be nice, to think of it as a breather.

Films

Sally’s Beauty Spot 12 minutes 1990

My Niagara 40 minutes 1992

Prey 26 minutes 1995

Subrosa 22 minutes 2000

The Art of Woo 90 minutes 2001